John Cunningham, the Consort Music of William Lawes 1602–1645

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

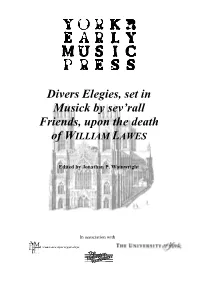

Divers Elegies, Set in Musick by Sev'rall Friends, Upon the Death

Divers Elegies, set in Musick by sev’rall Friends, upon the death of WILLIAM LAWES Edited by Jonathan P. Wainwright In association with Divers Elegies, set in Musick by sev’rall Friends, upon the death of William Lawes Edited by Jonathan P. Wainwright Page Introduction iii Editorial Notes vii Performance Notes viii Acknowledgements xii Elegiac texts on the death of William Lawes 1 ____________________ 1 Cease, O cease, you jolly Shepherds [SS/TT B bc] Henry Lawes 11 A Pastorall Elegie to the memory of my deare Brother William Lawes 2 O doe not now lament and cry [SS/TT B bc] John Wilson 14 An Elegie to the memory of his Friend and Fellow, M r. William Lawes, servant to his Majestie 3 But that, lov’d Friend, we have been taught [SSB bc] John Taylor 17 To the memory of his much respected Friend and Fellow, M r. William Lawes 4 Deare Will is dead [TTB bc] John Cobb 20 An Elegie on the death of his Friend and Fellow-servant, M r. William Lawes 5 Brave Spirit, art thou fled? [SS/TT B bc] Edmond Foster 24 To the memory of his Friend, M r. William Lawes 6 Lament and mourne, he’s dead and gone [SS/TT B bc] Simon Ives 25 An Elegie on the death of his deare fraternall Friend and Fellow, M r. William Lawes, servant to his Majesty 7 Why in this shade of night? [SS/TT B bc] John Jenkins 27 An Elegiack Dialogue on the sad losse of his much esteemed Friend, M r. -

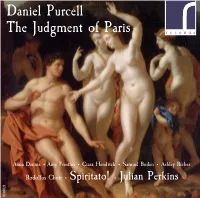

Daniel Purcell the Judgment of Paris

Daniel Purcell The Judgment of Paris Anna Dennis • Amy Freston • Ciara Hendrick • Samuel Boden • Ashley Riches Rodolfus Choir • Spiritato! • Julian Perkins RES10128 Daniel Purcell (c.1664-1717) 1. Symphony [5:40] The Judgment of Paris 2. Mercury: From High Olympus and the Realms Above [4:26] 3. Paris: Symphony for Hoboys to Paris [2:31] 4. Paris: Wherefore dost thou seek [1:26] Venus – Goddess of Love Anna Dennis 5. Mercury: Symphony for Violins (This Radiant fruit behold) [2:12] Amy Freston Pallas – Goddess of War 6. Symphony for Paris [1:46] Ciara Hendricks Juno – Goddess of Marriage Samuel Boden Paris – a shepherd 7. Paris: O Ravishing Delight – Help me Hermes [5:33] Ashley Riches Mercury – Messenger of the Gods 8. Mercury: Symphony for Violins (Fear not Mortal) [2:39] Rodolfus Choir 9. Mercury, Paris & Chorus: Happy thou of Human Race [1:36] Spiritato! 10. Symphony for Juno – Saturnia, Wife of Thundering Jove [2:14] Julian Perkins director 11. Trumpet Sonata for Pallas [2:45] 12. Pallas: This way Mortal, bend thy Eyes [1:49] 13. Venus: Symphony of Fluts for Venus [4:12] 14. Venus, Pallas & Juno: Hither turn thee gentle Swain [1:09] 15. Symphony of all [1:38] 16. Paris: Distracted I turn [1:51] 17. Juno: Symphony for Violins for Juno [1:40] (Let Ambition fire thy Mind) 18. Juno: Let not Toyls of Empire fright [2:17] 19. Chorus: Let Ambition fire thy Mind [0:49] 20. Pallas: Awake, awake! [1:51] 21. Trumpet Flourish – Hark! Hark! The Glorious Voice of War [2:32] 22. -

Jouer Bach À La Harpe Moderne Proposition D’Une Méthode De Transcription De La Musique Pour Luth De Johann Sebastian Bach

