Stereotypes on Radio 1337

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Race, Housing and the Fight for Civil Rights in Los Angeles

RACE, HOUSING AND THE FIGHT FOR CIVIL RIGHTS IN LOS ANGELES Lesson Plan CONTENTS: 1. Overview 2. Central Historical Question 3. Extended Warm-Up 4. Historical Background 5. Map Activity 6. Historical Background 7. Map Activity 8. Discriminatory Housing Practices And School Segregation 9. Did They Get What They Wanted, But Lose What They Had? 10. Images 11. Maps 12. Citations 1. California Curriculum Content Standard, History/Social Science, 11th Grade: 11.10.2 — Examine and analyze the key events, policies, and court cases in the evolution of civil rights, including Dred Scott v. Sandford, Plessy v. Ferguson, Brown v. Board of Education, Regents of the University of California v. Bakke, and California Proposition 209. 11.10.4 — Examine the roles of civil rights advocates (e.g., A. Philip Randolph, Martin Luther King, Jr., Malcolm X, Thurgood Marshall, James Farmer, Rosa Parks), including the significance of Martin Luther King, Jr. ‘s “Letter from Birmingham Jail” and “I Have a Dream” speech. 3 2. CENTRAL HISTORICAL QUESTION: Considering issues of race, housing, and the struggle for civil rights in post-World War II Los Angeles, how valid is the statement from some in the African American community looking back: “We got what we wanted, but we lost what we had”? Before WWII: • 1940s and 1950s - Segregation in housing. • Shelley v. Kraemer, 1948 and Barrows vs. Jackson, 1953 – U.S. Supreme Court decisions abolish. • Map activities - Internet-based research on the geographic and demographic movements of the African American community in Los Angeles. • Locating homes of prominent African Americans. • Shift of African Americans away from central city to middle-class communities outside of the ghetto, resulting in a poorer and more segregated central city. -

Exposing Minstrelsy and Racial Representation Within American Tap Dance Performances of The

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Masks in Disguise: Exposing Minstrelsy and Racial Representation within American Tap Dance Performances of the Stage, Screen, and Sound Cartoon, 1900-1950 A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Culture and Performance by Brynn Wein Shiovitz 2016 © Copyright by Brynn Wein Shiovitz 2016 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Masks in Disguise: Exposing Minstrelsy and Racial Representation within American Tap Dance Performances of the Stage, Screen, and Sound Cartoon, 1900-1950 by Brynn Wein Shiovitz Doctor of Philosophy in Culture and Performance University of California, Los Angeles, 2016 Professor Susan Leigh Foster, Chair Masks in Disguise: Exposing Minstrelsy and Racial Representation within American Tap Dance Performances of the Stage, Screen, and Sound Cartoon, 1900-1950, looks at the many forms of masking at play in three pivotal, yet untheorized, tap dance performances of the twentieth century in order to expose how minstrelsy operates through various forms of masking. The three performances that I examine are: George M. Cohan’s production of Little Johnny ii Jones (1904), Eleanor Powell’s “Tribute to Bill Robinson” in Honolulu (1939), and Terry- Toons’ cartoon, “The Dancing Shoes” (1949). These performances share an obvious move away from the use of blackface makeup within a minstrel context, and a move towards the masked enjoyment in “black culture” as it contributes to the development of a uniquely American form of entertainment. In bringing these three disparate performances into dialogue I illuminate the many ways in which American entertainment has been built upon an Africanist aesthetic at the same time it has generally disparaged the black body. -

George P. Johnson Negro Film Collection LSC.1042

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/tf5s2006kz No online items George P. Johnson Negro Film Collection LSC.1042 Finding aid prepared by Hilda Bohem; machine-readable finding aid created by Caroline Cubé UCLA Library Special Collections Online finding aid last updated on 2020 November 2. Room A1713, Charles E. Young Research Library Box 951575 Los Angeles, CA 90095-1575 [email protected] URL: https://www.library.ucla.edu/special-collections George P. Johnson Negro Film LSC.1042 1 Collection LSC.1042 Contributing Institution: UCLA Library Special Collections Title: George P. Johnson Negro Film collection Identifier/Call Number: LSC.1042 Physical Description: 35.5 Linear Feet(71 boxes) Date (inclusive): 1916-1977 Abstract: George Perry Johnson (1885-1977) was a writer, producer, and distributor for the Lincoln Motion Picture Company (1916-23). After the company closed, he established and ran the Pacific Coast News Bureau for the dissemination of Negro news of national importance (1923-27). He started the Negro in film collection about the time he started working for Lincoln. The collection consists of newspaper clippings, photographs, publicity material, posters, correspondence, and business records related to early Black film companies, Black films, films with Black casts, and Black musicians, sports figures and entertainers. Stored off-site. All requests to access special collections material must be made in advance using the request button located on this page. Language of Material: English . Conditions Governing Access Open for research. All requests to access special collections materials must be made in advance using the request button located on this page. Portions of this collection are available on microfilm (12 reels) in UCLA Library Special Collections. -

