Moncure Conway: Abolitionist, Reformer

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Frederick Douglass

Central Library of Rochester and Monroe County · Historic Monographs Collection AMERICAN CRISIS BIOGRAPHIES Edited by Ellis Paxson Oberholtzer, Ph. D. Central Library of Rochester and Monroe County · Historic Monographs Collection Zbe Hmcrican Crisis Biographies Edited by Ellis Paxson Oberholtzer, Ph.D. With the counsel and advice of Professor John B. McMaster, of the University of Pennsylvania. Each I2mo, cloth, with frontispiece portrait. Price $1.25 net; by mail» $i-37- These biographies will constitute a complete and comprehensive history of the great American sectional struggle in the form of readable and authoritative biography. The editor has enlisted the co-operation of many competent writers, as will be noted from the list given below. An interesting feature of the undertaking is that the series is to be im- partial, Southern writers having been assigned to Southern subjects and Northern writers to Northern subjects, but all will belong to the younger generation of writers, thus assuring freedom from any suspicion of war- time prejudice. The Civil War will not be treated as a rebellion, but as the great event in the history of our nation, which, after forty years, it is now clearly recognized to have been. Now ready: Abraham Lincoln. By ELLIS PAXSON OBERHOLTZER. Thomas H. Benton. By JOSEPH M. ROGERS. David G. Farragut. By JOHN R. SPEARS. William T. Sherman. By EDWARD ROBINS. Frederick Douglass. By BOOKER T. WASHINGTON. Judah P. Benjamin. By FIERCE BUTLER. In preparation: John C. Calhoun. By GAILLARD HUNT. Daniel Webster. By PROF. C. H. VAN TYNE. Alexander H. Stephens. BY LOUIS PENDLETON. John Quincy Adams. -

Theodore Parker's Man-Making Strategy: a Study of His Professional Ministry in Selected Sermons

Loyola University Chicago Loyola eCommons Dissertations Theses and Dissertations 1993 Theodore Parker's Man-Making Strategy: A Study of His Professional Ministry in Selected Sermons John Patrick Fitzgibbons Loyola University Chicago Follow this and additional works at: https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_diss Part of the Literature in English, North America Commons Recommended Citation Fitzgibbons, John Patrick, "Theodore Parker's Man-Making Strategy: A Study of His Professional Ministry in Selected Sermons" (1993). Dissertations. 3283. https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_diss/3283 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses and Dissertations at Loyola eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Loyola eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 License. Copyright © 1993 John Patrick Fitzgibbons Theodore Parker's Man-Making Strategy: A Study of His Professional Ministry in Selected Sermons by John Patrick Fitzgibbons, S.J. A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate School of Loyola University of Chicago in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Chicago, Illinois May, 1993 Copyright, '°1993, John Patrick Fitzgibbons, S.J. All rights reserved. PREFACE Theodore Parker (1810-1860) fashioned a strategy of "man-making" and an ideology of manhood in response to the marginalization of the professional ministry in general and his own ministry in particular. Much has been written about Ralph Waldo Emerson (1803-1882) and his abandonment of the professional ministry for a literary career after 1832. Little, however, has been written about Parker's deliberate choice to remain in the ministry despite formidable opposition from within the ranks of Boston's liberal clergy. -

American Liberal Pacifists and the Memory of Abolitionism, 1914-1933 Joseph Kip Kosek

American Liberal Pacifists and the Memory of Abolitionism, 1914-1933 Joseph Kip Kosek Americans’ memory of their Civil War has always been more than idle reminiscence. David Blight’s Race and Reunion: The Civil War in American Memory is the best new work to examine the way that the nation actively reimagined the past in order to explain and justify the present. Interdisciplinary in its methods, ecumenical in its sources, and nuanced in its interpretations, Race and Reunion explains how the recollection of the Civil War became a case of race versus reunion in the half-century after Gettysburg. On one hand, Frederick Douglass and his allies promoted an “emancipationist” vision that drew attention to the role of slavery in the conflict and that highlighted the continuing problem of racial inequality. Opposed to this stance was the “reconciliationist” ideal, which located the meaning of the war in notions of abstract heroism and devotion by North and South alike, divorced from any particular allegiance. On this ground the former combatants could meet undisturbed by the problems of politics and ideological difference. This latter view became the dominant memory, and, involving as it did a kind of forgetting, laid the groundwork for decades of racial violence and segregation, Blight argues. Thus did memory frame the possibilities of politics and moral action. The first photograph in Race and Reunion illustrates this victory of reunion, showing Woodrow Wilson at Gettysburg in 1913. Wilson, surrounded by white veterans from North and South, with Union and Confederate flags flying, is making a speech in which he praises the heroism of the combatants in the Civil War while declaring their “quarrel forgotten.” The last photograph in Blight’s book, though, invokes a different story about Civil War memory. -

