Tripura: Ethnic Conflict, Militancy and Counterinsurgency

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chapter 43 Electoral Statistics

CHAPTER 43 ELECTORAL STATISTICS 43.1 India is a constitutional democracy with a parliamentary system of government, and at the heart of the system is a commitment to hold regular, free and fair elections. These elections determine the composition of the Government, the membership of the two houses of parliament, the state and union territory legislative assemblies, and the Presidency and vice-presidency. Elections are conducted according to the constitutional provisions, supplemented by laws made by Parliament. The major laws are Representation of the People Act, 1950, which mainly deals with the preparation and revision of electoral rolls, the Representation of the People Act, 1951 which deals, in detail, with all aspects of conduct of elections and post election disputes. 43.2 The Election Commission of India is an autonomous, quasi-judiciary constitutional body of India. Its mission is to conduct free and fair elections in India. It was established on 25 January, 1950 under Article 324 of the Constitution of India. Since establishment of Election Commission of India, free and fair elections have been held at regular intervals as per the principles enshrined in the Constitution, Electoral Laws and System. The Constitution of India has vested in the Election Commission of India the superintendence, direction and control of the entire process for conduct of elections to Parliament and Legislature of every State and to the offices of President and Vice- President of India. The Election Commission is headed by the Chief Election Commissioner and other Election Commissioners. There was just one Chief Election Commissioner till October, 1989. In 1989, two Election Commissioners were appointed, but were removed again in January 1990. -

The Dignity of Santana Mondal

ISSN (Online) - 2349-8846 The Dignity of Santana Mondal VIJAY PRASHAD Vol. 49, Issue No. 20, 17 May, 2014 Vijay Prashad ([email protected]) is the Edward Said Chair at the American University of Beirut, Lebanon. Santana Mondal, a dalit woman supporter of the Communist Party of India (Marxist), was attacked by Trinamool Congress men for defying their diktat and exercising her franchise. This incident illustrates the nature of the large-scale violence which has marred the 2014 Lok Sabha elections in West Bengal. Serious allegations of booth capturing and voter intimidation have been levelled against the ruling TMC. Santana Mondal, a 35 year old woman, belongs to the Arambagh Lok Sabha parliamentary constituency in Hooghly district, West Bengal. She lives in Naskarpur with her two daughters and her sister Laxmima. The sisters work as agricultural labourers. Mondal and Laxmima are supporters of the Communist Party of India-Marxist [CPI(M)], whose candidate Sakti Mohan Malik is a sitting Member of Parliament (MP). Before voting took place in the Arambagh constituency on 30 April, political activists from the ruling Trinamool Congress (TMC) had reportedly threatened everyone in the area against voting for the Left Front, of which the CPI(M) is an integral part. Mondal ignored the threats. Her nephew Pradip also disregarded the intimidation and became a polling agent for the CPI(M) at one of the booths. After voting had taken place, three political activists of the TMC visited Mondal’s home. They wanted her nephew Pradip but could not find him there. On 6 May, two days later, the men returned. -

Social Media Stars:Kerala

SOCIAL MEDIA STARS: KERALA Two people whose reach goes beyond Kerala and its politics — Congress MP Shashi Tharoor and BJP’s surprise candidate for the Thiruvananthapuram Assembly constituency former cricketer S Sreesanth — lead the Twitter charts in the state. Chief Minister Oommen Chandy and BJP state president K Rajasekaran are also active, often tweeting in Malayalam. Due to long-standing alliances in the state, the United Democratic Front (UDF) led by the Congress has a handle of its own, in addition to independent handles of the parties. Neither the Left Front nor its leaders seem to have figured out Twitter. In the last of a four-part series on social media stars in the poll-bound states of Tamil Nadu, West Bengal, Assam and Kerala, N Sundaresha Subramanian looks at the Twitter scene in God’s Own Country OOMMEN CHANDY Chief Minister, Kerala (Congress) Twitter Handle: @Oommen_Chandy Tweets No. of followers 6,129 51.4K SHASHI THAROOR Congress MP, Thiruvananthapuram Twitter Handle: @ShashiTharoor S SREESANTH Tweets No. of followers BJP candidate, Thiruvananthapuram 30.8K 4.09M Twitter Handle: @sreesanth36 Tweets No. of followers 6,268 1.04M PARTY HANDLES UDF KERALA V MURALEEDHARAN Twitter Handle: @udfkerala BJP veteran Tweets No. of followers Twitter Handle: @MuraliBJP 103 4,602 Tweets No. of followers 625 4,415 CPI(M) KERALAM Twitter Handle: @CPIM_Keralam KUMMANAM RAJASEKHARAN Tweets No. of followers 4,127 State president, BJP 958 Twitter Handle: @Kummanam Tweets No. of followers BJP KERALAM 1,324 10.8K Twitter Handle: @BJP4Keralam Tweets No. of followers RAMESH 3,993 4,906 CHENNITHALA Home Minister , Kerala (Congress) Twitter Handle: @chennithala KERALA CONGRESS Tweets No. -

