The Early Middle Palaeolithic of Britain

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

HNL Appraisal Package 2 Pinn and Cannon Brook Initial Assessment Plus Document

FINAL HNL Appraisal Package 2 Pinn and Cannon Brook Initial Assessment Plus Document The Environment Agency March 2018 HNL Appraisal Package 2 Pinn and Cannon Brook IA plus document Quality information Prepared by Checked by Approved by Andy Mkandla Steve Edwards Fay Bull Engineer, Water Associate Director, Water Regional Director, Water Laura Irvine Graduate Engineer, Water Stacey Johnson Graduate Engineer, Water Revision History Revision Revision date Details Authorized Name Position Distribution List # Hard Copies PDF Required Association / Company Name Prepared for: The Environment Agency AECOM HNL Appraisal Package 2 Pinn and Cannon Brook IA plus document Prepared for: The Environment Agency Prepared by: Andy Mkandla Engineer E: [email protected] AECOM Infrastructure & Environment UK Limited Royal Court Basil Close Derbyshire Chesterfield S41 7SL UK T: +44 (1246) 209221 aecom.com © 2018 AECOM Infrastructure & Environment UK Limited. All Rights Reserved. This document has been prepared by AECOM Infrastructure & Environment UK Limited (“AECOM”) for sole use of our client (the “Client”) in accordance with generally accepted consultancy principles, the budget for fees and the terms of reference agreed between AECOM and the Client. Any information provided by third parties and referred to herein has not been checked or verified by AECOM, unless otherwise expressly stated in the document. No third party may rely upon this document without the prior and express written agreement of AECOM. Prepared for: The Environment Agency AECOM HNL -

Land at Yiewsley & West Drayton

TOWN AND COUNTRY PLANNING ACT 1990 STOPPING UP OF HIGHWAY (LAND AT YIEWSLEY & WEST DRAYTON LEISURE CENTRE ROWLHEYS PLACE, WEST DRAYTON) ORDER 2020 Made 2020 The London Borough of Hillingdon makes this Order in exercise of its powers under section 247 of the Town and Country Planning Act 1990 (“the Act “), and all other powers enabling it in that behalf: 1. The London Borough of Hillingdon authorises the stopping up of an area of the highway described in the Schedule to the Order and shown hatched blue on the attached Plan, in order to enable development to be carried out in accordance with the planning permission granted under Part III of the Act by the London Borough of Hillingdon on 27 April 2020 under application reference 75127/APP/2019/3221. 2. Where immediately before the date of this Order there is any apparatus of statutory undertakers under, in, on, over, along or across any highway authorised to be stopped up pursuant to this Order then, subject to section 261(4) of the Act those undertakers shall have the same rights as respects that apparatus after that highway is stopped up as they had immediately beforehand. 3. In this Order: “Plan” means the plan at appendix 1 marked 3478- ROWH-ICS-M2-C-Stopping Up signed by authority of the Deputy Chief Executive and Corporate Director of Resident Services and deposited at the London Borough of Hillingdon offices at Main Reception, Civic Centre, High Street, Uxbridge UB8 1UW. 4. This Order shall come into force on the date on which notice that it has been made is first published in accordance with section 252(10) of the Act, and may be cited as the “Stopping up of Highway (land at Yiewsley & West Drayton Leisure Centre Rowlheys Place, West Drayton) Order 2020”. -

01708522666 Trusted Greenford 24HR Commercial Coffee Machine Engineers UB8 Denham UB9 Walk in Refrigertor Installation UB10 Ickenham UB18 Harmondsworth

01708522666 Trusted Greenford 24HR Commercial Coffee Machine Engineers UB8 Denham UB9 Walk In Refrigertor Installation UB10 Ickenham UB18 Harmondsworth We're THAMES WATER APPROVED plumber We are GAS SAFE (CORGI) REGISTERED plumbing, heating, gas engineers We have electrical NICEIC contractors available to you 24 HRS a day 7 days a week We are new RATIONAL SELF COOKING CATERING WHITE EFFICIENCY COMBI OVEN,COOKER APPROVED engineers We repair, maintain, service and install all commercial – domestic gas, commercial catering appliances, commercial – domestic air-conditioning, refrigeration, commercial laundry appliances services, commercial - domestic air-conditioning sytem, commercial - domestic refrigeration & freezer , commercial - domestic LPG , commercial – domestic heating, plumbing and multi trade services to all types of commercial and residential customers. All of our services are offered to types of customers. We offer various types of professional commercial services to all different types of trades customers and residential customers Commercial Air-Conditioning Repair, Air-Conditioning Installation & Ventilation Services - Air Conditioning installations -Air conditioning maintenance and repair - Domestic air-conditioning - Commercial Installations - Office Air Conditioning - Domestic Installations, Home Air Conditioning - Office commercial Air-Conditioning repair and installation - Portable Air Conditioners - R22 Gas Replacement on Air Conditioning - Air-con Gas Refill - Refrigeration Gas Refill - Air-conditioning engineer - Air-con -

