Trial by Machine

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Crime, Law Enforcement, and Punishment

Shirley Papers 48 Research Materials, Crime Series Inventory Box Folder Folder Title Research Materials Crime, Law Enforcement, and Punishment Capital Punishment 152 1 Newspaper clippings, 1951-1988 2 Newspaper clippings, 1891-1938 3 Newspaper clippings, 1990-1993 4 Newspaper clippings, 1994 5 Newspaper clippings, 1995 6 Newspaper clippings, 1996 7 Newspaper clippings, 1997 153 1 Newspaper clippings, 1998 2 Newspaper clippings, 1999 3 Newspaper clippings, 2000 4 Newspaper clippings, 2001-2002 Crime Cases Arizona 154 1 Cochise County 2 Coconino County 3 Gila County 4 Graham County 5-7 Maricopa County 8 Mohave County 9 Navajo County 10 Pima County 11 Pinal County 12 Santa Cruz County 13 Yavapai County 14 Yuma County Arkansas 155 1 Arkansas County 2 Ashley County 3 Baxter County 4 Benton County 5 Boone County 6 Calhoun County 7 Carroll County 8 Clark County 9 Clay County 10 Cleveland County 11 Columbia County 12 Conway County 13 Craighead County 14 Crawford County 15 Crittendon County 16 Cross County 17 Dallas County 18 Faulkner County 19 Franklin County Shirley Papers 49 Research Materials, Crime Series Inventory Box Folder Folder Title 20 Fulton County 21 Garland County 22 Grant County 23 Greene County 24 Hot Springs County 25 Howard County 26 Independence County 27 Izard County 28 Jackson County 29 Jefferson County 30 Johnson County 31 Lafayette County 32 Lincoln County 33 Little River County 34 Logan County 35 Lonoke County 36 Madison County 37 Marion County 156 1 Miller County 2 Mississippi County 3 Monroe County 4 Montgomery County -

Counter Information #42 March 1995

social struggles, such as claim- EVICTED - BUT ants’ resistance and opposi- tion to the M77. THE CENTRE We're still battling to re- open Broughton Street. 200 LIVES ON! demonstrated outside the A Centre activist reports: closed Centre on 10 Decem- 70 POLICE forcibly ended our ber. Ont Februarythe drum- tJ\\ 6 month occupation of ming at our demo drowned out Edinburgh’s Broughton St. the Council meeting! Both Centre on 1 December, demos were called without C‘ 1§\‘\tll\’ arresting 21 people. 80 people permission, in defiance of the l resisted the surprise eviction Criminal justice Act. Ni‘(mt for 8 hours. Labourcontrolled The struggle for self-man- Lothian Region were aged community spaces is an determined to shut a self- important part of the struggle managed community centre foraself-managedworldl Viva involved in direct action Ia Centre! struggles. The Centre is in the basement ofthe St Ten Yearsof Counter Information 1984 -94 But the Centre lives on! We Stephen Centre, St Stephen St (enter by lane at left of building). Open Mon March/April/May 1995 No.42 Free/Donation immediately found new tempo- - Friday 12 - 4 pm, meetings Tues rary premises, and continue to 6.30pm. tel 0131557 5846. Mail to give advice and solidarity on ben- The Centre, c/0 Peace & Justice, St Johns, Princes St, Edinburgh. Sup- efits and poll/council tax has- port eviction defendants -meet 9.30am sles, and to act as a base for Sheriff Court, Chambers St. 17 May. OVER the last 6 months, it site on Nov.7th. 400 Anti-CJA Centre supporters resist eviction in Edinburgh on 1 Dec. -

