Shabbat Table Talk Page

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Parashah 16 Beshalach

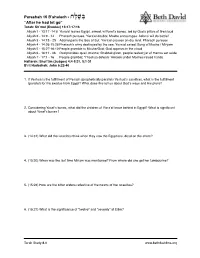

Parashah 16 B’shalach - jA;lAvV;b “After he had let go” Torah: Sh’mot (Exodus) 13:17-17:16 Aliyah 1 - 13:17 -14:8 Yisra’el leaves Egypt, armed, w/Yosef’s bones, led by God’s pillars of fire/cloud Aliyah 2 - 14:9 - 14 Pharaoh pursues, Yisra’el doubts; Moshe encourages: Adonai will do battle! Aliyah 3 - 14:15 - 25 Adonai parts the Sea of Suf, Yisra’el crosses on dry land, Pharaoh pursues Aliyah 4 - 14:26-15:26 Pharaoh’s army destroyed by the sea; Yisra’el saved; Song of Moshe / Miryam Aliyah 5 - 15:27-16:10 People grumble to Moshe/God; God appears in the cloud Aliyah 6 - 16:11 - 36 God provides quail, manna; Shabbat given, people rested; jar of manna set aside Aliyah 7 - 17:1 - 16 People grumble; Y’hoshua defeats ‘Amalek under Moshes raised hands Haftarah: Shof’tim (Judges) 4:4-5:31, 5:1-31 B’rit Hadashah: John 6:22-40 1. If Yeshua is the fulfillment of Pesach (prophetically parallels Yeshua’s sacrifice), what is the fulfillment (parallel) for the exodus from Egypt? What does this tell us about God’s ways and His plans? 2. Considering Yosef’s bones, what did the children of Yisra’el leave behind in Egypt? What is significant about Yosef’s bones? 3. (14:31) What did the Israelites think when they saw the Egyptians, dead on the shore? 4. (15:20) When was the last time Miriam was mentioned? From where did she get her tambourine? 5. (15:23) How are the bitter waters reflective of the hearts of the Israelites? 6. -

Parashah Mishpatim Jeremy Werbow Shabbat Shalom. “Moses Was Upon the Mountain Forty Days and Forty Nights”. the Number 40

Parashah Mishpatim Jeremy Werbow Shabbat Shalom. “Moses was upon the mountain forty days and forty nights”. The number 40 - what is it? The number is even - it can be divided by 2,4,5,8,10,20 and 40 - but what does 40 essentially signify? There are examples of the number 40 throughout daily life and the Torah. What may be considered the most well-known example in life of the number 40? The one that affects all people regardless of religion, color, race? Pregnancy. When a woman is pregnant she carries the baby in the womb for 40 weeks. Throughout the term of the pregnancy, many changes occur. When the egg is first fertilized, it is just one cell. Over the 40 weeks, a spinal cord, nerves, muscles, a torso, legs, and arms develop, along with all of the body’s organs. Throughout the term, all aspects of the baby grow and change. By the time the baby is born, it has changed from one single cell that weighed less than an ounce to 26 billion cells and weighs 8 pounds. At the same time as the baby is growing the woman is changing. Her body changes by adjusting to the new life within. She may have added some weight, show a baby bump, etc. She may also have emotional changes. Many women are more sensitive during their pregnancy than other times. Maybe she had other medical changes like gestational diabetes. Whatever changes a woman experiences, she will need to adjust to during this period in her life and again after the birth as her body returns to its “normal” state. -

The Two Screens: on Mary Douglas S Proposal

The Two Screens: On Mary Douglass Proposal for a Literary Structure to the Book of Leviticus* Gary A. Rendsburg In memoriam – Mary Douglas (1921–2007) In the middle volume of her recent trio of monographs devoted to the priestly source in the Torah, Mary Douglas proposes that the book of Leviticus bears a literary structure that reflects the layout and config- uration of the Tabernacle.1 This short note is intended to supply further support to this proposal, though first I present a brief summary of the work, its major suppositions, and its principal finding. The springboard for Douglass assertion is the famous discovery of Ramban2 (brought to the attention of modern scholars by Nahum Sar- na3) that the tripartite division of the Tabernacle reflects the similar tripartite division of Mount Sinai. As laid out in Exodus 19 and 24, (a) the people as a whole occupied the lower slopes; (b) Aaron, his two sons, and the elders were permitted halfway up the mountain; and (c) only Moses was allowed on the summit. In like fashion, according to the priestly instructions in Exodus 25–40 and the book of Leviticus, (a) the people as a whole were allowed to enter the outer court of the Taberna- * It was my distinct pleasure to deliver an oral version of this article at the Mary Douglas Seminar Series organized by the University of London in May 2005, in the presence of Professor Douglas and other distinguished colleagues. I also take the op- portunity to thank my colleague Azzan Yadin for his helpful comments on an earlier version of this article. -

