Royapettah Scoring System" - a Functional Assessment of Oral Cancer Resection

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gtgl.L+,I Ggooruunuf, '

I +rl gtgl.l+,i GluEEri, $tU. p. ggrgrlonir., @.gg.u, @ru&qpri, ggooruunuf, C-ir$l r-o&ooh 6lpnufq$ gJ6Dp, egne pafi upg6 opgtcomal Sttp gmp, pcooon-o& Glsruoori ' urutorir^mnaflnno, anepmiGr:Leou, 6locirooeur - 9 Gleoirnnan - 15. p.o.erobr 10680/ uLfl-1(42020 prsir. 16.09.2020 Elu1r, 6lun6sh egrc palb upg1h spglffurqp Slit- ggroruuru:ryerb Widlp gcooo.rf crrb.gfl.ggri spgl6nrolp $I-urb Gleoiraoan r-onorlurb epgJ6uurq g4oor.orir.rerniooir, s6Dr-0ru6ir rJpgtrir s6urr0uJ6b o-pofluneinieoh srer5hl uorrfluluriroeir Frnqpeil Glprufuro graflp$oofkir u$$lflcoo Glefi$l Glotafl u9u& Gongpar -urbu$pr-ono. umiroor J{[trr6u,6rur (6leoar) naiur 163 ogro panir upEtri epglcuurq Sl..p (es-8-4 gJW pnoir 18.08.2010 Glu<DEory Gls6iT6iDdn r.onporynr-dld;gr-uir- uehafle$gruinol ror.oruraroaflil 6IEuL6l6h6r epg1cuurq g4rororiunodseir, s6nr0lua:f rafErir s6unnud o-pofluncmiooir uoufluJtr-dtsroen Gprg prur.ocmrir grourir S'ip6l Glofiqt Glun6r-@ $tpgLrin @eoeuur6euuur- gp!&eooufleoar Gleoireoan uptq proflp$oafleir u$$lrfld;coo Glefi$Iuno Gloraflu9r- p&a pr-orySroo Gr-ofGloroirqgr-orE gldirqLrir Gor-@i GlonoirdlGpoir. g6/-p.ggr9rromi sgD6 Fn gSancumruf @ronurriq 1. eFgeuurq g4eor.oriurenlq&onnn gqdbr5Broo upOJ6 o5leuurounlu ugor6(2) 2. erororun:folqgBonnn g4pffid;roo rofErir oflerurruurrlu ugarb(4 3. edoolu5t o-gaflu.rnenlq&ornn gdleifl&nno u$Ern ofleuurarunlu ugnli (Q llggneailtugll " {' E(95 Fap Etmp, Gllccircoour r.onorir-dr g4pfl oflBeoo 1N otifi cati o n ) eggl6uurq gqorr-oriunerni, eromurzuri rrpEjrir e6DL0ru6iJ o-gailunoni onnSh]ruoufluSl--r,ioeir Gpng $luLroandr grzu6$lnuqargl p.o.nafrr. 10680/ es-6t-1(42020 pnoir 16.09.2020 " Glooircnan mnor-r-$$lrir d$ $lurag6 qrlt-Clp pronroLf *i,.dl.gU'i o$g1eurna{$ SlLu ueirerfl spglruwq cororunioofleir opur-@rircn spgt6r6ro1 g4cor,oriunomi, ecouruzuri ropg1t efiDL0r!6t e-po9lunerni enafluuouflu9r-rarooir Gprg pulaonb grorb prrur5[- Gluarur o9larurarurriupffiooflur.6lg$g r-or-@dl afleuurerorrlunroeh ornGzuf oiu@6loirpco. -

