The Relationship Between Music Therapists'

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chapter 15: Resources This Is by No Means an Exhaustive List. It's Just

Chapter 15: Resources This is by no means an exhaustive list. It's just meant to get you started. ORGANIZATIONS African Americans for Humanism Supports skeptics, doubters, humanists, and atheists in the African American community, provides forums for communication and education, and facilitates coordinated action to achieve shared objectives. <a href="http://aahumanism.net">aahumanism.net</a> American Atheists The premier organization laboring for the civil liberties of atheists and the total, absolute separation of government and religion. <a href="http://atheists.org">atheists.org</a> American Humanist Association Advocating progressive values and equality for humanists, atheists, and freethinkers. <a href="http://americanhumanist.org">americanhumanist.org</a> Americans United for Separation of Church and State A nonpartisan organization dedicated to preserving church-state separation to ensure religious freedom for all Americans. <a href="http://au.org">au.org</a> Atheist Alliance International A global federation of atheist and freethought groups and individuals, committed to educating its members and the public about atheism, secularism and related issues. <a href="http://atheistalliance.org">atheistalliance.org</a> Atheist Alliance of America The umbrella organization of atheist groups and individuals around the world committed to promoting and defending reason and the atheist worldview. <a href="http://atheistallianceamerica.org">atheistallianceamerica.org< /a> Atheist Ireland Building a rational, ethical and secular society free from superstition and supernaturalism. <a href="http://atheist.ie">atheist.ie</a> Black Atheists of America Dedicated to bridging the gap between atheism and the black community. <a href="http://blackatheistsofamerica.org">blackatheistsofamerica.org </a> The Brights' Net A bright is a person who has a naturalistic worldview. -

The Princeton Seminary Bulletin

Catalogue of Princeton Theological Seminary 1923-1924 ONE HUNDRED AND TWELFTH YEAR The Princeton Seminary Bulletin Volume XVII, No. 4, January, 1924 Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2017 with funding from Princeton Theological Seminary Library https://archive.org/details/princetonsemina1741prin_0 4. President Stevenson, 86 Mercer St 15. Dr. Wilson, 73 Stockton St. 5. Dr. Loetscher, 98 Mercer St. 17. Dr. Dulles, 27 Boudinot St. 6. Dr. Hodge, 80 Mercer St 18. Dr. Machen, 39 Alexander Hall. 7. Dr. Armstrong, 74 Mercer St 19. Dr. Allis, 26 Alexander Hall. 8. Dr Davis, 58 Mercer St. 20. Missionary Apartment, 29 Alexander St. 9. Dr. Vos, 52 Mercer St. 21. Calvin Payne Hall. 10. Dr. J. R. Smith, 31 Alexander St. Mr. Jenkins, 309 Hodge Hall. 11. Mr. H. W. Smith, 16 Dickinson St. Mr. McCulloch, Calvin Payne Hall, Al. Catalogue of The Theological Seminary of The Presbyterian Church at Princeton, N. J. 1923-1924 One Hundred and Twelfth Year The Princeton Seminary Bulletin Vol. XVII, January, 1924, No. 4 Published quarterly by the Trustees of the Theological Seminary of the Presbyterian Church. Entered as second class matter. May. 1907, at the post^'office at Princeton, N. J. under the Act of Congress of July 16, 1894. 3 BOARD OF DIRECTORS MAITLAND ALEXANDER, D.D., LL.D., President Pittsburgh JOHN B. LAIRD, D.D., First Vice-President Philadelphia ELISHA H. PERKINS, Esq., Second Vice-President Baltimore SYLVESTER W. BEACH, D.D., Secretary Princeton J. ROSS STEVENSON, D.D., LL.D., ex-officio Princeton Term to Expire May, 1924 HOW.\RD DUFFIELD, D.D New York City WILLIAM L. -

