Proquest Dissertations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

La Belle Province: Same Ugly Story

LA BELLE PROVINCE: SAME UGLY STORY A 12-Year Quantitative Analysis of Canada Economic Development for the Regions of Quebec June 2002 News Release -- French English CTF OTTAWA Suite 512 130 Albert Street Ottawa, ON K1P 5G4 Phone: 613-234-6554 Fax: 613-234-7748 Web: www.taxpayer.com ABOUT THE CTF The Canadian Taxpayers Federation (CTF) is a federally incorporated, non-profit, non-partisan, education and advocacy organization founded in Saskatchewan in 1990. It has grown to become Canada’s foremost taxpayer advocacy organization with more than 61,000 supporters nation-wide. The CTF’s three-fold mission statement is: • To act as a watchdog on government spending and to inform taxpayers of governments’ impact on their economic well-being; • To promote responsible fiscal and democratic reforms and to advocate the common interests of taxpayers; and • To mobilize taxpayers to exercise their democratic rights and responsibilities. The CTF maintains a federal and Ontario office in Ottawa and offices in the four provincial capitals of B.C., Alberta, Saskatchewan, and Manitoba. In addition, the CTF recently opened its Centre for Aboriginal Policy Change in Victoria. Provincial offices conduct research and advocacy activities specific to their provinces in addition to acting as regional organizers of Canada-wide initiatives. The CTF’s official publication, The Taxpayer magazine, is published six times a year. CTF offices also send out weekly Let’s Talk Taxes commentaries to over 800 media outlets as well as providing media comment on current events. CTF staff and Board members are prohibited from holding memberships in any political party. -

Guide D'intervention En Matiere De Conservation Et De Mise En Valeur Des Habitats Littoraux D'interet En Basse-Cote-Nord

GUIDE D’INTERVENTION EN MATIÈRE DE CONSERVATION ET DE MISE EN VALEUR DES HABITATS LITTORAUX D’INTÉRÊT SUR LE TERRITOIRE DE LA BASSE-CÔTE-NORD OCTOBRE 2009 P a g e | i GUIDE D’INTERVENTION EN MATIERE DE CONSERVATION ET DE MISE EN VALEUR DES HABITATS LITTORAUX D’INTERET EN BASSE-COTE-NORD OCTOBRE 2009 Introduction P a g e | ii L’ÉQUIPE DE RÉALISATION Recherche et rédaction Mylène Bourque, Comité ZIP Côte-Nord du Golfe Virginie Provost, Comité ZIP Côte-Nord du Golfe Gabriel Mazo, stagiaire, Comité ZIP Côte-Nord du Golfe Révision et validation François Barnard, Ministère des Ressources naturelles et de la Faune (MRNF) Soazig Le Breton, Agence Mamu Innu Kaikusseth (AMIK) Vincent Desormeaux, Ministère du Développement durable, de l’Environnement et des Parcs (MDDEP) Geneviève Pomerleau, Conseil Régional de l’Environnement de la Côte-Nord (CRECN) Virginie Provost, Comité ZIP Côte-Nord du Golfe Sophie Roy, Pêches et Océans Canada (MPO) Hans-Frédéric Ellefsen, Pêches et Océans Canada (MPO) Andrée-Anne Lachance, Centre Aquacole de la Côte-Nord (CACN) Cartographie Mylène Bourque, Comité ZIP Côte-Nord du Golfe Virginie Provost, Comité ZIP Côte-Nord du Golfe Révision linguistique Mylène Bourque et Virginie Provost Conception et impression Imprimerie B&E Partenaires financiers Ce projet est réalisé, en partie, à l’aide d’une contribution du programme Interactions communautaires. Le financement de ce programme conjoint, lié au Plan Saint-Laurent pour un développement durable, est partagé entre Environnement Canada et le ministère du Développement durable, de l’Environnement et des Parcs du Québec. Crédit photos – page de garde : Harrington Harbour, Rorquals à bosse, Iris versicolore et Chevalier grivelé (A. -

