Royal Consort

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Divers Elegies, Set in Musick by Sev'rall Friends, Upon the Death

Divers Elegies, set in Musick by sev’rall Friends, upon the death of WILLIAM LAWES Edited by Jonathan P. Wainwright In association with Divers Elegies, set in Musick by sev’rall Friends, upon the death of William Lawes Edited by Jonathan P. Wainwright Page Introduction iii Editorial Notes vii Performance Notes viii Acknowledgements xii Elegiac texts on the death of William Lawes 1 ____________________ 1 Cease, O cease, you jolly Shepherds [SS/TT B bc] Henry Lawes 11 A Pastorall Elegie to the memory of my deare Brother William Lawes 2 O doe not now lament and cry [SS/TT B bc] John Wilson 14 An Elegie to the memory of his Friend and Fellow, M r. William Lawes, servant to his Majestie 3 But that, lov’d Friend, we have been taught [SSB bc] John Taylor 17 To the memory of his much respected Friend and Fellow, M r. William Lawes 4 Deare Will is dead [TTB bc] John Cobb 20 An Elegie on the death of his Friend and Fellow-servant, M r. William Lawes 5 Brave Spirit, art thou fled? [SS/TT B bc] Edmond Foster 24 To the memory of his Friend, M r. William Lawes 6 Lament and mourne, he’s dead and gone [SS/TT B bc] Simon Ives 25 An Elegie on the death of his deare fraternall Friend and Fellow, M r. William Lawes, servant to his Majesty 7 Why in this shade of night? [SS/TT B bc] John Jenkins 27 An Elegiack Dialogue on the sad losse of his much esteemed Friend, M r. -

Jouer Bach À La Harpe Moderne Proposition D’Une Méthode De Transcription De La Musique Pour Luth De Johann Sebastian Bach

JOUER BACH À LA HARPE MODERNE PROPOSITION D’UNE MÉTHODE DE TRANSCRIPTION DE LA MUSIQUE POUR LUTH DE JOHANN SEBASTIAN BACH MARIE CHABBEY MARA GALASSI LETIZIA BELMONDO 2020 https://doi.org/10.26039/XA8B-YJ76. 1. PRÉAMBULE ............................................................................................. 3 2. INTRODUCTION ......................................................................................... 5 3. TRANSCRIRE BACH À LA HARPE MODERNE, UN DÉFI DE TAILLE ................ 9 3.1 TRANSCRIRE OU ARRANGER ? PRÉCISIONS TERMINOLOGIQUES ....................................... 9 3.2 BACH TRANSCRIPTEUR ................................................................................................... 11 3.3 LA TRANSCRIPTION À LA HARPE ; UNE PRATIQUE SÉCULAIRE ......................................... 13 3.4 REPÈRES HISTORIQUES SUR LA TRANSCRIPTION ET LA RÉCEPTION DES ŒUVRES DE BACH AU FIL DES SIÈCLES ....................................................................................................... 15 3.4.1 Différences d’attitudes vis-à-vis de l’original ............................................................. 15 3.4.2 La musique de J.S. Bach à la harpe ............................................................................ 19 3.5 LES HARPES AU TEMPS DE J.S. BACH ............................................................................. 21 3.5.1 Panorama des harpes présentes en Allemagne. ......................................................... 21 4. CHOIX DE LA PIECE EN VUE D’UNE TRANSCRIPTION ............................... -

Considerations for Choosing and Combining Instruments

CONSIDERATIONS FOR CHOOSING AND COMBINING INSTRUMENTS IN BASSO CONTINUO GROUP AND OBBLIGATO INSTRUMENTAL FORCES FOR PERFORMANCE OF SELECTED SACRED CANTATAS OF JOHANN SEBASTIAN BACH Item Type text; Electronic Dissertation Authors Park, Chungwon Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 28/09/2021 04:28:57 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/194278 CONSIDERATIONS FOR CHOOSING AND COMBINING INSTRUMENTS IN BASSO CONTINUO GROUP AND OBBLIGATO INSTRUMENTAL FORCES FOR PERFORMANCE OF SELECTED SACRED CANTATAS OF JOHANN SEBASTIAN BACH by Chungwon Park ___________________________ Copyright © Chungwon Park 2010 A Document Submitted to the Faculty of the School of Music In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS In the Graduate College The UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 2010 2 UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA GRADUATE COLLEGE As members of the Document Committee, we certify that we have read the document prepared by Chungwon Park entitled Considerations for Choosing and Combining Instruments in Basso Continuo Group and Obbligato Instrumental Forces for Performance of Selected Sacred Cantatas of Johann Sebastian Bach and recommended that it be accepted as fulfilling the document requirement for the Degree of Doctor of Musical Arts _______________________________________________________Date: 5/15/2010 Bruce Chamberlain _______________________________________________________Date: 5/15/2010 Elizabeth Schauer _______________________________________________________Date: 5/15/2010 Thomas Cockrell Final approval and acceptance of this document is contingent upon the candidate’s submission of the final copies of the document to the Graduate College. -

