Angela's Ashes''

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

WILLIAM KENNEDY Conversations and Interpretations DONALD W

PRESS NEW BOOKS FOR 3 CONTENTS General Interest I 1–14 Asian Studies I 24–25 African American Studies I 23 Buddhist Studies I 15–17 Communication/Media Studies I 40 Cultural Studies I 20–21 Education I 50–57 Film Studies I 22 Gender Studies I 39 History I 41–42 Latin American Studies I 41 New in Paper I 58–64 Philosophy I 26–37 Political Science I 42–50 Psychology I 38 Religious Studies I 18–20 1100 Author Index I 72 Backlist Bestsellers I 65–66 Order Form I 68–70 Ordering Information I 67 Sales Representation I 71 Title Index I inside back cover State University of New York Press 194 Washington Avenue, Suite 305 Albany, NY 12210-2384 Phone: 518-472-5000 I Fax: 518-472-5038 www.sunypress.edu I email: [email protected] Cover art: Reproduction of a watercolor of the proposed design by Captain Williams Lansing of the Connecticut Street Armory, Buffalo, New York, by Hughson Hawley, 1896. Courtesy of New York State Division of Military and Naval Affairs. 1133 From Todd/ New York’s Historic Armories, p. 2. The Semitica fonts used to create this work are © 1986–2003 Payne Loving Trust. They are available from Linguist’s Software, Inc., www.linguistsoftware.com, P.O. Box 580, Edmonds, WA 98020-0580 USA, tel (425) 775-1130. GENERAL INTEREST WILLIAM KENNEDY Conversations and Interpretations DONALD W. FAULKNER, EDITOR Multiple perspectives on the author who has made Albany, New York an unavoidable stop on the route-map of the American literary landscape. -

Accelerated Reader List

Accelerated Reader Test List Report OHS encourages teachers to implement independent reading to suit their curriculum. Accelerated Reader quizzes/books include a wide range of reading levels and subject matter. Some books may contain mature subject matter and/or strong language. If a student finds a book objectionable/uncomfortable he or she should choose another book. Test Book Reading Point Number Title Author Level Value -------------------------------------------------------------------------- 68630EN 10th Grade Joseph Weisberg 5.7 11.0 101453EN 13 Little Blue Envelopes Maureen Johnson 5.0 9.0 136675EN 13 Treasures Michelle Harrison 5.3 11.0 39863EN 145th Street: Short Stories Walter Dean Myers 5.1 6.0 135667EN 16 1/2 On the Block Babygirl Daniels 5.3 4.0 135668EN 16 Going on 21 Darrien Lee 4.8 6.0 53617EN 1621: A New Look at Thanksgiving Catherine O'Neill 7.1 1.0 86429EN 1634: The Galileo Affair Eric Flint 6.5 31.0 11101EN A 16th Century Mosque Fiona MacDonald 7.7 1.0 104010EN 1776 David G. McCulloug 9.1 20.0 80002EN 19 Varieties of Gazelle: Poems o Naomi Shihab Nye 5.8 2.0 53175EN 1900-20: A Shrinking World Steve Parker 7.8 0.5 53176EN 1920-40: Atoms to Automation Steve Parker 7.9 1.0 53177EN 1940-60: The Nuclear Age Steve Parker 7.7 1.0 53178EN 1960s: Space and Time Steve Parker 7.8 0.5 130068EN 1968 Michael T. Kaufman 9.9 7.0 53179EN 1970-90: Computers and Chips Steve Parker 7.8 0.5 36099EN The 1970s from Watergate to Disc Stephen Feinstein 8.2 1.0 36098EN The 1980s from Ronald Reagan to Stephen Feinstein 7.8 1.0 5976EN 1984 George Orwell 8.9 17.0 53180EN 1990-2000: The Electronic Age Steve Parker 8.0 1.0 72374EN 1st to Die James Patterson 4.5 12.0 30561EN 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea (Ad Jules Verne 5.2 3.0 523EN 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea (Un Jules Verne 10.0 28.0 34791EN 2001: A Space Odyssey Arthur C. -