Manali Petrochemicals Limited

Manali Petrochemicals Limited SPIC House, 88, Mount Road, Guindy, Chennai - 600 032 Telefax : 044 - 2235 1098 Website : www.manalipetro.com CIN : L24294TN1986PLC013087 ' Ref: MPL J Sectl I BSE & NSE I E-2 & E-3 I 2018 z'" August 2018 The Manager, The Listing Department Listing Department, National Stock Exchange of India BSE Limited Limited Corporate Relationship Exchange Plaza, s" Floor, Department Plot No .C/11 G Block, 1st Floor, New Trading Ring, Bandra-Kurla Complex, Rotunda Building, P J Tower, Bandra (East) Dalal Street, Fort, Mumbai - 400 051 Mumbai - ~oo 001. Stock Code: MANALIPETC Stock Code: 500268 Dear Sir, Sub: Submission of Annual Report for the year 2017-18 - reg. Pursuant to Regulation 34 of the SEBI (LODR) Regulations, 20151 we submit herewith the Annual Report for the year 2017-18 in pdf version We request you to kindly take above on record. Thanking you, Yours faithfully, For Manali Petrochemicals Limited R Kothandaraman Company Secretary Encl.: As above ISO 9001 REGISTERED ISO 14001 REGISTERED Factories: Plant - 1 : Ponneri High Road, Manali, Chennai - 600 068 (IQ Plant - 2 : Sathangadu Village, Manali, Chennai - 600 068 (IQ ~ MGMlSYS. ~ MGMlSYS. ~ RvACOL4 Phone : 044 - 2594 1025 Fax : 044 - 2594 1199 ~ RvACOt4 ONV Certification B.V., The Netherlands DNV Certification B.V.. The Netherlands E-mail: [email protected] ANNUAL REPORT 2017 - 18 Manali Petrochemicals Limited Board of Directors Auditors Ashwin C Muthiah DIN: 00255679 Chairman Brahmayya & Co. Brig (Retd.) Harish Chandra Chawla DIN: 00085415 Director Chartered -

Tamil Nadu Government Gazette

© [Regd. No. TN/CCN/467/2012-14. GOVERNMENT OF TAMIL NADU [R. Dis. No. 197/2009. 2013 [Price: Rs. 26.40 Paise. TAMIL NADU GOVERNMENT GAZETTE PUBLISHED BY AUTHORITY No. 16] CHENNAI, WEDNESDAY, APRIL 24, 2013 Chithirai 11, Vijaya, Thiruvalluvar Aandu–2044 Part VI—Section 4 Advertisements by private individuals and private institutions CONTENTS PRIVATE ADVERTISEMENTS Pages Change of Names .. 925-990 NOTICE NO LEGAL RESPONSIBILITY IS ACCEPTED FOR THE PUBLICATION OF ADVERTISEMENTS REGARDING CHANGE OF NAME IN THE TAMIL NADU GOVERNMENT GAZETTE. PERSONS NOTIFYING THE CHANGES WILL REMAIN SOLELY RESPONSIBLE FOR THE LEGAL CONSEQUENCES AND ALSO FOR ANY OTHER MISREPRESENTATION, ETC. (By Order) Director of Stationery and Printing. CHANGE OF NAMES 14035. I, S. Sulaihal Beevi, wife of Thiru J. Shaik Maideen, 14038. I, S. Vinod Venkatesh, son of Thiru D. Subas Bose, born on 20th March 1975 (native district: Sivagangai), residing born on 12th October 1975 (native district: Madurai), residing at No. 400-M, Sethurani, Ilayangudi, Sivagangai-620 702, at Old No. 125, New No. 236, South Veli Street, Madurai-625 001, shall henceforth be known shall henceforth be known as S. MEHARAJ BEGAM. as VINOD VENKATESH BOSE. S. SULAIHAL BEEVI. S. VINOD VENKATESH. Sivagangai, 15th April 2013. Madurai, 15th April 2013. 14036. I, J. Kharathikayanee, wife of Thiru G. Nataraj, born 14039. I, R. Syed Abdul Razak, son of Thiru K. Abdul Rasheed, on 27th May 1981 (native district: Coimbatore), residing at born on 9th March 1961 (native district: Dindigul), residing No. 5, Lakshmipuram, Ganapathy, Coimbatore-641 006, at No. 1/685, R R Nagar, Karur Road, Seelapadi, Dindigul- shall henceforth be known as J. -

