Cultured Killers: Creating and Representing Foxhounds

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

FAO 2014. the Role, Impact and Welfare of Working (Traction And

5 FAO ANIMAL PRODUCTION AND HEALTH report THE ROLE, IMPACT AND WELFARE OF WORKING (TRACTION AND TRANSPORT) ANIMALS Report of the FAO - The Brooke Expert Meeting FAO Headquarters, Rome 13th – 17th June 2011 Cover photographs: Left image: ©FAO/Giuseppe Bizzarri Centre image: ©FAO/Giulio Napolitano Right image: ©FAO/Alessandra Benedetti 5 FAO ANIMAL PRODUCTION AND HEALTH report THE ROLE, IMPACT AND WELFARE OF WORKING (TRACTION AND TRANSPORT) ANIMALS Report of the FAO - The Brooke Expert Meeting FAO Headquarters, Rome 13th – 17th June 2011 Lisa van Dijk Bojia Endebu Duguma Mariano Hernández Gil Gisela Marcoppido Fred Ochieng Pit Schlechter Paul Starkey Chris Wanga Adroaldo Zanella FOOD AND AGRICULTURE ORGANIZATION OF THE UNITED NATIONS THE BROOKE HOSPITAL FOR ANIMALS Rome, 2014 Recommended Citation FAO. 2014. The role, impact and welfare of working (traction and transport) animals. Animal Production and Health Report. No. 5. Rome. The designations employed and the presentation of material in this information product do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) concerning the legal or development status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The mention of specific companies or products of manufacturers, whether or not these have been patented, does not imply that these have been endorsed or recommended by FAO in preference to others of a similar nature that are not mentioned. The views expressed in this information product are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of FAO. -

Animal Welfare

57227 Rules and Regulations Federal Register Vol. 78, No. 181 Wednesday, September 18, 2013 This section of the FEDERAL REGISTER and be exempt from the licensing and requirements and sets forth institutional contains regulatory documents having general inspection requirements if he or she responsibilities for regulated parties; applicability and legal effect, most of which sells only the offspring of those animals and part 3 contains specifications for are keyed to and codified in the Code of born and raised on his or her premises, the humane handling, care, treatment, Federal Regulations, which is published under for pets or exhibition. This exemption and transportation of animals covered 50 titles pursuant to 44 U.S.C. 1510. applies regardless of whether those by the AWA. The Code of Federal Regulations is sold by animals are sold at retail or wholesale. Part 2 requires most dealers to be the Superintendent of Documents. Prices of These actions are necessary so that all licensed by APHIS; classes of new books are listed in the first FEDERAL animals sold at retail for use as pets are individuals who are exempt from such REGISTER issue of each week. monitored for their health and humane licensing are listed in paragraph (a)(3) of treatment. § 2.1. DATES: Effective Date: November 18, Since the AWA regulations were DEPARTMENT OF AGRICULTURE 2013. issued, most retailers of pet animals have been exempt from licensing by FOR FURTHER INFORMATION CONTACT: Animal and Plant Health Inspection Dr. virtue of our considering them to be Service Gerald Rushin, Veterinary Medical ‘‘retail pet stores’’ as defined in § 1.1 of Officer, Animal Care, APHIS, 4700 River the AWA regulations. -

The Bedlington Terrier Club of America, Inc

1 The Bedlington Terrier Club of America, Inc The Bedlington Terrier Illustrated Breed Standard with Judges and Breeders Discussion 2 This Illustrated Breed Standard is dedicated to every student of the breed seeking knowledge for judging, breeding, showing or performance. We hope this gives you a springboard for your quest to understand this lovely and unusual terrier. Linda Freeman, Managing Editor Copyright, 2010 Bedlington Terrier Club of America, Inc. 3 Table of Contents Breed Standard………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………..4 History of the Breed………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………..5 General Appearance……………………………………………………………………………………………..…………………………………6 Head………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………..………7 Eyes…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………..…….8 Ears………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….9 Nose………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………..…….10 Jaws……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….10 Teeth……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………..………11 Neck and Shoulders……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….12 Body………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………12 Legs – Front…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….…………………….16 Legs – Rear……………………………………………………………………………………………..……………………………………………..17 Feet……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….18 Tail…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………18 Coat and Color……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….20 Height -

