Accessing the Show Pointer

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Bedlington Terrier Club of America, Inc

1 The Bedlington Terrier Club of America, Inc The Bedlington Terrier Illustrated Breed Standard with Judges and Breeders Discussion 2 This Illustrated Breed Standard is dedicated to every student of the breed seeking knowledge for judging, breeding, showing or performance. We hope this gives you a springboard for your quest to understand this lovely and unusual terrier. Linda Freeman, Managing Editor Copyright, 2010 Bedlington Terrier Club of America, Inc. 3 Table of Contents Breed Standard………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………..4 History of the Breed………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………..5 General Appearance……………………………………………………………………………………………..…………………………………6 Head………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………..………7 Eyes…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………..…….8 Ears………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….9 Nose………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………..…….10 Jaws……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….10 Teeth……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………..………11 Neck and Shoulders……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….12 Body………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………12 Legs – Front…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….…………………….16 Legs – Rear……………………………………………………………………………………………..……………………………………………..17 Feet……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….18 Tail…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………18 Coat and Color……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….20 Height -

Dog Breeds Impounded in Fy16

DOG BREEDS IMPOUNDED IN FY16 AFFENPINSCHER 4 AFGHAN HOUND 1 AIREDALE TERR 2 AKITA 21 ALASK KLEE KAI 1 ALASK MALAMUTE 6 AM PIT BULL TER 166 AMER BULLDOG 150 AMER ESKIMO 12 AMER FOXHOUND 12 AMERICAN STAFF 52 ANATOL SHEPHERD 11 AUST CATTLE DOG 47 AUST KELPIE 1 AUST SHEPHERD 35 AUST TERRIER 4 BASENJI 12 BASSET HOUND 21 BEAGLE 107 BELG MALINOIS 21 BERNESE MTN DOG 3 BICHON FRISE 26 BLACK MOUTH CUR 23 BLACK/TAN HOUND 8 BLOODHOUND 8 BLUETICK HOUND 10 BORDER COLLIE 55 BORDER TERRIER 22 BOSTON TERRIER 30 BOXER 183 BOYKIN SPAN 1 BRITTANY 3 BRUSS GRIFFON 10 BULL TERR MIN 1 BULL TERRIER 20 BULLDOG 22 BULLMASTIFF 30 CAIRN TERRIER 55 CANAAN DOG 1 CANE CORSO 3 CATAHOULA 26 CAVALIER SPAN 2 CHESA BAY RETR 1 CHIHUAHUA LH 61 CHIHUAHUA SH 673 CHINESE CRESTED 4 CHINESE SHARPEI 38 CHOW CHOW 93 COCKER SPAN 61 COLLIE ROUGH 6 COLLIE SMOOTH 15 COTON DE TULEAR 2 DACHSHUND LH 8 DACHSHUND MIN 38 DACHSHUND STD 57 DACHSHUND WH 10 DALMATIAN 6 DANDIE DINMONT 1 DOBERMAN PINSCH 47 DOGO ARGENTINO 4 DOGUE DE BORDX 1 ENG BULLDOG 30 ENG COCKER SPAN 1 ENG FOXHOUND 5 ENG POINTER 1 ENG SPRNGR SPAN 2 FIELD SPANIEL 2 FINNISH SPITZ 3 FLAT COAT RETR 1 FOX TERR SMOOTH 10 FOX TERR WIRE 7 GERM SH POINT 11 GERM SHEPHERD 329 GLEN OF IMALL 1 GOLDEN RETR 56 GORDON SETTER 1 GR SWISS MTN 1 GREAT DANE 23 GREAT PYRENEES 6 GREYHOUND 8 HARRIER 7 HAVANESE 7 IBIZAN HOUND 2 IRISH SETTER 2 IRISH TERRIER 3 IRISH WOLFHOUND 1 ITAL GREYHOUND 9 JACK RUSS TERR 97 JAPANESE CHIN 4 JINDO 3 KEESHOND 1 LABRADOR RETR 845 LAKELAND TERR 18 LHASA APSO 61 MALTESE 81 MANCHESTER TERR 11 MASTIFF 37 MIN PINSCHER 81 NEWFOUNDLAND -