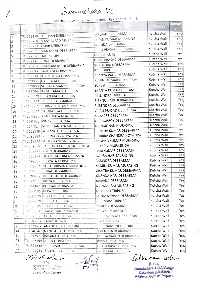

List of School Under South Tripura District

List of School under South Tripura District Sl No Block Name School Name School Management 1 BAGAFA WEST BAGAFA J.B SCHOOL State Govt. Managed 2 BAGAFA NAGDA PARA S.B State Govt. Managed 3 BAGAFA WEST BAGAFA H.S SCHOOL State Govt. Managed 4 BAGAFA UTTAR KANCHANNAGAR S.B SCHOOL State Govt. Managed 5 BAGAFA SANTI COL. S.B SCHOOL State Govt. Managed 6 BAGAFA BAGAFA ASRAM H.S SCHOOL State Govt. Managed 7 BAGAFA KALACHARA HIGH SCHOOL State Govt. Managed 8 BAGAFA PADMA MOHAN R.P. S.B SCHOOL State Govt. Managed 9 BAGAFA KHEMANANDATILLA J.B SCHOOL TTAADC Managed 10 BAGAFA KALA LOWGONG J.B SCHOOL TTAADC Managed 11 BAGAFA ISLAMIA QURANIA MADRASSA SPQEM MADRASSA 12 BAGAFA ASRAM COL. J.B SCHOOL State Govt. Managed 13 BAGAFA RADHA KISHORE GANJ S.B. State Govt. Managed 14 BAGAFA KAMANI DAS PARA J.B. SCHOOL State Govt. Managed 15 BAGAFA ASWINI TRIPURA PARA J.B SCHOOL State Govt. Managed 16 BAGAFA PURNAJOY R.P. J.B SCHOOL State Govt. Managed 17 BAGAFA GARDHANG S.B SCHOOL State Govt. Managed 18 BAGAFA PRATI PRASAD R.P. J.B SCHOOL TTAADC Managed 19 BAGAFA PASCHIM KATHALIACHARA J.B. State Govt. Managed 20 BAGAFA RAJ PRASAD CHOW. MEMORIAL HIGH SCHOOL State Govt. Managed 21 BAGAFA ALLOYCHARRA J.B SCHOOL TTAADC Managed 22 BAGAFA GANGARAI PARA J.B SCHOOL TTAADC Managed 23 BAGAFA KIRI CHANDRA PARA J.B SCHOOL TTAADC Managed 24 BAGAFA TAUCHRAICHA CHOW PARA J.B TTAADC Managed 25 BAGAFA TWIKORMO HS SCHOOL State Govt. Managed 26 BAGAFA GANGARAI S.B SCHOOL State Govt. -

India Freedom Fighters' Organisation

A Guide to the Microfiche Edition of Political Pamphlets from the Indian Subcontinent Part 5: Political Parties, Special Interest Groups, and Indian Internal Politics UNIVERSITY PUBLICATIONS OF AMERICA A Guide to the Microfiche Edition of POLITICAL PAMPHLETS FROM THE INDIAN SUBCONTINENT PART 5: POLITICAL PARTIES, SPECIAL INTEREST GROUPS, AND INDIAN INTERNAL POLITICS Editorial Adviser Granville Austin Guide compiled by Daniel Lewis A microfiche project of UNIVERSITY PUBLICATIONS OF AMERICA An Imprint of CIS 4520 East-West Highway • Bethesda, MD 20814-3389 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Indian political pamphlets [microform] microfiche Accompanied by printed guide. Includes bibliographical references. Content: pt. 1. Political Parties and Special Interest Groups—pt. 2. Indian Internal Politics—[etc.]—pt. 5. Political Parties, Special Interest Groups, and Indian Internal Politics ISBN 1-55655-829-5 (microfiche) 1. Political parties—India. I. UPA Academic Editions (Firm) JQ298.A1 I527 2000 <MicRR> 324.254—dc20 89-70560 CIP Copyright © 2000 by University Publications of America. All rights reserved. ISBN 1-55655-829-5. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction ............................................................................................................................. vii Source Note ............................................................................................................................. xi Reference Bibliography Series 1. Political Parties and Special Interest Groups Organization Accession # -