Xerox University Microfilms 300 North Zeeb Road Ann Arbor, Michigan 48106 I I 75-3032

INFORMATION TO USERS This material was produced from a microfilm copy of the original document. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the original submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or patterns which may appear on this reproduction. 1. The sign or "target" for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is "Missing Page(s)". If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting thru an image and duplicating adjacent pages to insure you complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a large round black mark, it is an indication that the photographer suspected that the copy may have moved during exposure and thus cause a blurred image. You will find a good image of the page in the adjacent frame. 3. When a map, drawing or chart, etc., was part of the material being photographed the photographer followed a definite method in "sectioning" the material. It is customary to begin photoing at the upper left hand corner of a large sheet and to continue photoing from left to right in equal sections with a small overlap. If necessary, sectioning is continued again — beginning below the first row and continuing on until complete. 4. The majority of users indicate that the textual content is of greatest value, however, a somewhat higher quality reproduction could be made from "photographs" if essential to the understanding of the dissertation. -

1900. Frank P

ANNUAL REPORTS OF THE OFFICERS OF THE TOWN OF BEDFORD, FOR THE FINANCIAL YEAR EN DING FEBRUARY 1, 1901. BOSTON : R. H. BLODGETT & CO. Printers 30 Bromfield Street 1901 3 TOWN OFFICERS 1900-1901. School Committee. ERN BST H . Hos lilER, Term exp ires 1903. G. I ,001,11s, Term expires Selectmen. ELIHU 1902. MRS. M ARY E. LAWS, Term expires 1901. EDW1-N H . BLA KE. T erm expires 1903- . FREDERlC P ARKER, T erm expires 1902 . 1901 Trusues of the Bedford Free Public Library. A llTHUll H. P ARKER, T erm expires • G EORGE R. BLINN, Term expires 190'1. A BR.l. ld E . BROWN, Term expires 1903. Fence Viewers. ARTHUR H. P ARKER- ELIHU G . LoOMIS, Term expires 1902. FREDElllC PARKER. EDWIN H. BLAKE. CHARLES w. JENKS, Term expires 1901. .Assessors. A ls o the a cting pastors of the th ree churches, together with the chairman of Board of Select men a nd chairman of t he School C ommittee. "ILLIAM G . HARTWBLL, T erm expires 1903- . ""'2 \,, L. H oDGOON Term expires lvv, · IRVI NG • G L NE T erm expires 1001. Shawsheen Cemetery Commitue. WILLIS · A • G EORGE R. BLINN, T erm expires 1903. Ocerseer~ of Poor. C HARLES w. JENKS, Term expires 1901. A BRAM E. BROWN, T erm expires 1902. HARTWELL, Term expires 1903- . l90'l B H umns Term ex pires · \.V ILLIAM . ' \" SPREDBY T erm expires l 901 . Constables. J AM ES ••· ' E DWARD WALSH. J OSEPH ll. MCFARLAND. QUINCY S. COLE. Town Clerk and TreaBUrer. Funeral Undertaker. • C W..llLES A. -

Prodigal Sons and Daughters: Unitarianism In

Gaw 1 Prodigal Sons and Daughters: Unitarianism in Philadelphia, 1796 -1846 Charlotte Gaw Senior Honors Thesis Swarthmore College Professor Bruce Dorsey April 27, 2012 Gaw2 Table of Contents Acknowledgements ....................................................................................... 3 Introduction: Building A Church ...................................................................................... .4 Chapter One: Atlantic Movements Confront a "National" Establishment ........................ 15 Chapter Two: Hicksites as Unitarians ................................................................. .45 Chapter Three: Journeys Toward Liberation ............................................................ 75 Epilogue: A Prodigal Son Returns ..................................................................... 111 Bibliography ................................................................................................. 115 Gaw3 Acknow ledgements First, I want to thank Bruce Dorsey. His insight on this project was significant and valuable at every step along the way. His passion for history and his guidance during my time at Swarthmore have been tremendous forces in my life. I would to thank Eugene Lang for providing me summer funding to do a large portion of my archival research. I encountered many people at the Historical Society of Pennsylvania, the Library Company of Philadelphia, the American Philosophical Society, and the Friends Historical Library who were eager and willing to help me in the research process, specifically -

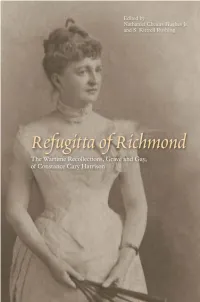

The Wartime Recollections, Grave and Gay, of Constance Cary Harrison / Edited, Annotated, and with an Introduction by Nathaniel Cheairs Hughes Jr