West Drayton Waterside

WEST DRAYTON WATERSIDE PHASE ONE, HORTON ROAD, WEST DRAYTON UB7 8EA A UNIQUE CANAL SIDE DEVELOPMENT OF 1, 2 & 3 BEDROOM APARTMENTS R 0 G K 0 K K K C INVEST IN THE CROSS RAIL EFFECT WITH A NEW URBAN LIFESTYLE AT WEST DRAYTON WATERSIDE WITHIN 8 MINUTES OF HEATHROW AND 23 MINUTES OF THE WEST END West Hayes & Ealing Bond Drayton Harlington Southall Hanwell Broadway Street Farringdon Whitechapel Heathrow West Acton Paddington Tottenham Liverpool Canary Ealing Main Line Court Road Street Wharf • Canary Wharf 37 minutes. • Liverpool Street 30 minutes. • Paddington in 23 minutes. WEST DRAYTON WATERSIDE HORTON ROAD EXISTING PROPERTIES HOMES DESIGNED BY BLOCK A AWARD WINNING ARCHITECTS BLOCK C FUTURE PHASE BRIGHT AND LIGHT dual aspect 1, 2 & 3 bedroom apartments set in a private gated development with secure parking - most apartments benefiting from either the luxury of private conveyed gardens or balconies plus access to miles of canal-sidewalks, all designed to encourage an al fresco lifestyle. FUTURE BLOCK B The developments open and green amenity areas bring a new dimension to DEVELOPMENT FUTURE PHASE Metro living. Internally there will be a high specification to match your lifestyle. Clearview Homes are leading exponents of a cutting edge construction technology which creates exceedingly ‘green’ homes that are temperate, tranquil and economic to run. GRAND UNION CANAL ACCESS TO MILES OF CANAL-SIDE WALKS ARE DESIGNED TO ENCOURAGE AN ALFRESCO LIFESTYLE OPEN AND GREE N AMENITY AREAS BRING A NEW DIMENSION TO METRO LIVING WEST DRAYTON WATERSIDE A.G.2 A.G.3 B A.G.1 A.G.4 DINING BEDROOM 1 AREA W BEDROOM 1 GROUND FLOOR CONVEYED GARDEN AREAS BEDROOM 2 A.G.2 KITCHEN W KITCHEN A.G.3 LOUNGE EN- LOUNGE EN- SUITE SUITE DINING HALL LIN. -

RUISLIP, NORTHWOOD and EASTCOTE Local History Society Journal 1999

RUISLIP, NORTHWOOD AND EASTCOTE Local History Society Journal 1999 CONTENTS Re! Author Page Committee Members 2 Lecture Programme 1999-2000 2 Editorial -''" 9911 Catlins Lane, Eastcote Karen Spink 4 9912 The Missing Link: A Writer at South Hill Farm Karen Spink 7 99/3 HaIlowell Rd: A Street Research Project Denise Shackell 12 99/4 Plockettes to Eastcote Place Eileen M BowIt 16 99/5 Eastcote Cottage: The Structure Pat A Clarke 21 99/6 A Middlesex Village: Northwood in 1841 Colleen A Cox 25 9917 Eastcote in the Thirties Ron Edwards 29 99/8 The D Ring Road Problem RonEdwards 32 99/9 Long Distance Rail Services in 1947 Simon Morgan 35 99/10 Ruislip Bowls Club: The Move to Manor Farm, 1940 Ron Lightning 37 99111 RNELHS: Thirty-five Years RonEdwards 38 Cover picture: South Hill Farm, Eastcote by Denise Shackell Designed and edited by Simon Morgan. LMA Research: Pam Morgan Copyright © 1999 individual authors and RNELHS. Membership of the Ruislip, Northwood and Eastcote Local History Society is open to all who are interested in local history. For further information please enquire at a meeting of the Society or contact the Secretary. Meetings are held on the third Monday of each month from September to April and are open to visitors. (Advance booking is required for the Christmas social.) The programme jar 1999-2000 is on page 2. An active Research Group supports those who are enquinng into or wishing to increase our understanding of the history of the ancient parish of Ruislip (the present Ruislip, Northwood and Eastcote). -