Calendar of Torah and Haftarah Readings 5776 – 5778 2015 – 2018

Calendar of Torah and Haftarah Readings 5776 – 5778 2015 – 2018 Calendar of Torah and Haftarah Readings 5776-5778 CONTENTS NOTES ....................................................................................................1 DATES OF FESTIVALS .............................................................................2 CALENDAR OF TORAH AND HAFTARAH READINGS 5776-5778 ............3 GLOSSARY ........................................................................................... 29 PERSONAL NOTES ............................................................................... 31 Published by: The Movement for Reform Judaism Sternberg Centre for Judaism 80 East End Road London N3 2SY [email protected] www.reformjudaism.org.uk Copyright © 2015 Movement for Reform Judaism (Version 2) Calendar of Torah and Haftarah Readings 5776-5778 Notes: The Calendar of Torah readings follows a triennial cycle whereby in the first year of the cycle the reading is selected from the first part of the parashah, in the second year from the middle, and in the third year from the last part. Alternative selections are offered each shabbat: a shorter reading (around twenty verses) and a longer one (around thirty verses). The readings are a guide and congregations may choose to read more or less from within that part of the parashah. On certain special shabbatot, a special second (or exceptionally, third) scroll reading is read in addition to the week’s portion. Haftarah readings are chosen to parallel key elements in the section of the Torah being read and therefore vary from one year in the triennial cycle to the next. Some of the suggested haftarot are from taken from k’tuvim (Writings) rather than n’vi’ivm (Prophets). When this is the case the appropriate, adapted blessings can be found on page 245 of the MRJ siddur, Seder Ha-t’fillot. This calendar follows the Biblical definition of the length of festivals. -

Is There an Authentic Triennial Cycle of Torah Readings? RABBI LIONEL E

Is there an Authentic Triennial Cycle of Torah Readings? RABBI LIONEL E. MOSES This paper is an appendix to the paper "Annual and Triennial Systems For Reading The Torah" by Rabbi Elliot Dorff, and was approved together with it on April 29, 1987 by a vote of seven in favor, four opposed, and two abstaining. Members voting in favor: Rabbis Isidoro Aizenberg, Ben Zion Bergman, Elliot N. Dorff, Richard L. Eisenberg, Mayer E. Rabinowitz, Seymour Siegel and Gordon Tucker. Members voting in opposition: Rabbis David H. Lincoln, Lionel E. Moses, Joel Roth and Steven Saltzman. Members abstaining: Rabbis David M. Feldman and George Pollak. Abstract In light of questions addressed to the Committee on Jewish Law and Standards from as early as 1961 and the preliminary answers given to these queries by the committee (Section I), this paper endeavors to review the sources (Section II), both talmudic and post-talmudic (Section Ila) and manuscript lists of sedarim (Section lib) to set the triennial cycle in its historical perspective. Section III of the paper establishes a list of seven halakhic parameters, based on Mishnah and Tosefta,for the reading of the Torah. The parameters are limited to these two authentically Palestinian sources because all data for a triennial cycle is Palestinian in origin and predates even the earliest post-Geonic law codices. It would thus be unfair, to say nothing of impossible, to try to fit a Palestinian triennial reading cycle to halakhic parameters which were both later in origin and developed outside its geographical sphere of influence. Finally in Section IV, six questions are asked regarding the institution of a triennial cycle in our day and in a short postscript, several desiderata are listed in order to put such a cycle into practice today. -

Parashat Hashavua Curriculum Guidelines

1. Parashat Hashavua Curriculum Guidelines The JCP Parashat Hashavua Curriculum aims to provide a progressive teaching and learning structure where the weekly parashah is explored as a source of the mitzvot and middot according to which we live our lives as Jews. The curriculum explores social and moral issues and dilemmas relevant to children’s lives in the light of the actions of the Torah role models they encounter. The Parashat Hashavua Curriculum £ Is systematically developed throughout the school from Foundation Stage through to the end of Key Stage 2. £ Is developed SPIRALLY – where parashot are constantly revisited during the child’s progress throughout the school, and INCREMENTALLY – where skills are developed, knowledge built upon and concepts reinforced. £ Contains pesukim from the text to support and highlight the focus and/or middah/mitzvah. Pesukim should not be studied in depth. £ Is supported with commentaries (mainly Rashi) at appropriate levels. These commentaries must be clearly distinguished from the p’shat – literal meaning. £ Is supported with carefully selected traditional Midrashim to extend and amplify the text. Children should know that Midrash does not feature in the Chumash text. Midrashic interpretation should not obscure the main issues. £ Provides teachers with opportunities to employ a range of teaching approaches, access a variety of teaching material and create their own parallel and complementary resources. £ Provides opportunities to address PSHE by integrating the middah into an area of study. 2. Parashat Hashavua Unit Programmes of Study STORYLINE The emphasis needs to be on: • the personalities, main events and actions that feature in the weekly parashah and how they connect with each other • the relevant mitzvot and pertinent lessons that feature in the weekly parashah • the links that the weekly parashah contain to tefillah, the Jewish year and Jewish living. -

