Billy Joel & the Law Conference

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Covering Joel with Perfect Pitch

Covering Joel with perfect pitch SUSAN DEEFHOLTS (Mar 23, 2007) One of the remarkable things about Billy Joel's music is that his writing has evolved with the times, while still retaining a sound that makes it distinctly his own. His work is uniquely contemporary, capturing a wide diversity of moods, from wry humour and sophisticated contemplation, through psychological angst and frenetic stress. An Innocent Man: The Music of Billy Joel marks the most recent in the Electric Thursdays series of concerts, a collaboration between the KWS and the Jeans 'n Classics band. Who better to lead us on this tribute to Joel's musical career than Jim Witter, himself an accomplished singer, pianist and songwriter? Witter is the creator of the hit show The Piano Men, a tribute to the 1970's hits of both Billy Joel and Elton John. His vibrant performance on Wednesday night potently demonstrated his strong affinity for Joel's work. At times, he sounded uncannily like the Piano Man himself, evoking both his timbre and enunciation. And yet, Witter also brought a presence that was uniquely his own to the performance. The evening began with such favourites as Only the Good Die Young and Uptown Girl --both songs about love between the kind of boy your mother warned you about and the girl who's got it all. The upbeat opening set the mood for a stellar performance of Joel classics. From the very first notes played, the audience sat up and took notice. Peter Brennan's orchestral arrangements, with Daniel Warren conducting, complemented the original songs, adding depth and resonance to the diverse range of songs covered throughout the evening. -

Billy Joel and the Practice of Law: Melodies to Which a Lawyer Might Work

Touro Law Review Volume 32 Number 1 Symposium: Billy Joel & the Law Article 10 April 2016 Billy Joel and the Practice of Law: Melodies to Which a Lawyer Might Work Randy Lee Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.tourolaw.edu/lawreview Part of the Legal Profession Commons Recommended Citation Lee, Randy (2016) "Billy Joel and the Practice of Law: Melodies to Which a Lawyer Might Work," Touro Law Review: Vol. 32 : No. 1 , Article 10. Available at: https://digitalcommons.tourolaw.edu/lawreview/vol32/iss1/10 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons @ Touro Law Center. It has been accepted for inclusion in Touro Law Review by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ Touro Law Center. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Lee: Billy Joel and the Practice of Law BILLY JOEL AND THE PRACTICE OF LAW: MELODIES TO WHICH A LAWYER MIGHT WORK Randy Lee* Piano Man has ten tracks.1 The Stranger has nine.2 This work has seven melodies to which a lawyer might work. I. TRACK 1: FROM PIANO BARS TO FIRES (WHY WE HAVE LAWYERS) Fulton Sheen once observed, “[t]he more you look at the clock, the less happy you are.”3 Piano Man4 begins by looking at the clock. “It’s nine o’clock on a Saturday.”5 As “[t]he regular crowd shuffles in,” there’s “an old man” chasing a memory, “sad” and “sweet” but elusive and misremembered.6 There are people who pre- fer “loneliness” to “being alone,” people in the wrong place, people out of time, no matter how much time they might have.7 They all show up at the Piano Man’s bar hoping “to forget about life for a while”8 because, as the song reminds us, sometimes people can find themselves in a place where their life is hard to live with. -

