INTRODUCTION 1. Although Jung Reportedly Stated, “Shakespeare

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Roots of Middle-Earth: William Morris's Influence Upon J. R. R. Tolkien

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 12-2007 The Roots of Middle-Earth: William Morris's Influence upon J. R. R. Tolkien Kelvin Lee Massey University of Tennessee - Knoxville Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_graddiss Part of the Literature in English, British Isles Commons Recommended Citation Massey, Kelvin Lee, "The Roots of Middle-Earth: William Morris's Influence upon J. R. R. olkien.T " PhD diss., University of Tennessee, 2007. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_graddiss/238 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a dissertation written by Kelvin Lee Massey entitled "The Roots of Middle-Earth: William Morris's Influence upon J. R. R. olkien.T " I have examined the final electronic copy of this dissertation for form and content and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, with a major in English. David F. Goslee, Major Professor We have read this dissertation and recommend its acceptance: Thomas Heffernan, Michael Lofaro, Robert Bast Accepted for the Council: Carolyn R. Hodges Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School (Original signatures are on file with official studentecor r ds.) To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a dissertation written by Kelvin Lee Massey entitled “The Roots of Middle-earth: William Morris’s Influence upon J. -

Nancy Wilson Ross

Nancy Wilson Ross: An Inventory of Her Papers at the Harry Ransom Center Descriptive Summary Creator: Ross, Nancy Wilson, 1901-1986 Title: Nancy Wilson Ross Papers Dates: 1913-1986 Extent: 261.5 document boxes, 12 flat boxes, 18 card boxes, 7 galley folders (138 linear feet) Abstract: The papers of this American writer encompass her entire literary career and include manuscript drafts, extensive correspondence, and subject files reflecting her interest in Eastern cultures. Call Number: Manuscript Collection MS-03616 Language: English Access Open for research Administrative Information Acquisition Purchase, 1972 (R5717) Provenance Ross's first shipment of materials to the Ransom Center accompanied her husband Stanley Young's papers, and consisted of Ross's literary output to 1975, including manuscripts, publications, and research materials. The second, posthumous shipment contained manuscripts created since 1974, and all her correspondence, personal, and financial files, as well as files concerning the estate of Stanley Young. Processed by Rufus Lund, 1992-93; completed by Joan Sibley, 1994 Processing note: Materials from the 1975 and 1986 shipments are grouped following Ross's original order, with the exception of pre-1970, special, and current correspondence which were interfiled during processing. An index of selected correspondents follows at the end of this inventory. Repository: Harry Ransom Center, The University of Texas at Austin Ross, Nancy Wilson, 1901-1986 Manuscript Collection MS-03616 2 Ross, Nancy Wilson, 1901-1986 Manuscript Collection MS-03616 Biographical Sketch Nancy Wilson was born in Olympia, Washington, on November 22, 1901. She graduated from the University of Oregon in 1924, and married Charles W. -

Zanesville & Western: a Creative Dissertation

ZANESVILLE & WESTERN: A CREATIVE DISSERTATION by Mark Allen Jenkins APPROVED BY SUPERVISORY COMMITTEE: _________________________________________ Dr. Frederick Turner, Co-Chair _________________________________________ Dr. Charles Hatfield, Co-Chair _________________________________________ Dr. Matt Bondurant _________________________________________ Dr. Nils Roemer Copyright 2017 Mark Allen Jenkins All Rights Reserved ZANESVILLE & WESTERN A CREATIVE DISSERTATION by MARK ALLEN JENKINS, BA, MFA DISSERTATION Presented to the Faculty of The University of Texas at Dallas in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN HUMANITIES – AESTHETIC STUDIES THE UNIVERSITY OF TEXAS AT DALLAS May 2017 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS There are several significant people to thank in the development, creation, and refining of this dissertation, Zanesville & Western: A Creative Dissertation. Dr. Charles Hatfield supported me throughout the dissertation. His expertise on theoretical framing helped me develop an approach to my topic through a range of texts and disciplines. Dr. Frederick Turner encouraged me to continue and develop narrative elements in my poetry and took a particular interest when I began writing poems about southeastern Ohio. He encouraged me to get to the essence of specific poems through multiple drafts. Dr. Rainer Schulte, Dr. Richard Brettell, and Dr. Nils Roemer were my introduction to The University of Texas at Dallas. Dr. Schulte’s “Interdisciplinary Approaches to the Arts and Humanities” highlighted many of the strengths of our program, and “Crafting Poetry” provided useful insight into my own poetry as well as a thorough introduction international poetry. Dr. Brettell’s “Art and Anarchy” course expounded the idea that poets could be political in their lives and work, both overtly and implicitly. -

