The Flesch Readability Formula: Still Alive Or Still Life?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Reading 2050 Public Lecture Series 4

Reading 2050 a smart and sustainable city? Edited by Tim Dixon and Lorraine Farrelly School of the Built Environment University of Reading Public Lecture Series (2017–2019) Copyright: No part of this publication may be reproduced without the permission of the editors and the appropriate contributing author. This book has been developed in partnership with Barton Willmore and Reading UK. ii Contents Foreword 3 1 Introduction: The Reading 2050 Public Lecture Series 4 Part 1: Place and environment 2 Reading 2050 vision 8 3 Reading’s history and heritage 15 4 The Urban Room at the School of Architecture, University of Reading 19 5 The future of energy in Reading 22 6 The future of transport and mobility in Reading 27 7 Climate change and the zero carbon challenge in Reading 35 Part 2: People and lifestyle 8 Transforming the Museum of English Rural Life: past, present and future 41 9 Nature and people in our urban future 44 10 Measuring Reading’s resource consumption – an application of urban metabolism 48 Part 3: Economy and employment 11 Developing a Smart City Cluster in Thames Valley Berkshire 57 12 What Reading’s history teaches us about its ability to harness green technology to drive its future 61 13 The Future of Reading in the greater south east in a changing economic landscape 66 14 Delivering national growth, locally: the role of Thames Valley Berkshire LEP 72 15 What impact will population change, and other factors have on housing in Reading by 2050? 77 2 Foreword Imagine living in a city that is so smart and sustainable that it is The University of Reading has been part of the fabric of this place, a joy to live there. -

Local Wildife Sites West Berkshire - 2021

LOCAL WILDIFE SITES WEST BERKSHIRE - 2021 This list includes Local Wildlife Sites. Please contact TVERC for information on: • site location and boundary • area (ha) • designation date • last survey date • site description • notable and protected habitats and species recorded on site Site Code Site Name District Parish SU27Y01 Dean Stubbing Copse West Berkshire Council Lambourn SU27Z01 Baydon Hole West Berkshire Council Lambourn SU27Z02 Thornslait Plantation West Berkshire Council Lambourn SU28V04 Old Warren incl. Warren Wood West Berkshire Council Lambourn SU36D01 Ladys Wood West Berkshire Council Hungerford SU36E01 Cake Wood West Berkshire Council Hungerford SU36H02 Kiln Copse West Berkshire Council Hungerford SU36H03 Elm Copse/High Tree Copse West Berkshire Council Hungerford SU36M01 Anville's Copse West Berkshire Council Hungerford SU36M02 Great Sadler's Copse West Berkshire Council Inkpen SU36M07 Totterdown Copse West Berkshire Council Inkpen SU36M09 The Fens/Finch's Copse West Berkshire Council Inkpen SU36M15 Craven Road Field West Berkshire Council Inkpen SU36P01 Denford Farm West Berkshire Council Hungerford SU36P02 Denford Gate West Berkshire Council Kintbury SU36P03 Hungerford Park Triangle West Berkshire Council Hungerford SU36P04.1 Oaken Copse (east) West Berkshire Council Kintbury SU36P04.2 Oaken Copse (west) West Berkshire Council Kintbury SU36Q01 Summer Hill West Berkshire Council Combe SU36Q03 Sugglestone Down West Berkshire Council Combe SU36Q07 Park Wood West Berkshire Council Combe SU36R01 Inkpen and Walbury Hills West -

Vegetation Management Site Specification – Wokingham to Reading

Wessex Route CP6 Year 1 - Vegetation Management Site Specification – Wokingham to Reading 1. Site of Work Wokingham Station to Reading Station 2. Vegetation Management Overview The line of route between Wokingham and Reading is generally a heavily wooded urban area, which narrows in places and runs through a series of cuttings and embankments. Management of lineside vegetation between Wokingham and Reading has been overlooked in recent years and as a result, this route now tops Network Rail Wessex’s priority list for vegetation management. Lineside vegetation along this route is to be managed in order to prevent it causing obstruction and damage to either the rail network or to our lineside neighbours. In considering the work required, several criteria have been considered: • All lines of route must have a safe cess (walkway) for staff who are required to walk along the lineside to carry out their duties. A minimum 7 metre wide cut-back of vegetation has been specified in order to maintain a 6 metre wide vegetation-free corridor either side of the outermost rails. • Embankments supporting the railway tracks generally need vegetation to be retained at the bottom third of their slope in order to maintain stability at the toe of the embankment. In certain circumstances all vegetation is removed to allow for retaining structures to be installed. Where vegetation has the potential to cause an issue to Network Rail’s lineside neighbours it is to be removed. • There are several cutting slopes (where the railway is lower in elevation than the surrounding terrain) on the Wokingham to Reading route. -

