Michael Seman CIRP 6301

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

MSW Student Handbook

MSW Student Handbook College of Adult and Professional Studies School of Service and Leadership Department of Behavioral Sciences Master of Social Work Program 4201 S. Washington St. Marion, IN 46953 Phone 765.677.2363 Fax 765.677.1827 2021 Social Work Education Indiana Wesleyan University David King, DSW, MA, MSW, LMSW Program Director, Associate Professor, MSW Program [email protected] 734-657-8717 Cynthia Faulkner, Ph.D., MSW, LCSW Professor, MSW Program [email protected] (606) 356-7094 Brian Roland, Ph.D., MSW, LMSW Assistant Professor, MSW Program [email protected] 518-888-4121 Toby Buchanan, Ph.D., LMSW Professor, MSW Program [email protected] Marcie Cutsinger, Ed.D., MSW, LCSW Assistant Professor, MSW Program [email protected] 660.359.1856 James Long, Jr., Th.D., MSW, LCSW Associate Professor, Field Director, MSW Program [email protected] 201.341.5119 Katti Sneed Ph.D., MSW, LCSW Professor, Marion Hybrid Cohort, Director [email protected] 765-506-1391 Theresa Veach, Ph.D., HSPP Chair, Department of Behavioral Sciences School of Service and Leadership [email protected] 800.621.8667 / 756.677.2348 Kristy White Behavioral Sciences Administrative Assistant [email protected] 800.677.8667 / 765.677.2363 Social Work Advising MSW Program [email protected] 800-621-8667, ex 3323 / 765-677-332 2021 Table of Contents Message from the Director of the MSW Program .................................................................................................................. -

Razorcake Issue #82 As A

RIP THIS PAGE OUT WHO WE ARE... Razorcake exists because of you. Whether you contributed If you wish to donate through the mail, any content that was printed in this issue, placed an ad, or are a reader: without your involvement, this magazine would not exist. We are a please rip this page out and send it to: community that defi es geographical boundaries or easy answers. Much Razorcake/Gorsky Press, Inc. of what you will fi nd here is open to interpretation, and that’s how we PO Box 42129 like it. Los Angeles, CA 90042 In mainstream culture the bottom line is profi t. In DIY punk the NAME: bottom line is a personal decision. We operate in an economy of favors amongst ethical, life-long enthusiasts. And we’re fucking serious about it. Profi tless and proud. ADDRESS: Th ere’s nothing more laughable than the general public’s perception of punk. Endlessly misrepresented and misunderstood. Exploited and patronized. Let the squares worry about “fi tting in.” We know who we are. Within these pages you’ll fi nd unwavering beliefs rooted in a EMAIL: culture that values growth and exploration over tired predictability. Th ere is a rumbling dissonance reverberating within the inner DONATION walls of our collective skull. Th ank you for contributing to it. AMOUNT: Razorcake/Gorsky Press, Inc., a California not-for-profit corporation, is registered as a charitable organization with the State of California’s COMPUTER STUFF: Secretary of State, and has been granted official tax exempt status (section 501(c)(3) of the Internal Revenue Code) from the United razorcake.org/donate States IRS. -

Cocteau Twins, I Crepuscolari Del Pop Tornano Indipendenti

24VAR01A2410 ZALLCALL 12 20:54:37 10/23/97 LINEE eSUONI l’Unità2 9 Venerdì 24 ottobre 1997 Esce Star Rise, una raccolta di remix La band scozzese dopo il divorzio dalla Polygram ha creato l’etichetta Bella Union Time Zones La dance music & Bari, è partita Cocteau Twins, i crepuscolari la XII edizione la tradizione pakistana È cominciato ieri a Bari la XII edizione di Times Zones. E la manifestazione (nonostante Un album per capire del pop tornano indipendenti il disimpegno delle ammini- strazioni: il contributo alla Intervista con Simon Raymonde, uno dei tre membri del gruppo; il suo cd solista «Blame Some» è rassegna si riduce a 137 milio- la prima uscita dell’etichetta. «E in primavera i Cocteau tornano con un disco in due versioni». ni) continua a crescere. Sta- Nusrat Fateh Alì Khan volta la rassegna punta lo sguardo su discipline come la «Provo un grande senso di perdita, quantenario dell’indipendenza del L’uscita di Blame Some, esordio similitraloro». trovare nuovi spazi nei mezzi di co- danza, il teatro, la poesia. Ed la perdita di un artista straordinario e Pakistan. Star Rise è il tentativo di co- solista di uno dei tre Cocteau «Blame Some» ha qualcosa a municazione per far arrivare la sua ecco allora che ieri c’è stato lo la perdita di un amico... Non ho mai struire un’antologia che metta insie- Ticketmaster Twins, è anche il primo passo nel chefareconl’etichettadiscografi- musica a un pubblico nuovo, i loro spettacolo di danza «Sparta- sentitotale spirito in una voce».Que- me la dance music con echi e suoni mercato europeo di una nuova ca che hai fondato con i Cocteau sistemi non funzionano. -

