Blood Transfusion Officer” and British Planning for the Outbreak of the Second Worldwar

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Obituary LIONEL ERNEST HOWARD WHITBY, Kt., C.V,Q., M.C., M.A., M.D., F.R.C.P., Hon.D.Sc.(Toronto), Hon.LL.D.(Glasg.), -Hon.M.D.(Louvain), D.P.H

J R Army Med Corps: first published as 10.1136/jramc-103-02-09 on 1 April 1957. Downloaded from 102 Obituary LIONEL ERNEST HOWARD WHITBY, Kt., C.V,Q., M.C., M.A., M.D., F.R.C.P., Hon.D.Sc.(Toronto), Hon.LL.D.(Glasg.), -Hon.M.D.(Louvain), D.P.H. THE facilities provided today by the National Blood Transfusion Service make it difficult to appreciate the trouble a transfusion entailed less than twenty-five years ago. Probably the greatest single factor responsible for the change was the Army Transfusion Service, developed during the last war. The inspiration and organizing genius behind this pioneer service, which has teen taken as a pattern by so many others since, was Brigadier Sir Lionel Whitby, whose death occurred on November 24th, 1956, after an operation, at the age of 61. By his death the Army has lost one of its most eminent Honorary Consultants and a staunch friend. Lionel Ernest Howard Whitby was born on May 8th, 1895, and was educated at Bromsgrove School and Downing College, Cambridge. He had won an open scholarship but before taking it up, joined the Royal Fusiliers on the outbreak . of the First World War. The following year he was commissioned in the Royal guest. Protected by copyright. West Kent Regiment and in 1917 was awarded the M.C. for gallantry at Pas schendaele. In 1918, when a machine-gun officer with the rank of Major, he was severely wounded and had a leg amputated near the hip. After his recovery he studied medicine at Cambridge and at the Middlesex Hospital where he was a scholar and a prizeman, qualifying in 1923. -

By Stan/Ey French the History of DOWNING COLLEGE CAMBRIDGE

The History of DOWNING COLLEGE CAMBRIDGE by Stan/ey French The History of DOWNING COLLEGE CAMBRIDGE by Stan/ey Fre11ch DOWNING COLLEGE ASSOCIATION 1978 CONTENTS CHAPTER I THE MARRIAGE 7 CHAPTER 2 UNBREAKABLE BOND 15 CHAPTER 3 THE OLD MAID 23 CHAPTER4 THE GRASS WIDOWER 31 CHAPTER 5 THE LAST OF THE LINE 43 CHAPTER 6 INTO CHANCERY 51 CHAPTER 7 WICKED LADY 59 CHAPTER 8 INDEFATIGABLE CHAMPION 67 CHAPTER 9 UPHILL ALL THE WAY 77 CHAPTER 10 THE IDEAL AND THE REAL 82 CHAPTER 11 FRANCIS ANNESLEY AND HIS COLLEAGUES 89 CHAPTER 12 OPENED FOR EDUCATION 95 CHAPTER 13 TROUBLE IN ARCADY Ill CHAPTER 14 STAGNATION AND PROGRESS 124 CHAPTER 15 ACHIEVEMENT 132 THE FOUNDER'S FAMILY TREE 142 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS 143 PRINCIPAL SOURCES 144 ILLUSTRATIONS 1. Cover: Sir George Downing, third baronet, founder of Downing College, Cambridge. (From a miniature owned by Capt. G. D. Bowles.) 2. Frontspiece: Francis Annesley, Master 1800-1812 without whose persistence Downing College would not have been founded. (From the copy in the Senior Combination Room, Downing College of the portrait by A. Hickel at Reading Town Hall.) 3. Sir George Downing, first baronet, founder of the Downing fortune. (From a copy of the portrait at Harvard.) 13 .,. 4. Lady {Mary) Downing, n~e Forester, wife of the third baronet. (From the portrait at Willey Hall; photograph given by the late Lord Forester.) 25 5. Lady (Margaret) Downing, nle Price, wife of the fourth baronet. {From the portait in Downing College Hall.) 63 6. Downing College as it might have been. (From an engraving at Downing College, of an illustration in Le Keux, Cambridge, 1862.) 85 7. -