ARMB, No – 27, Ground Floor, Arul Manai, Whites Road, Royapettah, Chennai, Tamil Nadu - 600014

ARMB, No – 27, Ground Floor, Arul Manai, Whites Road, Royapettah, Chennai, Tamil Nadu - 600014 TERMS AND CONDITIONS OF SALE OF IMMOVABLE/MOVABLE SECURED ASSETS 1. Name and address of the Borrower/ Co - 1. M/S Aran Kitchen World India Private limited, obligant/Guarantor (Borrower) New no 105 (54), Chamiers road, Raja Annamlaipuram, Chennai – 600 028 2. (A) Mr. Rajesh Jain Bohra Son of Late Motilal Jain 2nd Floor, New no 105, Chamiers road Raja Annamalaipuram, Chennai – 600 028 2. (B) Mr. Ashok Jain Bohra Son of Late Motilal Jain Flat no 5-B/5, 21/5 Warran road Abhiramapuram, Mylapore Chennai – 600 004 2. (C) M/S Bohra Kitchens Pvt Ltd, (Guarantor) No 105, Chamiers road Raja Annmalaipuuram Chennai – 600 028 2. (D) M/S Bohra Sanitaries Pvt Ltd, (Guarantor) No 105, Chamiers road Raja Annmalaipuuram Chennai – 600 028 2. Name and address of the Secured Creditor : Union Bank of India (E CORPORATION BANK) Chennai – ARM Branch, “Arul Manai” Building, No.27, Whites Road, Chennai – 600 014 Phone: 044-28545446 / 9567761988 3. Description of immovable / movable secured assets to be Sold: 1.Item No.1: All that piece and parcel of Commercial flat in basement and ground floors of the building, with UDS in land of 1714 sqft out of 6993 sqft, located on Plot No .7, Old Door No 54, New Door no 105, Chamiers Road, Raja Annamalaipuram, Chennai 600 028, situated in R.S.No.3925/2, R.S.No.3925/41 of Mylapore Village, Mylapore – Triplicane Taluk, Chennai District, within the Sub Registration District of Mylapore & Registration District of Chennai Central, in the name of M/S Bohra Sanitaries Pvt Ltd. -

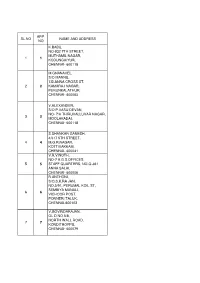

Sl.No App. No Name and Address 1 1 K.Babu, No-932

APP. SL.NO NAME AND ADDRESS NO K.BABU, NO-932 7TH STREET, MUTHAMIL NAGAR, 1 1 KODUNGAIYUR, CHENNAI- 600118 M.GNANAVEL, S/O MANNU, 7.B.ANNA CROSS ST, 2 2 KAMARAJ NAGAR, PERUNKALATHUR, CHENNAI- 600063 V.ALEXANDER, S/O P.VASU DEVAN, NO- 7/A THIRUVALLUVAR NAGAR, 3 3 MOOLAKADAI, CHENNAI- 600118 S.SHANKAR GANESH, 4/317 5TH STREET, 4 4 M.G.R.NAGAR, KOTTIVAKKAM, CHENNAI- 600041 V.R.VINOTH, NO-7 A.G.S.OFFICES, 5 5 STAFF QUARTERS, NO-Q-361 ANNA SALAI, CHENNAI- 600006 R.ANTHONI, S/O.S.K.RA JAN, NO.5/91, PERUMAL KOIL ST, SEMBIYA MANALI, 6 6 VICHOOR POST, PONNERI TALUK, CHENNAI-600103 V.GOVINDARAJAN, OL D NO.5/8, NORTH WALL ROAD, 7 7 KONDITHOPPU, CHENNAI- 600079 G.SIVAKUMAR, NO- 39/12 GANGAIAMMAN KOIL ST, 8 8 LAKSHMIPURAM, THIRUVANMIYUR CHENNAI- 600041 D.MOHAN, N0.22,KARUNANITHI ST, 9 9 KODUNGAYUR, CHENNAI- 600118 G.KARTHIKEYAN, 56,III RD BLOCK, HOUSING BOARD, 10 10 SATHYAMURTY NAGAR, VYASARPADI, CHENNAI-600039 C.SRINIVASAN, 1, 88TH SETREET, 11 11 ASHOK NAGAR, CHENNAI-600083 S,SIVASUBRAMANI, NO.137,5-BLOCK, 4THFLOOR, 12 12 HOUSING BOARD, PERIYAR NAGAR, PULIANTHOPE, CHENNAI- 600012 N.SATHISH, 13 13 NO.27, RADAS NAGAR, CHENNAI- 600021 D.SHANMUGAM, 69/37, ANGALAMMAN KOIL ST, 14 14 GOVINDAPURAM, CHENNAI- 600012 V. MUNIRAJ, 59, SOLAIAMMAN ST,, KODUNGAIYUR, 15 15 CHENNAI- 600118 C.KARNAN, N.NO.24,ARULAYAMMANPET, 16 16 GUINDY CHENNAI-600032 K.KARTHICK, NO.9,PER IYA PALAYATHAMAN KOIL , 17 17 7TH ST, MOOLAKOTHALAM, CHENNAI- 600021 DILLIBABU M, NO.5, ELUMALAI ST, 18 18 SAIDAPET, CHENNAI- 600015 R.MURUGAN, NEW NO.172,OLD NO.203, DOSS NAGAR, 19 19 5TH STREET, -

