Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Annual Report 2018 CONTENTS PAGE

Hearing and Sight Care Caithness and North West Sutherland Annual Report 2018 CONTENTS PAGE Page 1 Organisation Information Page 2 & 3 Chairman’s Report Page 4 Manager’s Report Pages 5 & 6 2017-2018 Business Plan – Progress Report Pages 7 & 8 2018-2019 Business Plan Page 9 Outside Memberships Appendices 1. 2016/17 – 2017/18 Regular Services Provided including referrals and visits 2. Report and Financial Statement to 31st March 2018 3. Funding Sources 4. Organisation Profile Company Number SC 217561 Charity Number SC 027221 Board Members (See Appendices 2 and 4) Chairman Mr Roy MacKenzie Vice Chairman Mr William Ather Treasurer Mr Ewen Macdonald Company Secretary & Manager Mrs Deirdre Aitken Independent Examiner Mr John Cormack Victor T Fraser & Company Chartered Accountants Market Place WICK Caithness KW1 4LP Bankers The Royal Bank of Scotland plc 1 Bridge Street WICK Caithness KW1 4BU Registered Office The Sensory Centre 23 Telford Street WICK tel/fax: 01955 606170 Caithness e-mail: [email protected] KW1 5EQ Website: www.sensorycentre.org.uk Other addresses The Sensory Centre 9 Riverside Place THURSO tel/fax: 01847 895636 Caithness e-mail: [email protected] KW14 8BZ Website: www.sensorycentre.org.uk 1 Chairman’s Report 2018 General Since my last report, the main focus has been on completing the HSC policy review, including the update to the Data Protection Policy to reflect the requirements of the implementation of the General Data Protection Regulations. We have recently received a communication from NHS Highland suggesting a contract variation relating to the scope of our current contract. I have been reviewing how our board operates against the latest guidance and good practice for Charity Trustees published by the Scottish Charity Regulator, OSCR. -

Rosehall Information

USEFUL TELEPHONE NUMBERS Rosehall Information POLICE Emergency = 999 Non-emergency NHS 24 = 111 No 21 January 2021 DOCTORS Dr Aline Marshall and Dr Scott Smith PLEASE BE AWARE THAT, DUE TO COVID-RELATED RESTRICTIONS Health Centre, Lairg: tel 01549 402 007 ALL TIMES LISTED SHOULD BE CHECKED Drs C & J Mair and Dr S Carbarns This Information Sheet is produced for the benefit of all residents of Creich Surgery, Bonar Bridge: tel 01863 766 379 Rosehall and to welcome newcomers into our community DENTISTS K Baxendale / Geddes: 01848 621613 / 633019 Kirsty Ramsey, Dornoch: 01862 810267; Dental Laboratory, Dornoch: 01862 810667 We have a Village email distribution so that everyone knows what is happening – Golspie Dental Practice: 01408 633 019; Sutherland Dental Service, Lairg: 402 543 if you would like to be included please email: Julie Stevens at [email protected] tel: 07927 670 773 or Main Street, Lairg: PHARMACIES 402 374 (freephone: 0500 970 132) Carol Gilmour at [email protected] tel: 01549 441 374 Dornoch Road, Bonar Bridge: 01863 760 011 Everything goes out under “blind” copy for privacy HOSPITALS / Raigmore, Inverness: 01463 704 000; visit 2.30-4.30; 6.30-8.30pm There is a local residents’ telephone directory which is available from NURSING HOMES Lawson Memorial, Golspie: 01408 633 157 & RESIDENTIAL Wick (Caithness General): 01955 605 050 the Bradbury Centre or the Post Office in Bonar Bridge. Cambusavie Wing, Golspie: 01408 633 182; Migdale, Bonar Bridge: 01863 766 211 All local events and information can be found in the -

