NT Government

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

OPENING STATEMENT FULL VERSION 1. Introduction Thank You

OPENING STATEMENT FULL VERSION 1. Introduction Thank you Chair and Committee for providing Glencore with an opportunity to speak today. We have a full opening statement that can be read into Hansard but would like to highlight a number of key points for the Committee on our business model, tax payments and corporate structures. 2. Glencore Business Model Glencore is one of the world’s largest, diversified natural resource companies, an integrated global producer and marketer of bulk commodities. Our commodities include metals and minerals, energy products and agricultural products. We have more than 90 marketing offices in over 50 countries and our global portfolio of industrial assets includes over 150 mining and metallurgical, oil production and agricultural facilities. We market and distribute physical commodities sourced from our own production and also from third party producers. We also provide financing, processing, storage, logistics and other services to both producers and consumers of commodities. Our global marketing business is a major point of differentiation from our mining peers. Glencore’s direct and indirect business interests span the entire supply chain from exploration and production through to smelting, refining, storage and handling, packaging, rail, trucking, shipping, marketing and trading through to customer end use. Our marketing business is a global logistics network, supplying the commodities that are needed to the places that need them most, sustainably and responsibly. We are open and transparent about our business, and value the relationships we have with our stakeholders. We are proud to be a member of the International Council on Mining and Metals (ICMM), a supporter of the Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative (EITI) and we recently joined the plenary of the UN Voluntary Principles on Security and Human Rights. -

Anastasia Bauer the Use of Signing Space in a Shared Signing Language of Australia Sign Language Typology 5

Anastasia Bauer The Use of Signing Space in a Shared Signing Language of Australia Sign Language Typology 5 Editors Marie Coppola Onno Crasborn Ulrike Zeshan Editorial board Sam Lutalo-Kiingi Irit Meir Ronice Müller de Quadros Roland Pfau Adam Schembri Gladys Tang Erin Wilkinson Jun Hui Yang De Gruyter Mouton · Ishara Press The Use of Signing Space in a Shared Sign Language of Australia by Anastasia Bauer De Gruyter Mouton · Ishara Press ISBN 978-1-61451-733-7 e-ISBN 978-1-61451-547-0 ISSN 2192-5186 e-ISSN 2192-5194 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data A CIP catalog record for this book has been applied for at the Library of Congress. Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data are available on the Internet at http://dnb.dnb.de. ” 2014 Walter de Gruyter, Inc., Boston/Berlin and Ishara Press, Lancaster, United Kingdom Printing and binding: CPI books GmbH, Leck Țȍ Printed on acid-free paper Printed in Germany www.degruyter.com Acknowledgements This book is the revised and edited version of my doctoral dissertation that I defended at the Faculty of Arts and Humanities of the University of Cologne, Germany in January 2013. It is the result of many experiences I have encoun- tered from dozens of remarkable individuals who I wish to acknowledge. First of all, this study would have been simply impossible without its partici- pants. The data that form the basis of this book I owe entirely to my Yolngu family who taught me with patience and care about this wonderful Yolngu language. -

STRATEGIC PLAN 2016 – 2019 Contents

TOURISM CENTRAL AUSTRALIA STRATEGIC PLAN 2016 – 2019 Contents Introduction from the Chair ..........................................................................3 Our Mission ........................................................................................................4 Our Vision ............................................................................................................4 Our Objectives ...................................................................................................4 Key Challenges ...................................................................................................4 Background .........................................................................................................4 The Facts ..............................................................................................................6 Our Organisation ..............................................................................................8 Our Strengths and Weaknesses ...................................................................8 Our Aspirations ................................................................................................10 Tourism Central Australia - Strategic Focus Areas ...............................11 Improving Visitor Services and Conversion Opportunities ...............11 Strengthening Governance and Planning ..............................................12 Enhancing Membership Services ..............................................................13 Partnering in Product -