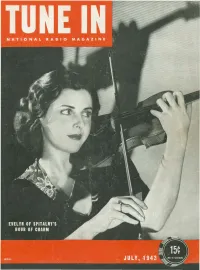

Tune in 4307.Pdf

ich co:mes first Your second helping? or our second front? OU \VANT TO SEE THIS 'VAll WDN - and ,,'on Yquickly. You want to see it carried to the encmy with a vengeance. Okay-so do all of us. But just remember... Cheerfully co-operating wit71 ration ing is one way we can help 'to win A sccond front takes food ... food to feed our this war. But there are scores of allies in addition to our own men. others. Many of them arc described in a new free booklet called uYou Which do you want - more meat for you, or and the 'War," available from this enough mcat for them? An extra cup of coffee on magazine. Send for your COPIJ to yOUl' breakfast table, or a full tin cup of coffee for day! Learn about the many oppor tunities for doing an important a fighting soldier? serdce to your country. Just remember that the meat you don't get Read about the Citizens Defense and the coffee and sugar that you don't get-are Corps, organized as part of Local up at the front lines-fighting for you. Defense Councils. Choose the tob f/ou're best at, and start doing it! Would you have it otherwise? You're needed-nowI Contrib"ted by Ihl! Maga~;ne PlJbli,her$ of America EVERY CIVILIAN A FIGHTER LETTERS TO THE EDITOR Get •..Ie WINtS MORE WINCHELL . str\g (:~ntlem{'n : \" I wal'! crazy al)('lUl th(> ;u'th"f> On Walter' Winchf'lI. whoge flJi:'ht for free l<llPech and aJeainflt It<olationism , ha\'e alwayl'l admir('f'), I 8PE' hI." has been in anothf"f fI!llollut(" with his reRgOTS ahout what he should say and what he shouldn't say, Why don't )'ou let us have thE" <1etalls of thl:;\ lat'-fiIt nght? There is noth· BORf\" I H20 ing so intE"restlng all a li::ood nght, especlall)' 1/111 I"m& 111'''''1 when a fellow you Ilk. -

Guide to the Joe Adams Papers

Guide to the Joe Adams Papers NMAH.AC.0908 Leah Blue 2008 Archives Center, National Museum of American History P.O. Box 37012 Suite 1100, MRC 601 Washington, D.C. 20013-7012 [email protected] http://americanhistory.si.edu/archives Table of Contents Collection Overview ........................................................................................................ 1 Administrative Information .............................................................................................. 1 Biographical / Historical.................................................................................................... 2 Arrangement..................................................................................................................... 4 Scope and Contents........................................................................................................ 3 Names and Subjects ...................................................................................................... 4 Container Listing ............................................................................................................. 5 Series 1: Photographs, 1947 - 1980........................................................................ 5 Series 2: Scrapbooks, circa 1947-1954................................................................... 7 Joe Adams Papers NMAH.AC.0908 Collection Overview Repository: Archives Center, National Museum of American History Title: Joe Adams Papers Identifier: NMAH.AC.0908 Date: 1948-1980 Creator: Adams, Joe, 1922- -