Seriality I Co Temporary America Memoir

SERIALITY I COTEMPORARY AMERICA MEMOIR: 1957-2007 A Dissertation by NICOLE EVE MCDANIEL-CARDER Submitted to the Office of Graduate Studies of Texas A&M University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY August 2009 Major Subject: English SERIALITY I COTEMPORARY AMERICA MEMOIR: 1957-2007 A Dissertation by NICOLE EVE MCDANIEL-CARDER Submitted to the Office of Graduate Studies of Texas A&M University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Approved by: Chair of Committee, Susan M. Stabile Committee Members, Pamela Matthews Linda Radzik Sally Robinson Head of Department, M. Jimmie Killingsworth August 2009 Major Subject: English iii ABSTRACT Seriality in Contemporary American Memoir: 1957-2007. (August 2009) Nicole Eve McDaniel-Carder, B.A., Sweet Briar College; M.A., Texas A&M University Chair of Advisory Committee: Dr. Susan M. Stabile In this dissertation, I examine the practice of what I term serial memoir in the second-half of the twentieth century in American literature, arguing that serial memoir represents an emerging and significant trend in life writing as it illustrates a transition in how a particular generation of writers understands lived experience and its textual representation. During the second-half of the twentieth century, and in tandem with the rapid technological advancements of postmodern and postindustrial culture, I look at the serial authorship and publication of multiple self-reflexive texts and propose that serial memoir presents a challenge to the historically privileged techniques of linear storytelling, narrative closure, and the possibility for autonomous subjectivity in American life writing. -

Directed by Maggie Mancinelli-Cahill Musical Direction by Josh D. Smith Choreography by Freddy Ramirez

Directed by Maggie Mancinelli-Cahill Musical Direction by Josh D. Smith Choreography by Freddy Ramirez FOR MORE INFORMATION, PLEASE CONTACT: MARGARET E. HALL AARON MARQUISE Associate Artistic Director Arts Education Manager [email protected] [email protected] 518.462.4531 x410 518.382.3884 x128 1 Table of Contents Capital Repertory Theatre’s 39th Season - 2019-2020 LOBBY HERO by Kenneth Lonergan 3 A Letter from our Education Department SEPT 29 – OCT 20, 2019 4 About Us 5 Attending a Performance IT’S A WONDERFUL LIFE 6 Literary Context: Synopsis of the Play Live from the WVL Radio Theatre Frank McCourt Bio Adapted by WVR Repoley from the motion From the Original Production picture by Frank Capra Vocabulary Words NOV 22 – DEC 22, 2019 10 Historical Context: Counties of Ireland Events Mentioned in the Script YOUR BEST ONE by Meridith Friedman Irish Potato Famine East Coast Premiere Immigration JAN 17 – FEB 09, 2020 Figures Mentioned in the Script 15 Scientific Context: Potato Blight THE IRISH AND HOW THEY GOT THAT WAY Famine and other Illnesses By Frank McCourt, featuring the music of 17 Musical Context: Songs … Ireland Instruments in the Show MAR 06 – APRIL 05, 2020 Song Sheet for 15 Miles on the Erie Canal 20 Who’s Who in the Production SISTER ACT 21 Ideas for Curriculum Integration Music by Alan Menken, Lyrics by Glenn Slater, 24 Resources Consulted Book by Cheri and Bill Steinkellner 25 Teacher Evaluation Based on the Touchstone Pictures Motion 26 theREP’s Mission In Action Picture, SISTER ACT, written by Joseph Howard *Parts of this guide were researched and written by Dramaturgy Intern Eliza Kuperschmid. -