Midnight Train to Georgemas Report Final 08-12-2017

Midnight Train to Georgemas 08/12/2017 Reference number 105983 MIDNIGHT TRAIN TO GEORGEMAS MIDNIGHT TRAIN TO GEORGEMAS MIDNIGHT TRAIN TO GEORGEMAS IDENTIFICATION TABLE Client/Project owner HITRANS Project Midnight Train to Georgemas Study Midnight Train to Georgemas Type of document Report Date 08/12/2017 File name Midnight Train to Georgemas Report v5 Reference number 105983 Number of pages 57 APPROVAL Version Name Position Date Modifications Claire Mackay Principal Author 03/07/2017 James Consultant Jackson David Project 1 Connolly, Checked Director 24/07/2017 by Alan Director Beswick Approved David Project 24/07/2017 by Connolly Director James Principal Author 21/11/2017 Jackson Consultant Alan Modifications Director Beswick to service Checked 2 21/11/2017 costs and by Project David demand Director Connolly forecasts Approved David Project 21/11/2017 by Connolly Director James Principal Author 08/12/2017 Jackson Consultant Alan Director Beswick Checked Final client 3 08/12/2017 by Project comments David Director Connolly Approved David Project 08/12/2017 by Connolly Director TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION 6 2. BACKGROUND INFORMATION 6 2.1 EXISTING COACH AND RAIL SERVICES 6 2.2 CALEDONIAN SLEEPER 7 2.3 CAR -BASED TRAVEL TO /FROM THE CAITHNESS /O RKNEY AREA 8 2.4 EXISTING FERRY SERVICES AND POTENTIAL CHANGES TO THESE 9 2.5 AIR SERVICES TO ORKNEY AND WICK 10 2.6 MOBILE PHONE -BASED ESTIMATES OF CURRENT TRAVEL PATTERNS 11 3. STAKEHOLDER CONSULTATION 14 4. PROBLEMS/ISSUES 14 4.2 CONSTRAINTS 16 4.3 RISKS : 16 5. OPPORTUNITIES 17 6. SLEEPER OPERATIONS 19 6.1 INTRODUCTION 19 6.2 SERVICE DESCRIPTION & ROUTING OPTIONS 19 6.3 MIXED TRAIN OPERATION 22 6.4 TRACTION & ROLLING STOCK OPTIONS 25 6.5 TIMETABLE PLANNING 32 7. -

Far North Line Review Team Consolidation Report August 2019

Far North Line Review Team Consolidation Report “It is essential we make the most of this important asset for passengers, for sustainable freight transport, and for the communities and businesses along the whole route.” Fergus Ewing, 16 December 2016 August 2019 Remit Fergus Ewing MSP, Cabinet Secretary for Rural Economy, established the Far North Line Review Team in December 2016 with a remit to identify potential opportunities to improve connectivity, operational performance and journey time on the line. Membership The Review Team comprised senior representatives from the railway industry (Transport Scotland, Network Rail, ScotRail) as well as relevant stakeholders (HITRANS, Highland Council, HIE, Caithness Transport Forum and Friends of the Far North Line). The Team has now concluded and this report reviews the Team’s achievements and sets out activities and responsibilities for future years. Report This report provides a high-level overview of achievements, work-in-progress and future opportunities. Achievements to date: Safety and Improved Journey Time In support of safety and improved journey time we: 1. Implemented Stage 1 of Level Crossing Upgrade by installing automatic barrier prior to closing the crossing by 2024. 2. Upgraded two level crossings to full barriers. 3 4 3. Started a programme of improved animal 6 6 fencing and removed lineside vegetation to 6 reduce the attractiveness of the line to livestock and deer. 4. Established six new full-time posts in Helmsdale to address fencing and vegetation issues along the line. 1 5. Removed the speed restriction near Chapelton Farm to allow a linespeed of 75mph. 6. Upgraded open level crossing operations at 2 Brora, Lairg and Rovie to deliver improved line speed and a reduction in the end to end 5 journey time Achievements to date: Customer service improvements 2 2 In support of improved customer service we 2 2 1. -

Caithness and Sutherland Proposed Local Development Plan Committee Version November, 2015

Caithness and Sutherland Proposed Local Development Plan Committee Version November, 2015 Proposed CaSPlan The Highland Council Foreword Foreword Foreword to be added after PDI committee meeting The Highland Council Proposed CaSPlan About this Proposed Plan About this Proposed Plan The Caithness and Sutherland Local Development Plan (CaSPlan) is the second of three new area local development plans that, along with the Highland-wide Local Development Plan (HwLDP) and Supplementary Guidance, will form the Highland Council’s Development Plan that guides future development in Highland. The Plan covers the area shown on the Strategy Map on page 3). CaSPlan focuses on where development should and should not occur in the Caithness and Sutherland area over the next 10-20 years. Along the north coast the Pilot Marine Spatial Plan for the Pentland Firth and Orkney Waters will also influence what happens in the area. This Proposed Plan is the third stage in the plan preparation process. It has been approved by the Council as its settled view on where and how growth should be delivered in Caithness and Sutherland. However, it is a consultation document which means you can tell us what you think about it. It will be of particular interest to people who live, work or invest in the Caithness and Sutherland area. In preparing this Proposed Plan, the Highland Council have held various consultations. These included the development of a North Highland Onshore Vision to support growth of the marine renewables sector, Charrettes in Wick and Thurso to prepare whole-town visions and a Call for Sites and Ideas, all followed by a Main Issues Report and Additional Sites and Issues consultation. -