Annual Report 2017/18

East Arnhem Regional Council ANNUAL REPORT 2017/18 01. Introduction President’s Welcome 6 02. East Arnhem Profile Location 12 Demographics 15 National & NT Average Comparison 17 Wards 23 03. Organisation CEO’s Message 34 Our Vision 37 Our Mission 38 Our Values 39 East Arnhem Regional Council 40 Executive Team 42 04. Statutory Reporting Goal 1: Governance 48 Angurugu 52 Umbakumba 54 Goal 2: Organisation 55 Milyakburra 58 Ramingining 60 Milingimbi 62 Goal 3: Built & Natural Environment 63 Galiwin’ku 67 Yirrkala 70 Gunyangara 72 Goal 4: Community & Economy 73 Gapuwiyak 78 05. Council Council Meetings Attendance 88 Finance Committee 90 WARNING: Aboriginal & Torres Strait Islander people should be aware that this publication may contain images Audit Committee 92 and names of people who have since passed away. Council Committees, Working Groups & Representatives 94 Elected Member Allowances 96 2 East Arnhem Regional Council | Annual Report 2017/2018 East Arnhem Regional Council | Annual Report 2017/2018 3 INTRODUCTION 4 East Arnhem Regional Council | Annual Report 2017/2018 East Arnhem Regional Council | Annual Report 2017/2018 5 Presidents Welcome On behalf of my fellow Council Members, I am pleased to In February 2018 our Local Authorities were spilled and new opportunities desperately needed. It is also important that I working together, to support and strengthen our people and present to you the East Arnhem Regional Council 2017 - 2018 nominations called. I’d like to acknowledge the outgoing Local recognise and thank the staff of the Department of Housing opportunities. Acting Chief Executive Officer Barry Bonthuys Annual Report, the tenth developed by Council. -

Northern Territory Government Response to the Joint Standing Committee on Migration – Inquiry Into Migrant Settlement Outcomes

Northern Territory Government Response to the Joint Standing Committee on Migration – Inquiry into Migrant Settlement outcomes. Introduction: The Northern Territory Government is responding to an invitation from the Joint Standing Committee on Migration’s inquiry into migrant settlement outcomes. The Northern Territory Government agencies will continue to support migrants, including humanitarian entrants through health, education, housing and interpreting and translating services and programs. The Northern Territory Government acknowledges the important role all migrants play in our society and recognises the benefits of effective programs and services for enhanced settlement outcomes. The following information provides details on these programs that support the settlement of the Northern Territory’s migrant community. 1. Northern Territory Government support programs for Humanitarian Entrants Department of Health The Northern Territory Primary Health Network was funded by the Department of Health to undertake a review of the Refugee Health Program in the Northern Territory. The review informed strategic planning and development of the Refugee Health Program in the Northern Territory prior to the development of a tender for provision of these services. The primary objectives of the Program were to ensure: increased value for money; culturally safe and appropriate services; greater coordination across all refugee service providers; clinically sound services; improved health literacy for refugees; and flexibility around ebbs and flows -

FPA Legislation Committee Tabled Docu~Ent No. \

FPA Legislation Committee Tabled Docu~ent No. \, By: Mr~ C'-tn~:S AOlSC, Date: b IV\a,c<J..-. J,od.D , e,. t\-40.M I ---------- - ~ -- Australian Government National IndigeJrums Australlfans Agency OFFICIAL Chief Executive Officer Ray Griggs AO, CSC Reference: EC20~000257 Senator Tim Ayres Labor Senator for New South Wales Deputy Chair, Senate Finance and Public Administration Committee 6 March 2020 Re: Additional Estimates 2019-2020 Dear Senatafyres ~l Thank you for your letter dated 25 February 2020 requesting information about Indigenous Advancement Strategy (IAS) and Aboriginals Benefit Account (ABA) grants and unsuccessful applications for the periods 1 January- 30 June 2019 and 1 July 2019 (Agency establishment) - 25 February 2020. The National Indigenous Australians Agency has prepared the attached information; due to reporting cycles, we have provided the requested information for the period 1 January 2019 - 31 January 2020. However we can provide the information for the additional period if required. As requested, assessment scores are provided for the merit-based grant rounds: NAIDOC and ABA. Assessment scores for NAIDOC and ABA are not comparable, as NAIDOC is scored out of 20 and ABA is scored out of 15. Please note as there were no NAIDOC or ABA grants/ unsuccessful applications between 1 July 2019 and 31 January 2020, Attachments Band D do not include assessment scores. Please also note the physical location of unsuccessful applicants has been included, while the service delivery locations is provided for funded grants. In relation to ABA grants, we have included the then Department's recommendations to the Minister, as requested. -