Refugitta of Richmond RefugittaThe Wartime Recollections, of Richmond Grave and Gay, of Constance Cary Harrison Edited by Nathaniel Cheairs Hughes Jr. and S. Kittrell Rushing The University of Tennessee Press • Knoxville a Copyright © 2011 by The University of Tennessee Press / Knoxville. All Rights Reserved. Manufactured in the United States of America. First Edition. Originally published by Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1916. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Harrison, Burton, Mrs., 1843–1920. Refugitta of Richmond: the wartime recollections, grave and gay, of Constance Cary Harrison / edited, annotated, and with an introduction by Nathaniel Cheairs Hughes Jr. and S. Kittrell Rushing. — 1st ed. p. cm. Originally published under title: Recollections grave and gay. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1911. Includes bibliographical references and index. eISBN-13: 978-1-57233-792-3 eISBN-10: 1-57233-792-3 1. Harrison, Burton, Mrs., 1843–1920. 2. United States—History—Civil War, 1861–1865—Personal narratives, Confederate. 3. Virginia—History—Civil War, 1861–1865—Personal narratives, Confederate. 4. United States—History—Civil War, 1861–1865—Women. 5. Virginia—History—Civil War, 1861–1865—Women. 6. Richmond (Va.)—History—Civil War, 1861–1865. I. Hughes, Nathaniel Cheairs. II. Rushing, S. Kittrell. III. Harrison, Burton, Mrs., 1843-1920 Recollections grave and gay. IV. Title. E487.H312 2011 973.7'82—dc22 20100300 Contents Preface ............................................. ix Acknowledgments .....................................xiii -

Southern Women and Their Families in the 19Th Century: Papers and Diaries

A Guide to the Microfilm Edition of Research Collections in Women’s Studies General Editors: Anne Firor Scott and William H. Chafe Southern Women and Their Families in the 19th Century: Papers and Diaries Consulting Editor: Anne Firor Scott Series D, Holdings of the Virginia Historical Society Part 2: Richmond, Virginia Associate Editor and Guide Compiled by Martin P. Schipper A microfilm project of UNIVERSITY PUBLICATIONS OF AMERICA An Imprint of CIS 4520 East-West Highway • Bethesda, MD 20814-3389 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Southern women and their families in the 19th century, papers and diaries. Series D, Holdings of the Virginia Historical Society [microform] / consulting editor, Anne Firor Scott ; [associate editor, Martin P. Schipper]. microfilm reels. — (Research collections in women’s studies) Accompanied by printed guide compiled by Martin P. Schipper, entitled: A guide to the microfilm edition of Southern women and their families in the 19th century, papers and diaries. Series D, Holdings of the Virginia Historical Society. ISBN 1-55655-532-6 (pt. 2 : microfilm) 1. Women—Virginia—History—19th century—Sources. 2. Family— Virginia—History—19th century—Sources. I. Scott, Anne Firor, 1921– . II. Schipper, Martin Paul. III. Virginia Historical Society. IV. University Publications of America (Firm) V. Title: Guide to the microfilm edition of Southern women and their families in the 19th century, papers and diaries. Series D, Holdings of the Virginia Historical Society. VI. Series. [HQ1458] 305.4' 09755' 09034—dc20 -

Friendship, Crisis and Estrangement: U.S.-Italian Relations, 1871-1920

FRIENDSHIP, CRISIS AND ESTRANGEMENT: U.S.-ITALIAN RELATIONS, 1871-1920 A Ph.D. Dissertation by Bahar Gürsel Department of History Bilkent University Ankara March 2007 To Mine & Sinan FRIENDSHIP, CRISIS AND ESTRANGEMENT: U.S.-ITALIAN RELATIONS, 1871-1920 The Institute of Economics and Social Sciences of Bilkent University by BAHAR GÜRSEL In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in THE DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY BILKENT UNIVERSITY ANKARA March 2007 I certify that I have read this thesis and have found that it is fully adequate, in scope and in quality, as a thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History. --------------------------------- Asst. Prof. Dr. Timothy M. Roberts Supervisor I certify that I have read this thesis and have found that it is fully adequate, in scope and in quality, as a thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History. --------------------------------- Asst. Prof. Dr. Nur Bilge Criss Examining Committee Member I certify that I have read this thesis and have found that it is fully adequate, in scope and in quality, as a thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History. --------------------------------- Asst. Prof. Dr. Edward P. Kohn Examining Committee Member I certify that I have read this thesis and have found that it is fully adequate, in scope and in quality, as a thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History. --------------------------------- Asst. Prof. Dr. Oktay Özel Examining Committee Member I certify that I have read this thesis and have found that it is fully adequate, in scope and in quality, as a thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History. -

The Paradox of Theodore Parker: Transcendentalist, Abolitionist, and White Supremacist