May – June 2014 Newsletter

MAY / JUNE 2014 Bring in Summer with the Gold Coast Public Library! Come One, Come All and Join us for our Second Annual Summer Kick - Off Weekend! Glenwood Landing American Legion Post 336, 190 Glen Head Road, Glen Head Start the Weekend Right with the Music of Billy Joel Friday, June 20th at 7:30PM Start the summer off right. Come on down to the American Legion with your neighbors for some great music! World famous, Pat Farrell and the Cold Spring Harbor Band will be performing Billy Joel's acclaimed repertoire, including such hits as Piano Man, New York State of Mind, Scenes from an Italian Restaurant and many more! And on Saturday, Enjoy A Day Full of Fun for the Kids and Teens Saturday, June 21st from 10:00AM - 2:00PM Bring your family and friends for a day fi lled with something for everyone! There will be craft tables, you can sign up for Summer Reading, and County Executive Mangano's Offi ce will be on hand to prepare Child Safety Kits. The Comedy Magic Circus Show (10:00AM) with Sammie & Tudie, “power couple of the clowning world,” is a thrill ride of fun perfect for all ages! Participate and laugh at this show full of slapstick comedy, playful magic and silly circus tricks. My Reptile Guys (11:30AM) ... a fi eld trip to the zoo-delivered to you! This interactive experience features twelve amazing reptiles, including a Burmese python, bearded dragon, and a baby alligator. There will also be a petting zoo! North Shore High School's own Mac, Dylan and Cody (1:00PM) will close out the day on a high note as they perform some of your favorite songs! Come Meet Best-Selling Author Ann Hood Wednesday, June 11th @ 7:00PM in the Library Annex The Gold Coast Public Library is thrilled to welcome novelist Ann Hood to discuss her novels, featuring women handling family issues, enjoying friendships, and dealing with tragedies large and small. -

The Ben Gray Lumpkin Collection of Colorado Folklore

Gene A. Culwell The Ben Gray Lumpkin Collection of Colorado Folklore Professor Ben Gray Lumpkin, who retired from the University of Colorado in June of 1969, spent more than twenty years of his academic career amassing a large collection of folksongs in the state of Colorado. At my request, Profes- sor Lumpkin provided the following information concerning his life and career: Son of John Moorman and Harriet Gray Lumpkin, I was born De- cember 25, 1901, in Marshall County, Mississippi, on a farm about seven miles north of Holly Springs. Grandpa was a Methodist cir- cuit rider, but had to farm to eke out a living because his hill-coun- try churches were too poor to support his family. Because we lived too far from the Hudsonville school for me to walk, I began schooling under my mother until I was old enough to ride a gentle mare and take care of her at school—at the age of 8. When my father bought a farm in Lowndes County, Mississippi, my brother Joe and sister Martha and I went to Penn Station and Crawford elementary schools. Having finished what was called the ninth grade, I went to live with my Aunt Olena Ford, and fin- ished Tupelo High School in 1921, then BA, University of Missis- sippi, 1925. I worked as the secretary and clerk in the Mississippi State Department of Archives and History (September 1925 to March 1929) and in the Mississippi Division office of Southern Bell Telephone Company (March 1929 to August 1930). I taught English and other subjects in Vina, Alabama, High School (August 1930 through January 1932). -

Billy Joel's Turn and Return to Classical Music Jie Fang Goh, MM

ABSTRACT Fantasies and Delusions: Billy Joel’s Turn and Return to Classical Music Jie Fang Goh, M.M. Mentor: Jean A. Boyd, Ph.D. In 2001, the release of Fantasies and Delusions officially announced Billy Joel’s remarkable career transition from popular songwriting to classical instrumental music composition. Representing Joel’s eclectic aesthetic that transcends genre, this album features a series of ten solo piano pieces that evoke a variety of musical styles, especially those coming from the Romantic tradition. A collaborative effort with classical pianist Hyung-ki Joo, Joel has mentioned that Fantasies and Delusions is the album closest to his heart and spirit. However, compared to Joel’s popular works, it has barely received any scholarly attention. Given this gap in musicological work on the album, this thesis focuses on the album’s content, creative process, and connection with Billy Joel’s life, career, and artistic identity. Through this thesis, I argue that Fantasies and Delusions is reflective of Joel’s artistic identity as an eclectic composer, a melodist, a Romantic, and a Piano Man. Fantasies and Delusions: Billy Joel's Turn and Return to Classical Music by Jie Fang Goh, B.M. A Thesis Approved by the School of Music Gary C. Mortenson, D.M.A., Dean Laurel E. Zeiss, Ph.D., Graduate Program Director Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of Baylor University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Music Approved by the Thesis Committee Jean A. Boyd, Ph.D., Chairperson Alfredo Colman, Ph.D. Horace J. Maxile, Jr., Ph.D. -

