Differential Virus Host-Ranges of the Fuselloviridae of Hyperthermophilic Archaea: Implications for Evolution in Extreme Environments

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CRISPR Loci Reveal Networks of Gene Exchange in Archaea Avital Brodt, Mor N Lurie-Weinberger and Uri Gophna*

Brodt et al. Biology Direct 2011, 6:65 http://www.biology-direct.com/content/6/1/65 RESEARCH Open Access CRISPR loci reveal networks of gene exchange in archaea Avital Brodt, Mor N Lurie-Weinberger and Uri Gophna* Abstract Background: CRISPR (Clustered, Regularly, Interspaced, Short, Palindromic Repeats) loci provide prokaryotes with an adaptive immunity against viruses and other mobile genetic elements. CRISPR arrays can be transcribed and processed into small crRNA molecules, which are then used by the cell to target the foreign nucleic acid. Since spacers are accumulated by active CRISPR/Cas systems, the sequences of these spacers provide a record of the past “infection history” of the organism. Results: Here we analyzed all currently known spacers present in archaeal genomes and identified their source by DNA similarity. While nearly 50% of archaeal spacers matched mobile genetic elements, such as plasmids or viruses, several others matched chromosomal genes of other organisms, primarily other archaea. Thus, networks of gene exchange between archaeal species were revealed by the spacer analysis, including many cases of inter-genus and inter-species gene transfer events. Spacers that recognize viral sequences tend to be located further away from the leader sequence, implying that there exists a selective pressure for their retention. Conclusions: CRISPR spacers provide direct evidence for extensive gene exchange in archaea, especially within genera, and support the current dogma where the primary role of the CRISPR/Cas system is anti-viral and anti- plasmid defense. Open peer review: This article was reviewed by: Profs. W. Ford Doolittle, John van der Oost, Christa Schleper (nominated by board member Prof. -

A Virus That Infects a Hyperthermophile Encapsidates A-Form

RESEARCH | REPORTS we observe sets of regulatory sites that exhibit Illumina, Inc. One or more embodiments of one or more patents SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIALS patterns of coordinated regulation (e.g., LYN, and patent applications filed by Illumina may encompass the www.sciencemag.org/content/348/6237/910/suppl/DC1 encoding a tyrosine kinase involved in B cell methods, reagents, and data disclosed in this manuscript. All Materials and Methods methods for making the transposase complexes are described in signaling) (Fig. 4B), although reproducibility of Figs. S1 to S22 (18); however, Illumina will provide transposase complexes in Tables S1 and S2 these patterns across biological replicates was response to reasonable requests from the scientific community References (24–39) modest (fig. S22). Given the sparsity of the data, subject to a material transfer agreement. Some work in this study identifying pairs of coaccessible DNA elements is related to technology described in patent applications 19 March 2015; accepted 24 April 2015 WO2014142850, 2014/0194324, 2010/0120098, 2011/0287435, Published online 7 May 2015; within individual loci is statistically challenging 2013/0196860, and 2012/0208705. 10.1126/science.aab1601 and merits further development. We report chromatin accessibility maps for >15,000 single cells. Our combinatorial cellular indexing scheme could feasibly be scaled to col- VIROLOGY lect data from ~17,280 cells per experiment by using 384-by-384 barcoding and sorting 100 nu- clei per well (assuming similar cell recovery and A virus that infects a collision rates) (fig. S1) (19). Particularly as large- scale efforts to build a human cell atlas are con- templated (23), it is worth noting that because hyperthermophile encapsidates DNA is at uniform copy number, single-cell chro- matin accessibility mapping may require far fewer A-form DNA reads per single cell to define cell types, relative to single-cell RNA-seq. -

