Oral History Interview with Stanley Landsman, 1968 Jan. 19-22

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Modernism 1 Modernism

Modernism 1 Modernism Modernism, in its broadest definition, is modern thought, character, or practice. More specifically, the term describes the modernist movement, its set of cultural tendencies and array of associated cultural movements, originally arising from wide-scale and far-reaching changes to Western society in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Modernism was a revolt against the conservative values of realism.[2] [3] [4] Arguably the most paradigmatic motive of modernism is the rejection of tradition and its reprise, incorporation, rewriting, recapitulation, revision and parody in new forms.[5] [6] [7] Modernism rejected the lingering certainty of Enlightenment thinking and also rejected the existence of a compassionate, all-powerful Creator God.[8] [9] In general, the term modernism encompasses the activities and output of those who felt the "traditional" forms of art, architecture, literature, religious faith, social organization and daily life were becoming outdated in the new economic, social, and political conditions of an Hans Hofmann, "The Gate", 1959–1960, emerging fully industrialized world. The poet Ezra Pound's 1934 collection: Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum. injunction to "Make it new!" was paradigmatic of the movement's Hofmann was renowned not only as an artist but approach towards the obsolete. Another paradigmatic exhortation was also as a teacher of art, and a modernist theorist articulated by philosopher and composer Theodor Adorno, who, in the both in his native Germany and later in the U.S. During the 1930s in New York and California he 1940s, challenged conventional surface coherence and appearance of introduced modernism and modernist theories to [10] harmony typical of the rationality of Enlightenment thinking. -

Press Release (Pdf)

S TEPHEN H ALLER G ALLERY NEXUS July 1– August 7, 2010 Stephen Haller Gallery is pleased to announce the opening of a new exhibition: NEXUS a gathering together of key works by gallery artists and a forecast of the upcoming season. This group exhibition reveals the connections, the shared sensibility of the gallery’s core group of international artists. LINDA STOJAK’S paintings may be thought of as “psychological self-portraits.” Her iconography is the human body. Her work emerges out of a great tradition of painting and yet stands as uniquely her own. Linda Stojak’s paintings are an exploration of the very essence of what it is to be human. Her work is a highly charged yet subtle exploration of the personal, characterized by immediacy and a palpable painterly quality, and marked by a disquieting beauty. Exciting new photographer KATE O'DONOVAN COOK’S The Waldorf Series explores issues of gender and the ambiguity of relationships. O'Donovan Cook plays with the idealization of a romantic relationship, subverting it by portraying both characters: she is the male and the female engaged in this ambiguous scenario. Her work is characterized by explorations of identity through role playing in ways both theatrical and fantastical. The Waldorf Series is in the permanent collection of the Herbert F Johnson Museum at Cornell. American painter RON EHRLICH is known for achieving rich surfaces and subtleties of tone. Ehrlich melds the textures rooted in Japanese ceramics with the spontaneity and vitality of action painting. Years spent in Japan studying the art of ceramics at a monastery profoundly influenced Ehrlich’s approach to painting. -

2021 -2022 Catalog

(203) 332-5000 900 Lafayette Boulevard Bridgeport, CT 06604 WWW.HOUSATONIC.EDU 2021-2022 COLLEGE CATALOG Becoming CONNECTICUT STATE COMMUNITY COLLEGE A merger of Connecticut's 12 community colleges is underway. Connecticut State Community College (CT State), a statewide college comprised of all Connecticut's current community college locations, plans to open its doors in the Fall 2023. Here are some important facts students need to know: • the final commencement ceremony for Housatonic Community College is scheduled for May 2023. Ceremonies will continue to be held at each location as campuses of CT State. • as a part of the planned merger, students continuing their studies beyond summer term 2023 will be matched with the CT State program that most closely aligns with their Spring 2023 major and is offered at the Housatonic location, • students beginning Associate degree programs in Fall 2021 should plan with their advisor/program coordinator to attend full-time if they wish to graduate prior to the planned merger, • students who begin an Associate degree program in January 2022 would be anticipated to complete their degree at the merged college, Connecticut State Community College, • in all cases, the College is committed to students completing their education with a minimum of disruption and staying in touch with your advisor/program coordinator is essential, • further details can be found and will be updated on the Frequently Asked Questions page: http://www.ct.edu/ctstate/academics. Published August 9, 2021 All information in this catalog can be viewed online at Housatonic Community College 2021-2022 Catalog Housatonic Community College 2021-2022 Catalog 1 2 Housatonic Community College 2021-2022 Catalog Table of Contents The College reserves the right to change course offerings or to modify or change information and regulations published in this catalog. -