April 2014 FFRF Complaints © a Better Life/Christopher Johnson Create Buzz

Complimentary Copy Join FFRF Now! Vo1. 31 No. 3 Published by the Freedom From Religion Foundation, Inc. April 2014 FFRF complaints Better Life/Christopher Johnson A © create buzz Rebecca Newberger Goldstein and Steven Pinker, photographed for Christopher Johnson’s A Better Life: 100 Atheists Speak Out on Joy & Meaning in a World Without God. March roared like a lion from begin- the board’s public censure. ning to end in winter-weary Wisconsin, Garnering at least of a week of me- and so did the Freedom From Religion dia attention in March was a letter from Pinker named FFRF’s Foundation, acting on many egregious Co-Presidents Dan Barker and Annie entanglements between religion and Laurie Gaylor to Green Bay Mayor Jim government. Schmitt, reprimanding him for invit- first honorary president FFRF’s complaints stirred up lots of ing the pope to visit the Wisconsin city regional and national news coverage, next year to make “a pilgrimage to the crank mail and crank callers, starting Shrine of Our Lady of Good Help.” with the March 3 announcement that Schmitt’s invitation on city let- religious incursions in science and gov- the Tennessee Board of Judicial Con- terhead was signed “Your servant in ernment, including testifying before duct agreed with FFRF that former Christ” and extolled in excited tones The Freedom From Religion Congress. He prevailed against a pro- magistrate Lu Ann Ballew violated “the events, apparitions and locutions” Foundation is delighted to announce posal at Harvard to require a course on codes of judicial conduct by ordering a in 1859 that “exhibit the substance that world-renowed scientist Steven “Reason and Faith,” saying, “[U]niver- boy’s named changed from Messiah to of supernatural character,” involving Pinker, already an honorary FFRF di- sities are about reason, pure and sim- Martin at an August hearing. -

Is Emerging Science Answering Philosopher: Greatest Questions?

free inquiry SPRING 2001 • VOL. 21 No. Is Emerging Science Answering Philosopher: Greatest Questions? ALSO: Paul Kurtz Peter Christina Hoff Sommers Tibor Machan Joan Kennedy Taylor Christopher Hitchens `Secular Humanism THE AFFIRMATIONS OF HUMANISM: LI I A STATEMENT OF PRINCIPLES free inquiry We are committed to the application of reason and science to the understanding of the universe and to the solving of human problems. We deplore efforts to denigrate human intelligence, to seek to explain the world in supernatural terms, and to look outside nature for salvation. We believe that scientific discovery and technology can contribute to the betterment of human life. We believe in an open and pluralistic society and that democracy is the best guarantee of protecting human rights from authoritarian elites and repressive majorities. We are committed to the principle of the separation of church and state. We cultivate the arts of negotiation and compromise as a means of resolving differences and achieving mutual under- standing. We are concerned with securing justice and fairness in society and with eliminating discrimination and intolerance. We believe in supporting the disadvantaged and the handicapped so that they will be able to help themselves. We attempt to transcend divisive parochial loyalties based on race, religion, gender, nationality, creed, class, sexual ori- entation, or ethnicity, and strive to work together for the common good of humanity. We want to protect and enhance the earth, to preserve it for future generations, and to avoid inflicting needless suf- fering on other species. We believe in enjoying life here and now and in developing our creative talents to their fullest. -