Durham E-Theses

Durham E-Theses Animal rights & human identity: a polemical quest for authenticity O'Neill, Pamela Susan How to cite: O'Neill, Pamela Susan (2000) Animal rights & human identity: a polemical quest for authenticity, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/4474/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk Pamela Susan O'Neill, University of Durham, Department of Anthropology. Thesis submitted for the degree of Master of Philosophy in Social Anthropology Thesis Title: Animal Rights & Human Identity: A Polemical Quest for Authenticity Abstract This thesis examines the hypothesis that 'The conflict between animal advocates and animal users is far more than a matter of contrasting tastes or interests. Opposing world views, concepts of identity, ideas of community, are all at stake' (Jasper & Nelkin 1992, 7). It is based on a year of anthropological fieldwork with a group of animal rights activists. -

Stalking Laws and Implementation Practices: a National Review for Policymakers and Practitioners

The author(s) shown below used Federal funds provided by the U.S. Department of Justice and prepared the following final report: Document Title: Stalking Laws and Implementation Practices: A National Review for Policymakers and Practitioners Author(s): Neal Miller Document No.: 197066 Date Received: October 24, 2002 Award Number: 97-WT-VX-0007 This report has not been published by the U.S. Department of Justice. To provide better customer service, NCJRS has made this Federally- funded grant final report available electronically in addition to traditional paper copies. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice. Institute for Law and Justice 1018 Duke Street Alexandria, Virginia 22314 Phone: 703-684-5300 Fax: 703-739-5533 i http://www. ilj .org -- PROPERTY OF National Criminal Justice Reference Service (NCJRS). t'Y- Box 6000 Rockville, MD 20849-6000 fl-- Stalking Laws and Implementation Practices: A 0 National Review for Policymakers and Practitioners Neal Miller October 2001 Prepared under a grant from the National Institute of Justice to the Institute for Law and Justice (ILJ), grant no. 97-WT-VX-0007 Any opinions expressed herein are solely those of the author and do not necessarily represent the views of the U.S. Department of Justice or ILJ. This document is a research report submitted to the U.S. Department of Justice. This report has not been published by the Department. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. -

Animal Rights in the British Broadsheet

Animal Rights in the British Broadsheet Andrew Owen Animal Rights in the British Broadsheet by Andrew Owen Published May 15, 1996 Copyright © 1996 Andrew Owen Abstract This dissertation charts the rise of animal rights as a movement in modern British politics and examines how broadsheet newspapers have reported this issue over the last three years. By discovering the relationship between successful organisations and those who have gained media attention we can see how a group can harness the media to improve its fortunes. The British animal rights movement, which began in the 1970s, is based on the belief that animals, like humans, have inalienable rights that must be protected. Over the last 25 years the movement has steadily gained acceptance and its membership has increased accordingly. The number of groups has mushroomed and the variety of causes has diversified to the extent that there are now hundreds of animal rights groups in Britain with very different aims. Methods have also changed over the years and there has been a steady move away from the violence of groups such as the Animal Liberation Front (ALF). New words such as ‘speciesism’ and ‘eco-terrorism’ have arisen out of the movement. I will begin by looking at the historical origins of the movement. From this it is possible to see how it has come to its current prominence over the last five years. Since 1994 hardly a day has gone by without at least one broadsheet newspaper in Britain printing a story about animal rights. Then I will move on to examine the framework of pressure group politics in which these organisations work, and to look closely at the methods they use to achieve their goals. -

Memory, Youth, Politica

____________________________________ ____________________________________ MYPLACE (Memory, Youth, Political Legacy and Civic Engagement) Grant agreement no: FP7-266831 WP5: Interpreting Participation (Interviews) Deliverable 5.3: Report on interview findings UNITED KINGDOM Editors Nickie Charles, Hilary Pilkington, Anton Popov, Khursheed Wadia Version 3 Date 30 November 2013 Work Package 5 Interpreting participation (Interviews) Deliverable 5.3 Country-based reports on interview findings Dissemination level PU WP Leaders Flórián Sipos Deliverable Date 30 November 2013 Document history Version Date Comments Modified by 1 01.11.13 First draft NC 2 21.11.13 Edited HP 3 30.11.13 Edited SF MYPLACE: FP7-266831 www.fp7-myplace.eu Deliverable 5.3: Country-based reports on interview findings–UK Page 1 of 67 Contents Introduction ................................................................................................................................ 3 1. Context ................................................................................................................................... 4 2. Methods.................................................................................................................................. 6 3. Demographic profile of respondents ...................................................................................... 8 4. Key findings ......................................................................................................................... 12 4.1 Living in Coventry and Nuneaton ................................................................................. -