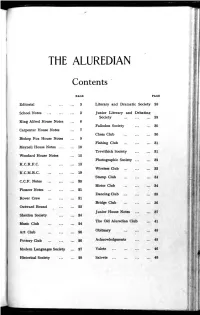

The Aluredian

THE ALUREDIAN Contents · PAGE PAGE Editorial 3 Literary and Dramatic Society 28 School Notes 3 junior Literary and Debatin~ Society 29 King Alfred House Notes 6 Fallodon Society 30 Carpenter House Notes 7 Chess Club 30 Bishop Fox House Notes 9 Fishing Club 31 Meynell House Notes ... 10 Trevithick Society 31 Woodard House Notes 12 Photographic Society 32 K.C.R.F.C. 13 Wireless Club 83 K.C.M.R.C. 19 Stamp Club 34 C.C.F . Notes 20 Motor Club 34 Pioneer Notes 21 Dancing Club 35 Rover Crew 21 Bridge Club 36 Outward Bound 22 Junior House Notes 37 Sheldon Society 24 The Old Aluredian Club u Music Club 24 Obituary Art Club 26 45 Pottery Club 26 Acknowledgments 45 Modem Languages Society 27 Valete 46 Historical Society 28 Salvete 48 THE ALUREDIAN EDITOR : J. H. CATLIN. SuB-EDITORs: A. J. HOLLAND, R. J. A. ABRAHAM. VoL. XXVIII. No . 6. FEBRUARY, 1957. Editorial HE Editorial of a magazine has in past centuries often been the place T where the Editor took the chance of explaining to readers what an excellent Magazine they were about to read. Here we do not wish to do only this, but to thank all our contributors for their work, without which the Magazine would obviously not appear. We would also like to re mind any would-be writers of original compositions, either verse or prose, that although it is not usual to publish original works in the Michaelmas Term, it is never too soon to start thinking of a contribution to the Lent and Summer issue. -

Our Blood Your Money

Our Blood Your Money The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Hedley-Whyte, John, and Debra R. Milamed. 2013. “Our Blood Your Money.” The Ulster Medical Journal 82 (2): 114-120. Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:11877112 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA Ulster Med J 2013;82(2):114-120 Medical History Our Blood Your Money John Hedley-Whyte, Debra R. Milamed Accepted 26 July 2012 SUMMARY Dublin-born and Yale-trained Joseph Eastman Sheehan, Lord Nuffield’s choice for Professor of Plastic and Reconstructive On June 3, 1939, Donegal-born James C. Magee was Surgery5. Elósegui’s Nationalist Blood Transfusion Service appointed U.S. Army Surgeon General by President Franklin transfused an estimated 25,000 times before Franco’s victory6. Delano Roosevelt. On May 31, 1940, Magee appointed Professor Walter B. Cannon of Harvard University as Chairman of the U.S. National Research Council Committee on Shock and Transfusion. In 1938 Brigadier Lionel Whitby was appointed Director of an autonomous U.K. Army Blood Transfusion Service (ABTS). Whitby thereupon appointed Professor John Henry Biggart, Professor of Pathology, Queen’s University, his Northern Ireland Head of Blood Transfusion and Blood Banking. Winston S. Churchill was aware that Biggart’s service would be responsible for the needs of the Allied Forces and later for the United States Forces in Northern Ireland. -

