The Phoenix Program: a Retrospective Assessment

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Air America in South Vietnam I – from the Days of CAT to 1969

Air America in South Vietnam I From the days of CAT to 1969 by Dr. Joe F. Leeker First published on 11 August 2008, last updated on 24 August 2015 I) At the times of CAT Since early 1951, a CAT C-47, mostly flown by James B. McGovern, was permanently based at Saigon1 to transport supplies within Vietnam for the US Special Technical and Economic Mission, and during the early fifties, American military and economic assistance to Indochina even increased. “In the fall of 1951, CAT did obtain a contract to fly in support of the Economic Aid Mission in FIC [= French Indochina]. McGovern was assigned to this duty from September 1951 to April 1953. He flew a C-47 (B-813 in the beginning) throughout FIC: Saigon, Hanoi, Phnom Penh, Vientiane, Nhatrang, Haiphong, etc., averaging about 75 hours a month. This was almost entirely overt flying.”2 CAT’s next operations in Vietnam were Squaw I and Squaw II, the missions flown out of Hanoi in support of the French garrison at Dien Bien Phu in 1953/4, using USAF C-119s painted in the colors of the French Air Force; but they are described in the file “Working in Remote Countries: CAT in New Zealand, Thailand-Burma, French Indochina, Guatemala, and Indonesia”. Between mid-May and mid-August 54, the CAT C-119s continued dropping supplies to isolated French outposts and landed loads throughout Vietnam. When the Communists incited riots throughout the country, CAT flew ammunition and other supplies from Hanoi to Saigon, and brought in tear gas from Okinawa in August.3 Between 12 and 14 June 54, CAT captain -

The Phoenix Program As a Case Study

Journal of Military and Strategic VOLUME 11, ISSUE 4, SPRING 2009 Studies The Theoretical Aspect of Targeted Killings: The Phoenix Program as a Case Study Dr. Tal Tovy One of the measures employed in the war against guerrilla warfare and terrorism is targeted killing, with the primary aim of directly attacking the higher-ranking activists, both military leaders and political cadres, of guerrilla or terror organizations and refraining, as far as possible, from injuring innocent citizens. This article has two purposes. First, it will examine the military theory that supports the mechanism for this kind of activity. Second, it will explain the essential nature of targeted killings as an operational tool, on the strategic and tactical levels, in the war against guerrilla warfare and terrorism. Therefore, we need to see the targeted killing as a warfare model of counterterrorism or counterinsurgency and not as a criminal action. The reason for combining these two concepts together is because no precise definition has yet been found acceptable to most researchers that distinguishes between a terror organization and a guerrilla organization.1 Eventually, the definition that will differentiate between the two concepts will be individually and subjectively linked with 1 Schmidt gives a long list of definitions he had collected from leading studies in the field of terror research. See: Alex P. Schmid, Political Terrorism: A Research Guide to Concepts, Theories, Data Bases and Literature, (New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction, 1987), pp. 5-152. Robert Kennedy, "Is One Person's Terrorist another's Freedom Fighters: Western and Islamic Approaches to ‘Just War’ Compared", in: Terrorism and Political Violence 11 (1: 1999): pp. -

The Tet Offensive 1968

The Tet Offensive 1968 Early in 1968 the Communists launched a major offensive to coincide with the traditional Vietnamese New Year celebrations (29 to 31 January). It was a time of an agreed cease-fire. NVA/VC suicide troops struck in Saigon, Hue was temporarily occupied, news media reported immense damage in the South, and 19 suicide sappers broke into the compound of the American Embassy. They were all killed. In all 80 different cities, towns or military bases were attacked, more or less simultaneously. The people of the South refused to rally to the cause as the NVA leaders had hoped and the whole thing was a military disaster. NVA General Giap was devastated. He felt that the gamble was a total waste. It was a resounding defeat for the NVA and VC. And then Walter Cronkite, America's most respected journalist at that time, suggested that America wasn't winning the war. It was inaccurate, based on a 30 second TV grab and was not much better than stupid as the figures will show. However it created the first significant crack in President Johnson's belief that he could win both the war and re-election. As it turned out he did neither. Growing reluctance in America to support a war it wasn't winning, combined with Johnson's new reticence and a NVA fresh surge of hope that these things bought, meant that the beginning of the end had been reached. Losses during Tet Offensive Country/Force Killed Wounded Missing US, Korea, Australia 1,536 7,764 11 South Viet Nam 2,788 8,299 587 North Viet Nam /Viet Cong 45,000 not known not known Civilian 14,000 24,000 Homeless 630,000 Hanoi was perfectly aware of the growing US peace movement and of the deep divisions the war was causing in American society. -