Black Representation in American Short Films, 1928-1954

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014 1-1-2002 Black representation in American short films, 1928-1954 Christopher P. Lehman University of Massachusetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_1 Recommended Citation Lehman, Christopher P., "Black representation in American short films, 1928-1954 " (2002). Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014. 914. https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_1/914 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014 by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. m UMASS. DATE DUE UNIVERSITY LIBRARY UNIVERSITY OF MASSACHUSETTS AMHERST BLACK REPRESENTATION IN AMERICAN ANIMATED SHORT FILMS, 1928-1954 A Dissertation Presented by CHRISTOPHER P. LEHMAN Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Massachusetts Amherst in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY May 2002 W. E. B. DuBois Department of Afro-American Studies © Copyright by Christopher P. Lehman 2002 All Rights Reserved BLACK REPRESENTATION IN AMERICAN ANIMATED SHORT FILMS, 1928-1954 A Dissertation Presented by CHRISTOPHER P. LEHMAN Approved as to style and content by: Ernest Allen, Chair Johnl|L Bracey, Jr., Member Robert P. Wolff, Member Lynda Morgan, Member Esther Terry, Department Head Afro-American Studies W. E. B. DuBois Department of ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Several archivists have enabled me to find sources for my research. I thank Tom Featherstone of Wayne State University's Walter Reuther Library for providing a copy of the film Brotherhood ofMan for me. -

Radio Drama: a "Visual Sound" Analysis of John, George and Drew Baby

University of Central Florida STARS Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 2012 Radio Drama: A "visual Sound" Analysis Of John, George And Drew Baby Pascha Weaver University of Central Florida Part of the Acting Commons Find similar works at: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd University of Central Florida Libraries http://library.ucf.edu This Masters Thesis (Open Access) is brought to you for free and open access by STARS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 by an authorized administrator of STARS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STARS Citation Weaver, Pascha, "Radio Drama: A "visual Sound" Analysis Of John, George And Drew Baby" (2012). Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019. 2168. https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd/2168 RADIO DRAMA: A “VISUAL SOUND” ANALYSIS OF JOHN, GEORGE AND DREW BABY by PASCHA WEAVER B.S. Florida Agricultural And Mechanical University, 1997 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Fine Arts in the Department of Theatre in the College of Arts and Humanities at the University of Central Florida Orlando, Florida Spring Term 2012 ©2012 Pascha L. Weaver ii ABSTRACT Radio Plays are a form of classic American Theatre that relies on dialogue, music and sound effects to audibly enhance a story with no visual component. While these types of plays are no longer at the forefront of modern day theatrical experience, I believe these popular plays of the mid-20th century are derivative of an oral storytelling tradition and significant to American entertainment culture. -

Racist Stereotypes in Tom and Jerry Bachelor’S Diploma Thesis

Masaryk University Faculty of Arts Department of English and American Studies English Language and Literature Martin Ondryáš Racist Stereotypes in Tom and Jerry Bachelor’s Diploma Thesis Supervisor: doc. PhDr. Tomáš Pospíšil, Ph.D. 2015 I declare that I have worked on this thesis independently, using only the primary and secondary sources listed in the bibliography. …………………………………………….. Martin Ondryáš I would like to thank doc. PhDr. Tomáš Pospíšil, Ph.D. for supervising my work, my parents for their support, Anna for being patient with my slow writing process and Zuzana for the faith she put in me. Table of Contents Introduction ............................................................................................................................. 6 1 Periodization and the Change of the Portrayal of African Americans in the Media ...... 8 2 Mammy ......................................................................................................................... 10 2.1 Origins of the Mammy Archetype ......................................................................... 11 2.2 Breaking the Archetype .......................................................................................... 13 2.3 Mammy Two Shoes ............................................................................................... 16 2.3.1 Mammy Two Shoes – A Maid or a House-owner? ........................................ 20 2.4 Jerry’s Disguise as a Mammy Stereotype (The Milky Waif) .................................. 21 2.5 Tom’s and Butch’s Disguises -

Lillian Randolph Born on December 14, 1898 Died September 12, 1980 Was an American Actress and Singer, a Veteran of Radio, Film, and Television

Lillian Randolph born on December 14, 1898 died September 12, 1980 was an American actress and singer, a veteran of radio, film, and television. She worked in entertainment from the 1930s well into the 1970s, ap- pearing in hundreds of radio shows, motion pictures, short subjects, and television shows. Born Castello Randolph in Knoxville, Tennessee, she was the younger sister of actress Amanda Randolph. The daughter of a Methodist minister and a teacher, she began her professional career singing on local radio in Cleveland, Ohio and Detroit, Michigan. At Detroit’s WXYZ, She was noticed by George W. Trendle, sta- tion owner and developer of The Lone Ranger and The Green Hornet. He got her into radio training courses which paid off in roles for local radio shows. Lillian was tutored for three months on “racial dialect” before getting any radio roles. She moved on to Los Angeles in 1936 to work on Al Jolson’s radio show, on Big Town, on the Al Pearce show, and to sing at the Club Alabam there. Though Lillian and her sister, Amanda, were continually looking for roles to make ends meet in 1938, she was gracious enough to open her home to Lena Horne, who was in California for her first movie role in The Duke Is Tops; the film was so tighly bud- geted, there was no money for a hotel for Horne. Lillian opened her home again during World War II with weekly dinners and entertainment for servicepeople in the Los Angeles area through American Women’s Voluntary Services (AWVS). -