The New College Chennai

CENTRE FOR ACADEMIC LEADERSHIP AND EDUCATION MANAGEMENT ( CALEM ) Under the Scheme of Pandit Madan Mohan Malaviya National Mission on Teachers and Teaching ( PMMMNMTT ) MHRD, Govt. Of India List of Participants Short Term Course on Academic Leadership From 09-02-2017 to 15-02-2017 Course Director : Professor A.R. Kidwai, Director, UGC HRDC, AMU, Aligarh Course Assistant Director : Dr. Faiza Abbasi, Assistant Professor, UGC HRDC, AMU, Aligarh Course Coordinator : Dr. Major Zahid Husain, Principal, The New College, Chennai (TN) Venue : The New College, Chennai (TN) S. Name & Designation Subject Institutional Address Residential Address M/F No. SC/ST OBC/M 1. Mr. H. Abdul Hadi English The New College No.39/18, II Floor, M/M Assistant Professor Chennai (TN) Khanabagh Street, Triplicane, Chennai – 5. Mr. Y.A. Zaheer Abdul English The New College No. 34, Gurusamy Street, M/M 2. Ghafoor Chennai (TN) Sembium Perambur, Assistant Professor Chennai – 11. Mr. B. Mohamed Hussain English The New College No.3, Manali Saravana M/M 3. Ahamed Chennai (TN) Nagar, Mangadu, Assistant Professor Chennai -122. Mr. A. Mohammed English The New College No.73/2A, Paper Mills M/M 4. Farhatullah Chennai (TN) Road, Sembium, Assistant Professor Perambur, Chennai – 11. Mr. F. Mohideen Basha Tamil The New College No.77, D.B.K. Street, M/M 5. Assistant Professor Chennai (TN) Old Washermenpet, Chennai – 21. Dr. Syed Kamalullah Arabic The New College #21/4, Yahya Ali , M/M 6. Bakhtiary Chennai (TN) IInd Street, Teynampet, Assistant Professor Chennai – 6. Dr. K. Mujeeb Rahman Arabic The New College New No.14, Old No.42/1, M/M 7. -