Dan Flavin Was Born in 1933 in New York City, Where He Later Studied Art History at the New School for Social Research and Columbia University

DAN FLAVIN Dan Flavin was born in 1933 in New York City, where he later studied art history at the New School for Social Research and Columbia University. His first solo show was at the Judson Gallery, New York, in 1961. Flavin made his first work with electric light that same year, and he began using commercial fluorescent tubes in 1963. Fluorescent light was commercially available and its defined systems of standard sized tubes and colors defied the very tenets of Abstract Expressionism and Pop Art, from which the artist sought to break free. In opposition to the gestural and hand-crafted, these impersonal prefabricated industrial objects offered, what Donald Judd described as “…a means new to art.”1 Seizing the anonymity of the fluorescent tube, Flavin employed it as a simple and direct means to implement a whole new artistic language of his own. He worked within this self-imposed reductivist framework for the rest of his career, endlessly experimenting with serial and systematic compositions to wed formal relationships of luminous light, color, and sculptural space. Vito Schnabel Gallery presented Dan Flavin, to Lucie Rie and Hans Coper, master potters in St. Moritz from December 19, 2017 — February 4, 2018. The exhibition featured nine light pieces from the series dedicated to Rie, nine works from his series dedicated to Coper, and a selection of ceramics by Rie and Coper from Flavin’s personal collection. Major solo exhibitions of Flavin’s work have been presented at the National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa; Staatliche Kunsthalle, Baden- Baden; St. Louis Art Museum, Missouri; Morgan Library and Museum, New York; and Dan Flavin: A Retrospective, an international touring exhibition that included the National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.; Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth, Texas; Museum of Contemporary Art, Chicago; Hayward Gallery, London; the Musée d’Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris; Los Angeles County Museum of Art; and Pinakothek der Moderne, Munich. -

Press Release for Immediate Release Berry Campbell Gallery Hosts Exhibition at Historic Ashawagh Hall

PRESS RELEASE FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE BERRY CAMPBELL GALLERY HOSTS EXHIBITION AT HISTORIC ASHAWAGH HALL NEW YORK, NEW YORK, SEPTEMBER 29, 2020 – Berry Campbell Gallery is pleased to present “Continuum,” a special exhibition at the historic Ashawagh Hall in Springs, East Hampton, New York. “Continuum” is a group exhibition featuring works by local contemporary artists represented by Berry Campbell: Eric Dever, Mike Solomon, Susan Vecsey, and Frank Wimberley. Ashawagh Hall is located at 780 Springs Fireplace Road in Springs, East Hampton, just a few steps from Jackson Pollock and Lee Krasner’s former home (now the Pollock-Krasner House and Study Center). Springs is known as a long-standing artist community, considered an artistic center for Abstract Expressionist artists like Jackson Pollock, Lee Krasner, James Brooks, Charlotte Park, Perle Fine, Willem de Kooning, Elaine de Kooning, and Ibram Lassaw. Berry Campbell represents many artists connected to the Hamptons community including Perle Fine, Charlotte Park, Raymond Hendler, John Opper, Syd Solomon, Larry Zox, and Dan Christensen. Started in the 1960s by the Abstract Expressionists, the “Springs Invitational” exhibition, hosted by Ashawagh Hall, is hailed as a cornerstone event of the local community. To further this tradition, Berry Campbell is featuring four of the gallery’s contemporary artists who continue this legacy by exhibiting at this historic venue. “Continuum” will be on view from Friday, October 9, 2020 through Monday, October 12, 2020 for Columbus Day weekend. Ashawagh Hall will be open with special hours: Friday, 11 am- 6 pm; Saturday, 9 am – 6 pm (Springs Farmer’s Market until 1pm); Sunday, 11 am – 6 pm; Monday (Columbus Day), 11 am – 6 pm. -