JOUER BACH À LA HARPE MODERNE PROPOSITION D’UNE MÉTHODE DE TRANSCRIPTION DE LA MUSIQUE POUR LUTH DE JOHANN SEBASTIAN BACH MARIE CHABBEY MARA GALASSI LETIZIA BELMONDO 2020 https://doi.org/10.26039/XA8B-YJ76. 1. PRÉAMBULE ............................................................................................. 3 2. INTRODUCTION ......................................................................................... 5 3. TRANSCRIRE BACH À LA HARPE MODERNE, UN DÉFI DE TAILLE ................ 9 3.1 TRANSCRIRE OU ARRANGER ? PRÉCISIONS TERMINOLOGIQUES ....................................... 9 3.2 BACH TRANSCRIPTEUR ................................................................................................... 11 3.3 LA TRANSCRIPTION À LA HARPE ; UNE PRATIQUE SÉCULAIRE ......................................... 13 3.4 REPÈRES HISTORIQUES SUR LA TRANSCRIPTION ET LA RÉCEPTION DES ŒUVRES DE BACH AU FIL DES SIÈCLES ....................................................................................................... 15 3.4.1 Différences d’attitudes vis-à-vis de l’original ............................................................. 15 3.4.2 La musique de J.S. Bach à la harpe ............................................................................ 19 3.5 LES HARPES AU TEMPS DE J.S. BACH ............................................................................. 21 3.5.1 Panorama des harpes présentes en Allemagne. ......................................................... 21 4. CHOIX DE LA PIECE EN VUE D’UNE TRANSCRIPTION ............................... -

Rebecca Kellerman Petretta, Soprano Charles Humphries, Counter-Tenor

THE TUESDAY CONCERT SERIES THE CHURCH OF THE EPIPHANY Since Epiphany was founded in 1842, music has played a vital at Metro Center role in the life of the parish. Today, Epiphany has two fine musical instruments which are frequently used in programs and worship. The Steinway D concert grand piano was a gift to the church in 1984, in memory of parishioner and vestry member Paul Shinkman. The 64-rank, 3,467-pipe Æolian- Skinner pipe organ was installed in 1968 and has recently been restored by the Di Gennaro-Hart Co. It was originally given in memory of Adolf Torovsky, Epiphany’s organist and choirmaster for nearly fifty years. HOW YOU CAN HELP SUPPORT THE SERIES 1317 G Street NW Washington, DC 20005 www.epiphanydc.org The Tuesday Concert Series reaches out to the entire [email protected] metropolitan Washington community. Most of today’s free- Tel: 202-347-2635 will offering goes directly to WBC but a small portion helps to defray the cost of administration, advertising, instrument upkeep and the securing of outstanding performers for this concert series. We ask you to consider a minimum of $10. UESDAY ONCERT ERIES However, please do consider being a Sponsor of the Tuesday T C S Concert Series at a giving level that is comfortable for you. 2013 Our series is dependent on your generosity. For more information about supporting or underwriting a complete concert, please contact the Rev. Randolph Charles at 202- 347-2635 ext. 12 or [email protected]. To receive a 15 APRIL 2014 weekly email of the upcoming concert program, email Rev. -

Theatre of Magic Programme Notes

Theatre of Magic PROGRAMME NOTES The English flocked to the theatres when they were reopened after the Restoration. Old plays by Shakespeare, Beaumont, and Fletcher were reworked and eventually supplemented by works by new playwrights. Music, dance, and spectacle were gradually added to complement the drama. The English had not yet embraced opera as it was understood on the Continent, but the amount of music added to the plays became too significant to ignore, and the English writer Roger North invented the term “semi-opera” to describe these entertainments of “half Musick and half Drama.” The leading parts continued to be spoken by actors, while vocal music was allotted to minor characters, whose contributions were essentially diversions, rarely essential to the action. To this was added instrumental music to accompany dance, set the mood, or accompany scene changes. Our concerts this week open with excerpts from two of these semi-operas, both adaptations of Shakespeare’s magical plays, The Tempest and A Midsummer Night’s Dream. Matthew Locke was arguably England’s leading composer at the time of the Restoration in 1660. He became very active in London’s commercial theatres, contributing music for countless plays. He is best known today for the instrumental music he wrote for The Tempest, produced by Thomas Shadwell in 1674. The text of the semi-opera was adapted by Shadwell from an earlier adaptation (1667) of Shakespeare’s original by John Dryden and William Davenant. Shadwell’s version of the play remained popular for some 75 years. Locke’s opening Curtain Tune is particularly striking: it is a musical depiction of the storm that precedes the play, complete with detailed instructions to the performers (including the instruction to play “Violently” at the height of the storm). -