DOG BREEDS Affenpinscher Afghan Hound Airedale Terrier Akita

DOG BREEDS English Foxhound Polish Lowland English Setter Sheepdog Affenpinscher English Springer Pomeranian Afghan Hound Spaniel Poodle Airedale Terrier English Toy Spaniel Portuguese Water Dog Akita Field Spaniel Pug Alaskan Malamute Finnish Spitz Puli American Eskimo Dog Flat-Coated Retriever Rhodesian Ridgeback American Foxhound French Bulldog Rottweiler American Staffordshire German Pinscher Saint Bernard Terrier German Shepherd Dog Saluki American Water German Shorthaired Samoyed Spaniel Pointer Schipperke Anatolian Shepherd German Wirehaired Scottish Deerhound Dog Pointer Scottish Terrier Australian Cattle Dog Giant Schnauzer Sealyham Terrier Australian Shepherd Glen of Imaal Terrier Shetland Sheepdog Australian Terrier Golden Retriever Shiba Inu Basenji Gordon Setter Shih Tzu Basset Hound Great Dane Siberian Husky Beagle Great Pyrenees Silky Terrier Bearded Collie Greater Swiss Mountain Skye Terrier Beauceron Dog Smooth Fox Terrier Bedlington Terrier Greyhound Soft Coated Wheaten Belgian Malinois Harrier Terrier Belgian Sheepdog Havanese Spinone Italiano Belgian Tervuren Ibizan Hound Staffordshire Bull Bernese Mountain Dog Irish Setter Terrier Bichon Frise Irish Terrier Standard Schnauzer Black and Tan Irish Water Spaniel Sussex Spaniel Coonhound Irish Wolfhound Swedish Vallhund Black Russian Terrier Italian Greyhound Tibetan Mastiff Bloodhound Japanese Chin Tibetan Spaniel Border Collie Keeshond Tibetan Terrier Border Terrier Kerry Blue Terrier Toy Fox Terrier Borzoi Komondor Vizsla Boston Terrier Kuvasz Weimaraner Bouvier des -

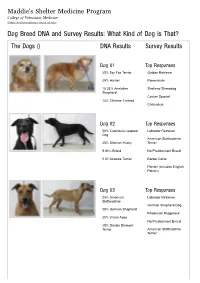

Dog Breed DNA and Survey Results: What Kind of Dog Is That? the Dogs () DNA Results Survey Results

Maddie's Shelter Medicine Program College of Veterinary Medicine (https://sheltermedicine.vetmed.ufl.edu) Dog Breed DNA and Survey Results: What Kind of Dog is That? The Dogs () DNA Results Survey Results Dog 01 Top Responses 25% Toy Fox Terrier Golden Retriever 25% Harrier Pomeranian 15.33% Anatolian Shetland Sheepdog Shepherd Cocker Spaniel 14% Chinese Crested Chihuahua Dog 02 Top Responses 50% Catahoula Leopard Labrador Retriever Dog American Staffordshire 25% Siberian Husky Terrier 9.94% Briard No Predominant Breed 5.07 Airedale Terrier Border Collie Pointer (includes English Pointer) Dog 03 Top Responses 25% American Labrador Retriever Staffordshire German Shepherd Dog 25% German Shepherd Rhodesian Ridgeback 25% Lhasa Apso No Predominant Breed 25% Dandie Dinmont Terrier American Staffordshire Terrier Dog 04 Top Responses 25% Border Collie Wheaten Terrier, Soft Coated 25% Tibetan Spaniel Bearded Collie 12.02% Catahoula Leopard Dog Briard 9.28% Shiba Inu Cairn Terrier Tibetan Terrier Dog 05 Top Responses 25% Miniature Pinscher Australian Cattle Dog 25% Great Pyrenees German Shorthaired Pointer 10.79% Afghan Hound Pointer (includes English 10.09% Nova Scotia Duck Pointer) Tolling Retriever Border Collie No Predominant Breed Dog 06 Top Responses 50% American Foxhound Beagle 50% Beagle Foxhound (including American, English, Treeing Walker Coonhound) Harrier Black and Tan Coonhound Pointer (includes English Pointer) Dog 07 Top Responses 25% Irish Water Spaniel Labrador Retriever 25% Siberian Husky American Staffordshire Terrier 25% Boston -