Ethics & Atheism

Ethics & Atheism © 2010 Photos.com, a division of Getty Images. All rights reserved. ANOTHER STUDY CONFIRMS: ATHEISTS “JUST AS ETHICAL AS CHURCHGOERS” he old canard that people who do not believe Both perceptions are incorrect. “At least a few TV in a “Supreme Being” are untrustworthy, with- preachers and other demagogues almost certainly and know- out morals, and unethical has received yet an- ingly encourage these misunderstandings, intentionally lying other rebuke. to shore up their own power and prestige. Atheists are al- According to a new study published in the ready serving in government, the armed forces, and the pro- journal Trends in Cognitive Sciences, Atheists are “just as fessions (even in the clergy); most just don't openly advertise Tethical as churchgoers,” and religion is only one way through the fact that they have no religious beliefs,” added Buckner. which people can manifest a moral code. Dr. Marc Hauser Dave Silverman, Vice President and Communications of Harvard University reported that his research team was Director for American Atheists added that the study dis- investigating the foundations of moral behavior and religion. cussed whether religion was an evolutionary adaptation “The research suggests that intuitive judgments of right which contributed to group solidarity and social cohesion. and wrong seem to operate independently of explicit reli- “It's a fascinating question that may never be resolved,” said gious commitments,” said Hauser. Silverman. “The point remains, though, that you can indeed, Dr. Ed Buckner, President of American Atheists, said be good without a god. In fact, you can be excellent! The that the study should help dispel one of the many great lies ethical actions of millions of Atheists, Freethinkers, Secular about non-religious Americans. -

The Wooster Voice

The College of Wooster Open Works The oV ice: 1951-1960 "The oV ice" Student Newspaper Collection 2-20-1959 The oW oster Voice (Wooster, OH), 1959-02-20 Wooster Voice Editors Follow this and additional works at: https://openworks.wooster.edu/voice1951-1960 Recommended Citation Editors, Wooster Voice, "The oosW ter Voice (Wooster, OH), 1959-02-20" (1959). The Voice: 1951-1960. 188. https://openworks.wooster.edu/voice1951-1960/188 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the "The oV ice" Student Newspaper Collection at Open Works, a service of The oC llege of Wooster Libraries. It has been accepted for inclusion in The oV ice: 1951-1960 by an authorized administrator of Open Works. For more information, please contact [email protected]. id miter 0 Published by the Students of the College of Wooster tt Volume LXXV Wooster, Ohio, Friday, February 20, 1959 Number 15 Trustees Increase Tuitition, Liberalize Loans Program Broadens Base CT1 Lowry Explains Reason For Financial Assistance For $100 Jump In Tuition A liberalized loan program and a new provision 4 v The Board of Trustees has voted to fix tuition and affecting some recipients of college and student aid ef- fees for the academic year 1959-196- 0 ot a total of fective with the Senior class of September 1960 f ft fs has been $900.00 for the year. The new rate thus represents an announced by the Board of Trustees. 1 If J increase of $100.00 over the present rate. The object of the first part of No the Board's action is to offer any event, repayment must be increases are scheduled in for greater opportunities for the use completed within 1 1 years of the the rates room and board. -

Lessons for Religious Liberty Litigation from Kentucky Jennifer Anglim Kreder

Washington and Lee Journal of Civil Rights and Social Justice Volume 19 | Issue 2 Article 5 3-1-2013 Lessons for Religious Liberty Litigation from Kentucky Jennifer Anglim Kreder Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.law.wlu.edu/crsj Part of the Civil Rights and Discrimination Commons, Human Rights Law Commons, and the Religion Law Commons Recommended Citation Jennifer Anglim Kreder, Lessons for Religious Liberty Litigation from Kentucky, 19 Wash. & Lee J. Civ. Rts. & Soc. Just. 275 (2013). Available at: https://scholarlycommons.law.wlu.edu/crsj/vol19/iss2/5 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Washington and Lee Journal of Civil Rights and Social Justice at Washington & Lee University School of Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Washington and Lee Journal of Civil Rights and Social Justice by an authorized editor of Washington & Lee University School of Law Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Lessons for Religious Liberty Litigation from Kentucky Jennifer Anglim Kreder* Table of Contents I. Introduction .................................................................................. 276 II. Establishment Clause Litigation Prospects for Nonbelievers ...... 279 A. School Litigation ................................................................... 283 B. Religious Displays Litigation ................................................ 287 1. Supreme Court Religious Displays Decisions ................ 288 2. Supreme Court “Ignored” -