1 PARASHAH: Tol'dot (History) ADDRESS: B'resheet (Genesis) 25

PARASHAH: Tol’dot (History) ADDRESS: B’resheet (Genesis) 25:19-28:9 READING DATE: Shabbat AUTHOR: Torah Teacher Ariel ben-Lyman HaNaviy *Updated: November 26, 2005 (Note: all quotations are taken from the Complete Jewish Bible, translation by David H. Stern, Jewish New Testament Publications, Inc., unless otherwise noted) Let’s begin with the opening blessing for the Torah: “Baruch atah YHVH, Eloheynu, Melech ha-‘Olam, asher bachar banu m’kol ha-amim, v’natan lanu eht Torah-to. Baruch atah YHVH, noteyn ha-Torah. Ameyn.” (Blessed are you, O’ LORD, our God, King of the Universe, you have selected us from among all the peoples, and have given us your Torah. Blessed are you, LORD, giver of the Torah. Ameyn.) “Eyleh tol’dot…. (Here is the history [generations] of….).” These opening few words dot the beginnings of just a handful of significant chapters in the Torah. To be sure, there are ten significant instances in the book of B’resheet alone that use the Hebrew word “tol’dot,” which stems from the root word used for birth, or offspring. We read about the history of the heavens and the earth in Genesis 2:4; the history of Adam in 5:1; 6:9 and 10:1 talks about the history of Noach. Up until this point, the selection might appear rather “random,” that is, without pursuing a single family lineage. But after Noach, the Torah specifically begins narrowing down its selection of historical perspectives, singling out the significant person that is most pertinent for the reader’s study. After Noach’s listing in B’resheet 10:1, the Torah begins the pattern of tracing the lineage of a specific family history, highlighting the offspring of a specific man in particular. -

ELEVENTH MESSAGE: the SIN of NADAB and ABIHU PUNISHED with DEATH Leviticus 10:1-7 Introduction Right in the Midst of the Joyous

ELEVENTH MESSAGE: THE SIN OF NADAB AND ABIHU PUNISHED WITH DEATH Leviticus 10:1-7 Introduction Right in the midst of the joyous and moving experience that came when the priests officiated over their first fire-offerings, tragedy struck. The tragedy came because two of the priests, seemingly overenthusiastic over their new authority, misused that authority and offered an unauthorized offering. The two priests were Nadab and Abihu, the two oldest sons of Aaron. Their unauthorized offering could not be ignored, especially at the institution of the system of worship they were to supervise. Nadab and Abihu were struck dead for their offense. The punishment did not come without warning, because Moses on orders from Jehovah had told Aaron and his sons, “You must remain at the entrance to The Tent of Meeting day and night [for] seven days, and you shall watch the watch of Jehovah; and you will not die because thus I have been commanded” (Lev. 8:34). Aaron and his sons should have drawn two conclusions from those words: (1) The command did not originate with Moses, but came from God. (2) Any departure from God’s commands would result in death. Obviously, Nadab and Abihu were not listening carefully and proceeded to act according to their own ideas instead of God’s. In the very beginning of the service of the priests, the principle needed to be established that such actions could not be tolerated. Otherwise, all of the carefully constructed rituals of Israel that Jehovah had designed to teach divine truths would be corrupted and their meaning destroyed. -

Parasha 31: Emor (Speak/Say) Vayikra/Leviticus 21:1-24:23

Parasha 31: Emor (Speak/Say) Vayikra/Leviticus 21:1-24:23 *All Scripture References from The Orthodox Jewish Bible- Referred to as OJB- unless otherwise noted Joe Snipes (Torah Teacher) Gates To Zion Ministries Our parasha this week opens with YHWH ‘speaking’ to Aharon and his sons through Moshe. Before we go further, I want to take a moment to look at something interesting at the outset of our parasha. Speak And Say: Understanding The Inflection In writing there is sometimes an ‘unperceived handicap’. It is easy to miss getting the ‘nuances’ that help to ‘accentuate’ what is being read due to the ‘lack of inflection’ in the wording. In general, by speaking, we may ‘enhance’ what is being said by using ‘different tones of voice’ to convey the message. This is what we have here. The title of our parasha is ‘Emor’. It means, ‘to speak or say’. The important point is not only ‘what is said, but how it is said’. As usual, in the Torah, the title of the ‘parashot/portions’ come from the first few words. ‘Emor’ opens with YHWH ‘giving instruction’ through Moshe, “And Hashem [YHWH] said unto Moshe SPEAK unto the kohanim the Bnei Aharon [the priests the Sons of Aharon], and say unto them…” (Vayikra/Leviticus 21:1a OJB- emphasis/definitions mine) Before we go further, I want to take a moment to examine this word ‘emor/speak’. A little ‘closer look’ at this word in its ‘Hebraic setting’ will reveal there is something ‘very special’ about it. It is used ‘twenty times’ in our parasha alone! First, ‘emor’ is not the most ‘commonly used word’ in Hebrew when it comes to ‘speaking’ in the TaNaKh/Hebrew Scriptures, especially within the ‘Torah proper’. -