Lully's Psyche (1671) and Locke's Psyche (1675)

LULLY'S PSYCHE (1671) AND LOCKE'S PSYCHE (1675) CONTRASTING NATIONAL APPROACHES TO MUSICAL TRAGEDY IN THE SEVENTEENTH CENTURY ' •• by HELEN LLOY WIESE B.A. (Special) The University of Alberta, 1980 B. Mus., The University of Calgary, 1989 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS • in.. • THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES SCHOOL OF MUSIC We accept this thesis as conforming to the required standard THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA October, 1991 © Helen Hoy Wiese, 1991 In presenting this hesis in partial fulfilment of the requirements for an advanced degree at the University of British Columbia, I agree that the Library shall make it freely available for reference and study. I further agree that permission for extensive copying of this thesis for scholarly purposes may be granted by the head of my department or by his or her representatives. It is understood that copying or publication of this thesis for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. (Signature) Department of Kos'iC The University of British Columbia Vancouver, Canada Date ~7 Ocf I DE-6 (2/68) ABSTRACT The English semi-opera, Psyche (1675), written by Thomas Shadwell, with music by Matthew Locke, was thought at the time of its performance to be a mere copy of Psyche (1671), a French tragedie-ballet by Moli&re, Pierre Corneille, and Philippe Quinault, with music by Jean- Baptiste Lully. This view, accompanied by a certain attitude that the French version was far superior to the English, continued well into the twentieth century. -

Notes – RECORDER CONSORT VIOLS Trotto (Anon Italian 14Th Century) Is a Lively Monophonic Dance in the Form of a Rondeau

- Notes – RECORDER CONSORT VIOLS Trotto (Anon Italian 14th century) is a lively monophonic dance in the form of a rondeau. It originated around 1390.The time signature for the trotto is given as 6/8, Richard Mico (1590-1661) and John Jenkins (1592-1678) are celebrated fantasy and is infused with the triple meter swing, kind of like listening to horse riding and composers. This form is rather like an instrumental madrigal in which several points fox hunting. In Italian, trotto means to trot. of imitation are developed one after the other. Jenkins is our favourite composer, an inexhaustibly inventive melodist and a consummate contrapuntist. Like many of the English fantasy composers and like Haydn, Jenkins resided on the estates of the Virgo Rosa ( Gilles Binchois 1400-1460) provincial gentry; he preferred to be treated as a gentleman house-guest of Lord Gilles Binchois was a Franco-Flemish composer, one of the earliest members of the Dudley North (an amateur treble viol player) rather than an employee. Burgundian School, and one of the three most famous composers of the early 15th century. Binchois is often considered to be the finest melodist of the 15th century, Clive Lane is a Sydney based composer, with published works for viols and writing carefully shaped lines which are easy to sing, and utterly memorable. Most of recorders. He is also an accomplished singer and viol player, and is member of our his music, even his sacred music, is simple and clear in outline. consort. Air is a composition for quartet of viols (treble/tenor/tenor/bass) in a 16 th century style, in which Clive captures the mood of a viol piece by his favourite The words of this sacred motet - composer for viols: John Jenkins. -