Phylogenetics of Archaeal Lipids Amy Kelly 9/27/2006 Outline

Phylogenetics of Archaeal Lipids Amy Kelly 9/27/2006 Outline • Phlogenetics of Archaea • Phlogenetics of archaeal lipids • Papers Phyla • Two? main phyla – Euryarchaeota • Methanogens • Extreme halophiles • Extreme thermophiles • Sulfate-reducing – Crenarchaeota • Extreme thermophiles – Korarchaeota? • Hyperthermophiles • indicated only by environmental DNA sequences – Nanoarchaeum? • N. equitans a fast evolving euryarchaeal lineage, not novel, early diverging archaeal phylum – Ancient archael group? • In deepest brances of Crenarchaea? Euryarchaea? Archaeal Lipids • Methanogens – Di- and tetra-ethers of glycerol and isoprenoid alcohols – Core mostly archaeol or caldarchaeol – Core sometimes sn-2- or Images removed due to sn-3-hydroxyarchaeol or copyright considerations. macrocyclic archaeol –PMI • Halophiles – Similar to methanogens – Exclusively synthesize bacterioruberin • Marine Crenarchaea Depositional Archaeal Lipids Biological Origin Environment Crocetane methanotrophs? methane seeps? methanogens, PMI (2,6,10,15,19-pentamethylicosane) methanotrophs hypersaline, anoxic Squalane hypersaline? C31-C40 head-to-head isoprenoids Smit & Mushegian • “Lost” enzymes of MVA pathway must exist – Phosphomevalonate kinase (PMK) – Diphosphomevalonate decarboxylase – Isopentenyl diphosphate isomerase (IPPI) Kaneda et al. 2001 Rohdich et al. 2001 Boucher et al. • Isoprenoid biosynthesis of archaea evolved through a combination of processes – Co-option of ancestral enzymes – Modification of enzymatic specificity – Orthologous and non-orthologous gene -

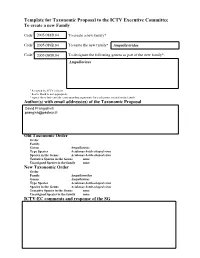

Template for Taxonomic Proposal to the ICTV Executive Committee to Create a New Family

Template for Taxonomic Proposal to the ICTV Executive Committee To create a new Family Code† 2005.088B.04 To create a new family* Code† 2005.089B.04 To name the new family* Ampullaviridae † Code 2005.090B.04 To designate the following genera as part of the new family*: Ampullavirus † Assigned by ICTV officers ° Leave blank is not appropriate * repeat these lines and the corresponding arguments for each genus created in the family Author(s) with email address(es) of the Taxonomic Proposal David Prangishvili [email protected] Old Taxonomic Order Order Family Genus Ampullavirus Type Species Acidianus bottle-shaped virus Species in the Genus Acidianus bottle-shaped virus Tentative Species in the Genus none Unassigned Species in the family none New Taxonomic Order Order Family Ampullaviridae Genus Ampullavirus Type Species Acidianus bottle-shaped virus Species in the Genus Acidianus bottle-shaped virus Tentative Species in the Genus none Unassigned Species in the family none ICTV-EC comments and response of the SG Argumentation to create a new family: We propose classifying the Acidianus bottle-shaped virus as a first representative of a new family because of the unique bottle-shaped morphology of the virion which, to our knowledge, has not previously been observed in the viral world. Moreover, the complex asymmetric virion, lacking elements with icosahedral or regular helical symmetry, with two completely different structures at each end and an envelope encasing a funnel-shaped core represents, as far as we can judge, represents a principally novel type of virus particle. The funnel-shaped core of the enveloped virion consists of three distinct structural units: the “stopper”, the nucleoprotein cone, consisting of double-stranded DNA and DNA-binding proteins, and the inner core. -

The LUCA and Its Complex Virome in Another Recent Synthesis, We Examined the Origins of the Replication and Structural Mart Krupovic , Valerian V

PERSPECTIVES archaea that form several distinct, seemingly unrelated groups16–18. The LUCA and its complex virome In another recent synthesis, we examined the origins of the replication and structural Mart Krupovic , Valerian V. Dolja and Eugene V. Koonin modules of viruses and posited a ‘chimeric’ scenario of virus evolution19. Under this Abstract | The last universal cellular ancestor (LUCA) is the most recent population model, the replication machineries of each of of organisms from which all cellular life on Earth descends. The reconstruction of the four realms derive from the primordial the genome and phenotype of the LUCA is a major challenge in evolutionary pool of genetic elements, whereas the major biology. Given that all life forms are associated with viruses and/or other mobile virion structural proteins were acquired genetic elements, there is no doubt that the LUCA was a host to viruses. Here, by from cellular hosts at different stages of evolution giving rise to bona fide viruses. projecting back in time using the extant distribution of viruses across the two In this Perspective article, we combine primary domains of life, bacteria and archaea, and tracing the evolutionary this recent work with observations on the histories of some key virus genes, we attempt a reconstruction of the LUCA virome. host ranges of viruses in each of the four Even a conservative version of this reconstruction suggests a remarkably complex realms, along with deeper reconstructions virome that already included the main groups of extant viruses of bacteria and of virus evolution, to tentatively infer archaea. We further present evidence of extensive virus evolution antedating the the composition of the virome of the last universal cellular ancestor (LUCA; also LUCA. -