Press Kit Download

CELEBRATING THE MUSIC OF BILLY JOEL Starring: Anthony Mara More than just a Piano Man, Billy Joel is a living legend of the music industry with a catalogue of hit songs spanning more than 50 years. Anthony Mara and his world class band celebrate the musical journey of a remarkable career. The full live band consists of the finest musicians around, plus state of the art sound and lighting, in a powerful show that will mesmerise audiences with all the classic Billy Joel hits such as: “Piano Man”, “New York State Of Mind”, “Honesty”, “It’s Still Rock’n’roll To Me”, “Uptown Girl”, “We Didn’t Start The Fire”, “River Of Dreams” plus many more. Allow us to take you right into the world of Billy Joel in a 2 hour concert event not to be missed! [email protected] Ph: 1300 264 905 Available for Major Theatre Tours in both CBD and regional areas across Australia. Also available and can be tailored to suit Major Event and Corporate entertainment. www.BillyJoelTributeOz.com.au Sell-Out Shows in 2017 2018 PIANO MAN Tour The debut tour for the Billy Joel Tribute Concert Australia in 2017 In 2018, the bar was raised to a whole new level as the was titled NEW YORK STATE OF MIND and was a stunning Billy Joel Tribute Concert Australia set out on a 30 show full success with SELL-OUT shows across the country. scaled tour of the country, celebrating 45 Years since the It kicked off at the Palms Crown in Melbourne on May 19th, release of Billy’s signature song PIANO MAN.. -

Billy Joel Is World's First Bingelistening Artist of the Month! US

EDITION BingeListeningHuffPost #1: Billy Joel Is World's First BingeListening Artist Of The Month! US Michael Giltz, ContributorBookFilter creator BingeListening #1: Billy Joel Is World's First BingeListening Artist Of The Month! 09/15/2017 12:55 am ET Ok, what the heck is BingeListening? Well, you’ve heard of binge-watching, the ever-increasing trend of people consuming an entire season or even the entire run of a TV series in one fell swoop? It’s fun, it’s addictive and it reveals strengths and weaknesses of a show that you might miss when watching just one episode a week over a period of years. Binge-watch and you’ll love some TV shows more, you’ll like others less, you might discover a favorite you enjoyed as a kid doesn’t hold up and you’ll realize, “Yeah, Freaks & Geeks really is terrific.” So why should TV fans have all the fun? Let’s do the same with music — find an artist, listen to all their albums in order from start to finish and see what we think about them. Maybe it’s someone you never really listened to before. Maybe it’s a favorite you loved in high school or college but it’s been a while since you heard their newer stuff. Maybe it’s a legendary artist you know you really should give a listen to, just like you keep meaning to watch The Wire or Arrested Development or read War and Peace or Middlemarch...but you just haven’t made the time. One more reason to BingeListen to an artist’s body of work: the album. -