Operationchaos-CIA3.Pdf

C0009 6510· . ;:; .· .' (".~ - '·. e··.·.'":' · .~- ;,- ·• '· : ., . i . ~ ' . · .. ... .. ~ -- -~ - ~ .·.· . ·, . ' .. -··: .- . ~ •. ... SUBJECT: CIA Programs to Induce Desertions and . - ~: -:: . .. _, _ . , Defections in South Vietnam ..... ~ : 1. CIA conducts unilaterally or in coopera tion with other agencies in Vietnam a wide gamut of defector inducement programs which range from the.pin-pointed approach to high-level VC cadre to broad propaganda appeals to enemy troops of all categories. "' .. .. Inducement of Desertions ·. .- . 2. CIA and MACV jointly conduct a sizable program designed to induce desertion by VC and NVA soldiers. Through black radio and leaflets continuing . ". - ~ ~· ··.f:-: efforts are made to lower the morale of the individual enemy soldier to the point where he realizes the futility of his situation and begins to seek an alternative to .inevitable death. Radio and leaflet· out ·. ~ ,_, _:·. ·. : put emphasizes the endless sacrifice these soldiers are required to make, the awesome fire power they ·': .; : ·:: must face and the heavy· casualties their units endure. The privation caused by lack of sufficient food and ':_.•. medicine, the dissension between Northerner and . ··. :· Southerner·, the failure of the people of South Vietnam to support them except when forced to do so, and the failures and inadequacies of their own command and : .• ~ ... support structure are additional themes. Publicity is given to defections, particularly those involving high ranking officers and groups, and defectors are ... ~ ,. ·.. ·, .. · ... used in a variety of ways ·to attempt to induce the ,.:,.: r ~- · ';, -:· . ,. defection of their comrades. 1 Approved for Release Date 2 2 AUG .1996 ! C00096510 £;.... - ·.. ~·-; . , Rewards Program 3. The Station has also worked closely with MACV in the development of a program of awards utilized by both U.S. -

The United States and the Vietnam War: a Guide to Materials at the British Library

THE BRITISH LIBRARY THE UNITED STATES AND THE VIETNAM WAR: A GUIDE TO MATERIALS AT THE BRITISH LIBRARY by Jean Kemble THE ECCLES CENTRE FOR AMERICAN STUDIES THE UNITED STATES AND THE VIETNAM WAR Introduction Bibliographies, Indexes, and other Reference Aids Background and the Decision to Intervene The Congressional Role The Executive Role General Roosevelt Truman Eisenhower Kennedy Johnson Nixon Ford Carter Constitutional and International Law The Media Public Opinion Anti-war Protests/Peace Activists Contemporary Analysis Retrospective Analysis Legacy: Domestic Legacy: Foreign Policy Legacy: Cultural Art Film and Television Novels, Short Stories and Drama Poetry Literary Criticism Legacy: Human Vietnamese Refugees and Immigrants POW/MIAs Oral Histories, Memoirs, Diaries, Letters Veterans after the War Introduction It would be difficult to overstate the impact on the United States of the war in Vietnam. Not only did it expose the limits of U.S. military power and destroy the consensus over post-World War II foreign policy, but it acted as a catalyst for enormous social, cultural and political upheavals that still resonate in American society today. This guide is intended as a bibliograhical tool for all those seeking an introduction to the vast literature that has been written on this subject. It covers the reasons behind American intervention in Vietnam, the role of Congress, the Executive and the media, the response of the American public, particularly students, to the escalation of the war, and the war’s legacy upon American politics, culture and foreign policy. It also addresses the experiences of those individuals affected directly by the war: Vietnam veterans and the Indochinese refugees. -

I Will the CORDS Snap?