A DANGEROUS METHOD a Sony Pictures Classics Presentation a Jeremy Thomas Production

MOVIE REVIEW Afr J Psychiatry 2012;15:363 A DANGEROUS METHOD A Sony Pictures Classics Presentation A Jeremy Thomas Production. Directed by David Cronenberg Film reviewed by Franco P. Visser As a clinician I always found psychoanalysis and considers the volumes of ethical rules and psychoanalytic theory to be boring, too intellectual regulations that govern our clinical practice. Jung and overly intense. Except for the occasional was a married man with children at the time. As if Freudian slip, transference encountered in therapy, this was not transgression enough, Jung also the odd dream analysis around the dinner table or became Spielrein’s advisor on her dissertation in discussing the taboos of adult sexuality I rarely her studies as a psychotherapist. After Jung’s venture out into the field of classic psychoanalysis. attempts to re-establish the boundaries of the I have come to realise that my stance towards doctor-patient relationship with Spielrein, she psychoanalysis mainly has to do with a lack of reacts negatively and contacts Freud, confessing knowledge and specialist training on my part in everything about her relationship with Jung to him. this area of psychology. I will also not deny that I Freud in turn uses the information that Spielrein find some of the aspects of Sigmund Freud’s provided in pressuring Jung into accepting his theory and methods highly intriguing and at times views and methods on the psychological a spark of curiosity makes me jump into the pool functioning of humans, and it is not long before the of psychoanalysis and psychoanalytic theory and two great minds part ways in addition to Spielrein ‘swim’ around a bit – mainly by means of reading or surfing the going her own way. -

Un Método Peligroso. La Transferencia Amorosa, Un Siglo Después Ética Y Cine Journal, Vol

Ética y Cine Journal ISSN: 2250-5415 [email protected] Universidad de Buenos Aires Argentina Michel Fariña, Juan Jorge; Laso, Eduardo; Cambra Badii, Irene; Tomas Maier, Alejandra; Benyakar, Moty Un método peligroso. La transferencia amorosa, un siglo después Ética y Cine Journal, vol. 2, núm. 1, marzo, 2012, pp. 9-12 Universidad de Buenos Aires Disponible en: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=564459990001 Cómo citar el artículo Número completo Sistema de Información Científica Más información del artículo Red de Revistas Científicas de América Latina, el Caribe, España y Portugal Página de la revista en redalyc.org Proyecto académico sin fines de lucro, desarrollado bajo la iniciativa de acceso abierto Michel Fariña, Laso, Cambra Badii, Tomas Maier y Benyakar Ética y Cine Journal | Vol. 2 | No. 1 | 2012 | pp. 9-12 EDITORIAL Un método peligroso. La transferencia amorosa, un siglo después 1 Juan Jorge Michel Fariña, Eduardo Laso, Irene Cambra Badii, Alejandra Tomas Maier y Moty Benyakar Universidad de Buenos Aires Universidad del Salvador “A dangerous method” (David Cronenberg, 2011), Para Freud, que como lo prueban las cartas halladas aborda la relación amorosa que mantuvo Carl Jung siguió con preocupación el asunto, la conducta de Jung (Michael Fassbender) con su paciente Sabina Spielrein resultaba inadmisible, pero reflejaba un problema que no (Keira Knightley), bajo la mirada preocupada de era nuevo. Ya en 1880 el análisis de otra joven de veintiún Sigmund Freud (Viggo Mortensen). El presente número años, Berta Pappenheim (Anna O.), erráticamente de Ética & Cine está dedicado a identificar y analizar conducido por Joseph Breuer, y luego en 1889 el de Fanny algunas de las ricas cuestiones teóricas que se desprenden Moser (Emmy von N.), lo habían puesto sobre la pista. -

