Book Review Josh Bongard* University of Vermont

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Learning Maps for Indoor Mobile Robot Navigation

Learning Maps for Indoor Mobile Robot Navigation Sebastian Thrun Arno BÈucken April 1996 CMU-CS-96-121 School of Computer Science Carnegie Mellon University Pittsburgh, PA 15213 The ®rst author is partly and the second author exclusively af®liated with the Computer Science Department III of the University of Bonn, Germany, where part of this research was carried out. This research is sponsored in part by the National Science Foundation under award IRI-9313367, and by the Wright Laboratory, Aeronautical Systems Center, Air Force Materiel Command, USAF, and the Advanced Research Projects Agency (ARPA) under grant number F33615-93-1-1330. The views and conclusionscontained in this documentare those of the author and should not be interpreted as necessarily representing of®cial policies or endorsements, either expressed or implied, of NSF, Wright Laboratory or the United States Government. Keywords: autonomous robots, exploration, mobile robots, neural networks, occupancy grids, path planning, planning, robot mapping, topological maps Abstract Autonomous robots must be able to learn and maintain models of their environ- ments. Research on mobile robot navigation has produced two major paradigms for mapping indoor environments: grid-based and topological. While grid-based methods produce accurate metric maps, their complexity often prohibits ef®cient planning and problem solving in large-scale indoor environments. Topological maps, on the other hand, can be used much more ef®ciently, yet accurate and consistent topological maps are considerably dif®cult to learn in large-scale envi- ronments. This paper describes an approach that integrates both paradigms: grid-based and topological. Grid-based maps are learned using arti®cial neural networks and Bayesian integration. -

Model Based Systems Engineering Approach to Autonomous Driving

DEGREE PROJECT IN ELECTRICAL ENGINEERING, SECOND CYCLE, 30 CREDITS STOCKHOLM, SWEDEN 2018 Model Based Systems Engineering Approach to Autonomous Driving Application of SysML for trajectory planning of autonomous vehicle SARANGI VEERMANI LEKAMANI KTH ROYAL INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY SCHOOL OF ELECTRICAL ENGINEERING AND COMPUTER SCIENCE Author Sarangi Veeramani Lekamani [email protected] School of Electrical Engineering and Computer Science KTH Royal Institute of Technology Place for Project Sodertalje, Sweden AVL MTC AB Examiner Ingo Sander School of Electrical Engineering and Computer Science KTH Royal Institute of Technology Supervisor George Ungureanu School of Electrical Engineering and Computer Science KTH Royal Institute of Technology Industrial Supervisor Hakan Sahin AVL MTC AB Abstract Model Based Systems Engineering (MBSE) approach aims at implementing various processes of Systems Engineering (SE) through diagrams that provide different perspectives of the same underlying system. This approach provides a basis that helps develop a complex system in a systematic manner. Thus, this thesis aims at deriving a system model through this approach for the purpose of autonomous driving, specifically focusing on developing the subsystem responsible for generating a feasible trajectory for a miniature vehicle, called AutoCar, to enable it to move towards a goal. The report provides a background on MBSE and System Modeling Language (SysML) which is used for modelling the system. With this background, an MBSE framework for AutoCar is derived and the overall system design is explained. This report further explains the concepts involved in autonomous trajectory planning followed by an introduction to Robot Operating System (ROS) and its application for trajectory planning of the system. The report concludes with a detailed analysis on the benefits of using this approach for developing a system. -