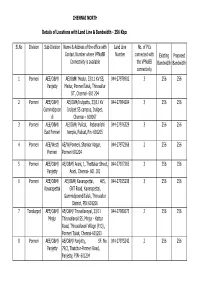

CHENNAI NORTH Sl.No Division Sub-Division Name & Address Of

CHENNAI NORTH Details of Locations with Land Line & Bandwidth - 256 Kbps Sl.No Division Sub-Division Name & Address of the office with Land Line No. of PCs Contact Number where VPNoBB Number connected with Existing Proposed Connectivity is available the VPNoBB Bandwidth Bandwidth connectivity 1 Ponneri AEE/O&M/ AE/O&M/ Medur, 33/11 KV SS, 044-27978902 3 256 256 Panjetty Medur, PonneriTaluk, Thiruvallur DT, Chennai- 601 204 2 Ponneri AEE/O&M/ AE/O&M/Irulipattu, 33/11 KV 044-27984204 3 256 256 Gummidipoon Irulipet SS campus, Irulipet, di Chennai – 600067 3 Ponneri AEE/O&M/ AE/O&M/ Pulicat, Pabanarishi 044-27976329 3 256 256 East Ponneri temple, Pulicat, Pin -601205 4 Ponneri AEE/West/ AE/W/Ponneri, Shankar Nagar, 044-27972368 2 256 256 Ponneri Ponneri 601204 5 Ponneri AEE/O&M/ AE/O&M/ Arani, 1, Thottakar Street, 044-27927265 3 256 256 Panjetty Arani, Chennai- 601 101 6 Ponneri AEE/O&M/ AE/O&M/ Kavarapettai, 465, 044-27925238 3 256 256 Kavarapettai GNT Road, Kavarapettai, GummidipoondiTaluk, Thiruvallur District, PIN 601206 7 Tondiarpet AEE/O&M/ AE/O&M/ Tiruvellavoyal, 33/11 044-27980675 2 256 256 Minjur Thiruvallavoil SS, Minjur - Kattur Road, Thiruvallavoil Village (P.O) , Ponneri Taluk, Chennai-601203 8 Ponneri AEE/O&M/ AE/O&M/ Panjetty, SF. No. 044-27975242 2 256 256 Panjetty 79/2, Thatchur-Ponneri Road, Panjetty, PIN- 601204 Details of Locations with Land Line & Bandwidth - 512 Kbps Sl.No Division Sub-Division Name & Address of the office with Land Line No. of PCs Contact Number where VPNoBB Number connected with Existing Proposed Connectivity is available the VPNoBB Bandwidth Bandwidth connectivity 1 T.Nagar Teynampet DMS SS, DMS Complex, Anna Salai, 044-24332950 3 512 512 Chennai – 6 2 T.Nagar Saidapet Thodunter Nagar SS, No.22, 044-24322211 3 512 512 Thodunter Nagar, Saidapet, CH- 15 3 T.Nagar Saidapet MHU SS, No.1 Link Road, MHU 044-24363191 1 512 512 Compound, CIT Nagar, Ch-35. -