Sulfolobus Acidocaldarius Claus AAGAARD, JACOB Z

Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA Vol. 92, pp. 12285-12289, December 1995 Biochemistry Intercellular mobility and homing of an archaeal rDNA intron confers a selective advantage over intron- cells of Sulfolobus acidocaldarius CLAus AAGAARD, JACOB Z. DALGAARD*, AND ROGER A. GARRETr Institute of Molecular Biology, Copenhagen University, S0lvgade 83 H, 1307 Copenhagen K, Denmark Communicated by Carl R. Woese, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, Urbana, IL, August 28, 1995 ABSTRACT Some intron-containing rRNA genes of ar- experiments suggest, but do not establish, that the intron is chaea encode homing-type endonucleases, which facilitate mobile between yeast cells. intron insertion at homologous sites in intron- alleles. These To test whether the archaeal introns constitute mobile archaeal rRNA genes, in contrast to their eukaryotic coun- elements, we electroporated the intron-containing 23S rRNA terparts, are present in single copies per cell, which precludes gene from the archaeal hyperthermophile Desulfurococcus intron homing within one cell. However, given the highly mobilis on nonreplicating bacterial vectors into an intron- conserved nature of the sequences flanking the intron, hom- culture of Sulfolobus acidocaldarius. In the presence of I-Dmo ing may occur in intron- rRNA genes of other archaeal cells. I, the endonuclease encoded by the D. mobilis intron (20), the To test whether this occurs, the intron-containing 23S rRNA intron was shown to home in the chromosomal DNA of intron- gene of the archaeal hyperthermophile Desulfurococcus mobi- cells of S. acidocaldarius. Moreover, using a double drug- lis, carried on nonreplicating bacterial vectors, was electro- resistant mutant (21), it was demonstrated that the intron can porated into an intron- culture of Sulfolobus acidocaldarius. -

The Isolation of Viruses Infecting Archaea

Portland State University PDXScholar Biology Faculty Publications and Presentations Biology 2010 The Isolation of Viruses Infecting Archaea Kenneth M. Stedman Portland State University Kate Porter Mike L. Dyall-Smith Follow this and additional works at: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/bio_fac Part of the Bacteria Commons, Biology Commons, and the Viruses Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Citation Details Stedman, Kenneth M., Kate Porter, and Mike L. Dyall-Smith. "The isolation of viruses infecting Archaea." Manual of aquatic viral ecology. American Society for Limnology and Oceanography (ASLO) (2010): 57-64. This Article is brought to you for free and open access. It has been accepted for inclusion in Biology Faculty Publications and Presentations by an authorized administrator of PDXScholar. Please contact us if we can make this document more accessible: [email protected]. MANUAL of MAVE Chapter 6, 2010, 57–64 AQUATIC VIRAL ECOLOGY © 2010, by the American Society of Limnology and Oceanography, Inc. The isolation of viruses infecting Archaea Kenneth M. Stedman1, Kate Porter2, and Mike L. Dyall-Smith3 1Department of Biology, Center for Life in Extreme Environments, Portland State University, P.O. Box 751, Portland, OR 97207, USA 2Biota Holdings Limited, 10/585 Blackburn Road, Notting Hill Victoria 3168, Australia 3Max Planck Institute of Biochemistry, Department of Membrane Biochemistry, Am Klopferspitz 18, 82152 Martinsried, Germany Abstract A mere 50 viruses of Archaea have been reported to date; these have been investigated mostly by adapting methods used to isolate bacteriophages to the unique growth conditions of their archaeal hosts. The most numer- ous are viruses of thermophilic Archaea. -