Songs by Title Karaoke Night with the Patman

Songs By Title Karaoke Night with the Patman Title Versions Title Versions 10 Years 3 Libras Wasteland SC Perfect Circle SI 10,000 Maniacs 3 Of Hearts Because The Night SC Love Is Enough SC Candy Everybody Wants DK 30 Seconds To Mars More Than This SC Kill SC These Are The Days SC 311 Trouble Me SC All Mixed Up SC 100 Proof Aged In Soul Don't Tread On Me SC Somebody's Been Sleeping SC Down SC 10CC Love Song SC I'm Not In Love DK You Wouldn't Believe SC Things We Do For Love SC 38 Special 112 Back Where You Belong SI Come See Me SC Caught Up In You SC Dance With Me SC Hold On Loosely AH It's Over Now SC If I'd Been The One SC Only You SC Rockin' Onto The Night SC Peaches And Cream SC Second Chance SC U Already Know SC Teacher, Teacher SC 12 Gauge Wild Eyed Southern Boys SC Dunkie Butt SC 3LW 1910 Fruitgum Co. No More (Baby I'm A Do Right) SC 1, 2, 3 Redlight SC 3T Simon Says DK Anything SC 1975 Tease Me SC The Sound SI 4 Non Blondes 2 Live Crew What's Up DK Doo Wah Diddy SC 4 P.M. Me So Horny SC Lay Down Your Love SC We Want Some Pussy SC Sukiyaki DK 2 Pac 4 Runner California Love (Original Version) SC Ripples SC Changes SC That Was Him SC Thugz Mansion SC 42nd Street 20 Fingers 42nd Street Song SC Short Dick Man SC We're In The Money SC 3 Doors Down 5 Seconds Of Summer Away From The Sun SC Amnesia SI Be Like That SC She Looks So Perfect SI Behind Those Eyes SC 5 Stairsteps Duck & Run SC Ooh Child SC Here By Me CB 50 Cent Here Without You CB Disco Inferno SC Kryptonite SC If I Can't SC Let Me Go SC In Da Club HT Live For Today SC P.I.M.P. -

Dear Guest, We're Proud to Guide You Through Seward: When We Talk

Dear guest, We're proud to guide you through Seward: When we talk about up-and-coming bands that hold true promise for 2012, we talk about Seward. Atypical and spectacular, Seward is a visionary musical concept woven from traditional folk instruments; samples and effects; masterfully executed stop-start rhythms; driving, rage- ridden highs coupled with delicately-picked banjo melodies. Seward appear to ignore all modern rules about musical self-promotion, with no myspace or any other similar presence on the plethora of social networks available to musicians. In fact, currently the only way to experience Seward is by switching off the computer and actually going to a gig. Seward’s live spectacle is absorbing, intimate and bold. The togetherness of the band is evident, each of the quartet fully invested in this anonymous theatre, and lyrics are romantically solemn snapshots; nostalgic and moving. A band with a constructively critical eye on the surrounding musical terrain, and such boundless songwriting talent at this early stage in their life is not easy to come by. In Barcelona, they have not gone unnoticed, with notable appearances within the lineup of Primavera Sound 10′ & 11′ , BAM and Primavera Club 10′. With the release of Home in May 2011, the first installment in their suite of Eps, co-produced by Matt Pence (Centro-Matic, South San Gabriel, American Music Club, Micah P. Hinson…) in Denton, Texas, 2012 was set to be Seward’s year. This was confirmed by the amazing success gathered during their performances at SXSW, Canadian Music Week and The Great Escape. -