Song List 5/2016 1 | Page

Song List 5/2016 1 | Page Contemporary: Artist Rollin in the Deep Adele To Make You Feel My Love Adele I Found You Alabama Shakes Best Day of My Life American Authors Honey, I'm Good Andy Grammer Break Free Ariana Grande Wake Me Up Avicii Love On Top Beyoncé Crazy in Love Beyoncé Single Ladies (Put A Ring On It) Beyoncé I Gotta Feeling Black Eyed Peas Boom Boom Pow Black Eyed Peas Let’s Get it Started Black Eyed Peas Just the Way You Are Bruno Mars Locked Out of Heaven Bruno Mars Treasure Bruno Mars Uptown Funk Bruno Mars How Deep Is Your Love Calvin Harris Let's Go Calvin Harris Call Me Maybe Carly Rae Jepsen Forget You Cee Lo Green Yeah 3X Chris Brown Rather Be Clean Bandit Viva La Vida Cold Play Put Your Records On Corinne Bailey Rae Get Lucky Daft Punk Cake By The Ocean DNCE Thinking Out Loud Ed Sheeran Ex's And Oh's Elle King I Like It Enrique Iglesias Good Feelin’ Flo Rida Club Can't Handle Me Flo Rida I Don't Like It, I Love It Flo Rida Crazy Gnarles Barkley All Night Icona Pop I Love It Icona Pop Let It Go Idina Menzel Song List 5/2016 2 | Page Fancy Iggy Azalea Talk Dirty Jason Derulo On The Floor J Lo I Won't Give Up Jason Mraz Lucky Jason Mraz Empire State of Mind JayZ Domino Jesse J What Do You Mean Justin Bieber Can't Stop The Feeling Justin Timberlake Sexy Back Justin Timberlake The Good Life Kanye West Teenage Dream Katy Perry Firework Katy Perry Tic Tock Kesha Use Somebody Kings of Leon Applause Lady Gaga Born This Way Lady Gaga Bad Romance Lady Gaga Poker Face Lady Gaga Just Dance Lady Gaga Ho Hey Lumineers Rude MAGIC! -

Billy Joel: the Chronicler of the Suburbanization in New York

Touro Law Review Volume 32 Number 1 Symposium: Billy Joel & the Law Article 8 2015 Billy Joel: The Chronicler of the Suburbanization in New York Patricia E. Salkin [email protected] Irene Crisci Touro College Jacob D. Fuchsberg Law Center, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.tourolaw.edu/lawreview Part of the Environmental Law Commons, and the Land Use Law Commons Recommended Citation Salkin, Patricia E. and Crisci, Irene (2015) "Billy Joel: The Chronicler of the Suburbanization in New York," Touro Law Review: Vol. 32 : No. 1 , Article 8. Available at: https://digitalcommons.tourolaw.edu/lawreview/vol32/iss1/8 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons @ Touro Law Center. It has been accepted for inclusion in Touro Law Review by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ Touro Law Center. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Salkin and Crisci: Suburbanization in New York BILLY JOEL: THE CHRONICLER OF THE SUBURBANIZATION IN NEW YORK Patricia E. Salkin and Irene Crisci* I. INTRODUCTION Artists often chronicle historical developments through their chosen medium. In the case of Billy Joel, some of his lyrics can be traced to the early sustainability movements as he wrote about the migration of people from the cities and the attendant problems with rapid suburbanization. Described by Tony Bennett as “a poet, a per- former, a philosopher and today’s American songbook,”1 his lyrics address, among other topics, land use, community development, and environmental issues. Following World War II, there was a major shift in population settlement patterns in the United States. -

5F56f7cac79bc739603d20bb C

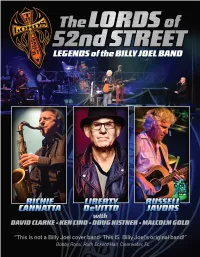

Before they were The Lords of 52nd Street, you could find them playing at local clubs in Long Island under the band name, “Topper.” Topper was a 1960s high school rock and roll band originally formed by, Russell Javors on guitar and vocals, Doug Stegmeyer on bass, and Liberty DeVitto on drums. The band was drawing a large audiences at the time, but bassist Doug Stegmeyer quickly flew out to California to audition for the “Piano Man,” Mr. Billy Joel. Joel was looking to form a new band that will record and tour with him regularly. Stegmeyer was immediately accepted into the Billy Joel Band, and Joel asked if Stegmeyer knew any other players, specifically a New York style drummer. Stegmeyer told Joel, “You know them,” and recommended his Topper bandmates, Russell Javors and Liberty DeVitto, for the part. Doug Stegmeyer, Liberty DeVitto and Russell Javors joined Billy Joel in studio to record his 1976 album “Turnstiles.” Billy Joel was also looking specifically for a saxophone player who can play keyboards. Al Stegmeyer, Doug Stegmeyer’s father, was a sound engineer on the album, and recommended Richie Cannata to play saxophone and keyboards on the album. Cannata walked into Ultrasonic Studios in Hempstead, New York, and heard for the first time the legendary hit, “Angry Young Man.” Joel, Stegmeyer, DeVitto and Javors recorded the tune a day earlier, and Cannata was blown away by their experienced playing and speed. Cannata went into the studio and immediately recorded the unforgettable Empire State love song, “New York State of Mind.” What made the music on this album so special, were the dedicated and loyal New York musicians behind its creation. -