Transcript 73 Leviticus 10

The Naked Bible Podcast 2.0 Number 73 “Leviticus 10” Dr. Michael S. Heiser With Residential Layman Trey Stricklin November 1, 2015 Leviticus 10 Leviticus 10 describes the deaths of the priests Nadab and Abihu, the sons of Aaron, for offering “strange fire”. The nature of their transgression and other admonitions from God to the priesthood are discussed in this episode. TS: Welcome to the Naked Bible Podcast, Episode 73, Leviticus 10. I’m your layman, Trey Stricklin, and he’s the scholar, Dr. Michael Heiser. Hey Mike, how are you doing this week? MSH: Very good, glad to be back and to jump into Leviticus again. TS: I’m excited about Leviticus 10. We got some action on this one. MSH: I’ve actually heard from a few people that are enjoying Leviticus so I can’t diss it. I can’t diss it anymore. I got to get away from that. TS: There’s a lot to it that people don’t touch these types of books so I’m glad we’re doing it because somebody has to. MSH: Yeah, somebody has to. TS: I mean the first time I read it, you just don’t absorb it. You just kind of skim through it because it’s just so in-depth and it doesn’t apply. It’s just not practical so there’s a lot of people who just don’t focus on Leviticus more than just reading it and moving on. MSH: Yeah, I got to get through it so I can say I read the Bible. -

The King's Torah and the Torah's King רחא רבד | a Different Perspective

TORAH FROM JTS www.jtsa.edu/torah A Different Perspective | דבר אחר Limbs Gavriella Bernat-Kunin שופטים תשע"ז Alumna, Albert A. List College of Jewish Studies, ’17 Shofetim 5777 Limbs (2017) The King’s Torah and the Torah’s King Sharpie, colored pencil, Dr. Barry W. Holtz, Theodore and Florence Baumritter and acrylic on plexiglass Professor of Jewish Education at the William Davidson Graduate School of Jewish Education, JTS This work was created as This week’s Torah portion focuses on a wide array of topics, but underlying part of JTS’s artist-in- virtually everything we can see a thematic coherence well reflected in the residence program and is parashah’s name (“judges”). The sidrah contains one of the most famous lines in on display at JTS as part the entire Bible, tzedek, tzedek tirdof: “Justice, justice shall you pursue” (Deut. of the Corridors II 16:20). And throughout the parashah we see the Torah outlining various aspects exhibition. of the pursuit of justice. First is the establishment of courts, their organization and their authority. But the parashah has a larger vision than establishing the nature of the judiciary alone. Bernard M. Levinson, in his commentary on Deuteronomy in The Oxford Jewish Study Bible, points out “Although western political theory is normally traced back to ancient Athens, this section is remarkable for providing what seems to be the first blueprint for a constitutional system of government.” Over the course of this week’s reading the Torah presents a careful balance among four specific elements of power in ancient Israel: the judges, the priests, the prophets, and the king. -

Parashat Bereshit 5781

Parashat Bereshit 5781 Shabbat Shalom. Here we are, back at Bereshit, the first Parashah of the book that bears the same name, known in English as Genesis. This Parashah has some of the best known parts of the Torah. I’d like to offer some comments on the story of the Garden of Eden and Adam and Eve. First, it’s worth noting that this story which is so packed with memorable components, is rendered in so few verses. That’s part of the wonder of the Bible – how much it can pack into so few words. The Hebrew for the “Garden of Eden” is “Gan Eden” which literally means the “garden of pleasure." It later became the term used to refer to the afterlife in “Heaven.” People read the Bible and the Torah in many different ways. Some people read it very literally as though it were a history book. And though there are clearly historical elements in the Bible, reading it that way really misses the boat, in my opinion. Trying to find Gan Eden on a map is a terrible misreading. Seeing Gan Eden as an expression of the ideal of the human condition is much closer to the intent of the Torah. And that’s certainly how many Jewish thinkers have read it. If we look at the Hebrew names for Adam and Eve, we likewise see the much larger intentions of the story. Adam in Hebrew is a word for Human Being sharing a root with the word for “earth” adamah and the word for “blood” dam.