Memorandum of Settlement Between the Tripura State Government and All Tripura Tribal Force (ATTF)

Memorandum of Settlement between the Tripura State Government and All Tripura Tribal Force (ATTF) 23 August 1993 PREAMBLE: Where as the government of Tripura have been making concerned efforts to bring about an effective settlement of the problems of the tribal who are presently minority in Tripura an attempt have been made on a continuing basis to usher in peace and harmony in areas in which disturbed conditions have prevailed for long. AND Whereas All Tripura Tribal Force have given a clear indication that they would like to give up the path of armed struggle and would like to resume a normal life and they have decided to abandon the path of violence and to seek solutions to their problems within the framework of the Constitution of India and, therefore, they have responded positively to the appeals made by the Government of Tripura to join the mainstream and to help in the cause of building a prosperous Tripura AND Whereas on a series of discussions between the parties here to and based on such discussions it has been mutually agreed by and between the parties hereto that the FIRST ATTF shall give up the path of violence and surrender to the Other Party the Government of Tripura along with all their arms and ammunition ending their underground activities and the Governor of Tripura will provide some economic package and financial benefits and facilities hereafter provided 2. (B). Action is taken against foreign Nationals: - Action would be taken in respect of sending back all Bangladesh foreign nationals who have come to Tripura after 25 th March, 1971 and are not in possession of valid documents authorizing their presence in Tripura. -

Vicenç Fisas Vicenç Fisas Armengol (Barcelona, 1952) Is the Director of the School for a Culture of Peace at the Autonomous University of Barcelona

Peace diplomacies Negotiating in armed conflicts Vicenç Fisas Vicenç Fisas Armengol (Barcelona, 1952) is the director of the School for a Culture of Peace at the Autonomous University of Barcelona. He holds a doctorate in Peace Studies from the University of Bradford (UK) and won the National Human Rights Award in 1988. He is the author of more than 40 books on peace, conflicts, disarmament and peace processes. He has published the “Yearbook of Peace Processes” since 2006, and in the past two decades he has participated in some of these peace processes. (http://escolapau.uab.cat). School for a Culture of Peace PEACE DIPLOMACIES: NEGOTIATING IN ARMED CONFLICTS Vicenç Fisas Icaria Más Madera Peace diplomacies: Negotiating in armed conflicts To my mother and father, who gave me life, something too beautiful if it can be enjoyed in conditions of dignity, for anyone, no matter where they are, and on behalf of any idea, to think they have the right to deprive anyone of it. CONTENTS Introduction 11 I - Armed conflicts in the world today 15 II - When warriors visualise peace 29 III - Design and architecture of peace processes: Lessons learned since the crisis 39 Common options for the initial design of negotiations 39 Crisis situations in recent years 49 Proposals to redesign the methodology and actors after the crisis 80 The actors’ “tool kit”: 87 Final recommendations 96 IV – Roles in a peace process 99 V - Alternative diplomacies 111 VI – Appendixes 129 Conflicts and peace processes in recent years. 130 Peace agreements and ratification of -