The `Icebreaker' Challenge for Social Robotics

The ‘Icebreaker’ Challenge for Social Robotics Weronika Sieińska, Nancie Gunson, Christian Dondrup, and Oliver Lemon∗ (w.sieinska;n.gunson;c.dondrup;o.lemon)@hw.ac.uk School of Mathematical and Computer Sciences, Heriot-Watt University Edinburgh, UK ABSTRACT time where they are sitting in a common waiting room, waiting to Loneliness in the elderly is increasingly becoming an issue in mod- be called for their appointments. While waiting, the vast majority ern society. Moreover, the number of older adults is forecast to of patients sit quietly until their next appointment. We aim to increase over the next decades while the number of working-age deploy a robot to this waiting room that can not only give patients adults will decrease. In order to support the healthcare sector, So- information about their next appointment (thus reducing anxiety) cially Assistive Robots (SARs) will become a necessity. We propose and guide them to it, but which also involves them in more general the multi-party conversational robot ‘icebreaker’ challenge for NLG dialogue using open-domain social chit-chat. The challenge we and HRI that is not only aimed at increasing rapport and acceptance propose is to use non-intrusive general social conversation [6] to of robots amongst older adults but also aims to tackle the issue of involve other people, e.g. another patient sitting next to the patient loneliness by encouraging humans to talk with each other. we are already talking to, in the conversation with the robot. Hence we aim to ‘break the ice’ and get both patients to talk together 1 INTRODUCTION in this multi-party interaction. -

Google's Lab of Wildest Dreams

Google’s Lab of Wildest Dreams By CLAIRE CAIN MILLER and NICK BILTON Published: November 13, 2011 MOUNTAIN VIEW, Calif. — In a top-secret lab in an undisclosed Bay Area location where robots run free, the future is being imagined. It’s a place where your refrigerator could be connected to the Internet, so it could order groceries when they ran low. Your dinner plate could post to a social network what you’re eating. Your robot could go to the office while you stay home in your pajamas. And you could, perhaps, take an elevator to outer space. Ramin Rahimian for The New York These are just a few of the dreams being chased at Times Google X, the clandestine lab where Google is Google is said to be considering the tackling a list of 100 shoot-for-the-stars ideas. In manufacture of its driverless cars in the United States. interviews, a dozen people discussed the list; some work at the lab or elsewhere at Google, and some have been briefed on the project. But none would speak for attribution because Google is so secretive about the effort that many employees do not even know the lab exists. Although most of the ideas on the list are in the conceptual stage, nowhere near reality, two people briefed on the project said one product would be released by the end of the year, although they would not say what it was. “They’re pretty far out in front right now,” said Rodney Brooks, a professor emeritus at M.I.T.’s computer science and artificial intelligence lab and founder of Heartland Robotics. -

Lecture Notes in Artificial Intelligence 1701 Subseries of Lecture Notes in Computer Science Edited by J

Lecture Notes in Artificial Intelligence 1701 Subseries of Lecture Notes in Computer Science Edited by J. G. Carbonell and J. Siekmann Lecture Notes in Computer Science Edited by G. Goos, J. Hartmanis and J. van Leeuwen ¿ Berlin Heidelberg New York Barcelona Hong Kong London Milan Paris Singapore Tokyo Wolfram Burgard Thomas Cristaller Armin B. Cremers (Eds.) KI-99: Advances in Artificial Intelligence 23rd Annual German Conference on Artificial Intelligence Bonn, Germany, September 13-15, 1999 Proceedings ½ ¿ Series Editors Jaime G. Carbonell, Carnegie Mellon University, Pittsburgh, PA, USA Jorg¨ Siekmann, University of Saarland, Saarbrucken,¨ Germany Volume Editors Wolfram Burgard Armin B. Cremers Universitat¨ Bonn, Institut fur¨ Informatik III Romerstraße¨ 164, D-53117 Bonn, Germany E-mail: wolfram/abc @cs.uni-bonn.de { } Thomas Cristaller GMD - Forschungszentrum Informationstechnik GmbH Schloß Birlinghoven, D-53754 Sankt Augustin, Germany E-mail: [email protected] Cataloging-in-Publication data applied for Die Deutsche Bibliothek - CIP-Einheitsaufnahme Advances in artificial intelligence : proceedings / KI-99, 23rd Annual German Conference on Artificial Intelligence, Bonn, Germany, September 13 - 15, 1999. Wolfram Burgard . (ed.). - Berlin ; Heidelberg ; New York ; Barcelona ; Hong Kong ; London ; Milan ; Paris ; Singapore ; Tokyo : Springer, 1999 (Lecture notes in computer science ; Vol. 1701 : Lecture notes in artificial intelligence) ISBN 3-540-66495-5 CR Subject Classification (1998): I.2, I.4, I.5 ISBN 3-540-66495-5 Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg New York This work is subject to copyright. All rights are reserved, whether the whole or part of the material is concerned, specifically the rights of translation, reprinting, re-use of illustrations, recitation, broadcasting, reproduction on microfilms or in any other way, and storage in data banks. -