A History and Narrative of Wynn Handman, The

THE LIFE BEHIND LITERATURE TO LIFE: A HISTORY AND NARRATIVE OF WYNN HANDMAN, THE AMERICAN PLACE THEATRE, AND LITERATURE TO LIFE A THESIS IN Theatre Presented to the Faculty of the University of Missouri-Kansas City in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree MASTER OF ARTS by TRACY TERSTRIEP-HERBER B.A., University of California, 1992 Kansas City, Missouri 2013 ©2013 TRACY TERSTRIEP-HERBER ALL RIGHTS RESERVED THE LIFE BEHIND LITERATURE TO LIFE: A HISTORY AND NARRATIVE OF WYNN HANDMAN, THE AMERICAN PLACE THEATRE, AND LITERATURE TO LIFE Tracy Terstriep-Herber, Candidate for the Master of Arts Degree University of Missouri-Kansas City, 2012 ABSTRACT Literature to Life is a performance-based literacy program developed under the auspices of The American Place Theatre in New York City (1994). The American Place Theatre was founded in 1964 and stewarded by the artistic mission of Wynn Handman. It has earned its own place in American theatrical history. Prior dissertations have chronicled specific elements of the American Place Theatre (APT), but no account has bridged the history of APT and Wynn Handman’s privately-run acting studio to the significant history of Literature to Life. The once New York City-based program that promoted English, cultural and theatrical literacy to students within the city’s public iii school system, now has a strong national following and continues to inspire students and adults across the country. This thesis will chart an historical and narrative account of Literature to Life as it emerged from the embers of the American Place Theatre and rekindled the original mission of Wynn Handman, in a different setting and for new audiences. -

Students in the Upper School Are Required to Read the Curious Incident of the Dog in the Night-Time by Mark Haddon

William Penn Charter School English Department Upper School Summer Reading List 2009 All students in the upper school are required to read The Curious Incident of the Dog in the Night-Time by Mark Haddon. In addition, students entering grades 9 through 12 will need to select two books from the list below to read over the summer. One of the choices must be from the FICTION section. STUDENTS MUST PICK THE REMAINING TWO BOOKS FROM THIS LIST UNLESS ALTERNATIVE SELECTIONS HAVE BEEN APPROVED BY THE ENGLISH DEPARTMENT CHAIR BY THE LAST DAY OF CLASSES. STUDENTS SHOULD ALSO BE AWARE THAT THEIR TEACHERS WILL EXPECT THEM TO BRING THEIR SUMMER READING BOOKS TO CLASS IN SEPTEMBER AND WILL BE HOLDING STUDENTS ACCOUNTABLE FOR THE READING. [Fiction] Agee, James. A Death in the Family 1957. The enchanted childhood summer of 1915 suddenly becomes a baffling experience for Rufus Follet when his father dies. Alcott, Louisa May. Little Women 1868. The story concerns the lives and loves of four sisters growing up during the American Civil War. It is based on Alcott’s own experiences as a child in Boston and Concord, Massachusetts. *Alexie, Sherman. The Absolutely True Diary of a Part-Time Indian. 2009. Budding cartoonist Junior leaves his troubled school on the Spokane Indian Reservation to attend an all-white farm town school where the only other Indian is the school mascot. Allen, Irene. Quaker Indictment 1998. Elizabeth Elliot, mild-mannered Quaker confronts murder, sexual harassment and plagiarism at Harvard. Also recommended: Wuaker Witness and Quaker Testimony. Anderson, Laurie Halse. -

Pulitzer Prize Winners and Finalists

WINNERS AND FINALISTS 1917 TO PRESENT TABLE OF CONTENTS Excerpts from the Plan of Award ..............................................................2 PULITZER PRIZES IN JOURNALISM Public Service ...........................................................................................6 Reporting ...............................................................................................24 Local Reporting .....................................................................................27 Local Reporting, Edition Time ..............................................................32 Local General or Spot News Reporting ..................................................33 General News Reporting ........................................................................36 Spot News Reporting ............................................................................38 Breaking News Reporting .....................................................................39 Local Reporting, No Edition Time .......................................................45 Local Investigative or Specialized Reporting .........................................47 Investigative Reporting ..........................................................................50 Explanatory Journalism .........................................................................61 Explanatory Reporting ...........................................................................64 Specialized Reporting .............................................................................70 -