Five Late Baroque Works for String Instruments Transcribed for Clarinet and Piano

Five Late Baroque Works for String Instruments Transcribed for Clarinet and Piano A Performance Edition with Commentary D.M.A. Document Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Musical Arts in the Graduate School of the The Ohio State University By Antoine Terrell Clark, M. M. Music Graduate Program The Ohio State University 2009 Document Committee: Approved By James Pyne, Co-Advisor ______________________ Co-Advisor Lois Rosow, Co-Advisor ______________________ Paul Robinson Co-Advisor Copyright by Antoine Terrell Clark 2009 Abstract Late Baroque works for string instruments are presented in performing editions for clarinet and piano: Giuseppe Tartini, Sonata in G Minor for Violin, and Violoncello or Harpsichord, op.1, no. 10, “Didone abbandonata”; Georg Philipp Telemann, Sonata in G Minor for Violin and Harpsichord, Twv 41:g1, and Sonata in D Major for Solo Viola da Gamba, Twv 40:1; Marin Marais, Les Folies d’ Espagne from Pièces de viole , Book 2; and Johann Sebastian Bach, Violoncello Suite No.1, BWV 1007. Understanding the capabilities of the string instruments is essential for sensitively translating the music to a clarinet idiom. Transcription issues confronted in creating this edition include matters of performance practice, range, notational inconsistencies in the sources, and instrumental idiom. ii Acknowledgements Special thanks is given to the following people for their assistance with my document: my doctoral committee members, Professors James Pyne, whose excellent clarinet instruction and knowledge enhanced my performance and interpretation of these works; Lois Rosow, whose patience, knowledge, and editorial wonders guided me in the creation of this document; and Paul Robinson and Robert Sorton, for helpful conversations about baroque music; Professor Kia-Hui Tan, for providing insight into baroque violin performance practice; David F. -

N E W S L E T T E R Vol

Harvard University Department of M usic MUSICn e w s l e t t e r Vol. 7, No. 1/Winter 2007 Out of Africa: Kay Kaufman Shelemay and the Music Building Ethiopian Diaspora North Yard ddis Ababa sprawls atop the Ethio- Harvard University pian highland plateau: lush with Cambridge, MA 02138 bougainvillea and eucalyptus, and Anoisy with merchants’ shouts from Africa’s 617-495-2791 largest outdoor market. More than four million people live here in the capital city, www.music.fas.harvard.edu where tin-roofed huts stand in extreme contrast to imperial palaces and elegant hotels. As a young graduate student, Kay INSIDE Kaufman Shelemay spent 2 1/2 years in Addis Ababa breathing in its colors, sounds, 3 Faculty News culture and people. Her book, A Song of INSIDE Shelemay recently interviewed Ethiopian masenqo player, Ato Getame- 4 Graduate Student News Longing. An Ethiopian Journey (1991) is at say Abebe in Cambridge. Left to right: Prof. Shelemay, Charles Sutton (who performed on the masenqo in Ethiopia), Getamesay Abebe, and 2 heart a love letter to this ancient, war-torn 5 Record 18 new graduate Harvard graduate student Danny Mekonnen. 3 part of Africa. students accepted 4 “I love Ethiopian music,” says Shelemay. “My York. This revolutionized my relationship to my 6 Alumni News dissertation project was on the liturgical music field—the work I was doing in Africa I could 6 Loeb Library donates of the Beta Israel, the community today known now do at home. It made me enormously aware of Ethiopian community around me.” materials to Tulane as the Ethiopian Jews, almost all of whom are now living in Israel. -