List of the Harmed

List of the Harmed Online at http://pennsylvaniaallianceforcleanwaterandair.wordpress.com/the-list/ Compiled by Jenny Lisak -Updated as of June 11th, 2017- The following is an ever-growing list of the individuals and families that have been harmed by fracking (or shale gas production) in the US. Should you encounter any issues (misinformation, broken links, etc.) or if you are/know someone who should be added to this list, please contact us at [email protected] 1. Pam Judy and family Location: Carmichaels, PA Gas Facility: Compressor station 780 feet away Exposure: Air Symptoms: Headaches, fatigue, dizziness, nausea, nosebleeds, blood test show exposure to benzene and other chemicals http://www.marcellus-shale.us/Pam-Judy.htm 2. Darrell Smitsky Location: Hickory, PA Gas Facility: Range Resources Well, less than 1,000 ft Exposure: Water – toluene, acrylonitrile, strontium, barium, manganese Symptoms: Rashes on legs from showering. Symptoms (animal): Five healthy goats dead; fish in pond showing abnormal scales; another neighbor comments anonymously http://www.marcellus-shale.us/Darrell-Smitsky.htm 3. Jerry and Denise Gee and family Location: Tioga County, Charleston Township, PA Gas Facility: Shell Appalachia natural gas well Exposure: Water - methane Symptoms: Pond contaminated http://www.sungazettePond contaminated.com/page/content.detail/id/565860/Tioga-County- family-struggles-with-methane-in-its-well-water.html?nav=5011 4. Stacey Haney Location: Washington County, PA Gas Facility: Range Resources gas well and 7 acre waste impoundment Exposure: Water - glycol and arsenic Symptoms: Son - stomach, (liver and kidney) pain, nausea, fatigue and mouth ulcers; daughter - similar symptoms Symptoms (animal): Dogs – death; goat – death; horse - sick http://www.uppermon.org/Mon_Watershed_Group/minutes-23Mar11.html http://www.nytimes.com/2011/11/20/magazine/fracking-amwell-township.html?pagewanted=all 5. -

Social Work, Independent Realities & the Circle

Edith Cowan University Research Online Theses: Doctorates and Masters Theses 2006 Social work, independent realities & the circle of moral considerability: Respect for humans, animals & the natural world Thomas D. Ryan Edith Cowan University Follow this and additional works at: https://ro.ecu.edu.au/theses Part of the Social Work Commons Recommended Citation Ryan, T. D. (2006). Social work, independent realities & the circle of moral considerability: Respect for humans, animals & the natural world. https://ro.ecu.edu.au/theses/97 This Thesis is posted at Research Online. https://ro.ecu.edu.au/theses/97 Edith Cowan University Copyright Warning You may print or download ONE copy of this document for the purpose of your own research or study. The University does not authorize you to copy, communicate or otherwise make available electronically to any other person any copyright material contained on this site. You are reminded of the following: Copyright owners are entitled to take legal action against persons who infringe their copyright. A reproduction of material that is protected by copyright may be a copyright infringement. Where the reproduction of such material is done without attribution of authorship, with false attribution of authorship or the authorship is treated in a derogatory manner, this may be a breach of the author’s moral rights contained in Part IX of the Copyright Act 1968 (Cth). Courts have the power to impose a wide range of civil and criminal sanctions for infringement of copyright, infringement of moral rights and other offences under the Copyright Act 1968 (Cth). Higher penalties may apply, and higher damages may be awarded, for offences and infringements involving the conversion of material into digital or electronic form. -