KUNINJKU PEOPLE, BUFFALO, and CONSERVATION in ARNHEM LAND: ‘IT’S a CONTRADICTION THAT FRUSTRATES US’ Jon Altman

3 KUNINJKU PEOPLE, BUFFALO, AND CONSERVATION IN ARNHEM LAND: ‘IT’S A CONTRADICTION THAT FRUSTRATES US’ Jon Altman On Tuesday 20 May 2014 I was escorting two philanthropists to rock art galleries at Dukaladjarranj on the edge of the Arnhem Land escarpment. I was there in a corporate capacity, as a direc- tor of the Karrkad-Kanjdji Trust, seeking to raise funds to assist the Djelk and Warddeken Indigenous Protected Areas (IPAs) in their work tackling the conservation challenges of maintain- ing the environmental and cultural values of 20,000 square kilometres of western Arnhem Land. We were flying low in a Robinson R44 helicopter over the Tomkinson River flood plains – Bulkay – wetlands renowned for their biodiversity. The experienced pilot, nicknamed ‘Batman’, flew very low, pointing out to my guests herds of wild buffalo and their highly visible criss-cross tracks etched in the landscape. He remarked over the intercom: ‘This is supposed to be an IPA but those feral buffalo are trashing this country, they should be eliminated, shot out like up at Warddeken’. His remarks were hardly helpful to me, but he had a point that I could not easily challenge mid-air; buffalo damage in an iconic wetland within an IPA looked bad. Later I tried to explain to the guests in a quieter setting that this was precisely why the Djelk Rangers needed the extra philanthropic support that the Karrkad-Kanjdji Trust was seeking to raise. * * * 3093 Unstable Relations.indd 54 5/10/2016 5:40 PM Kuninjku People, Buffalo, and Conservation in Arnhem Land This opening vignette highlights a contradiction that I want to explore from a variety of perspectives in this chapter – abundant populations of environmentally destructive wild buffalo roam widely in an Indigenous Protected Area (IPA) declared for its natural and cultural values of global significance, according to International Union for the Conservation of Nature criteria. -

Report on the Administration of the Northern Territory for the Year 1939

1940-41 THE PARLIAMENT OF THE COMMONWEALTH OF AUSTRALIA. REPORT ON THE ADMINISTRATION OK THE NORTHERN TERRITORY FOR YEAR 1939-40. Presented by Command, 19th March, 1941 ; ordered to be printed, 3rd April, 1941. [Cost of Paper.—Preparation, not given ; 730 copies ; approximate coat of printing and publishing, £32.) Printed and Published for the GOVERNMENT of the COMMONWEALTH OF AUSTRALIA by L. F. JOHNSTON, Commonwealth Government Printer. Canberra. (Printed In Australia.) 3 No. 24.—F.7551.—PRICE 1S. 3D. Digitised by AIATSIS Library 2007 - www.aiatsis.gov.au 17 The following is an analysis of the year's transactions :— £ s. d. Value of estates current 30th June, 1939 .. 3,044 0 5 Receipts as per cash book from 1st July, 1939 to 30th June, 1940 3,614 1 3 Interest on Commonwealth Savings Bank Accounts 40 9 9 6,698 11 5 Disbursements from 1st July, 1939, to 30th June, 1940 £ s. d. Duty, fees and postage 98 3 5 Unclaimed estates paid to Revenue 296 3 8 Claims paid to creditors of Estates 1,076 7 2 Amounts paid to beneficiaries 230 18 4 1,701 12 7 Values of estates current 30th June, 1940 4,996 18 10 Assets as at 30th June, 1940 :— Commonwealth Bank Balance 1,741 9 7 Commonwealth Savings Bank Accounts 3,255 9 3 4,996 18 10 PATROL SERVICE. Both the patrol vessels Kuru amd Larrakia have carried out patrols during the year and very little mechanical trouble was experienced with either of them. Kuru has fulfilled the early promise of useful service by steaming 10,000 miles on her various duties, frequently under most adverse weather conditions. -