Richard Koprowski EDITORIAL BOARD

EDITOR: Richard Koprowski ASSOCIATE EDITOR: Douglass Seaton EDITORIAL BOARD: Thomas W. Baker, Laura DeMarco, Laurence Dreyfus, Paul Hawkshaw, Victoria Horn, Peter M. Lefferts, George Stauffer, Barbara Turchin EDITORIAL STAFF: Peter Dedel, James Bergin, Clara Kelly, Stephan Kotrch, Judith J. Mender, Dale E. ::Y1onson, Mary Lise Rheault, Martin H. Rutishauser, Lea M. Rutmanowitz, Glenn Stanley, Douglas A. Stumpf, Linda Williams ADJUNCT EDITORS: Nola Healy Lynch New York University Robert Lynch Rena 1\1 ueller BUSINESS DEPARTMENT: Ann Day FACULTY ADVISOR: Edward A. Lippman Copyright © 1977, The Trustees of Columbia University in the City of New York Printed in the United States CORRESPONDING EDITORS: Domestic Susan Gillerman Boston University, Boston, Mass. Carla Pollack Brandeis University, Waltham, Mass. Ellen Knight Brigham Young University, Provo, Utah Myrl Hermann Bryn Mawr College, Bryn Mawr, Pa. Harrison M. Schlee Carnegie-Mellon University, Pittsburgh, Pa. Kenneth Gabele Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland, Ohio Ronald T. Olexy Catholic University of America, Washington, D.C. John Gordon Morris City University of New York, New York, N.Y. Sheila Podolak City University of New York, Brooklyn College, Brooklyn, N.Y. Jeffrey Giles City University of New York, Hunter College, New York, N.Y. Monica Grabie City University of New York, Queens College, Flushing, N.Y. Edward Duffy Columbia University, New York, N.Y. Howard Pollack Cornell University, Ithaca, N.Y. Lou Reid Florida State University, Tallahassee, Fla. Susan Youens Harvard University, Cambridge, Mass. Robert A. Green Indiana University, Bloomington, Ind. Andrea Olmstead Juilliard School, New York, N.Y. William Borland Louisiana State University, Baton Rouge, La. Adriaan de Vries McGill University, Montreal, Quebec, Canada Laura Calzolari Manhattan School of Music, New York, N.Y. -

Richard Koprowski Douglass Seaton

EDITOR: Richard Koprowski ASSOCIATE EDITOR: Douglass Seaton EDITORIAL BOARD: Thomas W. Baker, Laura DeMarco, Laurence Dreyfus, Paul Hawkshaw, Victoria Horn, Peter M. Lefferts, George Stauffer, Barbara Turchin EDITORIAL ST AU: Judy Becker, James Bergin, Clara Kelly, Stephan Kotrch, Judith J. Dale E. :Vlonson, Lea M. Rutmanowitz, Glenn Stanley, Douglas A. Stumpf, Linda Williams ADJUNCT EDITORS: Asya Berger New York University Rena Mueller BUSINESS DEPARTMENT: Ann Day FACULTY ADVISOR: Leeman Perkins Copyright © 1977, The Trustees of Columbia University in the City of New York Printed in the United States CORRESPONDING EDITORS: Domestic Susan Gillerman Boston University, Boston, Mass. Brian Taylor Brandeis University, Waltham, Mass. Ellen Knight Brigham Young University, Provo, Utah Myrl Hermann Bryn Mawr College, Bryn Mawr, Pa. Harrison M. Schlee Carnegie· Mellon University, Pittsburgb, Pa. Kenneth Gabele Case 'Vestern Resene University, Cleveland, Ohio Ronald T. Olexy Catholic Uni\'ersity of America, Washington, D,C. John Gordon Morris City University of New York, New York, N.Y. Sheila Podolak City University of New York, Brooklyn College, Brooklyn, N.Y. Jeffrey Giles City University of New York, Hunter College, New York, N.Y. Monica Grable City University of New York, Queens College, Flushing, N.Y. Peter Lefferts Columbia University, New York, N.Y. Howard Pollack Cornell Uni\'ersity, Ithaca, N.Y. Lou Reid Florida State Unh'ersity, Tallahassee, Fla. Susan Youens Harvard University, Cambridge, Mass. Robert A. Green Indiana Uni\ersity, Bloomington, Ind. Andrea Olmstead Juilliard School, New York, ;\I.Y. William Borland Louisiana State University, Baton Rouge, La. Adriaan de Vries McGill University, Montreal, Quebec, Canada Laura Calzolarl Manhattan School of Music, New York, N.Y. -