IN FOCUS: African American Caucus

IN FOCUS: African American Caucus Introduction: When and Where We Enter by BERETTA E. SMITH-SHOMADE, RACQUEL GATES, and MIRIAM J. PETTY, editors “Don’t call it a comeback, I been here for years.” —LL Cool J, “Mama Said Knock You Out” (1990) “Wake up!” —Spike Lee, School Daze (1988) “Memory is a selection of images. Some elusive, others printed indelibly on the brain.” —Kasi Lemmons, Eve’s Bayou (1997) hen we fi rst began to assemble this In Focus on black media, our excitement was quickly tempered by the enormity of the undertaking.1 Should the essays focus on mainstream or in- dependent media? Would the contributors emphasize texts, pedagogy, or research? To what extent should we address issues of Widentity facing not only this type of scholarship but also the scholars themselves? Ultimately, we decided to take on all these questions, using Stuart Hall’s provocation “What Is This ‘Black’ in Black Popular Cul- ture?” as both prompt and connective thread. Written in 1992, Hall’s essay still carries particular resonance for this contemporary moment in media history. Hall makes it clear that issues of identity, represen- tation, and politics will always converge around blackness. Further, Hall’s own academic background reminds us that, as a fi eld, black media studies has always drawn on discourses and scholarship from multiple academic disciplines. This context is particularly important 1 We have chosen to use the term black when describing media texts and elements of popular culture and African American when referring to individuals and groups of people. In the essays that follow, however, the authors use these terms in many different ways. -

Physical Qualities

RADIO DRAMA: A “VISUAL SOUND” ANALYSIS OF JOHN, GEORGE AND DREW BABY by PASCHA WEAVER B.S. Florida Agricultural And Mechanical University, 1997 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Fine Arts in the Department of Theatre in the College of Arts and Humanities at the University of Central Florida Orlando, Florida Spring Term 2012 ©2012 Pascha L. Weaver ii ABSTRACT Radio Plays are a form of classic American Theatre that relies on dialogue, music and sound effects to audibly enhance a story with no visual component. While these types of plays are no longer at the forefront of modern day theatrical experience, I believe these popular plays of the mid-20th century are derivative of an oral storytelling tradition and significant to American entertainment culture. This thesis will discuss the aspects of radio plays that viscerally captured audiences. While this concept can be applied to many popular America radio shows of the time, this thesis will focus on one form ; the black radio play or black situation comedy series. I will deconstruct different genres of radio shows and identify the elements of sound effect, imagery and patterns in speech. This thesis will apply these elements to programs about white family life, (Fibber McGee and The Lone Ranger ) as well as family comedies about black cultural life, (Amos n' Andy, The Martin Lone and Beulah Show and Aunt Jemima). In addition, it will also reveal the business of employing white male actors to voice the parts of black characters and the physical mechanics used to create a “black sound”. -

Black Laughter / Black Protest: Civil Rights, Respectability, and The

©2008 Justin T. Lorts ALL RIGHTS RESERVED !!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!! Black Laughter / Black Protest: Civil Rights, Respectability, and the Cultural Politics of African American Comedy, 1934-1968 by Justin T. Lorts A Dissertation submitted to the Graduate School-New Brunswick Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Graduate Program in History written under the direction of Ann Fabian and approved by ________________________ ________________________ ________________________ ________________________ New Brunswick, New Jersey October 2008 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION ! Black Laughter / Black Protest: Civil Rights, Respectability, and the Cultural Politics of African American Comedy, 1934-1968 !by Justin T. Lorts !Dissertation Director: ! Ann Fabian ! Black Laughter / Black Protest explores the relationship between comedy and the modern civil rights movement. In the early years of the