Restoration Keyboard Music

Restoration Keyboard Music This series of concerts is based on my researches into 17th century English keyboard music, especially that of Matthew Locke and his Restoration colleagues, Albertus Bryne and John Roberts. Concert 1. "Melothesia restored". The keyboard music by Matthew Locke and his contemporaries. Given at the David Josefowitz Recital Hall, Royal Academy of Music on Tuesday SEP 30, 2003 Music by Matthew Locke (c.1622-77), Frescobaldi (1583-1643), Chambonnières (c.1602-72), William Gregory (fl 1651-87), Orlando Gibbons (1583-1625), Froberger (1616-67), Albert Bryne (c.1621-c.1670) This programmes sets a selection of Matthew Locke’s remarkable keyboard music within the wider context of seventeenth century keyboard playing. Although Locke confessed little admiration for foreign musical practitioners, he is clearly endebted to European influences. The un-measued prelude style which we find in the Prelude of the final C Major suite, for example, suggest a French influence, perhaps through the lutenists who came to London with the return of Charles II. Locke’s rhythmic notation belies the subtle inflections and nuances of what we might call the international style which he first met as a young man visiting the Netherlands with his future regal employer. One of the greatest keyboard players of his day, Froberger, visited London before 1653 and, not surprisingly, we find his powerful personality behind several pieces in Locke’s pioneering publication, Melothesia. As for other worthy composers of music for the harpsichord and organ, we have Locke's own testimony in his written reply to Thomas Salmon in 1672, where, in addition to Froberger, he mentions Frescobaldi and Chambonnières with the Englishmen John Bull, Orlando Gibbons, Albertus Bryne (his contemporary and organist of Westminster Abbey) and Benjamin Rogers. -

Appendix: Catalogue of Restoration Music Manuscripts Bibliography

Musical Creativity in Restoration England REBECCA HERISSONE Appendix: Catalogue of Restoration Music Manuscripts Bibliography Secondary Sources Ashbee, Andrew, ‘The Transmission of Consort Music in Some Seventeenth-Century English Manuscripts’, in Andrew Ashbee and Peter Holman (eds.), John Jenkins and his Time: Studies in English Consort Music (Oxford: Clarendon, 1996), 243–70. Ashbee, Andrew, Robert Thompson and Jonathan Wainwright, The Viola da Gamba Society Index of Manuscripts Containing Consort Music, 2 vols. (Aldershot and Burlington: Ashgate, 2001–8). Bailey, Candace, ‘Keyboard Music in the Hands of Edward Lowe and Richard Goodson I: Oxford, Christ Church Mus. 1176 and Mus. 1177’, Royal Musical Association Research Chronicle, 32 (1999), 119–35. ‘New York Public Library Drexel MS 5611: English Keyboard Music of the Early Restoration’, Fontes artis musicae, 47 (2000), 51–67. Seventeenth-Century British Keyboard Sources, Detroit Studies in Music Bibliography, 83 (Warren: Harmonie Park Press, 2003). ‘William Ellis and the Transmission of Continental Keyboard Music in Restoration England’, Journal of Musicological Research, 20 (2001), 211–42. Banks, Chris, ‘British Library Ms. Mus. 1: A Recently Discovered Manuscript of Keyboard Music by Henry Purcell and Giovanni Battista Draghi’, Brio, 32 (1995), 87–93. Baruch, James Charles, ‘Seventeenth-Century English Vocal Music as reflected in British Library Additional Manuscript 11608’, unpublished PhD dissertation, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill (1979). Beechey, Gwilym, ‘A New Source of Seventeenth-Century Keyboard Music’, Music & Letters, 50 (1969), 278–89. Bellingham, Bruce, ‘The Musical Circle of Anthony Wood in Oxford during the Commonwealth and Restoration’, Journal of the Viola da Gamba Society of America, 19 (1982), 6–71. -