NGA | 2014 Annual Report

NATIO NAL G ALLERY OF ART 2014 ANNUAL REPORT ART & EDUCATION Juliet C. Folger BOARD OF TRUSTEES COMMITTEE Marina Kellen French (as of 30 September 2014) Frederick W. Beinecke Morton Funger Chairman Lenore Greenberg Earl A. Powell III Rose Ellen Greene Mitchell P. Rales Frederic C. Hamilton Sharon P. Rockefeller Richard C. Hedreen Victoria P. Sant Teresa Heinz Andrew M. Saul Helen Henderson Benjamin R. Jacobs FINANCE COMMITTEE Betsy K. Karel Mitchell P. Rales Linda H. Kaufman Chairman Mark J. Kington Jacob J. Lew Secretary of the Treasury Jo Carole Lauder David W. Laughlin Frederick W. Beinecke Sharon P. Rockefeller Frederick W. Beinecke Sharon P. Rockefeller LaSalle D. Leffall Jr. Chairman President Victoria P. Sant Edward J. Mathias Andrew M. Saul Robert B. Menschel Diane A. Nixon AUDIT COMMITTEE John G. Pappajohn Frederick W. Beinecke Sally E. Pingree Chairman Tony Podesta Mitchell P. Rales William A. Prezant Sharon P. Rockefeller Diana C. Prince Victoria P. Sant Robert M. Rosenthal Andrew M. Saul Roger W. Sant Mitchell P. Rales Victoria P. Sant B. Francis Saul II TRUSTEES EMERITI Thomas A. Saunders III Julian Ganz, Jr. Leonard L. Silverstein Alexander M. Laughlin Albert H. Small David O. Maxwell Benjamin F. Stapleton John Wilmerding Luther M. Stovall Alexa Davidson Suskin EXECUTIVE OFFICERS Christopher V. Walker Frederick W. Beinecke Diana Walker President William L Walton Earl A. Powell III John R. West Director Andrew M. Saul John G. Roberts Jr. Dian Woodner Chief Justice of the Franklin Kelly United States Deputy Director and Chief Curator HONORARY TRUSTEES’ William W. McClure COUNCIL Treasurer (as of 30 September 2014) Darrell R. -

Press Release for Immediate Release Berry Campbell Gallery Presents an Exhibition of Represented Artists

PRESS RELEASE FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE BERRY CAMPBELL GALLERY PRESENTS AN EXHIBITION OF REPRESENTED ARTISTS NEW YORK, NEW YORK, June 20, 2019– Berry Campbell Gallery is pleased to announce its annual exhibition, Summer Selections, a presentation of work from each of the gallery’s represented twenty-eight artists and estates. Also, included in the show will be additional works from the gallery’s inventory by Sam Gilliam, Nancy Graves, Peter Halley, Paul Jenkins, Philip Pavia, and Larry Poons. This exhibition offers a chance to view a wide variety of paintings and works on paper by important mid-century and contemporary artists. Summer Selections will open August 6 and will continue through August 16, 2019. EDWARD AVEDESIAN was born in Lowell, Massachusetts in 1936 and attended the School of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. After moving to New York City in the early 1960s, he joined the dynamic art scene in Greenwich Village, frequenting the Cedar Tavern on Tenth Street, associating with the critic Clement Greenberg, and joining a new generation of abstract artists, such as Darby Bannard, Kenneth Noland, Jules Olitski, and Larry Poons. Avedisian was among the leading figures to emerge in the New York art world during the 1960s. An artist who mixed the hot colors of Pop Art with the cool, more analytical qualities of Color Field painting, he was instrumental in the exploration of new abstract methods to examine the primacy of optical experience. WALTER DARBY BANNARD, a leader in the development of Color Field Painting in the late 1950s, was committed to color-based and expressionist abstraction for over five decades. -