Fiske Wordpower

New_Fiske Final 5/10/06 9:14 AM Page 1 Raise A POWERFUL VOCABULARY WILL OPEN UP Your THE MOST EFFECTIVE SYSTEM FOR BUILDING A WORLD OF OPPORTUNITY Word IQ A VOCABULARY THAT GETS RESULTS FAST With Fiske WordPower you will quickly learn to write FISKE more effectively, communicate clearly, score higher Raise Your W Learn on standardized tests like the SAT, ACT or GRE Word IQ 1,000 Words and be more confident and persuasive in everything in Weeks you do. OR FISKE Using the exclusive Fiske system, you will no longer need to memorize words.You will learn their meanings and how to use them correctly. The Fiske system will enhance and expand your permanent vocabulary. This knowledge will stay with you longer and be easier to recall—and it doesn’t take any longer than less-effective memorization. D Fiske WordPower uses a simple three-part system: WORD 1. Patterns: Words aren’t arranged randomly or alphabetically, but in P similar groups that make words easier to remember over time. 2. Deeper Meanings, More Examples: Full explanations—not just brief definitions—of what the words mean, plus multiple examples of OW the words in sentences. POWER 3. Quick Quizzes: Frequent short quizzes help you test how much you’ve learned, while helping you retain word meanings. words you need to know (and can 1,0001,000 learn quickly) to: ✔ Build a powerful and persuasive vocabulary Fiske WordPower— E ✔ The MOST EFFECTIVE vocabulary-building Raise your word IQ ✔ Communicate clearly and effectively system that GETS RESULTS FAST. R ✔ Improve your writing skills ✔ Dramatically increase your reading comprehension Study Aids $11.95 U.S. -

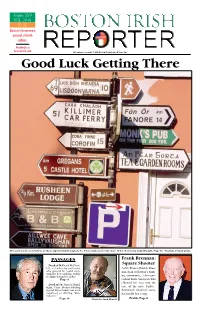

Good Luck Getting There

August 2009 VOL. 20 #8 $1.50 Boston’s hometown journal of Irish culture. Worldwide at bostonirish.com All contents copyright © 2009 Boston Neighborhood News, Inc. Good Luck Getting There All roads lead to somewhere as these signs in Ballyvaughan, Co. Clare, make perfectly clear. Related story by Judy Enright, Page 18. Tourism Ireland photo. PASSAGES Frank Brennan: Square Shooter Dead at 78: Frank McCourt, left, a teacher by profession At 92, Francis Patrick Bren- who proved he could write nan, dean of Boston’s bank- with the best with his widely acclaimed Angela’s Ashes. ing community, a first-gen- Page 4 eration Irish American who Dead at 54: Jerry Holland, elbowed his way into the right, Cape Breton fiddling core of the once Yankee- legend whose music has been dominated financial arena, described as offering “pure has hardly lost a step. radiance.” Page 14 Photo by Jack Rowell Profile, Page 6 Page August 009 BOSTON IRISH REPORTER Worldwide at www.bostonirish.com is pleased to sponsor the 6th Annual 8h_Wd>edWd+aRun/Walk IkdZWo"I[fj[cX[h(&"(&&/WjDeed >eij_d]hWY[#ZWoh[]_ijhWj_ed0 161 Brighton Ave., Allston, MA For more information, or to register, visit: www.BrianHonan.org The Brian J. Honan Charitable Fund was established to carry Brian J. Honan 5K the Charitable Fund has been able to support on Brian’s commitment to the causes that he championed and foster local and national programs that support education, throughout the course of his life. With funds raised from the recreation, housing and healthcare. FH;I;DJ;:8O0 IFEDIEH;:8O0 Worldwide at www.bostonirish.com August 009 BOSTON IRISH REPORTER Page Around Town: The Irish Beat / Carol Beggy Actor and standup comic Kevin Flynn was work- ing in New York during the winter months a couple of years ago, when he read about a spike in suicides among young residents of Nantucket. -