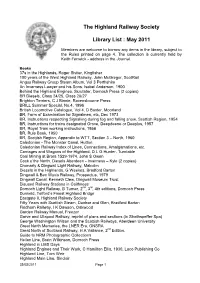

Library List : May 2011

The Highland Railway Society Library List : May 2011 Members are welcome to borrow any items in the library, subject to the Rules printed on page 4. The collection is currently held by Keith Fenwick - address in the Journal. Books 37s in the Highlands, Roger Siviter, Kingfisher 100 years of the West Highland Railway, John McGregor, ScotRail Angus Railway Group Steam Album, Vol 3 Perthshire An Inverness Lawyer and his Sons, Isabel Anderson, 1900 Behind the Highland Engines, Scrutator, Dornoch Press (2 copies) BR Diesels, Class 24/25, Class 26/27 Brighton Terriers, C J Binnie, Ravensbourne Press BRILL Summer Special, No.4, 1996 British Locomotive Catalogue, Vol 4, D Baxter, Moorland BR, Form of Examination for Signalmen, etc, Dec 1973 BR, Instructions respecting Signalling during fog and falling snow, Scottish Region, 1954 BR, Instructions for trains designated Grove, Deepdeene or Deeplus, 1957 BR, Royal Train working instructions, 1956 BR, Rule Book, 1950 BR, Scottish Region, Appendix to WTT, Section 3 – North, 1960 Caledonian - The Monster Canal, Hutton Caledonian Railway Index of Lines, Connections, Amalgamations, etc. Carriages and Wagons of the Highland, D L G Hunter, Turntable Coal Mining at Brora 1529-1974, John S Owen Cock o’the North, Diesels Aberdeen - Inverness – Kyle (2 copies) Cromarty & Dingwall Light Railway, Malcolm Diesels in the Highlands, G Weekes, Bradford Barton Dingwall & Ben Wyvis Railway, Prospectus, 1979 Dingwall Canal, Kenneth Clew, Dingwall Museum Trust Disused Railway Stations in Caithness Dornoch Light Railway, B Turner, 2nd, 3rd, 4th editions, Dornoch Press Dunkeld, Telford’s Finest Highland Bridge Eastgate II, Highland Railway Society Fifty Years with Scottish Steam, Dunbar and Glen, Bradford Barton Findhorn Railway, I K Dawson, Oakwood Garden Railway Manual, Freezer Garve and Ullapool Railway, reprint of plans and sections (in Strathspeffer Spa) George Washington Wilson and the Scottish Railways, Aberdeen University Great North Memories, the LNER Era, GNSRA Great North of Scotland Railway, H A Vallance, 2nd Edition. -

Service Tain - Brora X25 Monday - Friday (Not Bank Holidays)

Service Tain - Brora X25 Monday - Friday (not Bank Holidays) Operated by: HI Stagecoach Highlands Timetable valid from 27 Sep 2021 until further notice Service: X25 X25 X25 X25 X25 X25 X25 X25 X25 Notes: XPrd1 Prd2 Operator: HI HI HI HI HI HI HI HI HI Days: MThPX Tain, Post Office Depart: 05:34 08:35 09:30 11:30 12:30 14:25 15:23 17:31 18:36 Dornoch, Cathedral Square 05:50 08:50 09:45 11:45 12:45 14:40 15:38 17:46 18:51 Poles, Hotel 05:55 .... .... .... .... .... .... .... .... Golspie, Bank of Scotland 06:05 .... .... .... .... .... .... .... .... Brora, Station Square Arrive: 06:14 .... .... .... .... .... .... .... .... MThPX Monday to Thursday, period only (not Bank Hols) XPrd1 Does not operate on these dates: 27/09/2021 to 30/09/2021 04/10/2021 to 07/10/2021 25/10/2021 to 28/10/2021 01/11/2021 to 04/11/2021 08/11/2021 to 11/11/2021 15/11/2021 to 18/11/2021 22/11/2021 to 25/11/2021 29/11/2021 to 02/12/2021 06/12/2021 to 09/12/2021 13/12/2021 to 16/12/2021 20/12/2021 to 22/12/2021 06/01/2022 to 06/01/2022 10/01/2022 to 13/01/2022 17/01/2022 to 20/01/2022 24/01/2022 to 27/01/2022 31/01/2022 to 03/02/2022 07/02/2022 to 10/02/2022 14/02/2022 to 17/02/2022 24/02/2022 to 24/02/2022 28/02/2022 to 03/03/2022 07/03/2022 to 10/03/2022 14/03/2022 to 17/03/2022 21/03/2022 to 24/03/2022 28/03/2022 to 31/03/2022 19/04/2022 to 21/04/2022 25/04/2022 to 28/04/2022 02/05/2022 to 05/05/2022 09/05/2022 to 12/05/2022 16/05/2022 to 19/05/2022 23/05/2022 to 26/05/2022 30/05/2022 to 02/06/2022 06/06/2022 to 09/06/2022 13/06/2022 to 16/06/2022 20/06/2022 -

