Virtual Reality in Scripted Television: Why It Will Ultimately Fail

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Advances in Artificial Reality and Tele-Existence

R. Liang, Z. Pan, A. Cheok, M. Haller, R.W.H. Lau, H. Saito (Eds.) Advances in Artificial Reality and Tele-Existence 16th International Conference on Artificial Reality and Telexistence, ICAT 2006, Hangzhou, China, November 28 - December 1, 2006, Proceedings Series: Information Systems and Applications, incl. Internet/Web, and HCI, Vol. 4282 This book constitutes the refereed proceedings of the 16th International Conference on Artificial Reality and Telexistence, ICAT 2006, held in Hangzhou, China in November/ December 2006. The 138 revised full papers presented were carefully reviewed and selected from a total of 523 submissions. The papers are organized in topical sections on anthropomorphic intelligent robotics, artificial life, augmented reality, mixed reality, distributed and collaborative VR system, haptics, human factors of VR, innovative applications of VR, motion tracking, real time computer simulation, tools and technique for modeling VR systems, ubiquitous/wearable computing, virtual heritage, virtual medicine and health science, virtual reality, as well as VR interaction and navigation techniques. 2006, XLVI, 1350 p. In 2 volumes, not available separately. Printed book Softcover ▶ 159,99 € | £144.00 | $219.00 ▶ *171,19 € (D) | 175,99 € (A) | CHF 213.21 eBook Available from your bookstore or ▶ springer.com/shop MyCopy Printed eBook for just ▶ € | $ 24.99 ▶ springer.com/mycopy Order online at springer.com ▶ or for the Americas call (toll free) 1-800-SPRINGER ▶ or email us at: [email protected]. ▶ For outside the Americas call +49 (0) 6221-345-4301 ▶ or email us at: [email protected]. The first € price and the £ and $ price are net prices, subject to local VAT. Prices indicated with * include VAT for books; the €(D) includes 7% for Germany, the €(A) includes 10% for Austria. -

Evaluation of Virtual Reality Tracking Systems Underwater

International Conference on Artificial Reality and Telexistence Eurographics Symposium on Virtual Environments (2019) Y. Kakehi and A. Hiyama (Editors) Evaluation of Virtual Reality Tracking Systems Underwater Raphael Costa1,Rongkai Guo2,and John Quarles1 1University of Texas at San Antonio, USA 2Kennesaw State University, USA Abstract The objective of this research is to compare the effectiveness of various virtual reality tracking systems underwater. There have been few works in aquatic virtual reality (VR) - i.e., VR systems that can be used in a real underwater environment. Moreover, the works that have been done have noted limitations on tracking accuracy. Our initial test results suggest that inertial measurement units work well underwater for orientation tracking but a different approach is needed for position tracking. Towards this goal, we have waterproofed and evaluated several consumer tracking systems intended for gaming to determine the most effective approaches. First, we informally tested infrared systems and fiducial marker based systems, which demonstrated significant limitations of optical approaches. Next, we quantitatively compared inertial measurement units (IMU) and a magnetic tracking system both above water (as a baseline) and underwater. By comparing the devices’ rotation data, we have discovered that the magnetic tracking system implemented by the Razer Hydra is approximately as accurate underwater as compared to a phone-based IMU. This suggests that magnetic tracking systems should be further explored as a possibility -

Virtual and Augmented Reality Applications in Medicine And

OPEN ACCESS Freely available online iology: C ys ur h re P n t & R y e Anatomy & Physiology: s m e o a t r a c n h A ISSN: 2161-0940 Current Research Reie Article Virtual and Augmented Reality Applications in Medicine and Surgery- The Fantastic Voyage is here Wayne L Monsky1*, Ryan James2, Stephen S Seslar3 1Division of Interventional Radiology, Department of Radiology, University of Washington Medical Center, Washington, USA; 2Department of Biomedical Informatics and Medical Education, University of Washington, Seattle, Washington, USA; 3Division of Pediatric Cardiology, Department of Pediatrics, Seattle Children's Hospital, University of Washington, Seattle, WA, USA ABSTRACT Virtual Reality (VR), Augmented Reality (AR) and Head Mounted Displays (HMDs) are revolutionizing the way we view and interact with the world, affecting nearly every industry. These technologies are allowing 3D immersive display and understanding of anatomy never before possible. Medical applications are wide-reaching and affect every facet of medical care from learning gross anatomy and surgical technique to patient-specific pre-procedural planning and intra-operative guidance, as well as diagnostic and therapeutic approaches in rehabilitation, pain management, and psychology. The FDA is beginning to approve these approaches for clinical use. In this review article, we summarize the application of VR and AR in clinical medicine. The history, current utility and future applications of these technologies are described. Keywords: Virtual reality; Augmented reality; Surgery; Medicine; Anatomy; Therapy INTRODUCTION DEFINITIONS AND BRIEF HISTORY Recalling the 1966 science fiction film “Fantastic Voyage”, watching The human visual system in amazement as the doctors traveled inside the patient’s body to repair a brain injury. -