Class of 2019 High School Placements

MANHATTAN SCHOOL FOR CHILDREN Class of 2019 High School Placements The majority of MSC’s Class of 2019 received one of their top choices and many students received more than one high school acceptance (Academic plus Specialized High School or Performing Arts School). Last year’s High School placements were: Academic High Schools Specialized High Schools Beacon High School (5) American Studies High School/Lehman College (NEST) New Explorations into Science & Math Brooklyn Latin (2) Manhattan Center for Science & Mathematics Bronx Science High School NYC iSchool (2) Brooklyn Technical High School The Clinton School High School for Mathematics, Science and Xavier High School Engineering at City College Loyola High School West End Secondary School Frank McCourt High School (14) Pace (3) Performing Arts High Schools Environmental Studies High School (3) LaGuardia High School (5) [Program: Drama] Global Learning Collaborative (2) LaGuardia High School (4) [Program: Visual Arts] Harvest Collegiate LaGuardia High School (2) [Program: Vocal] Manhattan Village Academy LaGuardia High School (1) [Program: Tech Theater] Manhattan Bridges Professional Performing Arts (3) Central Park East Art and Design High School (2) Orchard Collegiate Academy Talent Unlimited [Program: Drama] Urban Assembly Gateway School for Technology Talent Unlimited [Program: Musical Theater] Urban Assembly School for Performing Arts Gramercy Arts High School Urban Assembly Gateway for Technology Frank Sinatra School Urban Assembly for Green Careers New Design Humanities Preparatory Academy Stephen T. Mather Building Arts & Craftsmanship Law and Public Service Culinary Arts/Harry Truman High School Law, Advocacy & Community Justice (M14A) Note: In New York City, students in 8th Grade have three possible pathways for admissions to public high schools, and they may apply to schools in one, two or three of the categories described here: (1) “Academic” high schools (screened or unscreened) Each has its own criteria for selection, in addition to grades, state test scores and attendance records. -

Angela's Ashes a Memoir of a Childhood by Frank

Angela's Ashes A Memoir of a Childhood By Frank McCourt This book is dedicated to my brothers, Malachy, Michael, Alphonsus. I learn from you, I admire you and I love you. A c k n o w l e d g m e n t s This is a small hymn to an exaltation of women. R'lene Dahlberg fanned the embers. Lisa Schwarzbaum read early pages and encouraged me. Mary Breasted Smyth, elegant novelist herself, read the first third and passed it on to Molly Friedrich, who became my agent and thought that Nan Graham, Editor-in-Chief at Scribner, would be just the right person to put the book on the road. And Molly was right. My daughter, Maggie, has shown me how life can be a grand adventure, while exquisite moments with my granddaughter, Chiara, have helped me recall a small child's wonder. My wife, Ellen, listened while I read and cheered me to the final page. I am blessed among men. I My father and mother should have stayed in New York where they met and married and where I was born. Instead, they returned to Ireland when I was four, my brother, Malachy, three, the twins, Oliver and Eugene, barely one, and my sister, Margaret, dead and gone. When I look back on my childhood I wonder how I survived at all. It was, of course, a miserable childhood: the happy childhood is hardly worth your while. Worse than the ordinary miserable childhood is the miserable Irish childhood, and worse yet is the miserable Irish Catholic childhood. -

Angela's Ashes

Angela’s Ashes Unit Plan Year 12 – Analyse extended written text(s) Duration: 4-5 weeks Strand: Written Language Sub-Strands: Reading Links with other strands: Close Reading; Exploring Language; Transactional Writing Achievement Objectives/Processes . Close Reading . Exploring Language . Thinking Critically . Transactional Writing (Levels 7-8) Learning Outcomes By the end of this unit, students should have read a novel and be able to: 1. Understand the make up of a novel; 2. understand and summarise the plot; 3. understand how setting and character are created; 4. understand the way the plot has been structured; 5. discuss and evaluate themes; 6. show an understanding of new ideas and vocabulary; 7. and write an essay answer about an aspect of the text Activities . Read novel . Quiz . Plot summary . Close reading task sheets . Discussion and notes on - setting - characterisation - themes - style . Written answers Resources . Class set of novel “Angela’s Ashes” by Frank McCourt . Unit plan as follows Assessment criteria English Curriculum Levels 7-8 NCEA Level 2, Achievement Standard 90377 (English 2.3) ‘Analyse extended written text(s)’. Achievement criteria Achievement Merit Excellence Analyse specified aspect(s) of Analyse specified aspect(s) of Analyse specified aspect(s) of extended written text(s) extended written text(s) extended written text(s) using supporting evidence. convincingly using supporting convincingly and with insight evidence. using supporting evidence. How Achievement Standard is assessed Achievement Standard is assessed by an eternal examination. Students are advised to spend 40 minutes on the exam paper. They are to answer only one of the questions. Pre-Reading Activities Post-box questions/discussion .