Brora Caravan Club Site

Welcome to Brora Caravan Club Site Get to know Brora This site on the east coast of Sutherland is set in a sheltered saucer of land just 300 yards from a safe, sandy beach, where Arctic Tern nest just above the waterline. You can play golf directly from the site and use the course as your pathway to the sandy beach close by. It’s a site to unwind on, with marvellous walking and birdwatching to be had in the area and sea or loch fishing too. Watching is a way of life here with Arctic Terns, seals, dolphins and deer to order. To see the spectacular scenery of the region you can walk, drive or cycle along quiet routes and discover the many picturesque lochs and mountains. The single-track rail journey to Wick is a scenic must and the Orkney Islands beckon with day trips from John O’Groats, which are feasible from Brora during the summer. Things to see and do from this Club Site Local attractions • Cawdor Castle • Dunrobin Castle This Castle, with its medieval tower and drawbridge, contains a fine The Castle, home of Clan Sutherland, dates from the 15th Century collection of paintings, tapestries, furniture, books and porcelain. and contains magnificent silver, family portraits and tapestries. There are 3 beautiful gardens - the flower garden, the wild garden Beautiful, formal gardens. Falconry displays daily. The museum and the newly-restored walled garden. contains Pictish stones and a collection of stuffed animals and birds. 01667 404401 01408 633177 www.cawdorcastle.com www.dunrobincastle.co.uk • Tain Through Time • Timespan Visitor Centre A museum, visitor centre and medieval church in a beautiful The North’s most exciting and multi awardwinning heritage centre churchyard setting. -

Come Walk in the Footsteps of Your Ancestors

Come walk in the footsteps of your ancestors Come walk in the footsteps Your Detailed Itinerary of your ancestors Highland in flavour. Dunrobin Castle is Museum is the main heritage centre so-called ‘Battle of the Braes’ a near Golspie, a little further north. The for the area. The scenic spectacle will confrontation between tenants and Day 1 Day 3 largest house in the northern Highlands, entrance you all the way west, then police in 1882, which was eventually to Walk in the footsteps of Scotland’s The A9, the Highland Road, takes you Dunrobin and the Dukes of Sutherland south, for overnight Ullapool. lead to the passing of the Crofters Act monarchs along Edinburgh’s Royal speedily north, with a good choice of are associated with several episodes in in 1886, giving security of tenure to the Mile where historic ‘closes’ – each stopping places on the way, including the Highland Clearances, the forced crofting inhabitants of the north and with their own story – run off the Blair Castle, and Pitlochry, a popular emigration of the native Highland Day 8 west. Re-cross the Skye Bridge and main road like ribs from a backbone. resort in the very centre of Scotland. people for economic reasons. Overnight continue south and east, passing Eilean Between castle and royal palace is a Overnight Inverness. Golspie or Brora area. At Braemore junction, south of Ullapool, Donan Castle, once a Clan Macrae lifetime’s exploration – so make the take the coastal road for Gairloch. This stronghold. Continue through Glen most of your day! Gladstone’s Land, section is known as ‘Destitution Road’ Shiel for the Great Glen, passing St Giles Cathedral, John Knox House Day 4 Day 6 recalling the road-building programme through Fort William for overnight in are just a few of the historic sites on that was started here in order to provide Ballachulish or Glencoe area. -