Lobar Pneumonia Treated by Musgrave Park Physicians

Lobar Pneumonia Treated by Musgrave Park Physicians The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Hedley-Whyte, John, and Debra R. Milamed. 2009. Lobar pneumonia treated by Musgrave Park physicians. The Ulster Medical Journal 78(2): 119-128. Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:4732014 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA Ulster Med J 2009;78(2):119-128 Medical History Lobar pneumonia treated by Musgrave Park physicians John Hedley-Whyte, Debra R Milamed Accepted 5 January 2009 SUMMARY this Unit devoted to the study of Allied War Wounds and their infection. Harvard’s US 5th General Hospital was also In the decade 1935-45 the treatment of lobar pneumonia stationed in Boulogne with Professor Harvey Cushing as in the developed and warring world underwent a series of Commanding Officer, and Professor Roger Lee as Chief of evolutions—anti-sera, specific anti-sera, refinement of sulpha Medicine. Both were friends of Wright’s group, and Cushing drugs, sulpha and anti-sera, the introduction of penicillin for collaborated in Wright’s work on war wounds9,10. In 1919 bacteriology, then ophthalmology, and then for penicillin- Harvey Cushing was awarded an honorary MD by Queen’s, sensitive bacterial infections such as lobar pneumonia with its Belfast10. Cushing was in 1926-27 to train Hugh Cairns11, many Cooper types of Streptococcus pneumoniae. -

Trinity College Cambridge

TRINITY COLLEGE cambridge annual record 2011 Trinity College Cambridge Annual Record 2010–2011 Trinity College Cambridge CB2 1TQ Telephone: 01223 338400 e-mail: [email protected] website: www.trin.cam.ac.uk Cover photo: ‘Through the Window’ by frscspd Contents 5 Editorial 7 The Master 13 Alumni Relations and Development 14 Commemoration 21 Trinity A Portrait Reviewed 24 Alumni Relations and Associations 33 Annual Gatherings 34 Alumni Achievements 39 Benefactions 57 College Activities 59 First & Third Trinity Boat Club 62 Field Club 81 Societies and Students’ Union 93 College Choir C ontent 95 Features 96 The South Side of Great Court 100 Trinity and the King James Bible S 108 Night Climbing 119 Fellows, Staff and Students 120 The Master and Fellows 134 Appointments and Distinctions 137 In Memoriam 153 An Eightieth Birthday 162 A Visiting Year at Trinity 167 College Notes 179 The Register 180 In Memoriam 184 Addresses Wanted 205 An Invitation to Donate TRINITY ANNUAL RECORD 2011 3 Editorial In its first issue of this academical year the Cambridge student newspaper Varsity welcomed Freshers—since one cannot apparently have freshmen and certainly not freshwomen—to ‘the best university in the world’. Four different rankings had given Cambridge the top position. Times Higher Education puts us sixth (incomprehensibly, after Oxford). While all league tables are suspect, we can surely trust the consistency of Cambridge’s position in the world’s top ten. Still more trust can be put in the Tompkins table of Tripos rankings that have placed Trinity top in 2011, since Tripos marks are measurable in a way that ‘quality and satisfaction’ can never be. -

The Eagle 1988

THE EAGLE A MAGAZINE SUPPORTED BY MEMBERS OF ST JOHN'S COLLEGE, CAMBRIDGE FOR SUBSCRIBERS ONLY Vol. LXXI No. 296 EASTER 1988 Senior Editor: Or Robert To mbs Junior Editors: Miss Natasha Waiter Editorial Secretary: Mrs Jane Jones Editorial Committee: Or H.R.L. Beadle Or P.P. Sims-Williams Or I.M. Hutchings Treasurer: Mr AA Macintosh College Notes compiled by Mr Norman Buck. Wordsworth's Mathematical Education When William Wordsworth went up to St John's in October 1787 he was expected to study mathematics as his major subject. Why was this, what types of mathematics were then being taught, and what did he achieve? CONTENTS At Cambridge at that time the influence of Sir Isaac Newton, who was professor of mathematics there from 1669 to.1 702, was still of great importance. Mathematics was the dominant subject in th e university, and its study was compulsory for all students, WORDSWORTH'S MATHEMATICAL EDUCATION by Charlotte Kipling MA 3 together with moral philosophy and theology. The students had no choice of subjects. The final degree examination (the Tripos) was in mathematics, philosophy and theology, JOHNIANA 11 but honours were limited to those candidates excelling in mathematics, The undergraduates were allocated in classes before the examination, with a right of appeal THE FIRST ENGLISH VITA NUOVA, by George Watson 12 for those who considered they had been placed too low. The results of the examination determined where they were placed in order of merit within the class. Consequently THE WINTHROP FAMILY AND ST JOHN'S COLLEGE, th ere was intense competition between the candidates, particularly between those by Maurice V. -