Yiewsley Autumn 2017

intouch With YIEWSLEY Conservatives Autumn 2017 Improvements for Yiewsley & West Drayton Artist Impression The railway bridge in Yiewsley & West Drayton is to be transformed following lobbying by Yiewsley and West Drayton Conservative Councillors over many months. Recently we were able to have the bridge cleaned and now we can announce that there has been agreement by the Council’s decision makers to go further and transform the tired looking bridge into one that reflects our rapidly improving area. As the image shows, the transformation will enhance our towns, adding to the benefits of being in Conservative controlled Hillingdon. We are also delighted to say that the railway entrance will be completely altered to provide not just a better visual experience on arrival but it will open up views of the canal, one of our hidden treasures. Alan Deville, a long term resident summed it up, “ I am delighted to hear that the Yiewsley/West Drayton area of our Borough is being improved and that our Conservative councillors are winning support to make changes for the better. And still our Council Tax remains frozen”. Making Yiewsley Safer Cllr Ahmad-Wallana and local residents from Yiewsley High Street have secured funding to help install alley gates to flats that were suffering from littering, fly-tipping and other anti-social behaviour. He said: “Your councillors are here to support local residents and the Council’s Chrysalis fund is available to help secure privately owned alleyways against trespassing and anti-social behaviour.” Mr Power said “Our councillors have been very helpful to us and we will feel much safer when the gates are installed. -

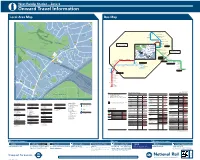

West Ruislip Station – Zone 6 I Onward Travel Information Local Area Map Bus Map

West Ruislip Station – Zone 6 i Onward Travel Information Local Area Map Bus Map 39 O N E AT S 17 R ACRE 56 C St. Martin’s 15 O L D P R I O R Y H SOUTHCOTE RISE 444 10 A Church R 50 47 D C 35 L H O Southcote 12 S I E E Clinic G U n 31 S n A K i N N E O H E E P S L A T H V r A R P A S H S e iv T 76 48 8 T R S R R H E 28 U A 1 D E 3 36 5 A 9 H O T R H R E N N O F A E I M 1 T L E 25 20 G L E 53 D A N 24 L R L 80 I 19 I L M S H A N O E R R O A D E 25 U S 19 N E H 20 O S E C L A E V 33 G R A TA 9 O T P F C H I S E FIELD CLOSE L 3 C D W L R 60 A 3 A Y U River Pinn N H Y A E C W 2 D L E I 96 F A D R O 12 16 28 D ’ S 27 A R 11 17 D W G E K I N Ruislip Heathfield Rise/Glenhurst Avenue 33 71 34 F I E R D ’ S R O A D L D N G E D WA W K I U10 AY E E 21 35 S 45 N I 15 A R Heathfield Rise Woodville Gardens L L King Edwards L Hill Lane L I L H 31 Medical Centre I 48 H Field Way E Y U A W H I L L R I S E N S 2 H ’ Ruislip E R C Westcote Rise Orchard Close V 15 A O N A M 1 Golf Course H C R 20 Manor Road U 15 H Southcote Rise 120 20 C Sharps Lane D A S 1 H O Sharps Lane Neats Acre Ruislip A R Ruislip R P Methodist S M 87 Golf Course A L H Church Ruislip A E N N I CK 33 Golf Course E 36 Ruislip High Street/The Oaks The Orchard, Premier Inn Ruislip Ruislip High Street/Midcroft The yellow tinted area includes every S H D bus stop up to one-and-a-half miles A A Ruislip High Street/Brickwall Lane R RO Ruislip P M Ruislip 44 from West Ruislip. -