Final Report

Final Report - Quebec Lower North Shore- Labrador Straits Regional Collaboration Workshop November 22, 2014 Quebec Lower North Shore-Labrador Straits Final Report Regional Development Workshop List of acronyms ATR: Association touristique régionale CEDEC: Community Economic Development and Employability Corporation CLD: Centre local de éveloppement CRRF: Canadian Rural Revitalization Foundation FFTNL: Fédération des francophones de Terre-Neuve et du Labrador LNS: Lower North Shore MNL: Municipalities Newfoundland and Labrador MUN: Memorial Univeristy ofNewfoundland MRC: Municipalité Régionale de Comté NL: Newfoundland and Labrador OSSC: Organizational Support Services Co-operative QC: Québec QLNS-LS: Québec Lower North Shore-Labrador Straits RED Boards: Regional Economic Development Boards RDÉE TNL: Réseau de développement économique et d’employabilité de Terre-Neuve-et-Labrador UQAR: Université du Québec à Rimouski Page 2 of 42 Quebec Lower North Shore-Labrador Straits Final Report Regional Development Workshop Executive summary The Quebec Lower North Shore-Labrador Straits regional development workshop took place on October 14-16 2014 in Blanc Sablon (Québec) and L’Anse-au-Clair (Newfoundland and Labrador). The objective of this 2-day workshop was to learn from other jurisdictions on cross-boundary collaboration challenges, opportunities, and lessons learned; to assess and identify the local and regional contexts and priorities; and finally to explore and identify potential strategies and actors for moving forward with collaboration -

CULTURES, BORDERS, and BASQUES: ARCHAEOLOGICAL SURVEYS on QUEBEC's LOWER NORTH SHORE William W. Fitzhugh Smithsonian Institution

CULTURES, BORDERS, AND BASQUES: ARCHAEOLOGICAL SURVEYS ON QUEBEC'S LOWER NORTH SHORE William W. Fitzhugh Smithsonian Institution In 1968, soon after returning with slim pickings from my In contrast to Newfoundland, Labrador, and the Straits, first archaeological foray into Lake Melville's boreal for- the archaeology of Quebec's Lower North Shore (LNS), a est, I heard of Jim Tuck's fabulous excavations at Port au region extending 500 km from Sept-Isles to Blanc Choix. It didn't take me long to figure out what Jim had Sablon, is relatively unknown, especially the 300 roadless already discovered - that the archaeological records from kilometers east of Natashquan. This coast was first vis- the interior and the coast were vastly different and that ited by archaeologists in 1928 (Wintemberg 1928, 1942) cultural elaboration and long-term survival in the Subarc- and later was explored by Rene Levesque (Levesque tic required at least seasonal maritime adaptation. In sub- 1962,1968, 1969a, 1969b, 1971, 1972, 1975, 1976, 2002; sequent years Jim went on to excavate stratified sites in Pintal et al. 1985). Published research on the LNS has Saglek, excavated the earliest mound burial in the North- been quite sporadic ( e.g. Martijn 1974; Beaudin et al. east at L'Anse Amour, put Basque whaling at Red Bay 1987; Dumais and Poirier 1994) except in Blanc Sablon and early English settlement at Ferryland on the New and Brador, where D. Chevrier, D. Groisin, and espe- World map, and created at Memorial University one of cially Jean Yves Pintal have worked since the mid-1970s the strongest archaeology programs in North America, (see citations in Pintal 1998). -

Download the Expedition 51 Pdf Guide Here

EXPEDITION 51° A ROAD TRIP THROUGH THE GREAT NORTH! ROUTE 389 AND FERMONT THE TRANS-LABRADOR HIGHWAY (ROUTES 500 AND 510) AND LABRADOR THE CHICOUTAI SCENIC ROAD AND THE LOWER NORTH SHORE _ © Jocelyn Blanchette 2 EXPEDITION 51° EXPEDITION 51° © Patrick Canuel TABLE OF CONTENTS North West River 27 Expedition 51°– An Introduction 4 Labrador Heritage Society Museum 27 Visitor Information Centres 5 Sunday Hill Lookout 27 Full circuit map 6 Labrador Interpretation Centre 27 Battle Harbour 28 Fermont and Route 389 8 Battle Harbour Historic District Information Table 10 28 National Historic Site of Canada Road Conditions 11 Red Bay 28 Driving Rules 11 Red Bay National Historic Site 28 Animals on the Road 11 Right Whale Exhibit Museum 29 Gas Stations 12 Pinware 29 Hospitals 12 Pinware River Provincial Park 29 Washrooms 12 L’Anse-Amour 30 Accommodation and Restaurants 12 L’Anse Amour National Historic Site of Canada 30 Planning your trip 12 Pointe Amour Lighthouse 30 Must-have items 13 L’Anse-au-Clair 31 Other important items 13 Labrador Pioneer Footpath 31 Tourist Attractions on Route 389 14 Hiking Trails 31 Hydroelectric Dams 14 The Chicoutai Scenic Road 32 Manic-2: Jean-Lesage Generating Station 14 and the Lower North Shore Manic-5: Daniel-Johnson Dam 14 Weather 34 Monts Groulx 15 Fermont 16 Gas Stations 34 Accommodation and Restaurants 34 Hiking Trails 16 Internet 34 Northern Lights 17 Cell Phone Service 34 3 Birding 17 Banks 35 Mont-Wright Mine 17 Schefferville, North of Fermont 17 Health Care Services 35 Time Zones 35 The Trans-Labrador Highway -