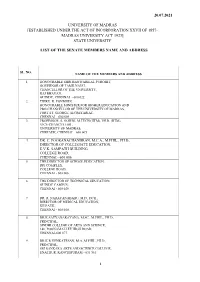

The Senate Members Name and Address

20.07.2021 UNIVERSITY OF MADRAS [ESTABLISHED UNDER THE ACT OF INCORPORATION XXVII OF 1857- MADRAS UNIVERSITY ACT 1923] STATE UNIVERSITY LIST OF THE SENATE MEMBERS NAME AND ADDRESS SL. NO. NAME OF THE MEMBERS AND ADDRESS 1. HONOURABLE SHRI BANWARILAL PUROHIT, GOVERNOR OF TAMILNADU, CHANCELLOR OF THE UNIVERSITY, RAJ BHAVAN, GUINDY, CHENNAI - 600 022 2. THIRU. K. PONMUDI, HONOURABLE MINISTER FOR HIGHER EDUCATION AND PRO-CHANCELLOR OF THE UNIVERSITY OF MADRAS, FORT ST. GEORGE, SECRETARIAT, CHENNAI – 600 009 3. PROFESSOR. S. GOWRI, M.TECH.(IITM), PH.D. (IITM), VICE-CHANCELLOR , UNIVERSITY OF MADRAS, CHEPAUK, CHENNAI – 600 005 4. DR. C. POORANACHANDRAN, M.C.A., M.PHIL., PH.D., DIRECTOR OF COLLEGIATE EDUCATION, E.V.K. SAMPATH BUILDING, COLLEGE ROAD, CHENNAI - 600 006 5. THE DIRECTOR OF SCHOOL EDUCATION, DPI COMPLEX, COLLEGE ROAD, CHENNAI - 600 006. 6. THE DIRECTOR OF TECHNICAL EDUCATION, GUINDY CAMPUS, CHENNAI - 600 025. 7. DR. R. NARAYANABABU, M.D., DCH., DIRECTOR OF MEDICAL EDUCATION, KILPAUK, CHENNAI - 600 010. 8. DR.K.SATYANARAYANA, M.SC., M.PHIL., PH.D., PRINCIPAL, SINDHI COLLEGE OF ARTS AND SCIENCE, 146, POONAMALLEE HIGH ROAD, CHENNAI-600 077. 9. DR.K.R.VENKATESAN, M.A.,M.PHIL.,PH.D., PRINCIPAL, SRI SANKARA ARTS AND SCIENCE COLLEGE, ENATHUR, KANCHIPURAM - 631 561. 1 10. DR. R. MEGANATHAN, M.COM.,M.PHIL.,M.B.A.,PH.D., PRINCIPAL, MOHAMED SATHAK COLLEGE OF ARTS AND SCIENCE, SHOLINGANALLUR, CHENNAI - 600 119. 11. DR. K. VENKATESAN, M.A., M.PHIL., PH.D., PRINCIPAL, KANCHI SHRI KRISHNA COLLEGE OF ARTS AND SCIENCE, KILAMBI, KRISHNAPURAM, KANCHIPURAM - 631 551. 12. DR.S.RAMANATHAN, M.COM.,M.PHIL., PH.D., PRINCIPAL, ASAN MEMORIAL COLLEGE OF ARTS AND SCIENCE, VELACHERRY-TAMBARAM ROAD, JALADAMPET, CHENNAI- 600 100. -

COMMISSIONERATE of LABOUR the Commissionerate of Labour Is

COMMISSIONERATE OF LABOUR The Commissionerate of Labour is effectively enforcing various Central and State Labour Legislations with a greater focus on protecting the interests of the workers engaged in both organized and unorganized sectors. The department is implementing various labour legislations to maintain good industrial relations, protecting the welfare of workers, promoting social security and redress the grievances of consumers. The Commissionerate of Labour is functioning in the Tamil Nadu Labour Welfare Board Building at D.M.S. Compound, Teynampet, and Chennai-6. The Commissioner of Labour is the Head of the Department with three Additional Commissioners of Labour working to discharge administration, conciliation and legal metrology functions and two Joint Commissioners of Labour at the Head quarters. There are four Zonal Additional Commissioners of Labour and ten Regional Joint Commissioners of Labour who are entrusted with the implementation of various welfare Schemes for unorganized workers and enforcement of various Labour laws for organized workers and Quasi judicial functions within their respective territorial jurisdiction. At the district level, Assistant Commissioners of Labour (Enforcement) are appointed to enforce the various Labour Legislations including the Legal Metrology Act. The Deputy Inspectors of Labour, Assistant Inspectors of Labour and Stamping Inspectors are enforcing the legislations at sub-district level. Conciliation Officers in the cadre of Deputy Commissioner of Labour / Assistant Commissioner of Labour are appointed in each district to settle industrial disputes. The Plantations Labour Act, 1951 and its rules have been framed to provide for the welfare of the plantation labour and to regulate the conditions of work in plantations. The Additional Commissioner of Labour (Administration) / Chief Inspector of Plantations is supervising and 2 monitoring the enforcement of Plantations Labour Act 1951. -

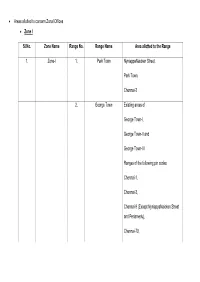

• Areas Allotted to Concern Zonal Offices • Zone I Sl.No. Zone Name Range No. Range Name Area Allotted to the Range 1. Zone