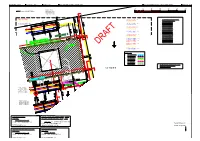

68. Iver Grid SS

Drawn By: NMM Checked : MN Scale 1:50 Iver Grid Sub Station - Layout Plan Iver to Hillingdon 66 kV Cable Replacement Page No. 68 5m 0m 5m 10m 15m 20m 25m Joint Bay Co-ordinates Towards 66kV GIS Building E:504,329.40 N183,498.75 E:504,330.07 N183,495.92 E:504,339.85 N183.498.14 E:504,339.18 N183,501.05 H Red Phase (Iver - Uxbridge 3 - Joint) E: 504,334.54 N: 183,531.00 Red Phase (Iver - Uxbridge 2 - Joint) · For ABB Installed Circuit(s) Cross Section(s) - E: 504,335.55 N: 183,507.50 Yellow Phase (Iver - Uxbridge 3 - Joint) I-U3 Refer to the following Drawing(s) -: Yellow Phase (Iver - Uxbridge 2 - Joint) · Section A-A - PN/CSED/1125 E: 504,334.68 N: 183,530.26 ℄ E: 504,335.95 N: 183,507.06 · Section B-B - PN/CSED/1128 Blue Phase (Iver - Uxbridge 3 - Joint) Blue Phase (Iver - Uxbridge 2 - Joint) Section C-C - PN/CSED/1124 E: 504,334.81 N: 183,529.12 E: 504,336.00 N: 183,506.09 · · Section D-D - PN/CSED/1127 Iver - Uxbridge 3 (Red Phase) · Section E-E - PN/CSED/1126 Red Phase (Iver - Uxbridge 4 - Joint) Iver - Uxbridge 3 (Yellow Phase) Uxbridge 3 E: 504,336.07 N:183,506.25 · Section F-F - PN/CSED/1195 · Section G-G - PN/CSED/1196 Yellow Phase (Iver - Uxbridge 4 - Joint) Iver - Uxbridge 3 (Blue Phase) E: 504,336.17 N: 183,505.71 · Section H-H - PN/CSED/1197 Blue Phase (Iver - Uxbridge 4 - Joint) · Section J-J - PN/CSED/1198 E: 504,336.25, N: 183,505.37 · Section K-K - PN/CSED/1227 · Section L- L - PN/CSED/1263 ℄ Red Phase (Iver - Hillingdon 2 - Joint) · Section M-M - PN/CSED/1264 I-U3 E: 504,334.30 N: 183,497.48 · Section N-N - PN/CSED/1265 -

Roads Task Force Improvements Map 2014

Better Junctions Site Locations TfL’s Business Plan includes provision for substantial cycle infrastructure improvements at 33 proposed locationsWATFORDWATF OacrossRD London. CCHORLEYWOODHORLEYWOOD BBOREHAMWOODOREHAMWOOD LLOUGHTONOUGHTON Major Projects Site Locations BARNETBARNET TfL’s Business PlanRRICKMANSWORTHICKM includesANSWORTH provision for significantBUSHEY improvements to your SSOUTHGATEOUTHGATE CCHINGFORDHINGFORD BBRENTWOODRENTWOOD streets, including the 17 proposed locations shown across London. EEASTAST BBARNETARNET CHIGWELL SSTANMORETANMORE 9 EEDMONTONDMONTON Better Junctions Site Locations EEDGWAREDGWARE FRIERNFRIERN BARNETBARNET WWOODFORDOODFORD 1 Aldgate Gyratory NNORTHWOODORTHWOOD WWOODOOD GGREENREEN 2 Apex Junction 5 (part of Shoreditch Triangle) TTOTTENHAMOTTENHAM WWALTHAMSTOWALTHAMSTOW PINNER 3 Archway Gyratory HENDON RROMFORDOMFORD HHARROWARROW HORNSEY 4 Blackfriars WWANSTEADANSTEAD 5 Borough High Street / RRUISLIPUISLIP 12 HHORNCHURCHORNCHURCH Tooley Street Junction 3 4 13 UUPMINSTERPMINSTER 6 Bow Roundabout LLEYTONEYTON IILFORDLFORD HAMPSTEADHAMPSTEAD 7 Chiswick Roundabout / 17 SSTOKETOKE NNEWINGTONEWINGTON IISLINGTONSLINGTON Kew Bridge Junction WEMBLEY NORTHOLTNORTHOLT WILLESDEN 11 HHACKNEYACKNEY 25 DDAGENHAMAGENHAM 8 Elephant & Castle Northern 27 CAMDENCAMDEN TOWNTOWN SSTRATFORDTRATFORD UXBRIDGE EASTEAST HAMHAM BARKINGBARKING Roundabout BBETHNALETHNAL GREENGREEN GGREENFORDREENFORD FFINSBURYINSBURY 6 BBOWOW 9 Great Portland Street Gyratory 12 SSHOREDITCHHOREDITCH WESTWEST HAMHAM 11 HILLINGDON 18 2 10 Hammersmith -