Staying Ahead in the MOOC-Era by Teaching Innovative AI Courses

Staying Ahead in the MOOC-Era by Teaching Innovative AI Courses Patrick Glauner 1 Abstract be assumed that this competition will intensify even fur- ther in the coming years and decades. In order to justify As a result of the rapidly advancing digital trans- the added value of three to five-year degree programs to formation of teaching, universities have started to prospective students, universities must differentiate them- face major competition from Massive Open On- selves from MOOCs in some way or other. line Courses (MOOCs). Universities thus have to set themselves apart from MOOCs in order to In this paper, we show how we address this challenge at justify the added value of three to five-year de- Deggendorf Institute of Technology (DIT) in our AI courses. gree programs to prospective students. In this DIT is located in rural Bavaria, Germany and has a diverse paper, we show how we address this challenge at student body of different educational and cultural back- Deggendorf Institute of Technology in ML and AI. grounds. Concretely, we present two innovative courses We first share our best practices and present two (that focus on ML and include slightly broader AI topics concrete courses including their unique selling when needed): propositions: Computer Vision and Innovation • Computer Vision (Section3) Management for AI. We then demonstrate how • Innovation Management for AI (Section4) these courses contribute to Deggendorf Institute of Technology’s ability to differentiate itself from In addition to teaching theory, we put emphasis on real- MOOCs (and other universities). world problems, hands-on projects and taking advantage of hardware. -

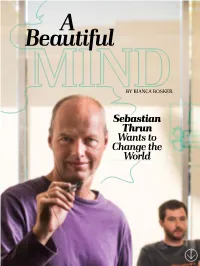

Sebastian Thrun Wants to Change the World Photographs by WINNI WINTERMEYER

A Beautiful BY BIANCA BOSKER Sebastian Thrun Wants to Change the World Photographs by WINNI WINTERMEYER “ Let’s see if I can get us killed,” Sebastian Thrun advises me in a Germanic baritone as we shoot south onto the 101 in his silver Nissan Leaf. Thrun, a pioneer of the self-driving car, cuts across two lanes of tra!c, then jerks into a third, thread- ing the car into a sliver of space between an eighteen- wheeler and a sedan. ¶ Thrun seems determined to halve the normally eleven minute commute from the Palo Alto headquarters of Udacity, the online univer- sity he oversees, to Google X, the secretive Google re- search lab he co-founded and leads. A BEAUTIFUL HUFFINGTON MIND 8.19.12 He’s also keen to demonstrate the urgency of replacing human drivers with the autonomous au- tomobiles he’s engineered. “Would a self-driving car let us do this?” I ask, as mounting G- “ I’ve never seen forces press me back into my seat. a person fail “No,” Thrun answers. “A self- driving car would be much more if they didn’t careful.” Thrun, 45, is tall, tanned, and toned from weekends biking and fear failure.” skiing at his Lake Tahoe home. More surfer than scientist, he smiles frequently and radiates serenity—until he slams on his brakes at the sight of a cop idling When Thrun "nds something he in a speed trap at the side of the wants to do or, better yet, some- highway. Something heavy thumps thing that is “broken,” it drives him against the seat behind us and “nuts” and, he says, he becomes when Thrun opens the trunk mo- “obsessed” with "xing it. -