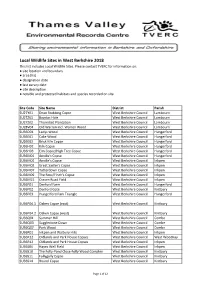

West Berks LWS and Plws List

Local Wildlife Sites in West Berkshire 2018 This list includes Local Wildlife Sites. Please contact TVERC for information on: ● site location and boundary ● area (ha) ● designation date ● last survey date ● site description ● notable and protected habitats and species recorded on site Site Code Site Name District Parish SU27Y01 Dean Stubbing Copse West Berkshire Council Lambourn SU27Z01 Baydon Hole West Berkshire Council Lambourn SU27Z02 Thornslait Plantation West Berkshire Council Lambourn SU28V04 Old Warren incl. Warren Wood West Berkshire Council Lambourn SU36D01 Ladys Wood West Berkshire Council Hungerford SU36E01 Cake Wood West Berkshire Council Hungerford SU36E02 Brick Kiln Copse West Berkshire Council Hungerford SU36H02 Kiln Copse West Berkshire Council Hungerford SU36H03 Elm Copse/High Tree Copse West Berkshire Council Hungerford SU36M01 Anville's Copse West Berkshire Council Hungerford SU36M01 Anville's Copse West Berkshire Council Inkpen SU36M02 Great Sadler's Copse West Berkshire Council Inkpen SU36M07 Totterdown Copse West Berkshire Council Inkpen SU36M09 The Fens/Finch's Copse West Berkshire Council Inkpen SU36M15 Craven Road Field West Berkshire Council Inkpen SU36P01 Denford Farm West Berkshire Council Hungerford SU36P02 Denford Gate West Berkshire Council Kintbury SU36P03 Hungerford Park Triangle West Berkshire Council Hungerford SU36P04.1 Oaken Copse (east) West Berkshire Council Kintbury SU36P04. -

Jealott's Hill, Warfield Technical Summary

JEALOTT’S HILL, WARFIELD TECHNICAL SUMMARY/OVERVIEW NOTE ON ECOLOGICAL CONSTRAINTS AND OPPORTUNITIES Executive Summary Development at the Jealott’s Hill site offers the opportunity to create extensive areas of new species and wildflower-rich mesotrophic grassland, through the reversion of arable land and through the diversification of existing improved grassland currently in agricultural use. Small patches of existing more diverse semi-improved grassland around the current research campus buildings could also form the basis of a significant project to create or restore new areas of ‘lowland meadow’ priority habitat; either through their retention and positive management in situ to promote enhancement, or through the use of the soil seed bank in these areas to diversify larger parts of the rural hinterland of the estate currently in agricultural use. Existing species-rich hedgerows can also be subject to positive future management using traditional conservation-friendly methods such as laying, with older hedgerows prioritised for retention within the layout, and new species-rich native hedgerows planted in conjunction with the proposals. Existing ponds can be subject to ecological restoration to improve their suitability for a range of species including aquatic invertebrates, amphibians, foraging bats and hunting Grass Snake. The habitats present both on site and in the wider area are likely to support a range of fauna of varying ecological importance including; amphibians, reptiles, breeding and overwintering birds (particularly farmland birds), mammals such as bats and Badgers, and invertebrate assemblages. The scale of the proposals and large areas of proposed Green Infrastructure being brought forward will provide the means to deliver new habitat for these species and this will be informed by further ecological survey work in due course. -

Phase 1 Ecological Surveys

SADPD SUPPORTING EVIDENCE Phase 1 Ecological Surveys John Wenman Ecological Consultancy June 2010 Phase 1 Ecological Survey Site Allocation Development Plan Document Bracknell Forest Borough Council Broad Area 1: SHLAA Sites within South West Sandhurst Ref: R70/b June 2010 100 New Wokingham Road, Crowthorne, Berkshire, RG45 6JP Telephone/Fax: 01344 780785 Mobile: 07979 403099 E-mail: [email protected] www.wenman-ecology.co.uk John Wenman Ecological Consultancy LLP is a limited liability partnership registered in England and Wales with registered number OC339057. Registered office: 100 New Wokingham Road, Crowthorne, Berkshire RG45 6JP where you may look at a list of members’ names. 1 SUMMARY........................................................................................................ 3 2 INTRODUCTION............................................................................................... 4 3 LEGISLATIVE BACKGROUND – PROTECTED SPECIES .............................. 6 4 POLICY BACKGROUND ................................................................................ 10 5 SURVEY METHOD ......................................................................................... 11 6 SURVEY FINDINGS........................................................................................ 12 7 DISCUSSION .................................................................................................. 19 8 RECOMMENDATIONS ................................................................................... 23 9 REFERENCES............................................................................................... -