Emma Kirkby Soprano Anthony Rooley Lute

THE UNIVERSITY MUSICAL SOCIETY OF THE UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN Emma Kirkby Soprano Anthony Rooley Lute THURSDAY EVENING, NOVEMBER 4, 1982, AT 8:30 RACKHAM AUDITORIUM, ANN ARBOR, MICHIGAN The English Orpheus A Contention between Hope and Despair ...................... JOHN DOWLAND Fantasia ............................................. ALFONSO FERRABOSCO Grief, keep within ........................................... JOHN DANYEL Pavan ....................................................... FERRABOSCO Thou Mighty God .............................................. DOWLAND Semper Dowland, semper dolens ................................. DOWLAND Sweet birds deprive us never ................................ JOHN BARTLETT INTERMISSION Come, shepherds come \ Perfect and endless circles are! ............................... WILLIAM LAWES Love I obey J I rise and grieve } The Lark J ..................................... HENRY LAWES A tale out of Anacreon j Stript of their green \ What a sad fate J .......................... HENRY PURCELL When first Amintas sued for a kiss) Mr. Rooley: London, Decca, Hyperion, and L'Oiseau Lyre Records. Miss Kirkby: Decca and Hyperion Records. Twelfth Concert of the 104th Season Special Concert About the Artists Anthony Rooley studied for three years at the Royal Academy of Music where his love of history and philosophy led him to study the music of the Renaissance. He owned his first lute in 1968 and later combined it with voice and viol to form The Consort of Musicke, one of today's leading specialist Renaissance ensembles. The ensemble covers all the major secular music of the period 1450-1650, with special emphasis in recent years on the English repertoire circa 1600. One major project to emanate from the Consort is a 21-record set of the "Complete Works of John Dowland," which has received accolades from critics throughout the world. In addition to the Consort, which is nearly a full-time concern, Mr. -

'Wagner and Literature: New Directions: Introduction'

This is a repository copy of 'Wagner and Literature: New Directions: Introduction'. White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/80544/ Version: Accepted Version Article: Allis, MJ (2014) 'Wagner and Literature: New Directions: Introduction'. Forum for Modern Language Studies. ISSN 0015-8518 https://doi.org/10.1093/fmls/cqu031 Reuse Unless indicated otherwise, fulltext items are protected by copyright with all rights reserved. The copyright exception in section 29 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 allows the making of a single copy solely for the purpose of non-commercial research or private study within the limits of fair dealing. The publisher or other rights-holder may allow further reproduction and re-use of this version - refer to the White Rose Research Online record for this item. Where records identify the publisher as the copyright holder, users can verify any specific terms of use on the publisher’s website. Takedown If you consider content in White Rose Research Online to be in breach of UK law, please notify us by emailing [email protected] including the URL of the record and the reason for the withdrawal request. [email protected] https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/ 1 Some late revisions made to this draft were subsequently incorporated at the publication stage. The final version is available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/fmls/cqu031 Wagner and Literature: New Directions Introduction Many readers of this Special Issue will be aware of the plethora of events last year marking the 200th anniversary of the birth of Richard Wagner (1813-83). -

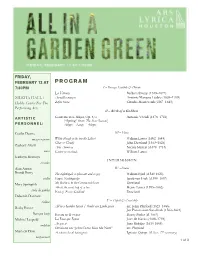

Garden Green Program Notes

FRIDAY, FEBRUARY 12 AT PROGRAM 7:30PM I – Breezes Earthly & Divine La Vittoria Barbara Strozzi (1619–1677) wfihe^=e^ii=L= Ayreçillos manços António Marques Lésbio (1639–1709) Hobby Center For The Zefiro torna Claudio Monteverdi (1567–1643) Performing Arts = II – Birth of a Goddess ARTISTIC Concerto in E Major, Op. 8/1 Antonio Vivaldi (1678–1741) (“Spring” from The Four Seasons) PERSONNEL: Allegro – Largo – Allegro Cecilia Duarte III – Flora mezzo-soprano White though ye be (on the Lilies) William Lawes (1602–1645) Clear or Cloudy John Dowland (1563–1626) Zachary Averyt Aria Amorosa Nicola Matteis (c1670–1714) tenor Gather ye rosebuds William Lawes Kathryn Montoya INTERMISSION recorder Alan Austin IV –Fauna Brandi Berry The nightingale so pleasant and so gay William Byrd (c1540-1623) violin Engels Nachtegaeltje Jacob van Eyck (c1590–1657) Mary Springfels My Robin is to the Greenwood Gone Dowland About the sweet bag of a bee Henry Lawes (1595–1662) viola da gamba Earl of Essex Gaillard Dowland Deborah Dunham violone V – Cupid & Courtship Becky Baxter All in a Garden Green / Onder een Linde groen arr. John Playford (1623–1686) Jan Pieterszoon Sweelinck (1562–1621) Baroque harp Sonata in G major Henry Butler (d. 1652) Michael Leopold La Rosa que Reyna Juan de Navas (c1650-1719) Ay que si Juan Hidalgo (1614-1685) archlute Divisions on “John Come Kiss Me Now” arr. Playford Matthew Dirst A señores los de buen gusto Ignacio Quispe (fl. late 17th century) harpsichord !1 of !3 PROGRAM NOTES Songs about spring have been around since the dawn of human history, when our ancestors first gave thanks for bright sunshine, warm breezes, gentle rain, and flowering plants. -