Four-Seasons-Installed-Catalog.Pdf

The Four Seasons Baltimore Showcases City’s Largest Hotel Art Collection The Four Seasons Baltimore has opened with the city’s largest hotel art collection. The collection, assembled by Mark Myers of Atlantic Arts, includes museum-quality pieces informed by the Washington Color School. “The credit really has to go to the owners, Michael Beatty and his team at Harbor East Development, for having the vision to provide a first quality collection in a commercial setting. They were very specific with what they wanted to achieve with this collection,” according to Myers. Acknowledging the influencers and the influenced, the collection was assembled considering antecedents and derivatives of the Color School movement. In a gallery ambience, visitors can view the art, which includes works from well-known artists such as Gene Davis, Sam Francis, Paul Jenkins, Richard Anuszkiewicz, Sam Gilliam, Larry Poons, Ronald Davis, Larry Zox, and Frank Stella. The collection also includes pieces from renowned contemporary artists, including Susie Lee, Craig Kaft, Lisa Nankivil, and Baltimore-based Karl Connolly . Stand-out pieces in the collection are original works by Sam Gilliam (American, b. 1933) and Ronald Davis (American, b. 1937). “Suite 16” Richard Anuszkiewicz (American, b. 1930) The large Anuszkiewicz works in the lobby are the set of four dramatic optical art prints from 1977 titled “Suite 16”. Anuszkiewicz, one of the founders of Optical Art, a late 1960s and early 1970s art movement, was hailed by Life magazine in 1964 as "one of the new wizards of Op," and his work was later described by the New York Times: “The drama -- and that feels like the right word -- is in the subtle chemistry of complementary colors, which makes the geometry glow as if light were leaking out from behind it.” “Quarterdeck” “Moby Dick” “Ahab’s Leg” “The Hyena” Frank Stella (American, b. -

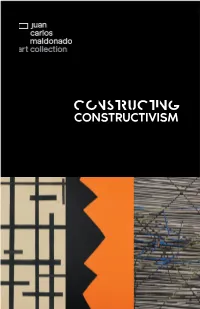

Constructing Constructivism Exhibited Artists

CONSTRUCTING CONSTRUCTIVISM EXHIBITED ARTISTS ABEND Harry BARSOTTI Hercules BOLOTOWSKY Ilya CAIROLI Carlos CALDER Alexander CLARK Lygia CRUZ-DIEZ Carlos DAVIS Gene DE CASTRO Willys DEBOURG Narciso DILLER Burgoyne FERRARI Leon GEGO GRAHAM Dan KUWAYAMA Tadaaki LLORENS Antonio NARVAEZ Francisco NEDO NEGRET Edgar NOLAND Kenneth PAPE Lygia PARDO Mercedes PUENTE Alejandro RAMIREZ VILLAMIZAR Eduardo ROITMAN Volf ROJAS Carlos SALAZAR Francisco SCHÖFFER Nicolas SMITH Leon Polk SOTO Jesus Rafael STEIN Joël GEGO, Dibujo sin Papel (detail), 1985 WILLIAMS Neil Cover: Burgoyne Diller, Untitled, 1940 (detail); Leon Polk Smith, Correspondence Black Yellow, ZOX Larry 1963 (detail); Jesús Soto, Vibrations, 1960 (detail) CONSTRUCTING CONSTRUCTIVISM GEGO, Dibujo sin Papel (detail), 1985 Alexander Calder, Fourteen Black Leaves, 1961. 11 3/4 x 41 3/4 x 20 1/2 in 5 Since its beginnings in 2005, the driving force behind the Juan Carlos Maldonado Art Collection, JCMAC, has been a recognition of the contribution that Geometric Abstraction has made to art history in the twentieth century. In 2016 the JCMAC began a new chapter, opening its acclaimed exhibition space in Miami’s Design District to bring about meaningful dialogues around the artists in the collection at an international level. Our collection has historically focused on Latin American Geometric Abstraction (1940 - 1970), a well-known sub-sector of the broader Geometric Abstraction style prevalent during the postwar period. With avidity, the collection has recently expanded to include artists from Europe and North America. This new intention has allowed us to better contextualize the work of Latin American artists and provide a deeper analysis of the importance of Geometric Abstraction in a globalized world. -

Introduction Recently Acquired: New Art in The

Recently Acquired: New Art in the Collection February 2 – March 1, 2008 University of Wyoming Art Museum 2008 Educational Packet developed for grades K-12 The Art Museum has acquired a number of new and important works over the last year, adding such important artists to the collection as Helsinski artist, Kaarina Kaikkonen. Recently Acquired: New Art in the Collection presents a selection of these new acquisitions, including selected works from a JP Morgan/Chase Manhattan Art Program gift to the Art Museum. Purpose and Focus of this packet: This packet provides K-12 teachers with background information on the exhibits and suggested age appropriate applications for exploring the concepts, meaning and artistic intent of the work exhibited, before, during and after the museum visit. The focus of this educational packet and curricular unit is for students to observe the work of ten diverse artists working in varied media, to question the work, to explore it, to create their own work, and to reflect back on the entire process. Curricular Unit Topic: From Concept to Creation: Communicating through Medium Introduction Question: “I have heard enough of politicians talking about Students will have an opportunity to read, write, ‘change.’ We’ve seen it being used ad nauseam,” [Robert] sketch, listen to museum educators and artists, and, Redford told Thursday’s opening night audience for the then, come up with questions about the subjects and 2008 festival at Eccles Theatre in Park City, Utah. objects in the work, and the concepts behind the art work. They will, also, come up with questions on the If you want real change, according to Redford, find artist’s use of media and each artist’s style. -