Central Australia Regional Plan 2010-2012 2012 - 2010

Department of Health and Families Central Australia Regional Plan 2010-2012 2012 - 2010 www.healthyterritory.nt.gov.au Northern Territory Central Region DARWIN NHULUNBUY KATHERINE TENNANT CREEK Central Australia ALICE SPRINGS 3 Central Australia Regional Plan In 2009, former Chief Executive of the Department of Health and Families (DHF), Dr David Ashbridge, launched the Department of Health and Families Corporate Plan 2009–2012. He presented the Corporate Plan to Department staff, key Government and political representatives, associated non-government organisations, Aboriginal Medical Services and peak bodies. The Central Australia Regional Plan is informed by the Corporate Plan and has brought together program activities that reflect the Department’s services that are provided in the region, and expected outcomes from these activities. Thanks go to the local staff for their input and support in developing this Plan. 4 Central Australia Regional Overview In the very heart of the nation is the Central Australia Region, covering some 830,000 square kilometres. Encompassing the Simpson and Tanami Deserts and Barkly Tablelands, Central Australia shares borders with South Australia, Queensland and Western Australia. The Central Australia Region has a population of 46,315, of which 44 per cent identify as Indigenous Australians (2007). 1 Approximately 32,600 people live in the three largest centres of Alice Springs (28,000), Tennant Creek (3,000) and Yulara (1,600). The remainder of the population reside in the 45 remote communities and out-stations. Territory 2030, the Northern Territory Government’s plan for the future, identifies 20 Growth Towns, five of which are in Central Australia – Elliott, Ali Curung, Yuendumu, Ntaria (Hermannsburg) and Papunya. -

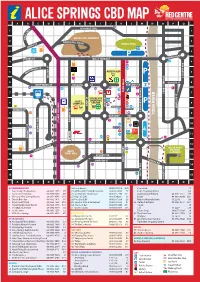

Alice Springs Cbd Map a B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q 14 Schwarz Cres 1 Es 1 R C E

ALICE SPRINGS CBD MAP A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q 14 SCHWARZ CRES 1 ES 1 R C E L E ANZAC HILL LOOKOUT H 2 ZAC H 2 AN ILL ROAD ST ANZAC OVAL TH SMI 3 P 3 UNDOOLYA RD STOKES ST WILLS TERRACE 4 8 22 4 12 LD ST 28 ONA 5 CD ALICE PLAZA 5 M P 32 LINSDAY AVE LINSDAY COLSON ST COLSON 4 6 GOYDER ST 6 WHITTAKER ST PARSONS ST PARSONS ST 43 25 20 21 9 1 29 TODD TODD MALL 7 38 STURT TERRACE 7 11 2 YEPERENYE 16 COLES SHOPPING 36 8 CENTRE 48 P 8 COMPLEX 15 BATH ST BATH 33 HARTLEY ST REG HARRIS LN 45 27 MUELLER ST KIDMAN ST 23 FAN ARCADE LEICHARDT TERRACE LEICHARDT 9 37 35 10 9 GREGORY TCE RIVER TODD 7 RAILWAY TCE RAILWAY 10 HIGHWAY STUART 10 24 41 46 P 47 GEORGE CRES GEORGE 44 WAY ONE 11 32 11 26 40 TOWN COUNCIL FOGARTY ST LAWNS 3 5 34 12 STOTT TCE 12 42 OLIVE PARK LARAPINTA DRV BOTANIC BILLY 39 31 GARDENS 13 GOAT HILL 13 6 13 STUART TCE 18 TUNCKS RD SIMPSON ST STREET TODD 14 19 14 17 49 15 SOUTH TCE 15 BARRETT DRV A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q ACCOMMODATION 24. Loco Burrito 08 8953 0518 K10 Centrelink F5 1. Alice Lodge Backpackers 08 8953 1975 P7 25. McDonald’s Family Restaurant 08 8952 4555 E7 Coles Shopping Centre G8 2. -