2021 Commencement Program

Macalester College St. Paul, Minnesota The One Hundred and Thirty-Second COMMENCEMENT The Fifteenth of May Two Thousand and Twenty-One 1 MACALESTER COLLEGE In March 2021, Macalester College celebrated the 147th anniversary of its founding. The college received its charter from the State of Minnesota in 1874, and for the next several years its founders raised funds, hired faculty, planned courses, completed a classroom-office-residence building, and recruited students in preparation for Macalester’s opening in September 1885. The legacy of those founders—Presbyterian ministers and educators who strove for rigor and excellence—is a liberal arts college recognized for its academic excellence, its traditions of international and intercultural understanding, and its commitment to civic engagement. To carry out its educational mission, Macalester has assembled a distinguished faculty of 220 full-time and 70 part-time teachers and scholars who represent a broad array of disciplines in the natural sciences, social sciences, humanities, and fine arts. Macalester’s 2,009 full-time and 40 part-time students represent 50 states (and Washington, D.C.) in the United States and 95 other nations. Their academic achievements are numerous and impressive, as demonstrated by awards including 13 Rhodes Scholarships since 1904, and, in the last 10 years, 62 Fulbright Grants, 42 National Science Foundation Fellowships, 10 Thomas J. Watson Fellowships, four Truman Scholarships, four Goldwater Fellowships, one Beinecke Scholarship, and one Udall Scholarship. Macalester’s international emphasis is reflected in the fact that about 60 percent of its students study abroad for a semester or more during their college careers. -

FFRF, IRS Poised to Settle Church Politicking Suit

Vo1. 31 No. 6 Published by the Freedom From Religion Foundation, Inc. August 2014 FFRF, IRS poised to settle church politicking suit The Freedom From Religion Foun- dation and the Internal Revenue Service are poised to resolve FFRF’s closely watched federal lawsuit chal- lenging the IRS’s non-enforcement of anti-electioneering restrictions by tax- exempt churches. The expected settle- ment would be a major coup for FFRF, a state/church watchdog and the na- tion’s largest freethought association, now topping 21,000 members. FFRF and the IRS filed an agree- FFRF annual staff pic ment July 17 to dismiss the lawsuit vol- The federal courthouse in Madison, Wis., is two blocks from FFRF headquarters. Front, left are Sam Erickson, graphic untarily, after communications from design intern; Dayna Long, administrative assisant; Lisa Strand, director of operations; Lauryn Seering, publicist; Liz the IRS that it no longer has a policy Cavell, attorney; Katie Daniel, bookkeeper; Chelsea Culver, student staffer; Dan Barker, co-president; Jackie Douglas, of non-enforcement against churches. director of membership; and Annie Laurie Gaylor, co-president. However, the agreement is being dis- Back, left are Rebecca Markert, senior attorney; Aaron Loudenslager, legal intern; Bill Dunn, Freethought Today puted by an obscure Milwaukee-area editor; Scott Colson, IT manager; Todd Peissig, board member and volunteer; Neal Fitzgerald, legal intern; Sam Grover, church, Holy Cross Anglican Church, attorney; Noah Bunnell, editorial intern; Patrick Elliott, attorney; and Andrew Seidel, attorney. (Photo: Andrew Seidel) which is intervening in the case and is represented by the Becket Fund for Religious Liberty. -

The Advocate

* THE ADVOCATE PSYCHIATRIC DISORDERS CAN BE TREATED Volume 12, Number 3 April, 1990 THE ADVOCATE FEATURES Bourbon County Public Defender, Lee Greenup Lee Oreenup,our public defendercontract On its face, it is a difference of $109,621! administrator in Paris, his hometown, likes the quote of Oliver Wendell Holmes that"a man’s mind stretched by anew idea Leeplans to continue as a contract public can never go back to its original dimen defender for a yearor two and then focus sions." Lee has experienced that. Al on his general practice in Paris. He at though there are several lawyersin Lee’s tributes his many successes to his parents, who were "excellent role models." C.L. family,he didn’t getinterestedin law until Watts, Probation and Parole Officer of the his sophmore year at Transylvania when 14th Judicial Dist. of Ky. said, "I’ve hetook a pre-law course. Aftergraduating worked withLee fora long time and I’ve from theU.K. School ofLaw in 1983,Lee always found him honest, fair, above began practicing law in Paris. board and looking for the best results for all concerned. He is willing to do ajob that Lee never considered doing criminal requires a lot of timeand nevercomplains defense work, until the Bourbon Co. about low pay and long hours. I suppose public defender resigned in 1985. Lee he’s able to do that because he’s not a filled the breach and had some of his married man with a family. He’s a real "most satisfying moments as a lawyer." asset to your Department." We think so That led him to seek the contract for the too. -