Toadies Bring Dia De Los Toadies Festival Home

TOADIES BRING DIA DE LOS TOADIES FESTIVAL HOME A DOZEN BANDS TO PLAY ACROSS TWO STAGES AT PANTHER ISLAND PAVILION IN SEPTEMBER AT SIXTH ANNUAL DIA DE LOS TOADIES FESTIVAL. FORT WORTH – After five years of hosting their annual end-of-summer throw down at various locations throughout the state, the Toadies are taking the sixth Dia De Los Toadies to their hometown of Fort Worth. This year’s festival, set to feature a dozen bands performing across two stages, will take place on Saturday, September 14, at Panther Island Pavilion, just minutes from downtown Fort Worth. Per tradition, the band will also host an intimate “fireside/almost acoustic” showcase on Friday, September 13, the evening before their day-long bash. Since Dia De Los Toadies 2008 debut, in conjunction with the band’s return-to-the-spotlight No Deliverance LP, the festival has evolved into one of the most hotly anticipated events on Texas’ yearly music calendar -- a carefully curated and reliably rocking affair that’s seen memorable performances from such celebrated acts as Ben Kweller, Black Angels, Black Joe Lewis and the Honeybears, Bowling for Soup, Centro-matic, Heartless Bastards, Helmet, Mariachi El Bronx, Riverboat Gamblers, The Secret Machines and The Sword, plus dozens of up-and-coming, underground acts from the Toadies home turf of Texas. “It's been great moving the Dia festival around Texas, but at a certain point, we realized that we need to share it with our hometown, Fort Worth, where the band is still based. We played Billy Bob's last year and it reminded us what a hometown crowd is like, so moving the festival made perfect sense,” says Toadies guitarist, Clark Vogeler. -

Soundgarden Badmotorfinger Mp3, Flac, Wma

Soundgarden Badmotorfinger mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Rock Album: Badmotorfinger Country: UK & Europe Released: 2016 Style: Alternative Rock, Hard Rock, Grunge MP3 version RAR size: 1567 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1577 mb WMA version RAR size: 1874 mb Rating: 4.5 Votes: 107 Other Formats: MMF DXD RA VOC WMA AU AAC Tracklist Hide Credits 1 Rusty Cage 4:26 2 Outshined 5:11 Slaves And Bulldozers 3 6:56 Music By – Shepherd*, Cornell* Jesus Christ Pose 4 6:51 Music By – Shepherd*, Cornell*, Thayil*, Cameron* Face Pollution 5 2:24 Music By – Shepherd* Somewhere 6 4:21 Music By, Lyrics By – Shepherd* 7 Searching With My Good Eye Closed 6:31 Room A Thousand Years Wide 8 4:06 Lyrics By – Thayil*Music By – Cameron* 9 Mind Riot 4:49 Drawing Flies 10 2:25 Music By – Cameron* 11 Holy Water 5:07 New Damage 12 5:40 Music By – Thayil*, Cameron* Companies, etc. Manufactured By – A&M Records Of Canada Limited Distributed By – PolyGram Distribution Inc. Phonographic Copyright (p) – A&M Records, Inc. Copyright (c) – A&M Records, Inc. Recorded At – Studio D Recorded At – Bear Creek Studios Recorded At – A&M Studios Mixed At – Can-Am Recorders Mastered At – Masterdisk Pressed By – Cinram Credits A&R – Bryan Huttenhower Art Direction – Len Peltier Bass – Ben Shepherd Design – Walberg Design Drums – Matt Cameron Engineer – Terry Date Engineer [Assisted By] – Efren Herrera Guitar – Kim Thayil Illustration [Front Cover] – Mark Dancey Lyrics By – Cornell* (tracks: 1 to 5, 7, 9 to 12) Management – Susan Silver Mastered By – Howie Weinberg Mixed By – Ron St. -

Toadies Vaden Todd Lewis - Vocals, Guitar Clark Vogeler - Guitar Mark Reznicek – Drums Doni Blair - Bass