Will the CORDS Snap? Testing the Widely Accepted Assumption that Inter-Agency Single Management Improves Policy-Implementation by Patrick Vincent Howell Department of Political Science Duke University Date:_______________________ Approved: ___________________________ Peter Feaver, Chair ___________________________ David Rohde ___________________________ Kyle Beardsley, Supervisor ___________________________ Henry Brands Dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Political Science in the Graduate School of Duke University 2018 i v ABSTRACT Will the CORDS Snap? Testing the Widely Accepted Assumption that Inter-Agency Single Management Improves Policy-Implementation Title by Patrick Vincent Howell Department of Political Science Duke University Date:_______________________ Approved: ___________________________ Peter Feaver, Chair ___________________________ David Rohde ___________________________ Kyle Beardsley, Supervisor ___________________________ Henry Brands An abstract of a dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Political Science in the Graduate School of Duke University 2018 Copyright by Patrick Vincent Howell 2018 Abstract Since the end of the Cold War, the US Government’s difficulties in implementing policies requiring integrated responses from multiple agencies have led to a number of calls to reform USG inter-agency policy-implementation; similar to how the 1986 -

Phoenix Program - Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia 2/14/2014

Phoenix Program - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia 2/14/2014 Create account Log in Article Talk Read Edit View history Search Phoenix Program From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia For other uses of "Operation Phoenix", see Operation Phoenix (disambiguation). Main page The Phoenix Program (Vietnamese: Chiến dịch Phụng Hoàng, a word related to fenghuang, the Chinese phoenix) was a Contents program designed, coordinated, and executed by the United States Central Intelligence Agency (CIA), United States special Featured content operations forces, special forces operatives from the Australian Army Training Team Vietnam (AATTV),[1] and the Republic of Current events Vietnam's (South Vietnam) security apparatus during the Vietnam War. Random article Donate to Wikipedia The Program was designed to identify and "neutralize" (via infiltration, capture, Wikimedia Shop terrorism, torture, and assassination) the infrastructure of the National Liberation Front of South Vietnam (NLF or Viet Cong).[2][3][4][5] The CIA described it as "a set of Interaction programs that sought to attack and destroy the political infrastructure of the Viet Help Cong".[6] The major two components of the program were Provincial Reconnaissance About Wikipedia Units (PRUs) and regional interrogation centers. PRUs would kill or capture Community portal suspected NLF members, as well as civilians who were thought to have information Recent changes on NLF activities. Many of these people were then taken to interrogation centers Contact page where some were tortured in an attempt to gain intelligence on VC activities in the [7] Tools area. The information extracted at the centers was then given to military commanders, who would use it to task the PRU with further capture and Print/export assassination missions.[7] Languages The program was in operation between 1965 and 1972, and similar efforts existed Català both before and after that period. -