How-To-Do-Animal-Rights-2015.Pdf

How to Do Animal Rights …legally, with confidence Second PDF edition Contents About This Guide 5 Author & Email 5 Animal Rights Motto 6 1 Introduction 1.1 The Broad Setting 7 - the big problem. 1.2 Mass Extinction 9 - we live in the Sixth Extinction. 1.3 Animal Holocaust 11 - we live in an enduring and worsening Animal Holocaust. 1.4 World Scientists' Warning to Humanity 12 - scientists attempt to alert the world to the impending catastrophe. 2 Philosophy: Key Topics 2.1 Animal Rights 16 - know what animal rights are. 2.2 Equal Consideration 21 - are animal and human moral interests equally important? 2.3 Animal Ethics 23 - defend your animal rights activism rationally. 2.4 Consequentialism 29 - the morality of your action depends only on its consequences. 2.5 Deontology 30 - the morality of your action depends only on doing your duty. 2.6 Virtue Ethics 31 - the morality of your action depends only on your character. 2.7 Comparing Philosophies 33 - comparing animal rights with ethics, welfare & conservation. 2.8 Deep Ecology 37 - contrasts with animal rights and gives it perspective. How to Do Animal Rights 3 Campaigning: Methods for Animal Rights 3.1 How to Start Being Active for Animal Rights 40 - change society for the better. 3.2 Civil Disobedience 46 - campaign to right injustice. 3.3 Direct Action 49 - a stronger form of civil disobedience. 3.4 Action Planning 55 - take care that your activities are successful. 3.5 Lobbying 60 - sway the prominent and influential. 3.6 Picketing 65 - protest your target visibly and publicly. -

SOC-Log Li S31IN

Niles SERVING NILES SINCE 1951 J.J. THURSDAY, MAY 17, A CIIICAO SUWTIMFSAtorpublication24/7 AT PION EERLOCAL.COM $2.00 I ra1d-Spec2012 INSIDE THE BEST IN ONE PLACE Book brings top chefs' recipes to your table PAGE 34 DIVERSIONS Artist advocates through work and in Life Carnations were passed out to shoppers at Golf Mili mall dunng a Mother's Day gift-ideas expo May 10. PAGE 5 FLOWER FOR THE LADY hOE CYGANOWSKIFOR SUN-TIMES MEDIA PAGE Bl Will They Find WhatYou T Have SOC-Log lIS31IN LS NO..L)lO(" To Offer? 8I1 DIlSfldS31IN .LSi 0959 $'SCooeod S31IN AèJtèIBIi id3cj j:j Advertising Pays... In Print and Online. OOOOoo 5T03 Bi'TgCg 6T0-3IQ1 Call: 847-486-9200 PIONEER PRESS u YOUR LOCAL SOURCE www.pioneerlocal.com 2 WWW.P10NEERL0CAL.COMI THURSDAY, MAY 17, 2012NIL MARINO REALTORS 5800 Dempster-Morton Grove Ontu! (847) 967-5500 LII (OUTSIDE ILLINOIS CALL i - 800 253 - 0021) MLS The Gold Standard www.ceritury2l marino.com i STONES ThROW TO AUSTIN PARKI JMMACULATE "GROVE MANOR" CONDO! STEPS FROM MANSFIELD PARK! flOUSE BEAUTIFULE Morton Grove.Just Listedl Well maintained 7 rm solid brickMorton Grove. .New Listing! Tastefully decorated largeMorton Grove. Immaculate & updated 7 rm brick Bi-!evel Des Plaines. Exquisite 5 bedroonV4 bath home with 3800 Ranch located in Park View School District 70! Hardwood 4 rm Condo located near shopping, transportation, forestwith open contemporary feel! Modern custom kitchen with sqft of unique elegance & comfort. Quality craftsmanship floors under carpet. Newer windows in spacious living rm, preserve & Prairie View Community Center/Health Club! 42" cabinets + eating area. -