Virus–Host Interactions and Their Roles in Coral Reef Health and Disease

!"#$"%& Virus–host interactions and their roles in coral reef health and disease Rebecca Vega Thurber1, Jérôme P. Payet1,2, Andrew R. Thurber1,2 and Adrienne M. S. Correa3 !"#$%&'$()(*+%&,(%--.#(+''/%!01(1/$%0-1$23++%(#4&,,+5(5&$-%#6('+1#$0$/$-("0+708-%#0$9(&17( 3%+7/'$080$9(4+$#3+$#6(&17(&%-($4%-&$-1-7("9(&1$4%+3+:-10'(70#$/%"&1'-;(<40#(=-80-5(3%+807-#( &1(01$%+7/'$0+1($+('+%&,(%--.(80%+,+:9(&17(->34�?-#($4-(,01@#("-$5--1(80%/#-#6('+%&,(>+%$&,0$9( &17(%--.(-'+#9#$->(7-',01-;(A-(7-#'%0"-($4-(70#$01'$08-("-1$40'2&##+'0&$-7(&17(5&$-%2'+,/>12( &##+'0&$-7(80%+>-#($4&$(&%-(/10B/-($+('+%&,(%--.#6(540'4(4&8-(%-'-08-7(,-##(&$$-1$0+1($4&1( 80%/#-#(01(+3-12+'-&1(#9#$->#;(A-(493+$4-#0?-($4&$(80%/#-#(+.("&'$-%0&(&17(-/@&%9+$-#( 791&>0'&,,9(01$-%&'$(50$4($4-0%(4+#$#(01($4-(5&$-%('+,/>1(&17(50$4(#',-%&'$010&1(C#$+19D('+%&,#($+( 01.,/-1'-(>0'%+"0&,('+>>/10$9(791&>0'#6('+%&,(",-&'401:(&17(70#-&#-6(&17(%--.("0+:-+'4->0'&,( cycling. Last, we outline how marine viruses are an integral part of the reef system and suggest $4&$($4-(01.,/-1'-(+.(80%/#-#(+1(%--.(./1'$0+1(0#(&1(-##-1$0&,('+>3+1-1$(+.($4-#-(:,+"&,,9( 0>3+%$&1$(-180%+1>-1$#; To p - d ow n e f f e c t s Viruses infect all cellular life, including bacteria and evidence that macroorganisms play important parts in The ecological concept that eukaryotes, and contain ~200 megatonnes of carbon the dynamics of viroplankton; for example, sponges can organismal growth and globally1 — thus, they are integral parts of marine eco- filter and consume viruses6,7. -

Supplementary Text S1

1 Supplementary Text S1 2 Dataset of reference viral genomes Viral genome sequences and taxonomic 3 information of viruses and their hosts are based on the GenomeNet/Virus-Host DB 4 (Mihara, et al., 2016). The Virus-Host DB covers viruses with complete genomes stored 5 in RefSeq/viral and GenBank. The sequence and taxonomic data are downloadable at 6 http://www.genome.jp/virushostdb/. Viral genome sequences and taxonomic 7 information used in ViPTree will be updated every few months following Virus-Host 8 DB updates. 9 Calculation of genomic similarity (SG) and proteomic tree The original Phage 10 Proteomic Tree (Rohwer and Edwards, 2002) tested multiple approaches and 11 parameters to calculate genomic distance for evaluation of compatibility between the 12 Phage Proteomic Tree and taxonomical system of the International Committee on 13 Taxonomy of Viruses. In contrast, ViPTree performs proteomic tree calculation based 14 on tBLASTx as reported previously by other several studies (Bellas, et al., 2015; 15 Bhunchoth, et al., 2016; Mizuno, et al., 2013). Specifically, normalized tBLASTx scores 16 (SG; 0 ≤ SG ≤ 1) between viral genomes are calculated as described (Bhunchoth, et al., 17 2016). For simple calculation of SG of segmented viruses, sequences of each segmented 18 viral genome were concatenated into one sequence by inserting a sequence of 100 19 ambiguous nucleotides (N) at each concatenation site. In addition, genome sequences 20 longer than 100 kb are split into each 100 kb fragment just for faster tBLASTx 21 calculation. Genomic distance is calculated as 1−SG. Proteomic tree generation is 22 performed by BIONJ (Gascuel, 1997) based on the genomic distance, using the R 23 package ‘Ape’. -