Greenwich Village Society for Historic Preservation Oral History Project

GREENWICH VILLAGE SOCIETY FOR HISTORIC PRESERVATION ORAL HISTORY PROJECT Oral History Interview PAULA DELUCCIA POONS By Sarah Dziedzic Brooklyn, NY September 27, 2017 Oral History Interview with Paula DeLuccia Poons, September 27, 2017 Narrator(s) Paula DeLuccia Poons Birthyear 1953 Birthplace Paterson, NJ Narrator Age 64 Interviewer Sarah Dziedzic Poons’s apartment in 827–831 Place of Interview Broadway Date of Interview September 27, 2017 Duration of Interview 95 mins Number of Sessions 1 Waiver Signed/copy given Y Photographs Y Archival Format .wav 44kHz/16bit Poons_PaulaGVSHPOralHistory_Archi Archival File Names val.wav [1.01 GB] Poons_PaulaGVSHPOralHistory_Acces MP3 File Name s.mp3 [114 MB] Portions Omitted from Recordings n/a Order in Oral Histories 34 [#4 2017] Poons–ii Paula DeLuccia Poons, Photo by Sarah Dziedzic Poons–iii Quotes from Oral History Interview with Paula DeLuccia Poons Sound-bite “Paula DeLuccia, also known at Paula DeLuccia Poons. I was born in Paterson, New Jersey, in 1953. And I’m an artist”… “Larry moved in here in ’74…maybe it was ‘74 the first time I saw this space. And it had been William Rubin’s space before Larry took it over, and William Rubin had been the director of the painting department at the Museum of Modern Art. And he had Richard Meier design the space…and it was like you were walking into, basically like a museum. I mean, it was quiet, it was like a different world”… “Elaine de Kooning lived on the third floor. Jules Olitski lived on the second floor; Paul Jenkins lived across the hall; and a woman named Royalene Ward lived upstairs in the penthouse”… “In the back, that’s where the studios are…Larry had been working there from ‘74 to ‘89 when he dripped paint, and it went downstairs, and the landlord had a brass needle point shower that Cyndi Lauper was going to buy, and it suddenly had pink paint on it. -

212.924.2178 | | [email protected]

530 West 24th St, New York, NY 10011 | 212.924.2178 | www.berrycampbell.com | [email protected] PRESS RELEASE FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE YVONNE THOMAS: WINDOWS AND VARIATIONS (1963-1965) OPENS THE FALL SEASON AT BERRY CAMPBELL NEW YORK, NEW YORK, JULY 17, 2019—Berry Campbell is pleased to announce an important exhibition of paintings by legendary abstract painter, Yvonne Thomas. This historic exhibition is a finely curated group of sixteen paintings from 1963 – 1965. The repetitive footprint rectangle shapes in these works are intriguing: some seem meant to be distinct shapes, gone over by the artist additively to define and clarify their contours; others are subtractive, consisting of scraped rectangles. Still others appear to consist just of direct strokes of paint applied with wide brushes. These forms derive from the more defined elements that began to emerge in Thomas’s Abstract Expressionist work in the 1950s, but here she took what had been spontaneous marks and made them conscious and deliberate. The exhibition will open the 2019 fall season with a reception on Thursday, September 5, 2019 from 6 to 8 pm and continues through October 5, 2019. In 1963, a significant change occurred in the art of Yvonne Thomas. Whereas in the 1950s, she had let her paintings lead her in the ways they evolved, following their logic, she now took control of them through a more consistent and systematic approach. The works she produced concur with the ethos of the abstract art of the time. In the view that the gesturalism of Abstract Expressionism had foreclosed the mental and preplanned methods that had been important in the art of the past, artists began to bring a conceptual ideas back into their works.