Manicouagan.Pdf

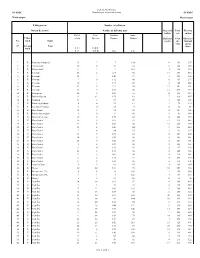

Poll-by-Poll Results/ QUEBEC Résultats par bureau de scrutin QUÉBEC Manicouagan Manicouagan Polling station Number of ballots for - - Bureau de scrutin Nombre de bulletins pour Rejected Total Electors ballots vote on lists Michel Pierre Ghislain André - - - Urban/ Allard Ducasse Fournier Maltais Bulletins Total Électeurs No. rural Name rejetés des figurant - - - votes sur les N° Urbain/ Nom listes rural P.C./ N.D.P./ P.-C. N.P.D. B.Q. Lib. 1 R Kawawachikamach 13 1 7 134 0 155 275 2 R Schefferville 10 6 47 54 5 122 189 3 R Matimekosh 11 2 2 118 1 134 178 4 R Fermont 25 2 214 52 14 307 516 5 R Fermont 38 7 146 39 3 233 356 6 R Fermont 7 0 112 40 6 165 273 7 R Fermont 16 7 114 25 3 165 266 8 R Fermont 32 6 221 66 17 342 521 9 R Fermont 46 7 152 52 13 270 413 10 R Franquelin 20 1 103 55 6 185 287 11 R Rivière-Brochu 31 11 179 82 7 310 455 12 R Godbout 11 2 94 69 4 180 303 13 R Pointe-des-Monts 4 0 53 11 2 70 123 14 R Les Islets-Caribou 3 0 24 9 0 36 51 15 R Baie-Trinité 12 1 94 36 4 147 306 16 R Pointe-aux-Anglais 6 0 31 49 0 86 149 17 R Rivière-Pentecôte 10 3 139 65 5 222 375 18 U Port-Cartier 18 3 161 29 12 223 442 19 U Port-Cartier 47 5 186 66 17 321 499 20 U Port-Cartier 33 4 145 64 9 255 440 21 U Port-Cartier 7 4 84 25 2 122 237 22 U Port-Cartier 18 5 198 62 6 289 500 23 U Port-Cartier 14 6 156 68 5 249 431 24 U Port-Cartier 24 9 160 69 2 264 391 25 U Port-Cartier 8 4 129 36 8 185 358 26 U Port-Cartier 11 0 119 39 8 177 328 27 U Port-Cartier 25 5 154 36 5 225 366 28 U Port-Cartier 21 3 102 90 4 220 361 29 U Port-Cartier 11 2 114 71 5 -

Travelling for Health? Toolkit

TRAVELLING FOR HEALTH? TOOLKIT LOWER NORTH SHORE USEFUL INFORMATION FOR PEOPLE WHO HAVE TO TRAVEL OUT-OF-REGION TO ACCESS HEALTH SERVICES The goal for this TOOLKIT is to provide English-speakers with helpful information when they must travel out‐of‐region for health services. A Steering Committee oversaw the development of this project with support from the Committee for Anglophone Social Action (CASA) and Jeffrey Hale Community Partners (JHCP). The information provided focuses on services available locally, as well as services in places where patients may be sent for specialized services. The Project’s Steering Committee judged that this information might be helpful to anyone needing to travel out-of-region and decided to offer the TOOLKIT in both English and French. We hope you find this TOOLKIT useful! This initiative is funded by the CHSSN and Health Canada through the Roadmap for Canada’s Official Languages 2013-2018: Education, Immigration, Communitie The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent the views of Health Canada. Table of contents About Travel4Health 1 Mission 1 How this guide was developed 1 Preparing for your trip 2 What it means to travel outside your region for health 2 What to expect 2 Unexpected situations 3 Packing lists 3 Checklists 5 Bringing a support person 5 Leaving your home in good hands 6 Leaving from: Lower North Shore 8 Transportation support 8 Financial Support offered locally 9 CLSC services 9 Going to: North Shore (Sept-Îles & Baie-Comeau) 11 Sept-Îles Hospital 13 CISSS de la Côte-Nord 14