On the Biological Success of Viruses

MI67CH25-Turner ARI 19 June 2013 8:14 V I E E W R S Review in Advance first posted online on June 28, 2013. (Changes may still occur before final publication E online and in print.) I N C N A D V A On the Biological Success of Viruses Brian R. Wasik and Paul E. Turner Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology, Yale University, New Haven, Connecticut 06520-8106; email: [email protected], [email protected] Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 2013. 67:519–41 Keywords The Annual Review of Microbiology is online at adaptation, biodiversity, environmental change, evolvability, extinction, micro.annualreviews.org robustness This article’s doi: 10.1146/annurev-micro-090110-102833 Abstract Copyright c 2013 by Annual Reviews. Are viruses more biologically successful than cellular life? Here we exam- All rights reserved ine many ways of gauging biological success, including numerical abun- dance, environmental tolerance, type biodiversity, reproductive potential, and widespread impact on other organisms. We especially focus on suc- cessful ability to evolutionarily adapt in the face of environmental change. Viruses are often challenged by dynamic environments, such as host immune function and evolved resistance as well as abiotic fluctuations in temperature, moisture, and other stressors that reduce virion stability. Despite these chal- lenges, our experimental evolution studies show that viruses can often readily adapt, and novel virus emergence in humans and other hosts is increasingly problematic. We additionally consider whether viruses are advantaged in evolvability—the capacity to evolve—and in avoidance of extinction. On the basis of these different ways of gauging biological success, we conclude that viruses are the most successful inhabitants of the biosphere. -

The Stability of Lytic Sulfolobus Viruses

The Stability of Lytic Sulfolobus Viruses A thesis submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Cincinnati In partial fulfillment of The requirements for the degree of Master of Sciences in the Department of Biological Sciences of the College of Arts and Sciences 2017 Khaled S. Gazi B.S. Umm Al-Qura University, 2011 Committee Chair: Dennis W. Grogan, Ph.D. i Abstract Among the three domains of cellular life, archaea are the least understood, and functional information about archaeal viruses is very limited. For example, it is not known whether many of the viruses that infect hyperthermophilic archaea retain infectivity for long periods of time under the extreme conditions of geothermal environments. To investigate the capability of viruses to Infect under the extreme conditions of geothermal environments. A number of plaque- forming viruses related to Sulfolobus islandicus rod-shaped viruses (SIRVs), isolated from Yellowstone National Park in a previous study, were evaluated for stability under different stress conditions including high temperature, drying, and extremes of pH. Screening of 34 isolates revealed a 95-fold range of survival with respect to boiling for two hours and 94-fold range with respect to drying for 24 hours. Comparison of 10 viral strains chosen to represent the extremes of this range showed little correlation of stability with respect to different stresses. For example, three viral strains survived boiling but not drying. On the other hand, five strains that survived the drying stress did not survive the boiling temperature, whereas one strain survived both treatments and the last strain showed low survival of both. -

Insights Into Archaeal Evolution and Symbiosis from the Genomes of a Nanoarchaeon and Its Inferred Crenarchaeal Host from Obsidian Pool, Yellowstone National Park

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Microbiology Publications and Other Works Microbiology 4-22-2013 Insights into archaeal evolution and symbiosis from the genomes of a nanoarchaeon and its inferred crenarchaeal host from Obsidian Pool, Yellowstone National Park Mircea Podar University of Tennessee - Knoxville, [email protected] Kira S. Makarova National Institutes of Health David E. Graham University of Tennessee - Knoxville, [email protected] Yuri I. Wolf National Institutes of Health Eugene V. Koonin National Institutes of Health See next page for additional authors Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_micrpubs Part of the Microbiology Commons Recommended Citation Biology Direct 2013, 8:9 doi:10.1186/1745-6150-8-9 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Microbiology at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Microbiology Publications and Other Works by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Authors Mircea Podar, Kira S. Makarova, David E. Graham, Yuri I. Wolf, Eugene V. Koonin, and Anna-Louise Reysenbach This article is available at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange: https://trace.tennessee.edu/ utk_micrpubs/44 Podar et al. Biology Direct 2013, 8:9 http://www.biology-direct.com/content/8/1/9 RESEARCH Open Access Insights into archaeal evolution and symbiosis from the genomes of a nanoarchaeon and its inferred crenarchaeal host from Obsidian Pool, Yellowstone National Park Mircea Podar1,2*, Kira S Makarova3, David E Graham1,2, Yuri I Wolf3, Eugene V Koonin3 and Anna-Louise Reysenbach4 Abstract Background: A single cultured marine organism, Nanoarchaeum equitans, represents the Nanoarchaeota branch of symbiotic Archaea, with a highly reduced genome and unusual features such as multiple split genes.