Hillgrove Resources Limited

ASIA PACIFIC COPPER MINER INVESTOR PRESENTATION MARCH 2011 DISCLAIMER No representation or warranty is or will be made by any person (including Hillgrove Resources Limited ACN 004 297 116 (Hillgrove) and its officers, directors, employees, advisers and agents) in relation to the accuracy or completeness of all or part of this document (the Presentation), or the accuracy, likelihood of achievement or reasonableness of any forecasts, prospects or returns contained in, or implied by, the Presentation or any part of it. The Presentation includes information derived from third party sources that has not been independently verified. The Presentation contains certain forward-looking statements with respect to the financial condition, results of operations and business of Hillgrove and certain plans and objectives of the management of Hillgrove. Forward-looking statements can generally be identified by the use of words such as ‘project’, ‘foresee’, ‘plan’, ‘expect’, ‘aim’, ‘intend’, ‘anticipate’, ‘believe’, ‘estimate’, ‘may’, ‘should’, ‘will’ or similar expressions. Indications of, and guidance on, production targets, targeted export output, expansion and mine development timelines, infrastructure alternatives and financial position and performance are also forward-looking statements. Any forecast or other forward-looking statement contained in the Presentation involves known and unknown risks and uncertainties and may involve significant elements of subjective judgment and assumptions as to future events which may or may not be correct. Such forward-looking statements are not guarantees of future performance and involve known and unknown risks, uncertainties and other factors, many of which are beyond the control of Hillgrove, and may cause actual results to differ materially from those expressed or implied in such statements. -

Newsletter # 142 January 2019

RSL ANGELES CITY SUB BRANCH PHILIPPINES Issue 142 RSL Angeles City Sub Branch Philippines NEWSLETTER # 142 JANUARY 2019 WEBSITE: WWW.RSLANGELESCITY.COM FACEBOOK: WWW.FACEBOOK.COM/RSLACITY HAPPY AUSTRALIA DAY 2019 RSL ANGELES CITY SUB BRANCH PHILIPPINES Issue 142 Angeles City and commence the construction and issue to a considerable back log of President’s Report children on the waiting list. By: Gary Barnes – Sub-Branch President After due consideration, the Committee has now selected the builder for the construction of the new clubrooms and wheelchair storage January 2019 and assembly facility. He is currently in discussion with the owners of the Fenton Hi to all our members and anyone else Hotel to ascertain a suitable commencement around the world that takes the time to read date. Avenues of external funding for this our monthly facility are currently being vigorously pursued newsletter. I by the Committee, however, this will not hope you all delay the construction in any way. had a very Merry Xmas Australia Day 2019 - The Australia Day and on behalf function for all members and their families of the will be held on Sat 26th Jan, at the Fenson Committee, I Hotel. Check out all the details in the flyer wish you all a within this newsletter. Please note that as the prosperous Fenson Hotel has an un-fenced swimming and Happy New Year. pool, we have arranged for a qualified Lifeguard to be in attendance for the duration There was no Medical Mission conducted of the function. in Jan, with the next one scheduled for 2 Feb 2019.