Bracknell Forest

Landscape Character Area A1: Bracknell Forest Map 1: Location of Landscape Character Area A1 22 Image 1: Typical landscape of conifer plantation and new mixed broadleaf plantation on former heathland, with Round Hill in Crowthorne Wood in the middle distance, looking north from the Devil’s Highway at grid reference: 484936 164454. Location 5.3 This character area comprises a large expanse of forest plantation between the settlements of Bracknell to the north, Crowthorne and Sandhurst to the west, Camberley to the south (outside the study area within Surrey) and South Ascot to the east. The landscape continues into the Forested Settled Sands landscape type in Wokingham to the west and the Settled Wooded Sands in the Royal Borough of Windsor and Maidenhead to the east. Key Characteristics • Large areas of forestry plantation interspersed with broadleaf woodland and limited areas of open heath, giving a sense of enclosure and remoteness. • Typically short views, contained by trees, with occasional long views along historic, straight rides (such as the Devils’ Highway) and glimpsed views from more elevated areas. • A very low settlement density and few transport corridors. Suburban settlement and development related to light-industry occur at its peripheries, but these are mostly well screened by trees and not discernible from the interior. • Well-used recreation areas valued by the local community, including provisions for a range of formal recreational uses. • Despite the non-native land cover and presence of forestry operations the area has a sense of remoteness; a sense of removal from the surrounding urban settlements and a connection to the history of Windsor Forest. -

Bracknell Living List 2019

LOCAL WILDIFE SITES IN BRACKNELL FOREST - 2019 This list includes Local Widlife Sites. Please contact TVERC for information on: • site location and boundary • area (ha) • designation date • last survey date • site description • notable and protected habitats and species recorded on site Site Code Site Name District Parish SU87V13 Adj. Chavey Down Bracknell Forest Borough Council Winkfield SU86I01 Adj. Wokingham Road/Peacock Bracknell Forest Borough Council Bracknell Lane SU86Z03 Allsmoor Wood Bracknell Forest Borough Council Bracknell SU87V03 Beggars Roost/Adj. Strawberry Hill Bracknell Forest Borough Council Warfield SU87M04 Benham’s Copse Bracknell Forest Borough Council Binfield SU87V09 Big Wood Bracknell Forest Borough Council Warfield SU86U01 Bill Hill Bracknell Forest Borough Council Bracknell SU87K06 Binfield Hall Bracknell Forest Borough Council Binfield SU87K04 Binfield Manor Bracknell Forest Borough Council Binfield SU87K04 Binfield Manor Bracknell Forest Borough Council Warfield SU87K04 Binfield Manor Bracknell Forest Borough Council Binfield SU87K04 Binfield Manor Bracknell Forest Borough Council Binfield SU86P08 Blackman’s Copse Bracknell Forest Borough Council Binfield SU87Q11 Brickwork Meadows Bracknell Forest Borough Council Warfield SU86M01 Broadmoor Bottom (part) Bracknell Forest Borough Council Crowthorne SU87K02 Bryony Copse/Temple Copse Bracknell Forest Borough Council Binfield SU86M01 Butter Hill Bracknell Forest Borough Council Crowthorne SU87V23 Chavey Down Pond Bracknell Forest Borough Council Winkfield SU86F06 -

Directory of Mines and Quarries 2014

Directory of Mines and Quarries 2014 British Geological Survey Directory of Mines and Quarries, 2014 Tenth Edition Compiled by D G Cameron, T Bide, S F Parry, A S Parker and J M Mankelow With contributions by N J P Smith and T P Hackett Keywords Mines, Quarries, Minerals, Britain, Database, Wharfs, Rail Depots, Oilwells, Gaswells. Front cover Operations in the Welton Chalk at Melton Ross Quarry, Singleton Birch Ltd., near Brigg, North Lincolnshire. © D Cameron ISBN 978 0 85272 785-0 Bibliographical references Cameron, D G, Bide, T, Parry, S F, Parker, A S and Mankelow, J M. 2014. Directory of Mines and Quarries, 2014: 10th Edition. (Keyworth, Nottingham, British Geological Survey). © NERC 2014 Keyworth, Nottingham British Geological Survey 2014 BRITISH GEOLOGICAL SURVEY ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The full range of Survey publications is available from the BGS Sales The authors would like to acknowledge the assistance they have Desks at Nottingham, Edinburgh and London; see contact details received from the many organisations and individuals contacted below or shop online at www.geologyshop.com. The London Office during the compilation of this volume. In particular, thanks are due also maintains a reference collection of BGS publications including to our colleagues at BGS for their assistance during revisions of maps for consultation. The Survey publishes an annual catalogue of particular areas, the mineral planning officers at the various local its maps and other publications; this catalogue is available from any authorities, The Coal Authority, and to the many companies working of the BGS Sales Desks. in the Minerals Industry. The British Geological Survey carries out the geological survey of Great Britain and Northern Ireland (the latter is an agency EXCLUSION OF WARRANTY service for the government of Northern Ireland), and of the surrounding continental shelf, as well as its basic research Use by recipients of information provided by the BGS is at the projects. -