Baskerville Ultra Muzzle Breed Guide. Sizes Are Available in 1 - 6 and Are for Typical Adult Dogs & Bitches

Baskerville Ultra Muzzle Breed Guide. Sizes are available in 1 - 6 and are for typical adult dogs & bitches. Juveniles may need a size smaller. ‡ = not recommended. The number next to the breeds below is the recommended size. Boston Terrier ‡ Bulldog ‡ King Charles Spaniel ‡ Lhasa Apso ‡ Pekingese ‡ Pug ‡ St Bernard ‡ Shih Tzu ‡ Afghan Hound 5 Airedale 5 Alaskan Malamute 5 American Cocker 2 American Staffordshire 6 Australian Cattle Dog 3 Australian Shepherd 3 Basenji 2 Basset Hound 5 Beagle 3 Bearded Collie 3 Bedlington Terrier 2 Belgian Shepherd 5 Bernese MD 5 Bichon Frisé 1 Border Collie 3 Border Terrier 2 Borzoi 5 Bouvier 6 Boxer 6 Briard 5 Brittany Spaniel 5 Buhund 2 Bull Mastiff 6 Bull Terrier 5 Cairn Terrier 2 Cavalier Spaniel 2 Chow Chow 5 Chesapeake Bay Retriever 5 Cocker (English) 3 Corgi 3 Dachshund Miniature 1 Dachshund Standard 1 Dalmatian 4 Dobermann 5 Elkhound 4 English Setter 5 Flat Coated Retriever 5 Foxhound 5 Fox Terrier 2 German Shepherd 5 Golden Retriever 5 Gordon Setter 5 Great Dane 6 Greyhound 5 Hungarian Vizsla 3 Irish Setter 5 Irish Water Spaniel 3 Irish Wolfhound 6 Jack Russell 2 Japanese Akita 6 Keeshond 3 Kerry Blue Terrier 4 Labrador Retriever 5 Lakeland Terrier 2 Lurcher 5 Maltese Terrier 1 Maremma Sheepdog 5 Mastiff 6 Munsterlander 5 Newfoundland 6 Norfolk/Norwich Terrier 1 Old English Sheepdog 5 Papillon N/A Pharaoh Hound 5 Pit Bull 6 Pointers 4 Poodle Toy 1 Poodle Standard 3 Pyrenean MD 6 Ridgeback 5 Rottweiler 6 Rough Collie 3 Saluki 3 Samoyed 4 Schnauzer Miniature 2 Schnauzer 3 Schnauzer Giant 6 Scottish Terrier 3 Sheltie 2 Shiba Inu 2 Siberian Husky 5 Soft Coated Wheaten 4 Springer Spaniel 4 Staff Bull Terrier 6 Weimaraner 5 Welsh Terrier 3 West Highland White 2 Whippet 2 Yorkshire Terrier 1 . -