Virtual Reality and Virtual Reality System Components Oluleke

Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference On Systems Engineering and Modeling (ICSEM-13) Virtual Reality and Virtual Reality System Components Oluleke Bamodu1,2, a and Xuming Ye1, b 1 College of Mechanical Engineering, Shenyang University, Shenyang, China 2 Faculty of Computing, Engineering and Technology, Staffordshire University, United Kingdom [email protected], [email protected] Keywords: virtual reality, VR, virtual reality system, hardware, software, VR engine. Abstract. This paper is a synoptic review of virtual reality, its features, types, and virtual reality systems, as well as the elements of the VR system hardware and software, which are essential components of virtual reality systems. Introduction Applications of Virtual Reality (VR) have and continue to increase over the last couple of years. This is partly due to its usefulness in many fields and as a result of the attention given to it by the media. This trend is expected to continue in the future with the advancement of technology in areas like computer graphics, computer vision, controls, image processing and other technology-affiliated components. This paper aims to dissect the nature, the role, the component, the application and applicability of the virtual reality system, as well as, explore briefly the characteristics and use of VR system hardware and software. Definition of Virtual Reality Defining Virtual Reality can prove to be a difficult task because there is no standard definition for it. It is said to be an oxymoron, as it is referred to by some school of thought as “reality that does not exist” [1]. Many different fields have different meaning associated to it, while some people have even misused the term in many cases. -

Adam NOWAK Czcionka Times New Roman (TNR) 13

SILESIAN UNIVERSITY OF TECHNOLOGY PUBLISHING HOUSE SCIENTIFIC PAPERS OF THE SILESIAN UNIVERSITY OF TECHNOLOGY 2019 ORGANISATION AND MANAGEMENT SERIES NO. 134 1 POPULAR STRATEGIES AND METHODS FOR USING AUGMENTED 2 REALITY 3 Dawid PIECHACZEK1*, Ireneusz JÓŹWIAK2 4 1 University of Science and Technology, Wroclaw; [email protected], 5 ORCID: 0000-0001-6670-7568 6 2 University of Science and Technology, Wroclaw; [email protected], 7 ORCID: 0000-0002-2160-7077 8 * Correspondence author 9 Abstract: Augmented reality (AR) is a modern technology which integrates 3D virtual objects 10 into the real environment in real time. It can be used for many purposes, which should improve 11 different processes in daily life. The paper will analyze the areas in which this technology is 12 currently used. First, the history of the development of augmented reality will be recalled. 13 Then, this technology will be compared to virtual reality because these terms are often 14 incorrectly used interchangeably. This paper describes the tools and popular platform solutions 15 related to augmented reality. The most common problems related to the use of this technology 16 will be discussed, including popular approaches concerning optical and video combining 17 methods. The existing applications and their potential in solving everyday problems will be 18 analyzed. Finally, the perspectives for the development of augmented reality and its possibilities 19 in the future will be discussed. This paper provides a starting point for using and learning about 20 augmented reality for everyone. 21 Keywords: augmented reality, graphical elements, image processing, image recognition. 22 1. -

Augmented Reality, Virtual Reality, & Health

University of Massachusetts Medical School eScholarship@UMMS National Network of Libraries of Medicine New National Network of Libraries of Medicine New England Region (NNLM NER) Repository England Region 2017-3 Augmented Reality, Virtual Reality, & Health Allison K. Herrera University of Massachusetts Medical School Et al. Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Follow this and additional works at: https://escholarship.umassmed.edu/ner Part of the Health Information Technology Commons, Library and Information Science Commons, and the Public Health Commons Repository Citation Herrera AK, Mathews FZ, Gugliucci MR, Bustillos C. (2017). Augmented Reality, Virtual Reality, & Health. National Network of Libraries of Medicine New England Region (NNLM NER) Repository. https://doi.org/ 10.13028/1pwx-hc92. Retrieved from https://escholarship.umassmed.edu/ner/42 Creative Commons License This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 4.0 License. This material is brought to you by eScholarship@UMMS. It has been accepted for inclusion in National Network of Libraries of Medicine New England Region (NNLM NER) Repository by an authorized administrator of eScholarship@UMMS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Augmented Reality, Virtual Reality, & Health Zeb Mathews University of Tennessee Corina Bustillos Texas Tech University Allison Herrera University of Massachusetts Medical School Marilyn Gugliucci University of New England Outline Learning Objectives Introduction & Overview Objectives: • Explore AR & VR technologies and Augmented Reality & Health their impact on health sciences, Virtual Reality & Health with examples of projects & research Technology Funding Opportunities • Know how to apply for funding for your own AR/VR health project University of New England • Learn about one VR project funded VR Project by the NNLM Augmented Reality and Virtual Reality (AR/VR) & Health What is AR and VR? F. -