Toadies Vaden Todd Lewis - vocals, guitar Clark Vogeler - guitar Mark Reznicek – drums Doni Blair - bass “There’s a certain uneasiness to the Toadies,” says Vaden Todd Lewis, succinctly and accurately describing his band—quite a trick. The Texas band is, at its core, just a raw, commanding rock band. Imagine an ebony sphere with a corona that radiates impossibly darker, and a brilliant circular sliver of light around that. It’s nebulous, but strangely distinct—and, shall we say incorrect. Or, as Lewis says, “wrong.” “Things are done a little askew [in the Toadies],” he says, searching for the right words. “There’s just something wrong with it that’s just really cool… and unique in a slightly uncomfortable way.” This sick, twisted essence was first exemplified on the band’s 1994 debut, Rubberneck (Interscope). An intense, swirling vortex of guitar rock built around Lewis’s “wrong” songs—like the smash single “Possum Kingdom,” subject to as much speculation as what’s in the Pulp Fiction briefcase, it rocketed to platinum status on the strength of that and two other singles, “Tyler” and “Away.” Its success was due to the Toadies’ organic sound and all-encompassing style, which they aimed to continue on their next album. Perhaps in keeping with the uneasy vibe, that success didn’t translate to label support when the Toadies submitted their second album, Feeler. Perhaps aptly, things in general just went wrong. It was the classic, cruel story: the label didn’t ‘get’ it. “These were the songs we played live,” says Rez. “It was pretty eclectic… different styles of heavy rock music—some fast, heavy punk rock songs and some slower, kinda mid-tempo stuff. -

March-30-2017-Weekend-Lineup.Pdf

Coming in April: AAYYEE! Cajun Rocks! Cover girl Elizabeth Kelley is first woman to win Texas Folklife's Big Squeeze Contest. She plays with her family in the Dallas Street Ramblers. She comes by it naturally, thanks to great-great-great Shop the Polka On! Store. grandma! Also, learn more about the Cajun CDs, DVDs, T-shirts, koozies, French Music Associations in Houston and San towels & more! Antonio, and dig the pics from Pe-Te's 35th Anniversary Party as DJ of Cajun Bandstand on Read the Polka On! blog. Houston's KPFT. Congrats Pe-Te! Editor Gary E. McKee delves into the music inspired by the Latest Posts road to Texas independence. (Yes, there is a Polka Man of the Hour - Danny Z photo of Fess Parker as Davy Crockett, er, David Crockett - turns out he didn't like being called Davy. Who knew?) We Dance Hall Art Contest Winners remember Helen Shimek Malick, great accordionist, Czech cook, and mom to 13! Announced We recognize some impressive milestones: Beethoven Maennerchor in San Antonio celebrated 150 years, New Baden Jamboree celebrated the 100th Polka Power Duo: Dujka birthday of its founder, and the Till twins - Alfred and Felix - celebrated their 90th Brothers Celebrate 30 Years birthday. Austin Accordion Association correspondent Marcus Baggio reports on the 30th National Accordion Convention recently held in Richardson; we reveal the It's Oktoberfest Man! high school winners of the Texas State German Contest; and of course we've got your calendar of events for April, including Janak's Church Picnics. Whew! It's a Accordion Cowboy Chris Rybak jam-packed issue! Says Na zdravi, Y'all! Have you subscribed yet? Come by the TPN table at the South Texas Polka & Texas Polka News Launches Sausage Festival this weekend and sign up! We'll have a special - $20, instead of Subscription Drive usual $25. -

Krist Novoselic, Dave Grohl, and Kurt Cobain

f Krist Novoselic, Dave Grohl, and Kurt Cobain (from top) N irvana By David Fricke The Seattle band led and defined the early-nineties alternative-rock uprising, unleashing a generation s pent-up energy and changing the sound and future of rock. THIS IS WHAT NIRVANA SINGER-GUITARIST KURT Cobain thought of institutional honors in rock & roll: When his band was photographed for the cover of Rolling Stone for the first time, in early 1992, he arrived wearing a white T-shirt on which he’d written, c o r p o r a t e m a g a z i n e s s t i l l s u c k in black marker. The slogan was his twist on one coined by the punk-rock label SST: “Corporate Rock Still Sucks.” The hastily arranged photo session, held by the side of a road during a manic tour of Australia, was later recalled by photogra pher Mark Seliger: “I said to Kurt, T think that’s a great shirt... but let’s shoot a couple with and without it.’ Kurt said, ‘No, I’m not going to take my shirt off.’” Rolling Stone ran his Fuck You un-retouched. ^ Cobain was also mocking his own success. At that moment, Nirvana - Cobain, bassist Krist Novoselic, and drummer Dave Grohl - was rock’s biggest new rock band, propelled out of a long-simmering postpunk scene in Seattle by its incendiary second album, N everm ind, and an improbable Top Ten single, “Smells Like Teen Spirit.” Right after New Year’s Day 1992, Nevermind - Nirvana’s first major-label release and a perfect monster of feral-punk challenge and classic-rock magne tism, issued to underground ecstacy just months before - had shoved Michael Jackson’s D angerous out of the Number One spot in B illboard. -