PRE-SUBMISSION DRAFT READING BOROUGH LOCAL PLAN Regulation 19 of the Town and Country Planning (Local Planning) (England) Regulations 2012

PRE-SUBMISSION DRAFT READING BOROUGH LOCAL PLAN Regulation 19 of the Town and Country Planning (Local Planning) (England) Regulations 2012 November 2017 DRAFT READING BOROUGH LOCAL PLAN ● APRIL 2017 FOREWORD FOREWORD By Councillor Tony Page The Local Plan will be the document that guides development in Reading up to 2036, and it will therefore play a decisive role in how our town evolves over the next two decades. We are publishing this draft of the plan for consultation, and it is important to have your views on it, so that they can be taken into account in finalising the plan. Over recent years, Reading has had considerable economic success, and this has resulted in considerable investment to the town. However, this success brings its own issues. In particular, Reading faces a housing crisis. There are not enough homes in general, and there is a particularly acute need for affordable housing, which represents more than half of our overall housing need. This document is a major part of our response to this issue, although we continue to work with neighbouring Councils to look at the needs of the Reading area as a whole. Other critical issues to be considered include how to provide the employment space and supporting infrastructure to make sure that Reading’s attractiveness as a place to work, to live and to study can continue. The benefits of Reading’s economic success also need to be shared out more equally with those communities in Reading that suffer high levels of deprivation and exclusion. The plan also looks again at the message that Reading’s environment sends to visitors and residents, both in terms of revitalising tired and run-down sites and areas, and in placing greater focus on our considerable, but often overlooked, historic legacy. -

Strategic Landscape & Visual Assessment

Central and Eastern Berkshire Joint Minerals & Waste Plan Strategic Landscape & Visual Assessment June 2018 Contents Executive Summary ................................................................................................... 2 1. Introduction .......................................................................................................... 6 2. Bracknell Forest Local Planning Authority Area ................................................... 8 Local Planning Policy .............................................................................................. 8 Landscape Character Assessment ......................................................................... 8 3. Wokingham Borough Council Local Planning Authority Area ............................ 14 Local Planning Policy ............................................................................................ 14 Landscape Character Assessment ....................................................................... 14 4. Windsor and Maidenhead Local Planning Authority Area .................................. 24 Local Planning Policy ............................................................................................ 25 Landscape Character Assessment ....................................................................... 25 Glossary of Terms………………………………………………………………………….65 Appendix 1: Landscape and Visual Impact Assessment Methodology..................... 63 Landscape Character Assessments .................................................................... -

End of Year Report April 2019 – March 2020

Thames Valley Environmental Records Centre END OF YEAR REPORT APRIL 2019 – MARCH 2020 End of Year Report 2019-20 CHAIR’S FOREWORD Each year in my foreword I reflect on the incredible number of records collected and maintained by the organisation, in 2019/20 we passed yet another milestone and now hold well over 3 million records which is a fantastic achievement. TVERC is once again at the heart of new developments in thinking about biodiversity nationally with the work which has been done to develop a help define a draft Nature Recovery Network for Oxfordshire. Given the ever-increasing pressures on the natural environment TVERC has been instrumental in helping local authorities in Berkshire to develop their policies by providing robust evidence base for developing their respective Local Plans. None of this work would be possible without TVERC’s dedicated staff who have provided an excellent service throughout this year whilst adapting seamlessly to the challenges of homeworking brought about by CV-19. It is with some regret that we will be saying goodbye to Camilla who has steered TVERC from a period of uncertainty when she started through a period of steady growth over the last few years. Camilla’s energy, enthusiasm and sense of humour will be missed by staff and members of the steering group alike. The planned separation from Oxfordshire County Council has sadly had to be postponed, in part due to the challenges caused by CV-19, but this also reflects changes in attitude at the host authority. Hopefully the next year will see the situation clarified within OCC and TVERC will be able to set off on a new more stable direction under the leadership of a new Director.