Luxury Hotel & Restaurant

LUXURY HOTEL & RESTAURANT BESPOKE ELEGANT INTIMATE “As both a golfer and a salmon fisherman, and with Links House placed amongst some of the best rivers and courses in the country, I have just found my new Highland hideaway.” A Links House Guest Review, Tripadvisor WELCOME Links House at Royal Dornoch is about a journey to create a perfect locale, a perfect retreat and a perfect experience. The Links House experience extends well beyond golf. Our sincere hope is we afford you the opportunity to look deeper into the Highlands. Yes there is amazingly charming, strategic golf here but there is also stunning history, country sport, wildlife, restaurants, people, coastlines and so much more. Here you can feel the history of the Highlands in your bones, smell the ages in the cool, seaside air, view the purple heather upon the mountains and taste spring in the scent of whin bloom. It is about being ‘in the moment’ for more than just a moment. Enjoy early morning journal writing at your bedroom desk, quiet afternoon tea in our sitting room, single malt at sunset on our putting green, and tranquil evenings reading by the fire in our library. If it is country sport and activities you seek we offer an abundance of the highest quality - perhaps the finest links golf in the world - as well as cycling, fishing, hiking, riding, shooting, stalking and walking. Like the river’s claim on the salmon’s heart, these are the reasons to return to Links House year after year. So come visit, feel the history, play this wondrous course and experience the Highlands. -

Hiking Scotland's

Hiking Scotland’s North Highlands & Isle of Lewis July 20-30, 2021 (11 days | 15 guests) with archaeologist Mary MacLeod Rivett Archaeology-focused tours for the curious to the connoisseur. Clachtoll Broch Handa Island Arnol Dun Carloway (5.5|645) (6|890) BORVE Great Bernera & Traigh Uige 3 Caithness Dunbeath(4.5|425) (6|870) Stornoway (5|~) 3 3 BRORA Glasgow Isle of Lewis Callanish Lairg Standing Stones Ullapool (4.5|~) (4.5|885) Ardvreck LOCHINVER Castle Inverness Little Assynt # Overnight stays Itinerary stops Scottish Flights Hikes (miles|feet) Highlands Ferry Archaeological Institute of America Lecturer & Host Dr. Mary MacLeod oin archaeologist Mary MacLeod Rivett and a small group of like- Rivett was born in minded travelers on this 11-day tour of Scotland’s remote north London, England, to J Highlands and the Isle of Lewis in the Outer Hebrides. Mostly we a Scottish-Canadian family. Her father’s will explore off the well-beaten Highland tourist trail, and along the way family was from we will be treated to an abundance of archaeological and historical sites, Scotland’s Outer striking scenery – including high cliffs, sea lochs, sandy and rocky bays, Hebrides, and she mountains, and glens – and, of course, excellent hiking. spent a lot of time in the Hebrides as a child. Mary earned her Scotland’s long and varied history stretches back many thousands of B.A. from the University of Cambridge, years, and archaeological remains ranging from Neolithic cairns and and her M.A. from the University of stone circles to Iron Age brochs (ancient dry stone buildings unique to York. -

Notes of A9 Safety Group Meeting on 18 April 2019

A9 Safety Group 18th April 2019 at 11:00 Tulloch Caledonian Stadium, Inverness. Marco Bardelli Transport Scotland Donna Turnbull Transport Scotland Stuart Wilson Transport Scotland Richard Perry Transport Scotland David McKenzie Transport Scotland Sam McNaughton Transport Scotland Chris Smith A9 Luncarty to Birnam, Transport Scotland Michael McDonnell Road Safety Scotland Kenny Sutherland Northern Safety Camera Unit Martin Reid Road Haulage Association Fraser Grieve Scottish Council for Development & Industry David Richardson Federation of Small Businesses Alan Campbell BEAR Scotland Ltd Kevin McKechnie BEAR Scotland Ltd Notes of Meeting 1. Welcome & Introductions. Stuart Wilson welcomed all to the meeting followed by a round table introduction from everybody present. Stuart Wilson provided high level accident and casualty trends on the A9 and identified that sustaining the momentum in accident reduction activity was still a key priority but that driving down accident numbers was very challenging. He elaborated that fatigue on the A9 was a serious issue and any measures which could reduce accident risk associated with fatigue should be considered. 2. Apologies Apologies were made for Morag MacKay (TS), Aaron Duncan (SCP), Chic Haggart (PKC) 3. Previous Minutes and Actions The minutes were accepted as a true reflection of the previous meeting. SW and DT are continuing to investigate the research that would be required to allow the consideration of a change to the national speed limit for vans and will provide an update on this at future meetings Action: Transport Scotland will consider the research required to determine the impact of a change to the national speed limits for vans. 4. Average Speed Camera System Update.