Visual Tracking for Augmented Reality

Visual Tracking for Augmented Reality Georg Klein King’s College A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy January 2006 Declaration This dissertation is submitted to the University of Cambridge in partial fulfilment for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. It is an account of work undertaken at the Department of Engineering between October 2001 and January 2006 under the supervision of Dr T.W. Drummond. It is the result of my own work and includes nothing which is the outcome of work done in collaboration except where specifically indicated in the text. This disser- tation is approximately 50,000 words in length and contains 39 figures. Georg Klein Acknowledgements I thank my supervisor, Dr. Tom Drummond, and my colleagues in the Fall- side lab for their help and friendship. I have learned a great deal from them and hope they have enjoyed the last four years as much as I have. I am grateful to the Gates Cambridge Trust for funding my research, and to Joe Newman for donating the Sony Glasstron display which made my work on Augmented Reality possible. Finally I would like to thank my parents for their patience and continual support. Abstract In Augmented Reality applications, the real environment is annotated or enhanced with computer-generated graphics. These graphics must be ex- actly registered to real objects in the scene and this requires AR systems to track a user’s viewpoint. This thesis shows that visual tracking with in- expensive cameras (such as those now often built into mobile computing devices) can be sufficiently robust and accurate for AR applications. -

Cinematic Virtual Reality: Evaluating the Effect of Display Type on the Viewing Experience for Panoramic Video

Cinematic Virtual Reality: Evaluating the Effect of Display Type on the Viewing Experience for Panoramic Video Andrew MacQuarrie, Anthony Steed Department of Computer Science, University College London, United Kingdom [email protected], [email protected] Figure 1: A 360° video being watched on a head-mounted display (left), a TV (right), and our SurroundVideo+ system (centre) ABSTRACT 1 INTRODUCTION The proliferation of head-mounted displays (HMD) in the market Cinematic virtual reality (CVR) is a broad term that could be con- means that cinematic virtual reality (CVR) is an increasingly popu- sidered to encompass a growing range of concepts, from passive lar format. We explore several metrics that may indicate advantages 360° videos, to interactive narrative videos that allow the viewer to and disadvantages of CVR compared to traditional viewing formats affect the story. Work in lightfield playback [25] and free-viewpoint such as TV. We explored the consumption of panoramic videos in video [8] means that soon viewers will be able to move around in- three different display systems: a HMD, a SurroundVideo+ (SV+), side captured or pre-rendered media with six degrees of freedom. and a standard 16:9 TV. The SV+ display features a TV with pro- Real-time rendered, story-led experiences also straddle the bound- jected peripheral content. A between-groups experiment of 63 par- ary between film and virtual reality. ticipants was conducted, in which participants watched panoramic By far the majority of CVR experiences are currently passive videos in one of these three display conditions. Aspects examined 360° videos. -

The Effect of User Embodiment in AV Cinematic Experience

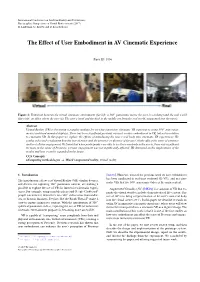

International Conference on Artificial Reality and Telexistence Eurographics Symposium on Virtual Environments (2017) R. Lindeman, G. Bruder, and D. Iwai (Editors) The Effect of User Embodiment in AV Cinematic Experience Joshua Chen1, Gun Lee2;1y, Mark Billinghurst2;1, Robert W. Lindeman1, Christoph Bartneck1 1The Human Interface Technology Laboratory New Zealand, University of Canterbury, New Zealand 2School of Information Technology & Mathematical Sciences, University of South Australia, Australia Figure 1: Transition between the virtual cinematic environment (far left: a 360◦ panoramic movie the user is watching) and the real world (far right: an office where the user is). The user’s hand and the desk in the middle are from the real world, augmented into the movie. Abstract Virtual Reality (VR) is becoming a popular medium for viewing immersive cinematic experiences using 360◦ panoramic movies and head mounted displays. There are previous research on user embodiment in real-time rendered VR, but not in relation to cinematic VR based on 360 panoramic video. In this paper we explore the effects of introducing the user’s real body into cinematic VR experiences. We conducted a study evaluating how the type of movie and user embodiment affects the sense of presence and user engagement. We found that when participants were able to see their own body in the VR movie, there was significant increase in the sense of Presence, yet user engagement was not significantly affected. We discuss on the implications of the results and how it can be expanded in the future. CCS Concepts •Computing methodologies ! Mixed / augmented reality; Virtual reality; 1. Introduction VR is capable of “transporting” users completely from their real physical environments into virtual environments (VEs), creating a The introduction of low cost Virtual Reality (VR) display devices, strong perception of Presence. -

