DISCUSSION ITEM for Meeting of September 13, 2

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lick Observatory Records: Photographs UA.036.Ser.07

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/c81z4932 Online items available Lick Observatory Records: Photographs UA.036.Ser.07 Kate Dundon, Alix Norton, Maureen Carey, Christine Turk, Alex Moore University of California, Santa Cruz 2016 1156 High Street Santa Cruz 95064 [email protected] URL: http://guides.library.ucsc.edu/speccoll Lick Observatory Records: UA.036.Ser.07 1 Photographs UA.036.Ser.07 Contributing Institution: University of California, Santa Cruz Title: Lick Observatory Records: Photographs Creator: Lick Observatory Identifier/Call Number: UA.036.Ser.07 Physical Description: 101.62 Linear Feet127 boxes Date (inclusive): circa 1870-2002 Language of Material: English . https://n2t.net/ark:/38305/f19c6wg4 Conditions Governing Access Collection is open for research. Conditions Governing Use Property rights for this collection reside with the University of California. Literary rights, including copyright, are retained by the creators and their heirs. The publication or use of any work protected by copyright beyond that allowed by fair use for research or educational purposes requires written permission from the copyright owner. Responsibility for obtaining permissions, and for any use rests exclusively with the user. Preferred Citation Lick Observatory Records: Photographs. UA36 Ser.7. Special Collections and Archives, University Library, University of California, Santa Cruz. Alternative Format Available Images from this collection are available through UCSC Library Digital Collections. Historical note These photographs were produced or collected by Lick observatory staff and faculty, as well as UCSC Library personnel. Many of the early photographs of the major instruments and Observatory buildings were taken by Henry E. Matthews, who served as secretary to the Lick Trust during the planning and construction of the Observatory. -

GEORGE HERBIG and Early Stellar Evolution

GEORGE HERBIG and Early Stellar Evolution Bo Reipurth Institute for Astronomy Special Publications No. 1 George Herbig in 1960 —————————————————————– GEORGE HERBIG and Early Stellar Evolution —————————————————————– Bo Reipurth Institute for Astronomy University of Hawaii at Manoa 640 North Aohoku Place Hilo, HI 96720 USA . Dedicated to Hannelore Herbig c 2016 by Bo Reipurth Version 1.0 – April 19, 2016 Cover Image: The HH 24 complex in the Lynds 1630 cloud in Orion was discov- ered by Herbig and Kuhi in 1963. This near-infrared HST image shows several collimated Herbig-Haro jets emanating from an embedded multiple system of T Tauri stars. Courtesy Space Telescope Science Institute. This book can be referenced as follows: Reipurth, B. 2016, http://ifa.hawaii.edu/SP1 i FOREWORD I first learned about George Herbig’s work when I was a teenager. I grew up in Denmark in the 1950s, a time when Europe was healing the wounds after the ravages of the Second World War. Already at the age of 7 I had fallen in love with astronomy, but information was very hard to come by in those days, so I scraped together what I could, mainly relying on the local library. At some point I was introduced to the magazine Sky and Telescope, and soon invested my pocket money in a subscription. Every month I would sit at our dining room table with a dictionary and work my way through the latest issue. In one issue I read about Herbig-Haro objects, and I was completely mesmerized that these objects could be signposts of the formation of stars, and I dreamt about some day being able to contribute to this field of study. -