Curriculum Vitae Prof. Dr. Sebastian Thrun

Curriculum Vitae Prof. Dr. Sebastian Thrun Name: Sebastian Thrun Geboren: 14. Mai 1967 Forschungsschwerpunkte: Robotik, Maschinelles Lernen, Autonomes Fahren Sebastian Thrun ist ein deutscher Informatiker. Er ist einer der Urväter der „Probabilistischen Robotik“, welche statistische Verfahren in der Künstlichen Intelligenz und insbesondere in der Robotik einsetzt. Thrun leitet eine Gruppe von Wissenschaftlern, welche sich im Bereich des Autonomen Fahrens verdient gemacht hat. Akademischer und beruflicher Werdegang 2011 ‐ 2016 Research Professor of Computer Science, Stanford University, USA 2011 ‐ 2014 Google Fellow 2012 Mitgründer der Online‐Akademie Udacity 2007 ‐ 2011 Professor of Computer Science and Electrical Engineering, Stanford University, USA seit 2004 Director des Stanford Artificial Intelligence Laboratory (SAIL) , USA 2003 ‐ 2009 Vice President for Development, NIPS Foundation 2003 ‐ 2007 Associate Professor of Computer Science und (seit 2006) Electrical Engineering, Stanford University, USA 1998 ‐ 2003 Assistant Professor / (seit 2001) Associate Professor of Computer Science, Rrobotics, and Automated Learning and Ddiscovery, Carnegie Mellon University, USA 1995 ‐ 1998 Research Computer Scientist, Carnegie Mellon University, USA 1995 Promotion an der Universität Bonn 1993 Diplom in Informatik und Statistik, Universität Bonn 1988 Vordiplom in Informatik, Wirtschaft und Medizin, Universität Hildesheim Nationale Akademie der Wissenschaften Leopoldina www.leopoldina.org 1 Funktionen in wissenschaftlichen Gesellschaften und Gremien -

A Personal Account on the Development of Stanley, the Robot

AI Magazine Volume 27 Number 4 (2006) (© AAAI) Articles A Personal Account of the Development of Stanley, the Robot That Won the DARPA Grand Challenge Sebastian Thrun ■ This article is my personal account on the work at as Stanley used some state of the art AI methods in Stanford on Stanley, the winning robot in the areas such as probabilistic inference, machine DARPA Grand Challenge. Between July 2004 and learning, and computer vision. Of course, it is also October 2005, my then-postdoc Michael Monte- the story of a step towards a technology that, one merlo and I led a team of students, engineers, and day, might fundamentally change our lives. professionals with the single vision of claiming one of the most prestigious trophies in the field of robotics: the DARPA Grand Challenge (DARPA 2004).1 The Grand Challenge, organized by the Thinking about It U.S. government, was unprecedented in the My story begins in March 2004. Both Michael nation’s history. It was the first time that the U.S. Congress had appropriated a cash price for Montemerlo and I attended the first Grand advancing technological innovation. My team Challenge Qualification Event at the Fontana won this prize, competing with some 194 other Speedway, and Mike stayed on to watch the teams. Stanley was the fastest of five robotic vehi- race. The race was short: within the first seven cles that, on October 8, 2005, successfully navigat- miles, all robotic vehicles had become stuck. ed a 131.6-mile-long course through California’s The best-performing robot, a modified Humvee Mojave Desert. -

KI-99: Advances in Artificial Intelligence (Sample Chapter)