America and the Vietnam War Michael Hennessy

Document generated on 09/27/2021 3:23 a.m. Journal of Conflict Studies America and the Vietnam War Michael Hennessy Volume 16, Number 1, Spring 1996 URI: https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/jcs16_01re04 See table of contents Publisher(s) The University of New Brunswick ISSN 1198-8614 (print) 1715-5673 (digital) Explore this journal Cite this document Hennessy, M. (1996). America and the Vietnam War. Journal of Conflict Studies, 16(1), 160–162. All rights reserved © Centre for Conflict Studies, UNB, 1996 This document is protected by copyright law. Use of the services of Érudit (including reproduction) is subject to its terms and conditions, which can be viewed online. https://apropos.erudit.org/en/users/policy-on-use/ This article is disseminated and preserved by Érudit. Érudit is a non-profit inter-university consortium of the Université de Montréal, Université Laval, and the Université du Québec à Montréal. Its mission is to promote and disseminate research. https://www.erudit.org/en/ Vol. XVI No. 1, Fall 1997 Review Essay America and the Vietnam War Andradé, Dale. Trial By Fire. The 1972 Easter Offensive, America's Last Vietnam Battle. New York: Hippocrene Books, 1995. Hunt, Richard A. Pacification. The American Struggle for Vietnam's Hearts and Minds. Boulder, CO, San Francisco, CA and Oxford, UK: Westview, 1995. These two recent additions to Vietnam War history show both the continuing limitations and the maturation of the field. Andradé, the editor of the periodical, Vietnam, and the author of the well-received Ashes to Ashes: The Phoenix Program and the Vietnam War , (1990) provides a major contribution to the battle narratives of the latter half of the American phase of the war. -

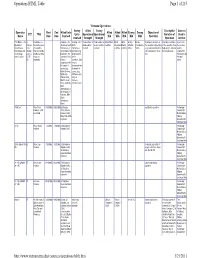

Page 1 of 215 Operations HTML Table 3/21/2011

Operations HTML Table Page 1 of 215 Vietnam Operations Enemy Allied Enemy Descriptive Sources Operation Start End Allied Units Allied Allied Allied Enemy Enemy Objective of CTZ TAO Units Operational Operational Narrative of Used in Name Date Date Involved KIA WIA MIA KIA WIA Operation Involved Strength Strength Operation Archive "The Name of the S. Description of A listing of the A listing of the Total number of Total number of Allied Killed- Allied Allied Enemy Enemy Descriptive narrative of Descriptive narrative A List of all Operation". Vietnam the tactical area American, South North allied soldiers enemy soldiers in-Action Wounded- Missing- Killed-in- Wounded-in- the operation's objectives of the operation from the sources Sometimes a Corps of operation. Vietnamese, or Vietnamese involved involved in-Action in-Action Action Action (e.g. search-and-destroy, beginning to end and used to Vietnamese and Tactical This can include other allied units and Viet Cong reconnaissance in force, its consequences. compile the an American Zone (I, provinces, cities, involved in the units involved etc.) information by name is given. II, III, towns, or operation. Each in the title and IV) landmarks. force is operation. Each author. designated with force is its branch of designated with service (e.g. its branch of USA=US Army, service (e.g. USMC=US PAVN=People's Marine Corps, Army of USAF= US Air Vietnam, Force, USN=US VC=Viet Cong) Navy, ARVN=Army of the Republic of Vietnam, VNN= South Vietnamese Navy) "Vinh Loc" I Thua Thien 9/10/1968 9/20/1968 2d -

The Vietnam War: a Blunder Or a Lesson? Is It Possible to Do Good by Doing History? an Interview with Mr, Fred Downey

The Vietnam War: A blunder or a lesson? Is it possible to do good by doing history? An interview with Mr, Fred Downey St. Andrew's Episcopal School Instructor Alex Haight Tenth of February 2003 By Abhi Naz OH NAZ 2003 Naz, Abhi Table of Contents Legal Restriction, signed release fonn Page 2 Statement of Puipose Page 3 Biography Page 4 Contextualization Paper on Vietnam: Page 5 The lives of millions of Americans were shattered; others lost respect for their own government; and governments and people throughout the world lost respect for America. - Joseph A. Aniter Interview Tianscription Page 23 Historical Analysis Page 45 Appendix A- US forces from 1959-1971 Page 52 Appendix B~ Comparative Strengths, 1975 Page 53 Appendix C - Demographics Page 54 Appendix D - One letter from Ho Chi Minli to Page 55 President Truman Appendix E - John Fitzgerald Kennedy - Page 56 Inaugural Address, Washington, D.C, 20 January, 1961 Appendix F - Map of Vietnam during War Page 59 Appendix G - Comparative size of Vietnam to Page 60 Eastern United States Appendix H-Map of Vietnam Page 61 Appendix I - Ho Chi Minh Trail Page 62 Appendix J - Ho Chi Minh Page 63 Bibliography Page 64 ST. ANDREW'S EPISCOPAL SCHOOL INTERVIEWEE RELEASE FORM: Tapes and Transcripts I, j\~t^€ V- ttu^fc: /A [)cnAi/\ey; do hereby give to the Saint Andrew's Episcopal name of interviewee ^ School all right, title or interest in the tape-recorded interviews conducted by I understand that these name of interviewer i^te(s) -^ inter\ lews will be protected by copyright and deposited in Saint Andrew's Library and Archives for the use of future students, educators and scholars. -