HOUND GROUP Photos Compliments of A.K.C

HOUND GROUP Photos Compliments of A.K.C. Wyoming 4-H AFGHAN HOUND HOUND Photos Compliments of A.K.C. Wyoming 4-H AMERICAN ENGLISH COONHOUND HOUND Photos Compliments of A.K.C. Wyoming 4-H AMERICAN FOXHOUND HOUND Photos Compliments of A.K.C. Wyoming 4-H AZAWAKH HOUND Photos Compliments of A.K.C. Wyoming 4-H BASENJI HOUND Photos Compliments of A.K.C. Wyoming 4-H BASSET HOUND HOUND Photos Compliments of A.K.C. Wyoming 4-H BEAGLE HOUND Photos Compliments of A.K.C. Wyoming 4-H BLACK AND TAN COONHOUND HOUND Photos Compliments of A.K.C. Wyoming 4-H BLOODHOUND HOUND Photos Compliments of A.K.C. Wyoming 4-H BLUETICK COONHOUND HOUND Photos Compliments of A.K.C. Wyoming 4-H BORZOI HOUND Photos Compliments of A.K.C. Wyoming 4-H CIRNECO DELL’ETNA HOUND Photos Compliments of A.K.C. Wyoming 4-H DACHSHUND HOUND Photos Compliments of A.K.C. Wyoming 4-H ENGLISH FOXHOUND HOUND Photos Compliments of A.K.C. Wyoming 4-H GRAND BASSET GRIFFON VENDEEN HOUND Photos Compliments of A.K.C. Wyoming 4-H GREYHOUND HOUND Photos Compliments of A.K.C. Wyoming 4-H HARRIER HOUND Photos Compliments of A.K.C. Photos Compliments of A.K.C. Wyoming 4-H IBIZAN HOUND HOUND Photos Compliments of A.K.C. Wyoming 4-H IRISH WOLFHOUND HOUND Photos Compliments of A.K.C. Wyoming 4-H NORWEGIAN ELKHOUND HOUND Photos Compliments of A.K.C. Wyoming 4-H OTTERHOUND HOUND Photos Compliments of A.K.C. -

The Book of the Otter

T H E B O O K O F TH E OTTER A MANUA L F OR SP OR TSM E N A ND NA TURA L/STS R I C H A R D C L A PH A M A UTH OR OF O! -HU TI G O T H E L AK LA D F LL S F N N N E N E , ” R OUG H SH O O T I NG ET , C . With I llus tra tio n s fro m Ph o tog raphs by the A u tho r F e s a nd Al red Ta lor . L e f y AND A N INTROD UCTION BY L L H I I A T PS . W M M O . M H O O N , H G N M H EAT RAN TO , L I I T E D 6 F LEET LA E L E . N , O N DO N , C 4 PREFA CE - is o ular I N these days otter hunting a p p sport , and in consequence there are now many more packs o f t otterhounds han was formerly the case . Of all o f o ne beasts chase in this country, the otter is the for about which we know least , he is a great O f th e wanderer , a creature night , and therefore f di ficult to study systematically . o Of the many pe ple who follow hounds , com arative l o r p yfew understand the science Of hunting , the habits o fthe creature which forms their quarry . -

Cultured Killers: Creating and Representing Foxhounds

Garry Marvin 1 Cultured Killers: Creating and Representing Foxhounds ABSTRACT This article concerns the related ideas of “presentation”and “rep- resentation”with regard to animals and suggests that the prefix “re”indicates a directing agent with its own concerns about the nature and status of animal presence. It further suggests that the representation of animals is perhaps always an expression of human concerns,desires, and imaginings. As with other domes- ticated nonhuman animals, foxhounds are not present in the world to fulfill their own purposes but there to fulfill these human desires and imaginings and are celebrated as the realization of a complex engagement of humans with the world of animals. The foxhound is central to English foxhunting and is given cultural meaning because of this context.The article offers a close anthro- pological interpretation of the production of this animal - a com- plex, cultural creation based on a canine form. Foxhounds are unusual nonhuman animals in terms of their relationships with both humans and other animals and in terms of the location and purposes of animals in English rural spaces. Hunting hounds have a unique existence poised between the worlds of humans and wild animals. Although a docile and domesticated dog, foxhounds are not companion ani- mals (“pets”) - animals created for close emotional relationships with individual humans. Nor, des- pite living in large groups in purpose-built animal Society & Animals 9:3 (2001) ©Koninklijke Brill NV, Leiden, 2001 shelters in r ural space, are they livestock - animals created for the exploita- tion of their bodies or bodily products. The Huntsman and his assistants have close, emotional, and enduring r elationships with the hounds, but such rela- tionships are not personalized into an individual pet relationship. -