Hero, Shadow and Trickster; Three Archetypes in the Kingkiller Chronicle

Hero, Shadow and Trickster; Three Archetypes in The Kingkiller Chronicle Tapio Tikkanen Master’s Thesis English Philology Faculty of Humanities University of Oulu Autumn 2018 Table of contents 1 Introduction.............................................................................................................................1 2 The History of Archetypes.........................................................................................................2 2.1 Carl Jung and the Collective Unconscious...........................................................................2 2.2 James Frazer’s Anthropological Examinations....................................................................4 2.3 Maud Bodkin’s Application of Jungian Archetypes to Poetry..............................................6 2.4 Northrop Frye and the Archetypes of Literature.................................................................9 3 Outlining the Archetypes........................................................................................................11 3.1 The Hero.........................................................................................................................11 3.2 The Shadow....................................................................................................................14 3.3 The Trickster...................................................................................................................15 4 Archetypes and Fantasy...…………….........................................................................................17 -

COSMOS + TAXIS | Volume 8 Issues 4 + 5 2020

ISSN 2291-5079 Vol 8 | Issue 4 + 5 2020 COSMOS + TAXIS Studies in Emergent Order and Organization Philosophy, the World, Life and the Law: In Honour of Susan Haack PART I INTRODUCTION PHILOSOPHY AND HOW WE GO ABOUT IT THE WORLD AND HOW WE UNDERSTAND IT COVER IMAGE Susan Haack on being awarded the COSMOS + TAXIS Ulysses Medal by University College Dublin Studies in Emergent Order and Organization Photo by Jason Clarke VOLUME 8 | ISSUE 4 + 5 2020 http: www.jasonclarkephotography.ie PHILOSOPHY, THE WORLD, LIFE AND EDITORIAL BOARDS THE LAW: IN HONOUR OF SUSAN HAACK HONORARY FOUNDING EDITORS EDITORS Joaquin Fuster David Emanuel Andersson* PART I University of California, Los Angeles (editor-in-chief) David F. Hardwick* National Sun Yat-sen University, The University of British Columbia Taiwan Lawrence Wai-Chung Lai William Butos University of Hong Kong (deputy editor) Foreword: “An Immense and Enduring Contribution” .............1 Trinity College Russell Brown Frederick Turner University of Texas at Dallas Laurent Dobuzinskis* Editor’s Preface ............................................2 (deputy editor) Simon Fraser University Mark Migotti Giovanni B. Grandi From There to Here: Fifty-Plus Years of Philosophy (deputy editor) with Susan Haack . 4 The University of British Columbia Mark Migotti Leslie Marsh* (managing editor) The University of British Columbia PHILOSOPHY AND HOW WE GO ABOUT IT Nathan Robert Cockram (assistant managing editor) Susan Haack’s Pragmatism as a The University of British Columbia Multi-faceted Philosophy ...................................38 Jaime Nubiola CONSULTING EDITORS Metaphysics, Religion, and Death Corey Abel Peter G. Klein or We’ll Always Have Paris ..................................48 Denver Baylor University Rosa Maria Mayorga Thierry Aimar Paul Lewis Naturalism, Innocent Realism and Haack’s Sciences Po Paris King’s College London subtle art of balancing Philosophy ...........................60 Nurit Alfasi Ted G. -