A Study of Body Gestures Based Input Interaction for Locomotion in HMD-VR Interfaces in a Sitting Position

Report: State of the Art Seminar A Study of Body Gestures Based Input Interaction for Locomotion in HMD-VR Interfaces in a Sitting Position By Priya Vinod (Roll No: 176105001) Guided By Dr. Keyur Sorathia Department of Design Indian Institute of Technology, Guwahati, Assam, India 1 Table of Contents 1. Abstract 4 2. Introduction to VR 5 3. Navigation in VR 5 3.1. Definition of Navigation 5 3.2. Importance of Navigation in VR 6 3.3. Taxonomy of virtual travel techniques 8 3.4. Quality Factors of effective travel techniques 8 4. The Literature on Categories of Travel Techniques 8 4.1. Artificial Locomotion Techniques 9 4.2. Natural Walking Techniques 9 4.2.1. Repositioning Systems 9 4.2.2. Redirected Walking 10 4.2.3. Proxy Gestures 11 5. Literature review on Proxy Gestures for Travel in VR 13 5.1. Standing Based Natural Method of Travel in VR 13 5.1.1. Issues in Standing Position for travel in VR 15 5.2. Sitting Based Natural Method of Travel in VR 16 5.2.1. Research Gap in sitting based natural method of travel 21 6. Research Questions 22 7. Methodology 22 8. References 23 2 Figures Figure 1 Taxonomy of Virtual Travel Techniques. Figure 2 Nilsson, Serafin, and Nordahl’s (2016b) taxonomy of virtual travel techniques. Figure 3 Artificial Locomotion Techniques. Figure 4 Three categories of natural walking techniques. Figure 5 Four examples of repositioning systems: (a) a traditional linear treadmill, (b) motorized floor tiles, (c) a human-sized hamster ball, and (d) a friction-free platform. -

The Right to an Artificial Reality? Freedom of Thought and the Fiction of Philip K

Michigan Technology Law Review Article 6 2021 The Right to an Artificial Reality? rF eedom of Thought and the Fiction of Philip K. Dick Marc Jonathan Blitz Oklahoma City University Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.law.umich.edu/mtlr Part of the Entertainment, Arts, and Sports Law Commons, First Amendment Commons, Law and Society Commons, and the Science and Technology Law Commons Recommended Citation Marc J. Blitz, The Right to an Artificial Reality? rF eedom of Thought and the Fiction of Philip K. Dick, 27 MICH. TECH. L. REV. 377 (2021). Available at: https://repository.law.umich.edu/mtlr/vol27/iss2/6 This Special Essay is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Michigan Technology Law Review by an authorized editor of University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE RIGHT TO AN ARTIFICIAL REALITY? FREEDOM OF THOUGHT AND THE FICTION OF PHILIP K. DICK Marc Jonathan Blitz* Table of Contents INTRODUCTION...................................................................................... 377 I. Self-Deception and the Argument Against First Amendment Coverage of Artificial Reality....................... 380 II. The First Amendment Value of Artificial Reality ........... 383 III. Artificial Reality as an Enhancement of Brain-Generated Reality ....................................................... 387 IV. The Harms to Oneself and -

The Effect of User Embodiment in AV Cinematic Experience

International Conference on Artificial Reality and Telexistence Eurographics Symposium on Virtual Environments (2017) R. Lindeman, G. Bruder, and D. Iwai (Editors) The Effect of User Embodiment in AV Cinematic Experience Paper ID: 1036 Figure 1: Transition between the virtual cinematic environment (far left: a 360◦ panoramic movie the user is watching) and the real world (far right: an office where the user is). The user’s hand and the desk in the middle are from the real world, augmented into the movie. Abstract Virtual Reality (VR) is becoming a popular medium for viewing immersive cinematic VR experiences using 360◦ panoramic movies and head mounted displays. There has been significant previous research on user embodiment in VR, but not in relation to cinematic VR. In this paper we explore the effects of introducing the user’s real body into cinematic VR experiences. We conducted a study evaluating how the type of movie and the presence or absence of the user’s body affects the sense of presence and level of user engagement. We found that when participants were able to see their own body in the movie, there was significant increase in the sense of Presence, yet user engagement was not significantly affected. We discussed on the implications of the results and how it can be expanded in the future. CCS Concepts •Computing methodologies ! Mixed / augmented reality; Virtual reality; 1. Introduction [Sch10]. However, most of the previous work on user embodiment has been conducted in real-time rendered 3D VEs, and not cine- The introduction of low cost Virtual Reality (VR) display devices, matic VEs that use 360◦ panoramic video as the main content.