Sir Winston Churchill

J R Coll Physicians Edinb 2017; 47: 388–94 | doi: 10.4997/JRCPE.2017.418 PAPER Sir Winston Churchill: treatment for pneumonia in 1943 and 1944 HistoryJA Vale1, JW Scadding2 & Humanities This paper reviews Churchill’s illnesses in February 1943 and August/ Correspondence to: September 1944 when he developed pneumonia; on the rst occasion this JA Vale Abstract followed a cold and sore throat. Churchill was managed at home by Sir NPIS (Birmingham Unit) Charles Wilson (later Lord Moran) with the assistance of two nurses and the City Hospital expert advice of Dr Geoffrey Marshall, Brigadier Lionel Whitby and Colonel Birmingham B18 7QH Robert Drew. A sulphonamide (sulphathiazole on the rst occasion) was UK prescribed for both illnesses. Churchill recovered, and despite his illnesses continued to direct the affairs of State from his bed. On the second occasion, Churchill’s illness was not made Email: public. [email protected] Keywords: Churchill, Drew, Marshall, Whitby, Wilson (Moran) Declaration of Interests: No confl ict of interests declared Introduction February 1943 We review Churchill’s illnesses in February 1943 and August/ Churchill returned from Algiers to Britain on Sunday 7 September 1944 and their management, and discuss February 1943, a fl ight of eight and a half hours, and later whether Churchill’s ability to direct the affairs of State was presided over his fi rst War Cabinet in four weeks. compromised during these illnesses. Following his return, Churchill maintained his customary Methods work output and gave a two hour speech1 in the House of Commons on 11 February 1943 on the war situation, Information regarding Churchill’s illnesses was available from specifi cally the Conference at Casablanca.25 However, when various sources. -

A Handbook of Who Lived Where in Hampton Court Palace 1750 to 1950 Grace & Favour a Handbook of Who Lived Where in Hampton Court Palace 1750 to 1950

Grace & Favour A handbook of who lived where in Hampton Court Palace 1750 to 1950 Grace & Favour A handbook of who lived where in Hampton Court Palace 1750 to 1950 Sarah E Parker Grace & Favour 1 Published by Historic Royal Palaces Hampton Court Palace Surrey KT8 9AU © Historic Royal Palaces, 2005 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. ISBN 1 873993 50 1 Edited by Clare Murphy Copyedited by Anne Marriott Printed by City Digital Limited Front cover image © The National Library, Vienna Historic Royal Palaces is a registered charity (no. 1068852). www.hrp.org.uk 2 Grace & Favour Contents Acknowledgements 4 Preface 5 Abbreviations 7 Location of apartments 9 Introduction 14 A list of who lived where in Hampton Court Palace, 1750–1950 16 Appendix I: Possible residents whose apartments are unidentified 159 Appendix II: Senior office-holders employed at Hampton Court 163 Further reading 168 Index 170 Grace & Favour 3 Acknowledgements During the course of my research the trail was varied but never dull. I travelled across the country meeting many different people, none of whom had ever met me before, yet who invariably fetched me from the local station, drove me many miles, welcomed me into their homes and were extremely hospitable. I have encountered many people who generously gave up their valuable time and allowed, indeed, encouraged me to ask endless grace-and-favour-related questions. -