The Phoenix Program and Contemporary Counterinsurgency

THE ARTS This PDF document was made available from www.rand.org as a public CHILD POLICY service of the RAND Corporation. CIVIL JUSTICE EDUCATION ENERGY AND ENVIRONMENT Jump down to document6 HEALTH AND HEALTH CARE INTERNATIONAL AFFAIRS NATIONAL SECURITY The RAND Corporation is a nonprofit research POPULATION AND AGING organization providing objective analysis and effective PUBLIC SAFETY solutions that address the challenges facing the public SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY and private sectors around the world. SUBSTANCE ABUSE TERRORISM AND HOMELAND SECURITY TRANSPORTATION AND INFRASTRUCTURE WORKFORCE AND WORKPLACE Support RAND Purchase this document Browse Books & Publications Make a charitable contribution For More Information Visit RAND at www.rand.org Explore the RAND National Defense Research Institute View document details Limited Electronic Distribution Rights This document and trademark(s) contained herein are protected by law as indicated in a notice appearing later in this work. This electronic representation of RAND intellectual property is provided for non-commercial use only. Unauthorized posting of RAND PDFs to a non-RAND Web site is prohibited. RAND PDFs are protected under copyright law. Permission is required from RAND to reproduce, or reuse in another form, any of our research documents for commercial use. For information on reprint and linking permissions, please see RAND Permissions. This product is part of the RAND Corporation occasional paper series. RAND occasional papers may include an informed perspective on a timely policy issue, a discussion of new research methodologies, essays, a paper presented at a conference, a conference summary, or a summary of work in progress. All RAND occasional papers undergo rigorous peer review to ensure that they meet high standards for research quality and objectivity. -

Twin Threats: Main Forces and Guerrillas in Vietnam, the U.S

Dale Andrade and Lieutenant Colonel James H. Willbanks, U.S. Army, Retired, Ph.D. S THE UNITED STATES ends its third year forces were organized into regiments and divisions, Aof war in Iraq, the military continues to search and between 1965 and 1968 the enemy emphasized for ways to deal with an insurgency that shows no main-force war rather than insurgency.1 During the sign of waning. The specter of Vietnam looms large, war the Communists launched three conventional and the media has been filled with comparisons offensives: the 1968 Tet Offensive, the 1972 Easter between the current situation and the “quagmire” of Offensive, and the final offensive in 1975. All were the Vietnam War. The differences between the two major campaigns by any standard. Clearly, the insur- conflicts are legion, but observers can learn lessons gency and the enemy main forces had to be dealt from the Vietnam experience—if they are judicious with simultaneously. in their search. When faced with this sort of dual threat, what For better or worse, Vietnam is the most prominent is the correct response? Should military planners historical example of American counterinsurgency gear up for a counterinsurgency, or should they (COIN)—and the longest—so it would be a mistake fight a war aimed at destroying the enemy main to reject it because of its admittedly complex and forces? General William C. Westmoreland, the controversial nature. An examination of the paci- overall commander of U.S. troops under the Military fication effort in Vietnam and the evolution of the Assistance Command, Vietnam (MACV), faced just Civil Operations and Revolutionary Development such a question.