Preface For many years, Artificial Intelligence technology has served in a great variety of successful applications. AI research and researchers have contributed much to the vision of the so-called Information Society. As early as the 1980s, some of us imagined distributed knowledge bases containing the explicable knowledge of a company or any other organization. Today, such systems are becoming reality. In the process, other technologies have had to be developed and AI-technology has blended with them, and companies are now sensitive to this topic. The Internet and WWW have provided the global infrastructure, while at the same time companies have become global in nearly every aspect of enterprise. This process has just started, a little experience has been gained, and therefore it is tempting to reflect and try to forecast, what the next steps may be. This has given us one of the two main topics of the 23rd Annual German Conference on Artificial Intelligence (KI-99) held at the University of Bonn: The Knowledge Society. Two of our invited speakers, Helmut Willke, Bielefeld, and Hans-Peter Kriegel, Munich, dwell on different aspects with different perspectives. Helmut Willke deals with the concept of virtual organizations, while Hans-Peter Kriegel applies data mining concepts to pattern recognition tasks. The three application forums are also part of the Knowledge Society topic: “IT-based innovation for environment and development”, “Knowledge management in enterprises”, and “Knowledge management in village and city planning of the information society”. But what is going on in AI as a science? Good progress has been made in many established subfields such as Knowledge Representation, Learning, Logic, etc. -

Probabilistic Algorithms in Robotics

Probabilistic Algorithms in Robotics Sebastian Thrun April 2000 CMU-CS-00-126 School of Computer Science Carnegie Mellon University Pittsburgh, PA 15213 Abstract This article describes a methodology for programming robots known as probabilistic robotics. The proba- bilistic paradigm pays tribute to the inherent uncertainty in robot perception, relying on explicit represen- tations of uncertainty when determining what to do. This article surveys some of the progress in the field, using in-depth examples to illustrate some of the nuts and bolts of the basic approach. Our central con- jecture is that the probabilistic approach to robotics scales better to complex real-world applications than approaches that ignore a robot’s uncertainty. This research is sponsored by the National Science Foundation (and CAREER grant number IIS-9876136 and regular grant number IIS-9877033), and by DARPA-ATO via TACOM (contract number DAAE07-98-C-L032) and DARPA-ISO via Rome Labs (contract number F30602-98-2-0137), which is gratefully acknowledged. The views and conclusions contained in this document are those of the author and should not be interpreted as necessarily representing official policies or endorsements, either expressed or implied, of the United States Government or any of the sponsoring institutions. Keywords: Artificial intelligence, bayes filters, decision theory, robotics, localization, machine learn- ing, mapping, navigation, particle filters, planning, POMDPs, position estimation 1 Introduction Building autonomous robots has been a central objective of research in artificial intelligence. Over the past decades, researchers in AI have developed a range of methodologies for developing robotic software, ranging from model-based to purely reactive paradigms. -

Finding Structure in Reinforcement Learning

to appear in: Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 7 G. Tesauro, D. Touretzky, and T. Leen, eds., 1995 Finding Structure in Reinforcement Learning Sebastian Thrun Anton Schwartz University of Bonn Dept. of Computer Science Department of Computer Science III Stanford University RÈomerstr. 164, D-53117 Bonn, Germany Stanford, CA 94305 E-mail: [email protected] Email: [email protected] Abstract Reinforcement learning addresses the problem of learning to select actions in order to maximize one's performance in unknown environments. Toscale reinforcement learning to complex real-world tasks, such as typically studied in AI, one must ultimately be able to discover the structure in the world, in order to abstract away the myriad of details and to operate in more tractable problem spaces. This paper presents the SKILLS algorithm. SKILLS discovers skills, which are partially de®ned action policies that arise in the context of multiple, related tasks. Skills collapse whole action sequences into single operators. They are learned by minimizing the com- pactness of action policies, using a description length argument on their representation. Empirical results in simple grid navigation tasks illustrate the successful discovery of structure in reinforcement learning. 1 Introduction Reinforcement learning comprises a family of incremental planning algorithms that construct reactive controllers through real-world experimentation. A key scaling problem of reinforce- ment learning, as is generally the case with unstructured planning algorithms, is that in large real-world domains there might be an enormous number of decisions to be made, and pay-off may be sparse and delayed. Hence, instead of learning all single ®ne-grain actions all at the same time, one could conceivably learn much faster if one abstracted away the myriad of micro-decisions, and focused instead on a small set of important decisions.