Teaching News Is Elementary February 26, 2016

Teaching News Is Elementary February 26, 2016 Each week, this lesson will share some classroom activity ideas that use the newspaper or other NIE resources. You are encouraged to modify this lesson to fit the needs of your students. For example, some classrooms may be able to use this as a worksheet and others might need to ask and answer the questions in a class discussion. Materials you will need for this lesson: The Seattle Times e-Edition, colored pencils (drawing materials) and paper, access to or print outs from The American Kennel Club website Article: “Labrador retrievers top U.S. dog breed for 25 years” Page: Main News, A12 Date: Friday, February 23, 2016 Pre- Reading Discussion Questions: What makes a breed of dog “popular”? What kind of questions do you think will be answered in this article? For example, one question that the article might answer is “Why are Labrador retrievers the ‘top’ dog in the U.S.?”. What do you already know about dogs or Labradors that might help us understand what this article is about? Vocabulary: Read the following quotes and determine the meaning of the word based on how it’s used in the sentence: “Labrador retrievers still reign supreme after a quarter century as America’s most prevalent purebred dog.” To reign: to rule or be in control Prevalent: to be usual or widespread; common Purebred: bred from members of a recognized breed, strain, or kind without cross-breeding over many generations “French bulldogs moved from No. 9 to No. 6 last year and became the predominant purebred in Miami and San Francisco, having already conquered New York City.” Predominant: greater in influence, strength, or authority; main or leading “The droll little bat-eared bulldogs last peaked at No. -

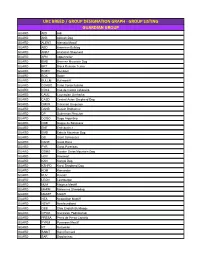

Ukc Breed / Group Designation Graph

UKC BREED / GROUP DESIGNATION GRAPH - GROUP LISTING GUARDIAN GROUP GUARD AIDI Aidi GUARD AKB Akbash Dog GUARD ALENT Alentejo Mastiff GUARD ABD American Bulldog GUARD ANAT Anatolian Shepherd GUARD APN Appenzeller GUARD BMD Bernese Mountain Dog GUARD BRT Black Russian Terrier GUARD BOER Boerboel GUARD BOX Boxer GUARD BULLM Bullmastiff GUARD CORSO Cane Corso Italiano GUARD CDCL Cao de Castro Laboreiro GUARD CAUC Caucasian Ovcharka GUARD CASD Central Asian Shepherd Dog GUARD CMUR Cimarron Uruguayo GUARD DANB Danish Broholmer GUARD DP Doberman Pinscher GUARD DOGO Dogo Argentino GUARD DDB Dogue de Bordeaux GUARD ENT Entlebucher GUARD EMD Estrela Mountain Dog GUARD GS Giant Schnauzer GUARD DANE Great Dane GUARD PYR Great Pyrenees GUARD GSMD Greater Swiss Mountain Dog GUARD HOV Hovawart GUARD KAN Kangal Dog GUARD KSHPD Karst Shepherd Dog GUARD KOM Komondor GUARD KUV Kuvasz GUARD LEON Leonberger GUARD MJM Majorca Mastiff GUARD MARM Maremma Sheepdog GUARD MASTF Mastiff GUARD NEA Neapolitan Mastiff GUARD NEWF Newfoundland GUARD OEB Olde English Bulldogge GUARD OPOD Owczarek Podhalanski GUARD PRESA Perro de Presa Canario GUARD PYRM Pyrenean Mastiff GUARD RT Rottweiler GUARD SAINT Saint Bernard GUARD SAR Sarplaninac GUARD SC Slovak Cuvac GUARD SMAST Spanish Mastiff GUARD SSCH Standard Schnauzer GUARD TM Tibetan Mastiff GUARD TJAK Tornjak GUARD TOSA Tosa Ken SCENTHOUND GROUP SCENT AD Alpine Dachsbracke SCENT B&T American Black & Tan Coonhound SCENT AF American Foxhound SCENT ALH American Leopard Hound SCENT AFVP Anglo-Francais de Petite Venerie SCENT -