Packet Boat Marina, Packet Boat Lane, Cowley, Uxbridge, Middlesex

- Denham M40 J1 Ickerham A40(T) Packet Boat Marina, Packet Boat Lane, B483 B467 Cowley, Uxbridge, Inset Middlesex, UB8 2JJ Tel: 01895 449851 Pinewood Uxbridge Studio A412 A1 A4007 Marlow Harrow A10 A321 A355 A5 A40 A4020 Slough A4 Hillingdon London A2 M4 Cowley Reading A3 M25 A308 A23 B465 See Inset A437 By Train Iver - Packet Boat Marina is accessible by train.The marina is a 40 minute walk M25 B470 Yiewsley from West Drayton Station. A408 Exit the Station and turn left on Station approach. At the roundabout take the West Drayton first exit onto High Street, then take the 2nd left onto St Stephen's Road. Thorney Pak Iver Golf Course Follow the canal towpath for approximately 0.5 miles until you reach Packet Langley Boat Lane. Turn left on to Packet Boat Lane and walk over the canal bridge. Langley The Marina is on the left. West Drayton By Car - M4 West © - Exit the M4 at junction 4, and at the roundabout take the 1st exit from the J4 C r o west, or 3rd exit from the east on to the A408. Follow the A408 for w n f c r o o approximately 3 miles then turn left on to Packet Boat Lane. Travel over the M4 p m y r i g A3044 Sipson t h M J5 canal bridge and take the immediate left in to the marina. h t e Harmondsworth a 4 n d W d e By Car - M25/M40 a t s a b t A4 a s e - Exit the M25 at junction 16, and merge on to the the M40 East. -

A NEW RECYCLING SERVICE for YIEWSLEY RESIDENTS a Message from Cllr

intouch www.hillingdonconservatives.org If you have a problem or concern call us on 07716 282307 Promoted by Dominic Gilham on behalf of Hillingdon CONTACT DETAILS FOR YOUR Conservatives, both of 36 Harefield Road, Uxbridge, UB8 1PH. Printed by Scubaprint Ltd, Linsford Business Park, YIEWSLEY TEAM TELL US WHAT YOU THINK Linsford Lane, Mytchett, Camberley, GU16 6DJ Let us know if you have any issues of concern: CAN YOU HELP US? Please give us your contact details so we can keep in touch with you about the issues you have raised: I will be supporting Yiewsley Conservatives at the Local Elections Name ■ Ian Edwards Deliver leaflets in my road Address Display a poster at election time ■ Shehryar Wallana Attend social events ■ Peter Davis Join Hillingdon Conservatives Vote by post Telephone: 07716 282307 Home/Mobile No Please return to: Email: Freepost RSTB-LHZG-AYJG [email protected] Email Yiewsley Conservatives Write to us: 36 Harefield Road, Uxbridge, UB8 1PH Freepost RSTB-LHZG-AYJG How we use your information The data you provide will be retained by the Conservative Party and Hayes & Harlington Conservative Association in accordance with the provisions of the Data Yiewsley Conservatives Protection Act 1998 and related legislation. By providing your data to us, you are consenting to the data holders making contact with you in the future by telephone, text or other means, even though you may be registered with the Telephone Preference Service. Your data will not be sold or given to anyone not connected to the Conservative Party. If you do not want the information you give to us to 36 Harefield Road, Uxbridge, be used in this way, or for us to contact you, please indicate by ticking the relevant boxes: Post Email SMS Phone UB8 1PH A NEW RECYCLING SERVICE FOR YIEWSLEY RESIDENTS A message from Cllr. -

Busing Service 2018-19

Busing service 2018-19 From your door to our door Shuttle service ACS Egham operates an extensive busing service for families, Selected buses also offer a shuttle service to pick up and drop off to transport children safely and efficiently between home and school. students at specific points along a designated route: • Door-to-door, Shuttle and London Express Shuttle services Ascot (Zone 1) • Experienced and safe drivers Hampton Hill (Zone 2) • Fees charged to recover costs only. Richmond (Zone 2) We understand the many challenges facing both local and relocating Slough (Zone 2) families and the school Transport Co-ordinator will make every effort Twickenham (Zone 2) to arrange busing for your children from their first day of school. Virginia Water (Zone 1) In order to ensure the process runs smoothly, we would appreciate West Byfleet (Zone 2) your assistance by informing us of your home address as soon as Weybridge (Zone 2) possible. Please note that requests received after 1st August may not be processed in time for the start of the school year. However, rest assured Windsor (Zone 1) that every step will be taken to complete your busing requests with Woking (Zone 2) speed and efficiency. Wokingham (Zone 2) Door-to-Door service London Express Shuttle service Suburban area ACS Egham operates an Express Shuttle servicing Chiswick and All families living within Zones 1 and 2 on the map overleaf can apply Hammersmith. For students living in the West London area, to use our premium Door-to-Door busing service. this provides transportation directly to and from school.