Margaret Dolinsky

University of Plymouth PEARL https://pearl.plymouth.ac.uk 04 University of Plymouth Research Theses 01 Research Theses Main Collection 2014 FACING EXPERIENCE: A PAINTER'S CANVAS IN VIRTUAL REALITY Dolinsky, Margaret http://hdl.handle.net/10026.1/3204 Plymouth University All content in PEARL is protected by copyright law. Author manuscripts are made available in accordance with publisher policies. Please cite only the published version using the details provided on the item record or document. In the absence of an open licence (e.g. Creative Commons), permissions for further reuse of content should be sought from the publisher or author. This copy of the thesis has been supplied on condition that anyone who consults it is understood to recognise that its copyright rests with its author and that no quotation from the thesis and no information derived from it may be published without the author's prior consent. FACING EXPERIENCE: A PAINTER’S CANVAS IN VIRTUAL REALITY by MARGARET DOLINSKY A thesis submitted to the University of Plymouth in partial fulfillment for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY School of Art & Media Faculty of Arts In collaboration with Indiana University, Bloomington USA September 2014 Facing Experience: a painter's canvas in virtual reality Margaret Dolinsky Question: How can drawings and paintings created through a stream of consciousness methodology become a VR experience? Abstract This research investigate how shifts in perception might be brought about through the development of visual imagery created by the use of virtual environment technology. Through a discussion of historical uses of immersion in art, this thesis will explore how immersion functions and why immersion has been a goal for artists throughout history. -

Dreams, a User's Guide

THE CENTRE FOR APPLIED JUNGIAN STUDIES Dreams, a User’s Guide Dreams are the royal road to the unconscious - Sigmund Freud He who looks outside dreams, he who looks inside awakes - C. G. Jung www.appliedjung.com THE CENTRE FOR APPLIED JUNGIAN STUDIES www.appliedjung.com Understanding your dreams TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction to dream interpretation 2 Illumination (the first step) 7 How to capture a dream 7 Amplification (associations) 8 Amplifying the dream 9 Education (understanding the dream message) 10 Understanding the dream 11 Some sample dreams 12 Transformation 14 The real work 14 An example of dream interpretation from Sigmund Freud 15 © The Centre for Applied Jungian Studies page 1 THE CENTRE FOR APPLIED JUNGIAN STUDIES www.appliedjung.com Throughout history and across cultures one point has dreams as the “royal road to the unconscious.” His always been agreed on by all mystical schools, all the ground breaking book The Interpretation of Dreams being legendary metaphysicians and by all religions that published in 1900, was what first brought him to Jung’s Introduction sought to bring the neophyte closer to his or her God, attention and led to their collaborative work together. that is simply: the way to truth lies inside and it is this journey that needs to be undertaken if you want to Ultimately Jung and Freud parted ways in that they know your truth. chose to interpret the contents of the unconscious differently. The nature of this difference is not something Trust me when I tell you that no one else other then I will enter into here, except to say that it can be you posses the truth. -

Exploring a Jungian-Oriented Approach to the Dream in Psychotherapy

Exploring a Jungian-oriented Approach to the Dream in Psychotherapy By Darina Shouldice Submitted to the Quality and Qualifications Ireland (QQI) for the degree MA in Psychotherapy from Dublin Business School, School of Arts Supervisor: Stephen McCoy June 2019 Department of Psychotherapy Dublin Business School Table of Contents Chapter 1 Introduction……………………………………………………………………. 1 1.1 Background and Rationale………………………………………………………………. 1 1.2 Aims and Objectives ……………………………………………………………………. 3 Chapter 2 Literature Review 2.1 Introduction……………………………………………………………………………... 4 2.2 Jung and the Dream……………………………………………………………….…….. 4 2.3 Resistance to Jung….…………………………………………………………………… 6 2.4 The Analytic Process..………………………………………………………………….. 8 2.5 The Matter of Interpretation……...……………………………………………………..10 2.6 Individuation………………………………………………………………………….. 12 2.7 Freud and Jung…………………………………….…………………………………... 13 2.8 Decline of the Dream………………………………………………………..………… 15 2.9 Changing Paradigms……………………………………………………………....….. 17 2.10 Science, Spirituality, and the Dream………………………………………….………. 19 Chapter 3 Methodology…….……………………………………...…………………….. 23 3.1 Introduction to Approach…..………………………………………………………..... 23 3.2 Rationale for a Qualitative Approach..…………………………………………..……..23 3.3 Thematic Analysis..………………………………………………………………..….. 24 3.4 Sample and Recruitment...…………………………………………………………….. 24 3.5 Data Collection..………………………………………………………………………. 25 3.6 Data Analysis..………………………………………………………………………... 26 3.7 Ethical Issues……..……………………………………………………………….…... 27 Chapter 4 Research Findings…………………………………………………………… -