2021081046.Pdf

Samuxchana Vc Biock Kutcha house beneficiary list under Kakraban PD Answe Father Category APSWANI DEBBARMA TR1153198 SUBHASH DEBBARMA Kutcha Wall Yes RATAN KUMAR MURASING TR1128768 MANGALPAD MURASING Kutcha Wall Yes TR1128773 AMAR DEBBARMA ANANDA DEBBARMA Kutcha Wall Yes GUU PRASAD DEBBARMA Yes TR1177025 |MANYA LAL DEBBARMA Kutcha Wall TR1177028 HALEM MIA MNOHAR ALI Kutcha Wal Yes GURU PRASAD DEBBARMA Kutcha Nall TR1212148 SUNIL DEBBARMA Yes SURENDRA DEBBARMA Yes TR1128767 CHANDRA MANI DEBBARMA Kutcha Wall TR1235047 SADHANI DEBBARMA RABI TRIPURA Kutcha Wall Yes Kutcha Wall Yes TR1212144 JOY MOHAN DEBBARMA ARANYA PADA DEBBARMA RUHINI KUMAR DEB8ARMA Kutcha Wall Yes 10 TR1279857 HARIPADA DEBBARMA 11 TRL279860 SURJAYA MANIK DEBBARMA SURESH DEBBARMA Kutcha Wall Yes SHANTA KUMAR TRIPURA Kutcha Wall Yes 12 TR1200564 KRISHNAMANI TRIPURA 1258729 BIRAN MANI TRIPURA MALINDRA TRIPURA Kutcha Wall Yes Kutcha Wall 14 TR1165123 SURESH DEBBARMA BISHNU HARI DEBBARMA Yes 128769 PURNA MOHAN DEBBARMA SURENDRA DEBBARMA Kutcha Wall 1246344 GOURANGA DEBBARMA GURU PRASAD DEBBARMA Kutcha Wali Yes 17 RL140 83 KANTI BALA NOATIA SAHADEB DEBBARMA Kutcha Wa!l Yes 18 290885 BINAY DEBBARMA HACHUBROY DEBBARMA Kutcha Wali Yes 77024 SUKHCHANDRA MURASING MANMOHAN MURASING Kutcha Wall es 20 T1188838 SUMANGAL DEBBARMA JAINTHA KUMAR DEBBARMA Kutcha Wall Yes 2 T290883 PURRNARAY NOYATIYA DURRBA CHANDRA NOYATIYA Kutcha Wall Yes 212143 SHUKURAN!MURASING KRISHNA KUMAR MURASING Kutcha Wall Yes 279859 BAISHAKH LAKKHI MURASINGH PATHRAI MURASINGH Kutcha Wall Yes 128771 PULIN DEBBARMA -

South-Indian Images of Gods and Goddesses

ASIA II MB- • ! 00/ CORNELL UNIVERSITY* LIBRARY Date Due >Sf{JviVre > -&h—2 RftPP )9 -Af v^r- tjy J A j£ **'lr *7 i !! in ^_ fc-£r Pg&diJBii'* Cornell University Library NB 1001.K92 South-indian images of gods and goddesse 3 1924 022 943 447 AGENTS FOR THE SALE OF MADRAS GOVERNMENT PUBLICATIONS. IN INDIA. A. G. Barraud & Co. (Late A. J. Combridge & Co.)> Madras. R. Cambrav & Co., Calcutta. E. M. Gopalakrishna Kone, Pudumantapam, Madura. Higginbothams (Ltd.), Mount Road, Madras. V. Kalyanarama Iyer & Co., Esplanade, Madras. G. C. Loganatham Brothers, Madras. S. Murthv & Co., Madras. G. A. Natesan & Co., Madras. The Superintendent, Nazair Kanun Hind Press, Allahabad. P. R. Rama Iyer & Co., Madras. D. B. Taraporevala Sons & Co., Bombay. Thacker & Co. (Ltd.), Bombay. Thacker, Spink & Co., Calcutta. S. Vas & Co., Madras. S.P.C.K. Press, Madras. IN THE UNITED KINGDOM. B. H. Blackwell, 50 and 51, Broad Street, Oxford. Constable & Co., 10, Orange Street, Leicester Square, London, W.C. Deighton, Bell & Co. (Ltd.), Cambridge. \ T. Fisher Unwin (Ltd.), j, Adelphi Terrace, London, W.C. Grindlay & Co., 54, Parliament Street, London, S.W. Kegan Paul, Trench, Trubner & Co. (Ltd.), 68—74, iCarter Lane, London, E.C. and 25, Museum Street, London, W.C. Henry S. King & Co., 65, Cornhill, London, E.C. X P. S. King & Son, 2 and 4, Great Smith Street, Westminster, London, S.W.- Luzac & Co., 46, Great Russell Street, London, W.C. B. Quaritch, 11, Grafton Street, New Bond Street, London, W. W. Thacker & Co.^f*Cre<d Lane, London, E.O? *' Oliver and Boyd, Tweeddale Court, Edinburgh. -