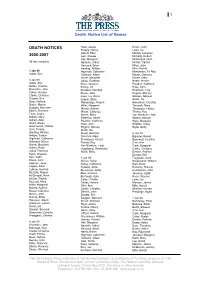

Death Notice List of Names

1 Death Notice List of Names DEATH NOTICES Fleet, Jessie Kroon, John Forbes, Nancy Laws, Ivy 2000-2007 Gilbert, Ellen Marfell, Leicester Gurr, Flossie McCully, Robert Hall, Margaret McDougall, Nora All lists complete Hamblin, Arthur McGirr, Patrick Hancock, Brian Miles, Joan Harding, William Mills, Harold 1 Jan 00 Highman, Catherine Mokomoko, Te Rau Adam, Eric Hubbard, Aileen Mooar, Clarence Hume, Margaret Moore, Mary 3 Jan 00 Julius, Florence Neale, Arnold Adam, Eric Keen, Graeme Paulden, Kathleen Belton, Charles Kenny, Jill Riley, John Brunsdon, Jack Knowles, Winifred Robinson, Lois Carter, Horace Kroon, John Rogers, Stanley Clarke, Christine Laws, Ivy Gloria Slooten, Adriaan Cooper, Eric Lepper, Elsie Smith, Iris Deer, Awhina Mansbridge, Robert Sweetman, Dorothy Drake, Marion Miller, Margaret Tannock, Mary Duggan, Maureen Monds, Aubrey Thompson, Hector Ellens, Florence Mooar, Clarence Timmo, Roy Fleet, Jessie Moore, Mary Van Workum, Liesji Gilbert, Mary Paterson, Albert Walker, Mervyn Gilbert, Alan Paulden, Kathleen West, Margaret Grant, Alison Riley, John Wratten, Craig Greenwood, William Rogers, Stanley Wylie, Betty Gurr, Flossie Smith, Iris Harding, William Stuart, Bernard 6 Jan 00 Hellyer, Evelyn Tannock, Mary Bigelow, Robert Highman, Catherine Thompson, Hector Bramwell, Youilline Hubbard, Aileen Timmo, Roy Chin, Kim Hume, Margaret Van Workum, Liesji Clark, Margaret Hutley, Rose Vogelzang, Geertruida Clarke, Christine Julius, Florence Wylie, Betty Denton, Patricia Keen, Graeme Donald, Eric Kerr, Keith 5 Jan 00 Ferguson, Cecil Kroon, -

Alleged Drunk Driver Is Held in Fatal Crash Son, Joey, Spent Long Hours Fiddling with After by LAURA QUINN School

Monday Ukrainian-Americans keep Watson finally wins Specials heritage alive: Family U.S. Open: Sports The Daily Register Monmouth County's Great Home Newspaper VOL.104 NO. 303 SHREWSBURY, N.J. MONDAY, JUNE 21, 1982 25 CENTS Princess Diana goes into labor LONDON (AP) — Princess Diana, pregnant When Princess Diana's trip to a shop to wife of Prince Charles, was admitted to Lon- satisfy a craving for fruit gum candies made the don's St. Mary's Hospital today "in the early front page of The Daily Mirror in December, stages of labor," Buckingham Palace an- Prince postpones polo match Queen Elizabeth II summoned British news- nounced. paper editors and heads of television and radio The brief announcement gave no other de- news to Buckingham Palace to request a halt. tails of her condition, but said she was admitted Press reports had said Diana wanted to have certain of being at his wife's bedside. The queen's press secretary told the news to the hospital between S a.m. and 6 a.m. — her baby in a hospital while Queen Elizabeth II It reportedly was the first time a helicopter chiefs that intrusive coverage of the private life midnight and 1 a.m. EDT. had preferred Buckingham Palace for the birth. had brought a member of the Royal Family of the 20-year-old princess, nicknamed by the Prince Charles, 33-year-old heir to the Brit- Charles returned to Kensington Palace, the home from abroad right to his own doorstep, on media "Shy Di," made her feel she "could not ish throne, accompanied his wife to the hospital, couple's London home, yesterday afternoon the lawns of Kensington Palace.