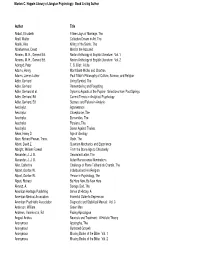

Alpha Author 0108

Marion C. Hoppin Library of Jungian Psychology: Book List by Author Author Title Abbott, Elisabeth Fifteen Joys of Marriage, The Abell, Walter Collective Dream in Art, The Abella, Alex Killing of the Saints, The Abrahamsen, David Mind of the Accused Abrams, M. H., General Ed. Norton Anthology of English Literature: Vol. 1 Abrams, M. H., General Ed. Norton Anthology of English Literature: Vol. 2 Ackroyd, Peter T. S. Eliot: A Life Adams, Henry Mont-Saint-Michel and Chartres Adams, James Luther Paul Tillich's Philosophy of Culture, Science, and Religion Adler, Gerhard Living Symbol, The Adler, Gerhard Remembering and Forgetting Adler, Gerhard et al. Dynamic Aspects of the Psyche: Selections from Past Springs Adler, Gerhard, Ed. Current Trends in Analytical Psychology Adler, Gerhard, Ed. Success and Failure in Analysis Aeschylus Agamemnon Aeschylus Choephoroe, The Aeschylus Eumenides, The Aeschylus Persians, The Aeschylus Seven Against Thebes Aiken, Henry D. Age of Ideology Alain; Richard Peaver, Trans. Gods, The Albert, David Z. Quantum Mechanics and Experience Albright, William Foxwell From the Stone Age to Christianity Alexander, J. J. G. Decorated Letter, The Alexander, J. J. G. Italian Renaissance Illuminations Aller, Catherine Challenge of Pierre Teilhard de Chardin, The Allport, Gordon W. Individual and His Religion Allport, Gordon W. Person in Psychology, The Alpert, Richard Be Here Now, Be Now Here Alvarez, A. Savage God, The American Heritage Publishing Sense of History, A American Medical Association Essential Guide to Depression American Psychiatric Association Diagnostic and Statistical Manual: Vol. 3 Anderson, William Green Man Andrews, Valerie et al, Ed. Facing Apocalypse Angyal, Andras Neurosis and Treatment: A Holistic Theory Anonymous Apocrypha, The Anonymous Illustrated Gospels Anonymous Missing Books of the Bible: Vol. -

Archetypal Approach to Eliot's “The Waste Land”

postscriptum: An Interdisciplinary Journal of Literary Studies, Vol: 1 (January 2016) Online; Peer-Reviewed; Open Access www.postscriptum.co.in Nandi, Rinku. “Archetypal Approach … ” pp. 57-66 Archetypal Approach to Eliot's “The Waste Land” Rinku Nandi Assistant Teacher (P.G.) of English, Baidyadanga Girls’ High School Abstract In literary criticism archetype denotes a primordial image. It is through primordial images that universal archetypes are experienced and the unconscious is revealed. In “The Waste Land” the central theme of sterility is expressed through the central myth of ‘death-rebirth archetype’ very minutely. Eliot uses the mythic mode with the archetypal approach in “The Waste Land”. This paper tries to capture this mythic sensibility, in its limited way, as expressed in “The Waste Land”. Keywords death, rebirth, sterility 58 Nandi Archetypal criticism is a branch of literary criticism which investigates and studies repetitive narrative structures, character types, themes, motifs and images that according to Carl Jung are universally shared by people of all cultures. These repetitive patterns are a result of universal forms on structures in the human psyche, which when presented well in literature immediately draw a strong response from the reader as he / she shares the archetypes expressed by the author. The anthropological origins of archetypal criticism can pre-date its psychoanalytic origins by over thirty years. The Scottish anthropologist, James G. Frazer, made significant contribution to this field when his work The Golden Bough (1890-1915) was published. He studied the elemental patterns of myth and ritual that recur in diverse cultures and religions. Frazer argues that the death-rebirth myth is present in almost all cultural mythologies and is acted out in terms of growing seasons and vegetation.