Political Parties in India

A M K RESOURCE WORLD GENERAL KNOWLEDGE www.amkresourceinfo.com Political Parties in India India has very diverse multi party political system. There are three types of political parties in Indiai.e. national parties (7), state recognized party (48) and unrecognized parties (1706). All the political parties which wish to contest local, state or national elections are required to be registered by the Election Commission of India (ECI). A recognized party enjoys privileges like reserved party symbol, free broadcast time on state run television and radio in the favour of party. Election commission asks to these national parties regarding the date of elections and receives inputs for the conduct of free and fair polls National Party: A registered party is recognised as a National Party only if it fulfils any one of the following three conditions: 1. If a party wins 2% of seats in the Lok Sabha (as of 2014, 11 seats) from at least 3 different States. 2. At a General Election to Lok Sabha or Legislative Assembly, the party polls 6% of votes in four States in addition to 4 Lok Sabha seats. 3. A party is recognised as a State Party in four or more States. The Indian political parties are categorized into two main types. National level parties and state level parties. National parties are political parties which, participate in different elections all over India. For example, Indian National Congress, Bhartiya Janata Party, Bahujan Samaj Party, Samajwadi Party, Communist Party of India, Communist Party of India (Marxist) and some other parties. State parties or regional parties are political parties which, participate in different elections but only within one 1 www.amkresourceinfo.com A M K RESOURCE WORLD GENERAL KNOWLEDGE state. -

Country Technical Note on Indigenous Peoples' Issues

Country Technical Note on Indigenous Peoples’ Issues Republic of India Country Technical Notes on Indigenous Peoples’ Issues REPUBLIC OF INDIA Submitted by: C.R Bijoy and Tiplut Nongbri Last updated: January 2013 Disclaimer The opinions expressed in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of the International Fund for Agricultural Development (IFAD). The designations employed and the presentation of material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of IFAD concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The designations ‗developed‘ and ‗developing‘ countries are intended for statistical convenience and do not necessarily express a judgment about the stage reached by a particular country or area in the development process. All rights reserved Table of Contents Country Technical Note on Indigenous Peoples‘ Issues – Republic of India ......................... 1 1.1 Definition .......................................................................................................... 1 1.2 The Scheduled Tribes ......................................................................................... 4 2. Status of scheduled tribes ...................................................................................... 9 2.1 Occupation ........................................................................................................ 9 2.2 Poverty .......................................................................................................... -

Gorkha Identity and Separate Statehood Movement by Dr

Global Journal of HUMAN-SOCIAL SCIENCE: D History Archaeology & Anthropology Volume 14 Issue 1 Version 1.0 Year 2014 Type: Double Blind Peer Reviewed International Research Journal Publisher: Global Journals Inc. (USA) Online ISSN: 2249-460x & Print ISSN: 0975-587X Gorkha Identity and Separate Statehood Movement By Dr. Anil Kumar Sarkar ABN Seal College, India Introduction- The present Darjeeling District was formed in 1866 where Kalimpong was transformed to the Darjeeling District. It is to be noted that during Bhutanese regime Kalimpong was within the Western Duars. After the Anglo-Bhutanese war 1866 Kalimpong was transferred to Darjeeling District and the western Duars was transferred to Jalpaiguri District of the undivided Bengal. Hence the Darjeeling District was formed with the ceded territories of Sikkim and Bhutan. From the very beginning both Darjeeling and Western Duars were treated excluded area. The population of the Darjeeling was Composed of Lepchas, Nepalis, and Bhotias etc. Mech- Rajvamsis are found in the Terai plain. Presently, Nepalese are the majority group of population. With the introduction of the plantation economy and developed agricultural system, the British administration encouraged Nepalese to Settle in Darjeeling District. It appears from the census Report of 1901 that 61% population of Darjeeling belonged to Nepali community. GJHSS-D Classification : FOR Code : 120103 Gorkha Identity and Separate Statehood Movement Strictly as per the compliance and regulations of: © 2014. Dr. Anil Kumar Sarkar. This is a research/review paper, distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution- Noncommercial 3.0 Unported License http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/), permitting all non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.