Biography of Horace Welcome Babcock

NATIONAL ACADEMY OF SCIENCES H O R ACE W ELCOME B A B COC K 1 9 1 2 — 2 0 0 3 A Biographical Memoir by GEO R G E W . P R ESTON Any opinions expressed in this memoir are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Academy of Sciences. Biographical Memoir COPYRIGHT 2007 NATIONAL ACADEMY OF SCIENCES WASHINGTON, D.C. Photograph by Mount Wilson and Los Campanas Observatories HORACE WELCOME BABCOCK September 13, 1912−August 29, 2003 BY GEORGE W . P RESTON ORACE BABCOCK’S CAREER at the Mount Wilson and Palomar H(later, Hale) Observatories spanned more than three decades. During the first 18 years, from 1946 to 1964, he pioneered the measurement of magnetic fields in stars more massive than the sun, produced a famously successful model of the 22-year cycle of solar activity, and invented important instruments and techniques that are employed throughout the world to this day. Upon assuming the directorship of the observatories, he devoted his last 14 years to creating one of the world’s premier astronomical observatories at Las Campanas in the foothills of the Chilean Andes. CHILDHOOD AND EDUCATION Horace Babcock was born in Pasadena, California, the only child of Harold and Mary Babcock. Harold met Horace’s mother, Mary Henderson, in Berkeley during his student days at the College of Electrical Engineering, University of California. After brief appointments as a laboratory assis- tant at the National Bureau of Standards in 1906 and as a physics teacher at the University of California, Berkeley, in 1907, Horace’s father was invited by George Ellery Hale in 1908 to join the staff of the Mount Wilson Observatory (MWO), where he remained for the rest of his career. -

Lick Observatory Records: Business Records UA.036.Ser.02

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/c8x92grd No online items Guide to the Lick Observatory Records: Business records UA.036.Ser.02 Alix Norton University of California, Santa Cruz 2015 1156 High Street Santa Cruz 95064 [email protected] URL: http://guides.library.ucsc.edu/speccoll Guide to the Lick Observatory UA.036.Ser.02 1 Records: Business records UA.036.Ser.02 Language of Material: English Contributing Institution: University of California, Santa Cruz Title: Lick Observatory Records: Business records Creator: Lick Observatory Identifier/Call Number: UA.036.Ser.02 Physical Description: 83.0 Linear Feet115 boxes, 16 oversize boxes, 2 rolls, 4 flat file drawers Date (inclusive): 1870-2002 Date (bulk): 1888-1960 Access Collection is open for research. Arrangement Materials in the business records series are arranged alphabetically by subject or topic, then chronologically. Historical note The Lick Observatory was completed in 1888 and continues to be an active astronomy research facility at the summit of Mount Hamilton, near San Jose, California. It is named after James Lick (1796-1876), who left $700,000 in 1875 to purchase land and build a facility that would be home to "a powerful telescope, superior to and more powerful than any telescope yet made". The completion of the Great Lick Refractor in 1888 made the observatory home to the largest refracting telescope in the world for 9 years, until the completion of the 40-inch refractor at Yerkes Observatory in 1897. Since its founding in 1887, the Lick Observatory facility has provided on-site housing on Mount Hamilton for researchers, their families, and staff, making it the world's oldest residential observatory. -