May June 2010 FS Newsletter.Pub

The Freethought Society News Logo and website banner May/June 2010 Newsletter, Volume 1, Number 4 Editor: Margaret Downey and Various Volunteers contest details inside. Published by: The Freethought Society (a chapter of FFRF) Submissions sought. P.O. Box 242, Pocopson, PA 19366-0242 Phone: (610) 793-2737 * Fax: (610) 793-2569 See page 13. Email: [email protected] * Webpage: www.FtSociety.org Purchase Hepburn stamps and mail a letter to Carter! by Margaret Downey This is a Freethought Society (FS) action alert urging Many nontheist organizations around the country are nontheists around the country to visit local post offices to promoting the letter writing campaign. FS suggests that letters purchase Katharine Hepburn stamps. It was no coincidence to Mr. Carter be graced with the Hepburn stamp as a reminder that the Hepburn stamp was released to the public on May 12. that nontheists contribute to society in meaningful ways and Hepburn was born in Hartford, Connecticut on that day in should not be discriminated against. 1907. This “old-fashioned” letter-writing campaign is an effort to This call to purchase Hepburn stamps is not only to honor expose prejudices, negative stereotyping and blatant the memory of a great actress, but to also celebrate the fact disrespect of the nontheist community at the hands of BSA. that she was an atheist. In the October 1991 edition of the Ending discrimination against atheists would be a fitting Ladies Home Journal , Hepburn stated: tribute to Hepburn’s legacy. After six decades of involvement with the Southern Baptist I’m an atheist and that’s that. -

"Goodness Without Godness", with Professor Phil Zuckerman

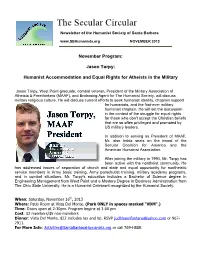

The Secular Circular Newsletter of the Humanist Society of Santa Barbara www.SBHumanists.org NOVEMBER 2013 November Program: Jason Torpy: Humanist Accommodation and Equal Rights for Atheists in the Military Jason Torpy, West Point graduate, combat veteran, President of the Military Association of Atheists & Freethinkers (MAAF), and Endorsing Agent for The Humanist Society, will discuss military religious culture. He will discuss current efforts to seek humanist identity, chaplain support for humanists, and the first-ever military humanist chaplain. He will set the discussion in the context of the struggle for equal rights for those who don't accept the Christian beliefs that are so often privileged and promoted by US military leaders. In addition to serving as President of MAAF, Mr. also holds seats on the board of the Secular Coalition for America and the American Humanist Association. After joining the military in 1994, Mr. Torpy has been active with the nontheist community. He has addressed issues of separation of church and state and equal opportunity for nontheistic service members in Army basic training, Army parachutist training, military academy programs, and in combat situations. Mr. Torpy's education includes a Bachelor of Science degree in Engineering Management from West Point and a Masters Degree in Business Administration from The Ohio State University. He is a Humanist Celebrant recognized by the Humanist Society. When: Saturday, November 16th, 2013 Where: Patio Room at Vista Del Monte. (Park ONLY in spaces marked "VDM".) Time: Doors open at 2:30pm. Program begins at 3:00 pm Cost: $2 members/$5 non-members Dinner: Vista Del Monte.