Dog Breeds of the World

Dog Breeds of the World Get your own copy of this book Visit: www.plexidors.com Call: 800-283-8045 Written by: Maria Sadowski PlexiDor Performance Pet Doors 4523 30th St West #E502 Bradenton, FL 34207 http://www.plexidors.com Dog Breeds of the World is written by Maria Sadowski Copyright @2015 by PlexiDor Performance Pet Doors Published in the United States of America August 2015 All rights reserved. No portion of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including photocopying, recording, or by any information retrieval and storage system without permission from PlexiDor Performance Pet Doors. Stock images from canstockphoto.com, istockphoto.com, and dreamstime.com Dog Breeds of the World It isn’t possible to put an exact number on the Does breed matter? dog breeds of the world, because many varieties can be recognized by one breed registration The breed matters to a certain extent. Many group but not by another. The World Canine people believe that dog breeds mostly have an Organization is the largest internationally impact on the outside of the dog, but through the accepted registry of dog breeds, and they have ages breeds have been created based on wanted more than 340 breeds. behaviors such as hunting and herding. Dog breeds aren’t scientifical classifications; they’re It is important to pick a dog that fits the family’s groupings based on similar characteristics of lifestyle. If you want a dog with a special look but appearance and behavior. Some breeds have the breed characterics seem difficult to handle you existed for thousands of years, and others are fairly might want to look for a mixed breed dog. -

Hazards: Animal Handling and Farm Structures

MODULE SIX Hazards: Animal Handling and Farm Structures Learning Objective: Upon completion of this unit you will be able to identify the hazards related to animal handling and farm structures on your operation and implement safety protocols to address these hazards. Learner Outcomes: You will be able to: 1. Identify and implement proper animal handling techniques. 2. Identify OSHA requirements for floor holes, floor Slide 1: openings, stairs and handrails. 3. Explain safety considerations related to electrical energy. 4. Define "confined space" and "permit required confined space." Slide 2: 5. Explain lockout-tagout procedure. 6. Describe safety measures to be taken with manure storage and handling facilities, upright and horizontal Slide 3: silos, and grain bins. 7. Outline techniques for teaching employees about hazards in animal handling and farm structures. Slide 4: Hazards: Animal Handling and Farm Structures • Module 6 • 1 General Animal Handling Slide 5: Working in close contact with dairy cattle is a necessary part of any dairy operation. There are some important generalizations we can make about cattle that facilitate their handling: • Excited animals are harder to handle. If cattle become nervous or excited when being worked, stop and allow the animal 30 minutes for their heart rates to return to normal. • Cattle are generally color blind and have poor depth perception, thus they are very sensitive to contrast. Eliminate blind turns, dark shadows and swinging/ dangling items in their path to enable easier movement. • Loud noises, especially high pitched noises, frighten cattle. When cattle are moved quietly they remain more calm and easier to handle. • Cattle remember "bad" experiences and create associations from fear memories. -

AVMA Guidelines for the Depopulation of Animals: 2019 Edition

AVMA Guidelines for the Depopulation of Animals: 2019 Edition Members of the Panel on Animal Depopulation Steven Leary, DVM, DACLAM (Chair); Fidelis Pharmaceuticals, High Ridge, Missouri Raymond Anthony, PhD (Ethicist); University of Alaska Anchorage, Anchorage, Alaska Sharon Gwaltney-Brant, DVM, PhD, DABVT, DABT (Lead, Companion Animals Working Group); Veterinary Information Network, Mahomet, Illinois Samuel Cartner, DVM, PhD, DACLAM (Lead, Laboratory Animals Working Group); University of Alabama at Birmingham, Birmingham, Alabama Renee Dewell, DVM, MS (Lead, Bovine Working Group); Iowa State University, Ames, Iowa Patrick Webb, DVM (Lead, Swine Working Group); National Pork Board, Des Moines, Iowa Paul J. Plummer, DVM, DACVIM-LA (Lead, Small Ruminant Working Group); Iowa State University, Ames, Iowa Donald E. Hoenig, VMD (Lead, Poultry Working Group); American Humane Association, Belfast, Maine William Moyer, DVM, DACVSMR (Lead, Equine Working Group); Texas A&M University College of Veterinary Medicine, Billings, Montana Stephen A. Smith, DVM, PhD (Lead, Aquatics Working Group); Virginia-Maryland College of Veterinary Medicine, Blacksburg, Virginia Andrea Goodnight, DVM (Lead, Zoo and Wildlife Working Group); The Living Desert Zoo and Gardens, Palm Desert, California P. Gary Egrie, VMD (nonvoting observing member); USDA APHIS Veterinary Services, Riverdale, Maryland Axel Wolff, DVM, MS (nonvoting observing member); Office of Laboratory Animal Welfare (OLAW), Bethesda, Maryland AVMA Staff Consultants Cia L. Johnson, DVM, MS, MSc; Director, Animal Welfare Division Emily Patterson-Kane, PhD; Animal Welfare Scientist, Animal Welfare Division The following individuals contributed substantively through their participation in the Panel’s Working Groups, and their assistance is sincerely appreciated. Companion Animals—Yvonne Bellay, DVM, MS; Allan Drusys, DVM, MVPHMgt; William Folger, DVM, MS, DABVP; Stephanie Janeczko, DVM, MS, DABVP, CAWA; Ellie Karlsson, DVM, DACLAM; Michael R. -