• Areas allotted to concern Zonal Offices • Zone I Sl.No. Zone Name Range No. Range Name Area allotted to the Range 1. Zone-I 1. Park Town NyniappaNaicken Street, Park Town, Chennai-3 2. George Town Existing areas of George Town-I, George Town-II and George Town-III Ranges of the following pin codes: Chennai-1, Chennai-3, Chennai-9 (Except NyniappaNaicken Street and Periamedu), Chennai-79, Chennai-108. 3. Tondiarpet-I Existing Tondiarpet-I areas of Chennai Corporation. 4. Tondiarpet-II Existing Tondiarpet-II areas of Chennai Corporation. 5. Egmore Chennai Corporation postal pin code: Chennai-8, Chennai-34 and Periamedu, Chennai-3. 6. Veppery Chennai Corporation postal pin code: Chennai-7, Chennai-112. 7. Perambur Chennai Corporation postal pin code: Chennai-11, Chennai-12. 8. Vysarpadi Chennai Corporation postal pin code: Chennai-118, Chennai-39 and Chennai-51. Zone-II Sl.No. Zone Name Range No. Range Name Area allotted to the Range 2. Zone-II 9. Arumbakkam Chennai Corporation postal pin code: Arumbakkam, Chennai-106, Ammjikarai, Chennai-29, Koyembedu, Chennai-107. 10. Anna Nagar Chennai Corporation postal pin code: Anna Nagar, Chennai-4, Shenoy Nagar, Chennai-30, Anna Nagar West Extn., Chennai-101. Of Pre-extended Chennai Corporation (of Chennai Revenue District). 11. Ayanavaram Chennai Corporation postal pin code: Ayanavaram, Chennai-23, Periyar Nagar, Chennai-82. 12. Villivakkam Chennai Corporation postal pin code: Villivakkam, Chennai-49, Kolathur, Chennai-99, Anna Nagar East, Chennai-102. 13. Kilpauk Chennai Corporation postal pin code: Kilpauk, Chennai-10, Flowers Road, Purasawakkam.. 14. Kodambakkam Chennai Corporation postal pin code: Kodambakkam, Chennai-24, Choolaimedu, Chennai-94. -

India COVID-19 Hospitals and Test Centres

1) NON NETWORK HOSPITALS Sr. Name of Hospital Address City PIN No. Plot No. 3&4, 1 Narayana Health Group Sadaramangala Bangalore 560066 Industrial Area 2 NH MMI Narayana Superspeciality Hospital - Raipur Dhamtari road, lalpur Raipur 492001 A Block, Near Kela 3 Fortis Hospital Shalimar Bagh Godown, NEW DELHI, New Delhi 110088 DELHI, Mulund Goregaon Link 4 Fortis Hospitals Ltd - Mulund Road, MUMBAI, Mumbai 400078 MAHARASHTRA, On Kalyan -Shill Road, 5 Fortis Hospitals Ltd - kalyan Thane 421301 Kalyan 5 th floor, mini seashore Navi 6 Hiranandani Hospital (Fortis) road, sector-10, Vashi, 400703 Mumbai Navi Mumbai CA#8, Ideal Homes 7 SSNMC Super Speciality Hospital Bangalore 560098 Township, 8 Apollo Hospitals Sarita Vihar, NEW DELHI New Delhi 110076 Block J, Mayfield 9 CK Birla Hospital For Women-Gurgaon Gurgaon 122018 Garden, Sector 51 Mulund Goregaon Link Fortis Hospital (Telegram Channel - Fortis Mental 10 Road, MUMBAI, Mumbai 400078 Health) MAHARASHTRA, 11 Manipal Hospital 98, HAL Airport Road, Bangalore 560017 Dr Baba Saheb Bharat Ratna Dr Babasaheb Ambedkar Memorial 12 Ambedkar Road, Byculla Mumbai 400012 Hospital - Byculla East, Mumbai, M M Marg, RBI Staff 13 Jagjivan Ram Hospital - Mumbai Colony, Mumbai Mumbai 400008 Central, L M Nadkarni Marg, 14 Mumbai Port Trust Hospital - Wadala Mumbai 400037 Wadala East, Veera Desai Road, 15 Andheri Sports Complex - Mumbai Mumbai 400053 Andheri West New Mhada Colony, Municipal Capacity Building and Research (MCMCR) in 16 Savarkar Nagar, Mumbai 400076 Powai Chandivali, Powai, Taharpur Rd, Taharpur, 17 Rajeev Gandhi Super Speciality Hospital Taharpur Village, New Delhi 110093 Dilshad Garden, Tahirpur Rd, GTB 18 GTBH (Guru Teg Bahadur Hospital) Enclave, Dilshad New Delhi 110095 Garden, Jawahar Lal Nehru 19 LNH (Lok Nayak Hospital) New Delhi 110002 Marg, Central, Maulana Azad Medical College Campus, 20 LNH (MAIDS) New Delhi 110002 Bahadur Shah Zafar Marg, Metro Station, Bhagawan Mahavir 21 Dr. -