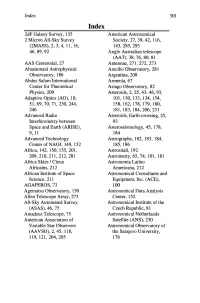

Index 2Df Galaxy Survey, 135 2 Micron All-Sky Survey (2MASS), 2

Index 301 Index 2dF Galaxy Survey, 135 American Astronornical 2 Micron All-Sky Survey Society, 27, 39, 42, 116, (2MASS), 2, 3, 4, 11, 16, 143,285,293 46,89,92 Anglo Australian telescope (AAT), 38, 76, 80, 81 AAS Centennial, 27 Antennae, 271, 272, 273 Abastumani Astrophysical Arecibo Observatory, 281 Observatory, 186 Argentina, 208 Abdus Salam International Armenia, 67 Center for Theoretical Asiago Observatory, 82 Physics, 209 Asteroids, 2, 25, 43, 46, 93, Adaptive Optics (AO), 10, 101, 130, 133, 134, 154, 51,69, 70,71,230,244, 158, 162, 178, 179, 180, 246 181,183,184,206,231 Advanced Radio Asteroids, Earth-crossing, 25, Interferometry between 93 Space and Earth (ARISE), Asteroseismology, 45, 178, 9, 11 184 Advanced Technology Astrographs, 182, 183, 184, Center of NAOJ, 149, 152 185, 186 Africa, 142, 150, 155, 201, Astrositall, 192 209,210,211,212,281 Astrometry, 65, 74, 101, 181 Africa Skies 1 Cieux Astronornia Latina Africains, 212 Americana, 212 African Institute of Space Astronornical Consultants and Science, 211 Equipment, Inc. (ACE), AGAPEROS, 73 100 Agematsu Observatory, 150 Astronornical Data Analysis Allen Telescope Array, 273 Center, 152 All-Sky Automated Survey Astronornical Institute of the (ASAS), 46, 75 Czech Republic, 81 Amadeus Telescope, 75 Astronomical Netherlands American Association of Satellite (ANS), 230 V ariable Star Observers Astronornical Observatory of (AAVSO), 2, 45, 118, the Sarajevo University, 119,121,204,205 178 302 Astronomical Society of the BASIC STAMP Pacific, 116, 122, 123, 285 Microprocessors, 275 -

The Day We Found the Universe / Marcia Bartusiak

ALSO BY MARCIA BARTUSIAK Thursday's Universe Through a Universe Darkly Einstein's Unfinished Symphony Archives of the Universe To Steve The center of my universe, who shared every light-year along the way Contents Preface / January 1, 1925 Setting Out 1. The Little Republic of Science 2. A Rather Remarkable Number of Nebulae 3. Grander Than the Truth 4. Such Is the Progress of Astronomy in the Wild and Wooly West 5. My Regards to the Squashes 6. It Is Worthy of Notice Exploration 7. Empire Builder 8. The Solar System Is Off Center and Consequently Man Is Too 9. He Surely Looks Like the Fourth Dimension! 10. Go at Each Other “Hammer and Tongs” 11. Adonis 12. On the Brink of a Big Discovery—or Maybe a Big Paradox Discovery 13. Countless Whole Worlds…Strewn All Over the Sky 14. Using the 100-Inch Telescope the Way It Should Be Used 15. Your Calculations Are Correct, but Your Physical Insight Is Abominable 16. Started Off with a Bang Whatever Happened to… Notes Acknowledgments Bibliography Preface January 1, 1925 he twenties were not just roaring, they were blazing. Moviegoers were flocking to the cinema to watch in amazement as T Moses parted the Red Sea in Cecil B. DeMille's silent film epic The Ten Commandments, Greece overthrew its monarchy and proclaimed itself a republic, the first dinosaur eggs were discovered in Mongolia's Gobi Desert, and crossword puzzles became all the rage. It was the height of the Jazz Age, when Victorian ideals came tumbling down in a frenzy of flappers, Freudian analysis, and abstract art. -

Lick Observatory Volunteer Orientation Packet

Lick Observatory Volunteer Orientation Packet Elinor Gates with contributions from Lotus Baker, Ron Bricmont, Paul Lynam, Patricia Madison, Rem Stone, John Wareham, and Lick Observatory Volunteers May 15, 2018 Contents 1 When to Arrive 2 2 Evening Schedules 3 2.1 ScheduleofTelescopeObjects . ... 3 2.2 EveningwiththeStarsNights . 4 2.3 MusicoftheSpheresNights . 5 3 Nightly Assignments 5 4 Telescope Traffic Flow 7 4.1 36”Refractor ................................... 7 4.2 40”Reflector ................................... 9 4.3 Other ....................................... 10 5 Observatory and Telescope Facts 10 5.1 General ...................................... 10 5.2 36”Refractor ................................... 11 5.3 40”Reflector ................................... 12 5.4 OtherSourcesofInformation . 13 6 Frequently Asked Questions 13 7 How Do Telescopes Work? 14 8 What’s New at Lick Observatory? 14 9 Interacting with the Public 16 1 10 Safety and Emergencies 19 10.1General ...................................... 19 10.2911Emergencies ................................. 19 10.3LaserPointers................................... 20 11 Fundraisers 20 11.1 VisitorCenterServices . 20 12 Volunteer Orientation and Appreciation Nights 20 13 Other Volunteer Opportunities at Lick Observatory 21 13.1 ExpandedVisitorServices . 21 13.2 HistoricalCollections . 21 13.3Other ....................................... 21 1 When to Arrive It takes one hour to drive to Lick Observatory from downtown San Jose without traffic problems, please plan accordingly. Table -