Dog Breeds Impounded in Fy16

DOG BREEDS IMPOUNDED IN FY16 AFFENPINSCHER 4 AFGHAN HOUND 1 AIREDALE TERR 2 AKITA 21 ALASK KLEE KAI 1 ALASK MALAMUTE 6 AM PIT BULL TER 166 AMER BULLDOG 150 AMER ESKIMO 12 AMER FOXHOUND 12 AMERICAN STAFF 52 ANATOL SHEPHERD 11 AUST CATTLE DOG 47 AUST KELPIE 1 AUST SHEPHERD 35 AUST TERRIER 4 BASENJI 12 BASSET HOUND 21 BEAGLE 107 BELG MALINOIS 21 BERNESE MTN DOG 3 BICHON FRISE 26 BLACK MOUTH CUR 23 BLACK/TAN HOUND 8 BLOODHOUND 8 BLUETICK HOUND 10 BORDER COLLIE 55 BORDER TERRIER 22 BOSTON TERRIER 30 BOXER 183 BOYKIN SPAN 1 BRITTANY 3 BRUSS GRIFFON 10 BULL TERR MIN 1 BULL TERRIER 20 BULLDOG 22 BULLMASTIFF 30 CAIRN TERRIER 55 CANAAN DOG 1 CANE CORSO 3 CATAHOULA 26 CAVALIER SPAN 2 CHESA BAY RETR 1 CHIHUAHUA LH 61 CHIHUAHUA SH 673 CHINESE CRESTED 4 CHINESE SHARPEI 38 CHOW CHOW 93 COCKER SPAN 61 COLLIE ROUGH 6 COLLIE SMOOTH 15 COTON DE TULEAR 2 DACHSHUND LH 8 DACHSHUND MIN 38 DACHSHUND STD 57 DACHSHUND WH 10 DALMATIAN 6 DANDIE DINMONT 1 DOBERMAN PINSCH 47 DOGO ARGENTINO 4 DOGUE DE BORDX 1 ENG BULLDOG 30 ENG COCKER SPAN 1 ENG FOXHOUND 5 ENG POINTER 1 ENG SPRNGR SPAN 2 FIELD SPANIEL 2 FINNISH SPITZ 3 FLAT COAT RETR 1 FOX TERR SMOOTH 10 FOX TERR WIRE 7 GERM SH POINT 11 GERM SHEPHERD 329 GLEN OF IMALL 1 GOLDEN RETR 56 GORDON SETTER 1 GR SWISS MTN 1 GREAT DANE 23 GREAT PYRENEES 6 GREYHOUND 8 HARRIER 7 HAVANESE 7 IBIZAN HOUND 2 IRISH SETTER 2 IRISH TERRIER 3 IRISH WOLFHOUND 1 ITAL GREYHOUND 9 JACK RUSS TERR 97 JAPANESE CHIN 4 JINDO 3 KEESHOND 1 LABRADOR RETR 845 LAKELAND TERR 18 LHASA APSO 61 MALTESE 81 MANCHESTER TERR 11 MASTIFF 37 MIN PINSCHER 81 NEWFOUNDLAND -

Service Dogs for America [email protected] 920 Short St / PO Box 513 Jud, ND 58454