Hospital Name Address

SLNO ZONE WARD HOSPITAL NAME ADDRESS 1 01-Thiruvottyur 001 SUMITHIRA CLINIC K.H. ROAD KATHIVAKKAM THALANKUPPAM 600057 2 01-Thiruvottyur 001 URBAN HEALTHPOST KAMARAJ NAGAR KATHIVAKKAM KAMARAJ NAGAR 600057 3 01-Thiruvottyur 001 SRI VEGNESH CLINIC C-15,THLANKUPPAM MAIN ROAD KATHIVAKKAM ULAGANATHAPURAM 600057 4 01-Thiruvottyur 001 S.S. CLINIC 6,6TH STREET KATHIVAKKAM ULAGANATHAPURAM 600057 5 01-Thiruvottyur 001 JAI CLINIC 3,7TH STREET ULAGANATHAPURAM THALANKUPPAM 600057 6 01-Thiruvottyur 001 JAI ASHWIN CLINIC 4, SATHYAVANI MUTHU NAGAR 7TH STREET, ENNORE, CHENNAI 600057 7 01-Thiruvottyur 001 SRI VEGNESH CLINIC C-15,THALANKUPPAM MAIN ROAD KATHIVAKKAM ULAGANATHAPURAM 600057 8 01-Thiruvottyur 002 RAJA CLINIC GIRIYAPPATHOTTAM KATHIVAKKAM SIVANPADAI VEEDHI 600057 9 01-Thiruvottyur 002 SRI VENUGOPAL CLINIC R.S. ROAD KATHIVAKKAM VALLUVAR NAGAR 600057 10 01-Thiruvottyur 002 SRI VENKATESWARA CLINIC K.H. ROAD KATHIVAKKAM SANJAIGANDHI NAGAR 600057 11 01-Thiruvottyur 002 THANGAMMAL CLINIC K.H. ROAD KATHIVAKKAM KATTUKUPPAM 600057 12 01-Thiruvottyur 002 MATERNITY CENTRE VILLAGE STREET KATHIVAKKAM SIVANPADAI VEEDHI 600057 13 01-Thiruvottyur 002 VIJAYA CLINIC THLANKUPPAM KATHIVAKKAM THALANKUPPAM 600057 14 01-Thiruvottyur 002 IPP-V HOSPITAL 03/592,K.H. ROAD KATHIVAKKAM K.H.ROAD 600057 15 01-Thiruvottyur 002 IPP-V HOSPITAL KAMARAJ NAGAR 5TH STREET KATHIVAKKAM KAMARAJ NAGAR 600057 16 01-Thiruvottyur 002 VIJAYA CLINIC GANDHI NAGAR KATHIVAKKAM GANDHI NAGAR 600057 17 01-Thiruvottyur 004 SELVA CLINIC & MATERNITY CENTR 72,KAMARAJ NAGAR THIRUVOTTIYUR ERNAVOOR 600019