Historyofthetelescope

HISTORY OF THE TELESCOPE PEDRO RÉ http://www.astrosurf.com/re CONTENTS JOSEPH VON FRAUNHOFER (1787 - 1826) AND THE GREAT DORPAT REFRACTOR ......................................... 3 ALVAN CLARK (1804-1887), GEORGE BASSETT CLARK (1827-1891) AND ALVAN GRAHAM CLARK (1832- 1897): AMERICAN MAKERS OF TELESCOPE OPTICS ................................................................................ 13 WILLIAM PARSONS (1800-1867) E O LEVIATÃ DE PARSONSTOWN .......................................................... 21 THE 25-INCH NEWALL REFRACTOR...................................................................................................... 29 O TELESCÓPIO DE CRAIG (1852) ........................................................................................................ 35 O GRANDE TELESCÓPIO DE MELBOURNE ............................................................................................. 41 O GRANDE REFRACTOR DA EXPOSIÇÃO DE PARIS (1900) ...................................................................... 51 THE 36-INCH CROSSLEY REFLECTOR ................................................................................................... 61 BUILDING LARGE TELESCOPES: I- REFRACTORS ...................................................................................... 69 BUILDING LARGE TELESCOPES: II- REFLECTORS ..................................................................................... 77 THE SPECTROHELIOGRAPH AND THE SPECTROHELISCOPE ........................................................................ 93 RUSSELL -

The Grubb Contribution to Telescope Technology

THE GRUBB CONTRIBUTION TO TELESCOPE TECHNOLOGY I.S. Glass South African Astronomical Observatory, Observatory 7935 , South Africa ABSTRACT For almost 100 years the Grubbs of Dublin, Ireland, were famous for the telescopes they supplied to observatories worldwide. Two generations of the family dominated this unusual enterprise. Their success can be attributed to innovative engineering, often introduced at the urging of their most demanding customers. Thomas Grubb (1800-1898) was encouraged to become a telescope maker by Romney Robinson of Armagh Observatory. Rigid heavy mountings characterized his instruments and made them relatively vibration-free. Early in his career he mounted a Cauchoix lens in what was briefly to be the world’s largest refractor (Markree). He went on to supply instruments to the Royal Greenwich Observatory in England and the West Point Military Academy in the United States, among others. His innovative mirror support system was adopted by the Earl of Rosse for his giant reflectors. Howard Grubb (1844-1931), the younger son of Thomas, was responsible with his father for the Great Melbourne Telescope and later on his own for the 27-inch telescope at the K & K Observatory, Vienna. A talented engineer, he made many improvements to telescope controls, drive motors and mountings. As a skilled optician, he ground and polished many large lenses including some of the first wide-angle photographic objectives. The history of the firm has been documented by Glass (1997) and Manville (1971). EARLY DAYS OF THE FIRM Thomas Grubb grew up as a member of the Quaker community in Waterford, Southeast Ireland. Many of the local Quakers were entrepreneurs operating in the fields of engineering and shipbuilding. -