Jenny BrodKorb, Executive Director Great Plains Assistance Dogs Foundation dba 701.685.2242 Service Dogs for America [email protected] 920 Short St / PO Box 513 www.servicedogsforamerica.org Jud, ND 58454 HB 1230: Relating to the definition of a service animal. _____ Thank you for your consideration regarding the language of North Dakota Century Code 25-13-01.1 regarding what animal can be considered a “service animal”. Under the current definition, it could be interpreted that a service animal could be “any animal” trained to do work, perform tasks, or provide assistance to an individual with a disability. Having North Dakota Century Code align with the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) removes confusion as to which animals specifically can be considered for service animal work. It should be clarified; a service animal by definition can only be a dog (or miniature horse, with limitations) defined by the ADA. It should also be clarified that a service animal MUST perform specific tasks to mitigate their hander’s disability/disabilities. I would recommend the following language: 25-13-01.1 Definitions: For the purpose of this chapter “service animal” means any dog (and sometimes miniature horse subject to limitations as defined by the ADA) that has been trained to do work, perform tasks, or provide assistance for the benefit of an individual with a disability. The tasks performed by the service animal must be directly related to the handler’s disability/disabilities. Animals whose sole function is to provide comfort, emotional support, or physical protection do not qualify as “service animals” under this definition. -

Advocating for Pit Bull Terriers: the Surprising Truths Revealed by the Latest Research – Ledy Vankavage

Advocating for Pit Bull Terriers: The Surprising Truths Revealed by the Latest Research – Ledy VanKavage Advoca'ng*for* Pit*Bull*Terriers* *A6orney*Fred*Kray,*Pit$Bulle)n$Legal$ News,*presen'ng*the*Wallace*Award* to*Lori*Weise,*Downtown*Dog*Rescue* No More Homeless Pets National Conference October 10-13, 2013 1 Advocating for Pit Bull Terriers: The Surprising Truths Revealed by the Latest Research – Ledy VanKavage Ledy%VanKavage,%Esq.% Sr.*Legisla've*A6orney* Past*Chair*of*American*Bar* Associa'on’s*TIPS’*Animal* Law*Commi6ee* [email protected]* Karma*at*Fight*Bust*BunKer*before*adop'on** * (photo*by*Lynn*Terry)* * No More Homeless Pets National Conference October 10-13, 2013 2 Advocating for Pit Bull Terriers: The Surprising Truths Revealed by the Latest Research – Ledy VanKavage Join%Voices%for%No%More%Homeless%Pets% * % * capwiz.com/besJriends* No More Homeless Pets National Conference October 10-13, 2013 3 Advocating for Pit Bull Terriers: The Surprising Truths Revealed by the Latest Research – Ledy VanKavage *“Pit*bull*terriers*have* been*trained*to*be* successful*therapy*dogs* with*developmentally* disabled*children.”* Jonny*Jus'ce,*a*former*VicK*dog,*is*now*a* model*for*a*Gund*stuffed*toy.* No More Homeless Pets National Conference October 10-13, 2013 4 Advocating for Pit Bull Terriers: The Surprising Truths Revealed by the Latest Research – Ledy VanKavage “Pit*bull*terriers*are*extremely* intelligent,*making*it*possible*for* them*to*serve*in*law*enforcement* and*drug*interdic'on,*as*therapy* dogs,*as*search*and*rescue*dogs,* -

Accessing the Show Pointer

ASSESSING THE SHOW POINTER by Wayne R. Cavanaugh Copyright 1997, Wayne R. Cavanaugh All right reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical or otherwise, including information storage and retrieval systems, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the author. Introduction This paper is intended as a guide to assessing the show Pointer. It is not intended to be the only guide that can help assess a Pointer, nor is it any substitution for looking at, seeing, living with, and shooting over a variety of really good dogs. It begins with an anatomical approach to history, followed by an interpretation of the standard and concludes with some general observations. The current American breed standard, (which is separately owned and copyrighted by the American Pointer Club, Inc.) is referenced in the Appendix. To expand your own base of reference, it is suggested that you also become familiar with the standard from the country of origin which in this case is considered, by the FCI at least, to be England. The late Bob Wehle of Elhew fame has also written his own breed standard that is a great read. At the end of the day, the important thing is to learn to see and understand all the parts, then hope they eventually all come into focus together. PART ONE AN ANATOMICAL APPROACH TO HISTORY AN ANATOMICAL APPROACH TO POINTER HISTORY The history of the Pointer, like many breeds, is a reasonably debatable topic. -