The 2007 Oxford Conference for the Book

Southern Register Winter 2k7 2/19/07 3:28 PM Page 1 the THE NEWSLETTER OF THE CENTER FOR THE STUDY OF SOUTHERN CULTURE •WINTER 2007 THE UNIVERSITY OF MISSISSIPPI 2007 Oxford Conference for the Book his year’s Oxford Conference for the Book will be a special one. The conference honors each year a Tprominent Southern writer, and Larry Brown will be the focus of attention when the 14th annual conference meets on March 22–24, 2007. Brown was one of the South’s, and nation’s, most acclaimed younger writers, when he died November 24, 2004. The conference will provide the first literary occasion to gather critics, scholars, musicians, teachers, friends, and family to consider and celebrate Brown’s achievements. Brown was an especially well known figure around Oxford. Having grown up in Lafayette County, he studied writing at the University of Mississippi, taught here briefly, and had been a frequent participant in Center work. Brown was a legendary figure—the Oxford firefighter who served the community from 1973 to 1990, when he retired to work full time on his writing. He studied with Mississippi writer Ellen Douglas, and his wide reading and relentless work on his writing contributed to his prolific success. He published his first book, Facing the Music: Short Stories, in 1988. He wrote five novels, a second short-story collection, and two books of nonfiction. His last novel, A Miracle of Catfish, will be published by Algonquin Books of Chapel Hill on March 20, just before the conference begins. Illustrating 2007 Oxford Conference for the Book materials is a Brown received the Mississippi Institute of Arts and Letters Larry Brown portrait made by Tom Rankin in 1996. -

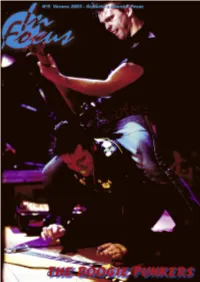

In Focus 5. Verano 2003. the Boogie Punkers. (PDF

Editorial Sumario LA CRÍTICA, EL CRÍTICO, EL CRITERIO REPORTAJES (004) Curiosos palabros estos tres. Al crítico no le (002) The Boogie Punkers gusta formar parte de la crítica pero se sabe (006) Los Del Tonos poseedor de criterio. El criticado cuando recibe (009) Doctor Deseo una buena crítica piensa que está hecha con cri- (015) Fito y Fitipaldis (016) Edu "Bighands" terio, así que si tiene ocasión se lo hace saber al (018) Gorka Gassman crítico, y el crítico, claro está, opina entonces que (020) Los Padrinos el criticado tiene criterio al criticar su crítica. (023) Sanchís y Jocano Suena críptico pero suele ser así. (027) Séan Keane (029) Tres Hombres Bien, ¿qué facultades debe tener un crítico? En (031) E- Bow el caso que nos ocupa, se supone que cultura (034) Bad- F Line musical. No problemo, si hay que escuchar dis- (036) The Cumshots cos, se escuchan, mola. Pero el problema está en (038) Dover las condiciones. Si eres de una discográfica y (040) El Drogas y el Kutxi quieres venderme a tu grupo, hazme el favor (043) Koniec (045) Mike Sobieski (ironía) de mandarme un disco, y no un Cd-R sin (046) Motorhead títulos, sin créditos, sin contactos y sin nada ("tie- (049) Obligaciones nes fotos en la güéf"). Si tu grupo está presen- (051) Los Reyes del KO tando su última grabación, no me entregues la (054) Peer Wyboris víspera de la rueda de prensa el disco ("por men- (058) Sharon Sahnnon (060) Shisha Pangma sajero, que corre prisa") y me sueltes encima la BREVES (062) puntilla: "les preguntas cuatro bobadas".