Heber Doust Curtis and the Island Universe Theory

Fort Hays State University FHSU Scholars Repository Master's Theses Graduate School Spring 2011 Heber Doust Curtis And The slI and Universe Theory Hyrum Austin Somers Fort Hays State University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholars.fhsu.edu/theses Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Somers, Hyrum Austin, "Heber Doust Curtis And The slI and Universe Theory" (2011). Master's Theses. 157. https://scholars.fhsu.edu/theses/157 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at FHSU Scholars Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of FHSU Scholars Repository. Heber Doust Curtis and the Island Universe Theory being A Thesis Presented to the Graduate Faculty of the Fort Hays State University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts by Hyrum Austin Somers B.A., Fort Hays State University Date_______________________ Approved___________________________ Major Professor Approved____________________________ Chair, Graduate Council ABSTRACT The beginning of the twentieth century was a time a great change and development within American astronomy. The period is rife with astronomers, both men and women, who advanced the discipline. However, few historians have looked at the lives of these astronomers. When an astronomer is chosen for closer study, they tend to be one who contributed to the astronomical discipline with a significant discovery. Unfortunately, those astronomers whose careers did not climax with discovery have a tendency to be forgotten by historians, even though their lives and research have affected our modern understanding. This thesis looks at one such astronomer named Heber Doust Curtis. -

The 36-Inch Crossley Reflector

THE 36-INCH CROSSLEY REFLECTOR PEDRO RÉ http://astrosurf.com/re The 36-inch Crossley Reflector was used by James Edward Keeler (1857-1900) during the last two years of his short productive scientific life for a systematic and epoch making astrophotographic study of diffuse, planetary and “spiral” nebulae. Keeler became one of the first astronomers to successfully use large reflecting telescopes in the United States. This telescope was built by Andrew Ainslie Common (1841-1903), a wealthy engineer and amateur astronomer of Ealing, London. Common commissioned a 36-inch silver-on-glass mirror from George Calver (1834 - 1927) and mounted it in 1879 as a newtonian with a fork mount. Common used this instrument mainly as a photographic telescope. Several photographs of the Orion nebulae were obtained with considerable success. In 1883, Common produced images that showed for the first time, stars that were not seen by visual observers (Figure 1). Figure 1- Andrew Ainslie Common (left), 36-inch reflector (center), M 42 photograph obtained in 1883 (right). Figure 2- 36-inch Crossley reflector (left) and iron dome (right). 1 The telescope was sold to Edward Crossley (1841-1901) in 1885. Crossley, also a British amateur astronomer, installed it in Halifax (Yorkshire, England). Crossley designed and constructed a dome to house the telescope. This iron covered dome was almost 40 feet in diameter and weighted 15 tons. It was moved by a water engine (one full turn lasting 5 min). Heat exchange was minimized by a clever system of water pipes running on the ground of the observatory. There was also an elevated platform for the observer (Figure 2). -

James E.Keeler's Photographs of Nebulae and Clusters

JAMES E. KEELER’S PHOTOGRAPHS OF NEBULAE AND CLUSTERS MADE WITH THE CROSSLEY REFLECTOR Pedro Ré http://www.astrosurf.com/re Edward Keeler (1857-1900) used the 36-inch Crossley Reflector during the last two years of his short productive scientific life for a systematic and epoch making astrophotographic study of diffuse, planetary and “spiral” nebulae. Keeler became one of the first astronomers to successfully use large reflecting telescopes in the United States 1. Keeler initiated an extended program of nebular photography showing for the first time that a great majority of these objects exhibited a spiral structure2. After Keeler’s death, Charles Dillon Perrine (1867-1951) completed the project and renewed the telescope completely between 1902 and 1904. The original open tube and mount were replaced with a much more rigid closed tube on an English equatorial mount 3. Perrine improved the mount, mechanical drive and gears. He also removed the secondary mirror and mounted the plate-holder directly at the prime focus of the telescope. A clever system of prisms and lenses were also installed so that the observer could guide during the long exposures directly from an eyepiece outside the telescope tube. In this way the Crossley reflector became a much faster and efficient instrument for direct nebular photography. These first successful photographic results obtained with this telescope helped to establish the reflector as the preferred observatory instrument. After Keeler’s death in 1900, his colleagues at Lick Observatory arranged for the publication of his and Perrine’s photographs of nebulae and clusters in a special volume of the Lick Observatory publications 4.