DOG BREEDS Affenpinscher Afghan Hound Airedale Terrier Akita

DOG BREEDS English Foxhound Polish Lowland English Setter Sheepdog Affenpinscher English Springer Pomeranian Afghan Hound Spaniel Poodle Airedale Terrier English Toy Spaniel Portuguese Water Dog Akita Field Spaniel Pug Alaskan Malamute Finnish Spitz Puli American Eskimo Dog Flat-Coated Retriever Rhodesian Ridgeback American Foxhound French Bulldog Rottweiler American Staffordshire German Pinscher Saint Bernard Terrier German Shepherd Dog Saluki American Water German Shorthaired Samoyed Spaniel Pointer Schipperke Anatolian Shepherd German Wirehaired Scottish Deerhound Dog Pointer Scottish Terrier Australian Cattle Dog Giant Schnauzer Sealyham Terrier Australian Shepherd Glen of Imaal Terrier Shetland Sheepdog Australian Terrier Golden Retriever Shiba Inu Basenji Gordon Setter Shih Tzu Basset Hound Great Dane Siberian Husky Beagle Great Pyrenees Silky Terrier Bearded Collie Greater Swiss Mountain Skye Terrier Beauceron Dog Smooth Fox Terrier Bedlington Terrier Greyhound Soft Coated Wheaten Belgian Malinois Harrier Terrier Belgian Sheepdog Havanese Spinone Italiano Belgian Tervuren Ibizan Hound Staffordshire Bull Bernese Mountain Dog Irish Setter Terrier Bichon Frise Irish Terrier Standard Schnauzer Black and Tan Irish Water Spaniel Sussex Spaniel Coonhound Irish Wolfhound Swedish Vallhund Black Russian Terrier Italian Greyhound Tibetan Mastiff Bloodhound Japanese Chin Tibetan Spaniel Border Collie Keeshond Tibetan Terrier Border Terrier Kerry Blue Terrier Toy Fox Terrier Borzoi Komondor Vizsla Boston Terrier Kuvasz Weimaraner Bouvier des -

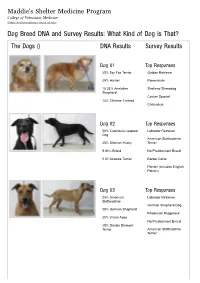

Dog Breed DNA and Survey Results: What Kind of Dog Is That? the Dogs () DNA Results Survey Results

Maddie's Shelter Medicine Program College of Veterinary Medicine (https://sheltermedicine.vetmed.ufl.edu) Dog Breed DNA and Survey Results: What Kind of Dog is That? The Dogs () DNA Results Survey Results Dog 01 Top Responses 25% Toy Fox Terrier Golden Retriever 25% Harrier Pomeranian 15.33% Anatolian Shetland Sheepdog Shepherd Cocker Spaniel 14% Chinese Crested Chihuahua Dog 02 Top Responses 50% Catahoula Leopard Labrador Retriever Dog American Staffordshire 25% Siberian Husky Terrier 9.94% Briard No Predominant Breed 5.07 Airedale Terrier Border Collie Pointer (includes English Pointer) Dog 03 Top Responses 25% American Labrador Retriever Staffordshire German Shepherd Dog 25% German Shepherd Rhodesian Ridgeback 25% Lhasa Apso No Predominant Breed 25% Dandie Dinmont Terrier American Staffordshire Terrier Dog 04 Top Responses 25% Border Collie Wheaten Terrier, Soft Coated 25% Tibetan Spaniel Bearded Collie 12.02% Catahoula Leopard Dog Briard 9.28% Shiba Inu Cairn Terrier Tibetan Terrier Dog 05 Top Responses 25% Miniature Pinscher Australian Cattle Dog 25% Great Pyrenees German Shorthaired Pointer 10.79% Afghan Hound Pointer (includes English 10.09% Nova Scotia Duck Pointer) Tolling Retriever Border Collie No Predominant Breed Dog 06 Top Responses 50% American Foxhound Beagle 50% Beagle Foxhound (including American, English, Treeing Walker Coonhound) Harrier Black and Tan Coonhound Pointer (includes English Pointer) Dog 07 Top Responses 25% Irish Water Spaniel Labrador Retriever 25% Siberian Husky American Staffordshire Terrier 25% Boston