Our Blood Your Money the Harvard Community Has Made This Article

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Harvard University - DASH Our Blood Your Money The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters. Citation Hedley-Whyte, John, and Debra R. Milamed. 2013. “Our Blood Your Money.” The Ulster Medical Journal 82 (2): 114-120. Accessed February 19, 2015 2:34:12 PM EST Citable Link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:11877112 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University's DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms- of-use#LAA (Article begins on next page) Ulster Med J 2013;82(2):114-120 Medical History Our Blood Your Money John Hedley-Whyte, Debra R. Milamed Accepted 26 July 2012 SUMMARY Dublin-born and Yale-trained Joseph Eastman Sheehan, Lord Nuffield’s choice for Professor of Plastic and Reconstructive On June 3, 1939, Donegal-born James C. Magee was Surgery5. Elósegui’s Nationalist Blood Transfusion Service appointed U.S. Army Surgeon General by President Franklin transfused an estimated 25,000 times before Franco’s victory6. Delano Roosevelt. On May 31, 1940, Magee appointed Professor Walter B. Cannon of Harvard University as Chairman of the U.S. National Research Council Committee on Shock and Transfusion. In 1938 Brigadier Lionel Whitby was appointed Director of an autonomous U.K. Army Blood Transfusion Service (ABTS). -

102 Obituary LIONEL ERNEST HOWARD WHITBY, Kt., C.V,Q., M.C., M.A., M.D., F.R.C.P., Hon.D.Sc.(Toronto), Hon.LL.D.(Glasg.), -Hon.M.D.(Louvain), D.P.H

J R Army Med Corps: first published as 10.1136/jramc-103-02-09 on 1 April 1957. Downloaded from 102 Obituary LIONEL ERNEST HOWARD WHITBY, Kt., C.V,Q., M.C., M.A., M.D., F.R.C.P., Hon.D.Sc.(Toronto), Hon.LL.D.(Glasg.), -Hon.M.D.(Louvain), D.P.H. THE facilities provided today by the National Blood Transfusion Service make it difficult to appreciate the trouble a transfusion entailed less than twenty-five years ago. Probably the greatest single factor responsible for the change was the Army Transfusion Service, developed during the last war. The inspiration and organizing genius behind this pioneer service, which has teen taken as a pattern by so many others since, was Brigadier Sir Lionel Whitby, whose death occurred on November 24th, 1956, after an operation, at the age of 61. By his death the Army has lost one of its most eminent Honorary Consultants and a staunch friend. Lionel Ernest Howard Whitby was born on May 8th, 1895, and was educated at Bromsgrove School and Downing College, Cambridge. He had won an open scholarship but before taking it up, joined the Royal Fusiliers on the outbreak . of the First World War. The following year he was commissioned in the Royal guest. Protected by copyright. West Kent Regiment and in 1917 was awarded the M.C. for gallantry at Pas schendaele. In 1918, when a machine-gun officer with the rank of Major, he was severely wounded and had a leg amputated near the hip. After his recovery he studied medicine at Cambridge and at the Middlesex Hospital where he was a scholar and a prizeman, qualifying in 1923. -

Downing and the Two World Wars

Bevan, Hicks & Thomson & Hicks Bevan, Downing and the two World Wars This book describes life in Downing College during the two World Wars and gives some account of the military exploits of members of the College. At the centre of the book are the reminiscences and experiences of men who were at Downing before, during, and just after the Second World War. These men are now in their late eighties or older and, if the authors had not collected their stories now they would fairly soon Wars World Downing and Two the have been lost. Some are poignant, some are funny, some conceal or play down great bravery and courage, but they are all worth preserving. In addition to individual memories, there are descriptions of what happened in College itself in the two wars. For instance, in the Second World War it was largely taken over by the RAF although it continued to be full of students, mostly on short courses before joining the forces, while in the First World War it almost emptied, being reduced to only 16 undergraduates in 1917, with the rest all having gone off to fight. The book is a useful addition to the records of the College’s history and should be read not only by members of Downing of all ages but also local historians and anyone interested in studying life during the two wars. Gwyn Bevan, John Hicks & Peter Thomson Letter from the famous burns surgeon Sir Archibald McIndoe recommending Ward Bowyer for a place Cover picture: The OTC parading outside the Hall in 1916 DOWNING AND THE TWO WORLD WARS Gwyn Bevan, John Hicks & Peter Thomson Published by The Downing College Association © 2010 While every effort has been made to trace the owners of copyright material produced herein, the publishers would like to apologise for any omissions and would be pleased to incorporate any missing acknowledgements in future editions.