Kurzform Rasse / Abbreviation Breed Stand/As Of: Sept

Kurzform Rasse / Abbreviation Breed Stand/as of: Sept. 2016 A AP Affenpinscher / Monkey Terrier AH Afghanischer Windhund / Afgan Hound AID Atlas Berghund / Atlas Mountain Dog (Aidi) AT Airedale Terrier AK Akita AM Alaskan Malamute DBR Alpenländische Dachsbracke / Alpine Basset Hound AA American Akita ACS American Cocker Spaniel / American Cocker Spaniel AFH Amerikanischer Fuchshund / American Foxhound AST American Staffordshire Terrier AWS Amerikanischer Wasserspaniel / American Water Spaniel AFPV Small French English Hound (Anglo-francais de petite venerie) APPS Appenzeller Sennenhund / Appenzell Mountain Dog ARIE Ariegeois / Arigie Hound ACD Australischer Treibhund / Australian Cattledog KELP Australian Kelpie ASH Australian Shepherd SILT Australian Silky Terrier STCD Australian Stumpy Tail Cattle Dog AUST Australischer Terrier / Australian Terrier AZ Azawakh B BARB Franzosicher Wasserhund / French Water Dog (Barbet) BAR Barsoi / Russian Wolfhound (Borzoi) BAJI Basenji BAN Basst Artesien Normad / Norman Artesien Basset (Basset artesien normand) BBG Blauer Basset der Gascogne / Bue Cascony Basset (Basset bleu de Gascogne) BFB Tawny Brittany Basset (Basset fauve de Bretagne) BASH Basset Hound BGS Bayrischer Gebirgsschweisshund / Bavarian Mountain Hound BG Beagle BH Beagle Harrier BC Bearded Collie BET Bedlington Terrier BBS Weisser Schweizer Schäferhund / White Swiss Shepherd Dog (Berger Blanc Suisse) BBC Beauceron (Berger de Beauce) BBR Briard (Berger de Brie) BPIC Picardieschäferhund / Picardy Shepdog (Berger de Picardie (Berger Picard)) -

American Foxhound: the State Dog of Virginia Good Citizen Lesson Plan

American Foxhound: The State Dog of Virginia Good Citizen Lesson Plan Curriculum: History and Social Science Grade: K-1 Virginia Standards of Learning: HSS.K.8, HSS.1.10, HSS.1.11 Objectives: Using pets to understand citizenship, students will be able to: • recognize the training and behavior for a pet to be a good citizen • identify the American Foxhound as the state dog of Virginia • compile a list of ways in which pets can be good or bad citizens • discuss, write, and draw about a specific topic Time Required: 60 minutes Materials and Resources: emblem picture of the American Foxhound; light-colored 8.5 x 11 inch paper or construction paper; crayons and markers; computer with Internet access; pet pictures from clip art, magazines, and/or personal images (printed and electronic, such as a JPEG); website www.petboogaloo.com/pet-award-certificate for computer made certificates; color printer. Procedure: 1. Discuss with students what it means to be a good citizen (e.g., following rules, respecting what belongs to others, taking responsibility for one’s own actions, helping others). 2. Hold up the emblem picture of the American Foxhound. Explain that the state dog of Virginia is the American Foxhound. 3. With the class looking at the emblem picture of the American Foxhound, ask them to compile a list of ways in which pets are good or bad citizens. Is it okay for a dog to growl, snarl, or jump up on visitors or to dig or go to the bathroom in a neighbor’s yard? Is it okay for an animal to wander the street? Wouldn’t it be nicer if a dog behaved in a friendly way towards visitors and was walked on a leash and kept in a fenced yard? 4.