Jewish Secularity and Edgar Zilsel's Geniereligion

Yale Journal of Music & Religion Volume 6 Number 2 Sound and Secularity Article 2 2020 Assimilating to Art-Religion: Jewish Secularity and Edgar Zilsel’s Geniereligion (1918) Abigail Fine University of Oregon Follow this and additional works at: https://elischolar.library.yale.edu/yjmr Part of the Cultural History Commons, German Language and Literature Commons, Jewish Studies Commons, Musicology Commons, and the Other Religion Commons Recommended Citation Fine, Abigail (2020) "Assimilating to Art-Religion: Jewish Secularity and Edgar Zilsel’s Geniereligion (1918)," Yale Journal of Music & Religion: Vol. 6: No. 2, Article 2. DOI: https://doi.org/10.17132/2377-231X.1169 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by EliScholar – A Digital Platform for Scholarly Publishing at Yale. It has been accepted for inclusion in Yale Journal of Music & Religion by an authorized editor of EliScholar – A Digital Platform for Scholarly Publishing at Yale. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Assimilating to Art-Religion: Jewish Secularity and Edgar Zilsel’s Geniereligion (1918) Cover Page Footnote I wish to thank August Sheehy and Margarethe Adams for organizing the symposium that was the impetus for this project. This article was greatly enriched by incisive commentary from three anonymous reviewers who engaged with the work in detail. I am further indebted to Roy Chan for his thoughtful comments on a draft of this article. This article is available in Yale Journal of Music & Religion: https://elischolar.library.yale.edu/yjmr/vol6/iss2/2 Assimilating to Art-Religion Jewish Secularity and Edgar Zilsel’s Geniereligion (1918) Abigail Fine After fleeing the Nazis, many European From its first pages, Zilsel’s treatise set Jewish and Marxist scholars were fortunate out to destroy the Geniereligion—that is, the to find a new sense of belonging abroad, at parareligious cults of veneration that form institutions like the New School for Social around artists, scientists, pedagogues, and Research in New York City or among the other secular figures. -

An Examination of the Seventeenth-Century English Lyra

An examination of the seventeenth-century English lyra viol and the challenges of modern editing Volume 1 of 2 Volume 1 Katie Patricia Molloy MA by Research University of York Music January 2015 Abstract This dissertation explores the lyra viol and the issues of transcribing the repertoire for the classical guitar. It explores the ambiguities surrounding the lyra viol tradition, focusing on the organology of the instrument, the multiple variant tunings required to perform the repertoire, and the repertoire specifically looking at the solo works. The second focus is on the task of transcribing this repertoire, and specifically on how one can make it user-friendly for the 21st-century performer. It looks at the issues of tablature, and the issues of standard notation, and finally explores the notational possibilities with the transcription, experimenting with the different options and testing their accessibility. Volume II is a transliteration of solo lyra viol works by Simon Ives from the source Oxford, Bodleian Library Music School MS F.575. It includes a biography of Simon Ives, a study of the manuscript in question and describes the editorial procedures that were chosen as a result of the investigations in volume I. 2 Contents Volume I Abstract 2 Acknowledgements 6 Declaration 7 Introduction 8 1. The use of the term ‘lyra viol’ 12 2. The organology of the lyra viol 23 3. The tuning of the instrument 38 4. The lyra viol repertoire with specific focus on the solo works 45 5. The transcription of tablature 64 6. Experimentation with notation