Georgia State University ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University History Theses Department of History Fall 12-16-2015 The Paradox of Theodore Parker: Transcendentalist, Abolitionist, and White Supremacist Jim Kelley Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/history_theses Recommended Citation Kelley, Jim, "The Paradox of Theodore Parker: Transcendentalist, Abolitionist, and White Supremacist." Thesis, Georgia State University, 2015. https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/history_theses/98 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of History at ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in History Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE PARADOX OF THEODORE PARKER: TRANSCENDENTALIST, ABOLITIONIST, AND WHITE SUPREMACIST. by JIM KELLEY Under the Direction of David Sehat, Phd ABSTRACT Theodore Parker was one of the leading intellectuals and militant abolitionists of the antebellum era who has been largely overlooked by modern scholars. He was a leading Transcendentalist intellectual and was also one of the most militant leaders of the abolitionist movement. Despite his fervent abolitionism, his writings reveal an attitude that today we would call racist or white supremacist. Some scholars have argued that Parker's motivation for abolishing slavery was to redeem the Anglo-Saxon race from the sin of slavery. I will dispute this claim and explore Parker's true understanding of race. How he could both believe in the supremacy of the white race, and at the same time, militantly oppose African slavery. Parker was influenced by the racial "science" of his era which supported the superiority of the Caucasian race. -

Documenting Women's Lives

Documenting Women’s Lives A Users Guide to Manuscripts at the Virginia Historical Society A Acree, Sallie Ann, Scrapbook, 1868–1885. 1 volume. Mss5:7Ac764:1. Sallie Anne Acree (1837–1873) kept this scrapbook while living at Forest Home in Bedford County; it contains newspaper clippings on religion, female decorum, poetry, and a few Civil War stories. Adams Family Papers, 1672–1792. 222 items. Mss1Ad198a. Microfilm reel C321. This collection of consists primarily of correspondence, 1762–1788, of Thomas Adams (1730–1788), a merchant in Richmond, Va., and London, Eng., who served in the U.S. Continental Congress during the American Revolution and later settled in Augusta County. Letters chiefly concern politics and mercantile affairs, including one, 1788, from Martha Miller of Rockbridge County discussing horses and the payment Adams's debt to her (section 6). Additional information on the debt appears in a letter, 1787, from Miller to Adams (Mss2M6163a1). There is also an undated letter from the wife of Adams's brother, Elizabeth (Griffin) Adams (1736–1800) of Richmond, regarding Thomas Adams's marriage to the widow Elizabeth (Fauntleroy) Turner Cocke (1736–1792) of Bremo in Henrico County (section 6). Papers of Elizabeth Cocke Adams, include a letter, 1791, to her son, William Cocke (1758–1835), about finances; a personal account, 1789– 1790, with her husband's executor, Thomas Massie; and inventories, 1792, of her estate in Amherst and Cumberland counties (section 11). Other legal and economic papers that feature women appear scattered throughout the collection; they include the wills, 1743 and 1744, of Sarah (Adams) Atkinson of London (section 3) and Ann Adams of Westham, Eng. -

Resisting the Slavocracy: the Boston Vigilance Committee's Role in the Creation of the Republican Party, 1846-1860

RESISTING THE SLAVOCRACY: THE BOSTON VIGILANCE COMMITTEE’S ROLE IN THE CREATION OF THE REPUBLICAN PARTY, 1846-1860 by Yasmin K. McGee A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of The Dorothy F. Schmidt College of Arts and Letters In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts Florida Atlantic University Boca Raton, FL May 2020 Copyright 2020 by Yasmin K. McGee ii RESISTING THE SLAVOCRACY: THE BOSTON VIGILANCE COMMITTEE'S ROLE IN THE CREATION OF THE REPUBLICAN PARTY, 1846-1860 April 16th, 2020 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I’d like to put a spin on the familiar proverb “it takes a village,” for me it “took a village” to write this thesis. The village chief, Dr. Stephen Engle, guided me throughout the MA program and as my thesis advisor, with great leadership, insight, understanding, and impressive, yet humble, expertise. I thank Dr. Engle for introducing me to the Boston Vigilance Committee and for encouraging me to undertake this work. Dr. Engle’s love for 19th century American history, depicted through his enthusiasm for teaching, has inspired me to continuously improve my writing and understanding of history. His inspiration and confidence in my work has fostered clear convictions about my own capabilities, yet he has set an example of how to remain modest and strive for further knowledge. My gratitude to Dr. Engle goes beyond words and I am grateful for having been able to learn from him. Dr. Norman has been especially positive and helpful throughout my time in the program. While taking her graduate seminar, she introduced me to the wonders of public and oral history and encouraged me to obtain valuable experience as an intern in a local South Florida museum.