JIM MECK's SONG LIST List Is Subject to Change at Any Time

JIM MECK'S SONG LIST List is subject to change at any time. ORIGINALS Words & Music by Jim Meck Along the Way; Asking for a Friend; Big Drops; Danger Zone; Days That End in Why; Designated Drinker; Flip Flops and Jello Shots; Follow the Music; Get Me Some; I Lose My Senses; Lackanookie Blues; Livin' in a Country Song; Lost in the Shuffle; More Than Ever; New Orleans; Noteworthy; One of These Days; The Only Time We Have Is Now; Organized Confusion; Reason to Live; Stay By My Side; Swingin' Doors Saloon; This Is My Katrina; This Is the Day; To Whom It May Concern; You Can Count on Me BILLY JOEL COLD SPRING HARBOR - She’s Got a Way; Everybody Loves You Now; Nocturne; Why, Judy Why PIANO MAN - Piano Man; Captain Jack; You’re My Home; The Ballad of Billy the Kid; Travelin' Prayer STREETLIFE SERENADE - The Entertainer; Souvenir; Root Beer Rag; The Mexican Connection TURNSTILES - New York State of Mind; Prelude/Angry Young Man; Summer, Highland Falls; James; I’ve Loved These Days; Miami 2017 (Seen the Lights Go Out on Broadway); Say Goodbye to Hollywood THE STRANGER - Movin' Out (Anthony's Song); Scenes from an Italian Restaurant; Only the Good Die Young; Just the Way You Are; Vienna; She’s Always a Woman 52nd STREET - Big Shot; Honesty; My Life; Rosalinda's Eyes; 52nd Street GLASS HOUSES - You May Be Right; It's Still Rock and Roll to Me; Don’t ask me Why THE NYLON CURTAIN - Allentown; Pressure; Goodnight Saigon THE BRIDGE - Baby Grand; Temptation STORMFRONT- I Go to Extremes; Shameless; And So It Goes; The Downeaster Alexa; Leningrad RIVER -

Scenes from the Copyright Office

Touro Law Review Volume 32 Number 1 Symposium: Billy Joel & the Law Article 7 April 2016 Scenes from the Copyright Office Brian L. Frye Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.tourolaw.edu/lawreview Part of the Intellectual Property Law Commons Recommended Citation Frye, Brian L. (2016) "Scenes from the Copyright Office," Touro Law Review: Vol. 32 : No. 1 , Article 7. Available at: https://digitalcommons.tourolaw.edu/lawreview/vol32/iss1/7 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons @ Touro Law Center. It has been accepted for inclusion in Touro Law Review by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ Touro Law Center. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Frye: Scenes from the Copyright Office SCENES FROM THE COPYRIGHT OFFICE Brian L. Frye* In his iconic song, “Scenes from an Italian Restaurant,” Billy Joel uses a series of vignettes to describe an encounter between two former classmates, meeting again after many years.1 The song begins as a ballad as they exchange pleasantries, segues into jazz as they reminisce about high school, shifts to rock as they gossip about the decline and fall of the former king and queen of the prom, then returns to a ballad as they part.2 The genius of the song is that the banality of the vignettes perfectly captures the subjective experience of its protagonists. This essay uses a series of vignettes drawn from Joel’s career to describe his encounters with copyright law. It begins by examining the ownership of the copyright in Joel’s songs.