Emma Kirkby Soprano Anthony Rooley Lute

THE UNIVERSITY MUSICAL SOCIETY OF THE UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN Emma Kirkby Soprano Anthony Rooley Lute THURSDAY EVENING, NOVEMBER 4, 1982, AT 8:30 RACKHAM AUDITORIUM, ANN ARBOR, MICHIGAN The English Orpheus A Contention between Hope and Despair ...................... JOHN DOWLAND Fantasia ............................................. ALFONSO FERRABOSCO Grief, keep within ........................................... JOHN DANYEL Pavan ....................................................... FERRABOSCO Thou Mighty God .............................................. DOWLAND Semper Dowland, semper dolens ................................. DOWLAND Sweet birds deprive us never ................................ JOHN BARTLETT INTERMISSION Come, shepherds come \ Perfect and endless circles are! ............................... WILLIAM LAWES Love I obey J I rise and grieve } The Lark J ..................................... HENRY LAWES A tale out of Anacreon j Stript of their green \ What a sad fate J .......................... HENRY PURCELL When first Amintas sued for a kiss) Mr. Rooley: London, Decca, Hyperion, and L'Oiseau Lyre Records. Miss Kirkby: Decca and Hyperion Records. Twelfth Concert of the 104th Season Special Concert About the Artists Anthony Rooley studied for three years at the Royal Academy of Music where his love of history and philosophy led him to study the music of the Renaissance. He owned his first lute in 1968 and later combined it with voice and viol to form The Consort of Musicke, one of today's leading specialist Renaissance ensembles. The ensemble covers all the major secular music of the period 1450-1650, with special emphasis in recent years on the English repertoire circa 1600. One major project to emanate from the Consort is a 21-record set of the "Complete Works of John Dowland," which has received accolades from critics throughout the world. In addition to the Consort, which is nearly a full-time concern, Mr. -

Download Booklet

2 CD John Jenkins as the occasion required; he was apparently JOHN JENKINS (1592-1678) Four Part Consort Music never officially attached to any household, for COMPLETE FOUR-PART CONSORT MUSIC his pupil Roger North wrote: “I never heard that Amateur viol players throughout the world love he articled with any gentleman where he playing the consort music of John Jenkins, resided, but accepted what they gave him.” probably more than any other English composer of the great golden era of music for multiple We can guess that they must have been quite viols, that ranges from William Cornyshe in advanced players in that much of the music CD1 CD2 1520 through to Henry Purcell in 1680. And was highly virtuosic in the division style, where 1 Fantasia No. 1 [3.24] 1 Fantasia No. 10 [3.58] the reason why is not hard to fathom: a rare slow-moving lines are decorated by ‘dividing’ the 2 Fantasia No. 2 [3.57] 2 Fantasia No. 11 [3.30] melodic gift is married to an exceptionally deep longer notes into ever shorter ones. However, the 3 Fantasia No. 3 [4.03] 3 Fantasia No. 12 [4.18] understanding of harmony and modulation; consort style was mostly concerned with more effortless counterpoint gives each part an melodic, mellifluous lines and Jenkins wrote a 4 Fantasia No. 4 [3.39] 4 Fantasia No. 13 [3.16] equal voice in the musical conversation; and large body of such music for four, five and six viols. 5 5 Pavan in D Minor [6.09] Fantasia No. -

Spring 2021 PROGRAM #: EMN 20-42 RELEASE

Early Music Now with Sara Schneider Broadcast Schedule — Spring 2021 PROGRAM #: EMN 20-42 RELEASE: April 5, 2021 Joyful Eastertide! This week's show presents an eclectic array of music to celebrate Easter, including motets by François Couperin, Jacob Obrecht, Antoine Busnois, and Orlando Gibbons. We'll also hear from two composers based in Hamburg: Matthias Weckmann and Thomas Selle. Our performers include Weser Renaissance Bremen, Capilla Flamenca, Cantus Cölln, and Henry's Eight. PROGRAM #: EMN 20-43 RELEASE: April 12, 2021 Treasures from Dendermonde The music of Hildegard of Bingen has come down to us in only two sources, one of which is known as the Dendermonde Codex, named after the abbey in the Belgian town where it is now housed. We'll hear Psallentes, a Belgian ensemble specializing in chant, performing selections from this codex. We'll also hear them singing 14th and 15th century chant from Tongeren. PROGRAM #: EMN 20-44 RELEASE: April 19, 2021 Recent Releases We're sampling a couple of exciting recent releases this week! The Mad Lover features sonatas, suites, grounds, and various bizzarie from 17th century England performed by Théotime Langlois de Swarte (violin) and Thomas Dunford (lute). We'll also hear from Ensemble Morgaine, with tracks from their 2021 release Evening Song, which focuses on 16th century hymns, songs, and Psalms from the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. PROGRAM #: EMN 20-45 RELEASE: April 26, 2021 Petrucci and the Odhecaton Ottaviano Petrucci was a printer working in Venice at the turn of the 16th century. He revolutionized the distribution of music and cultivated a taste for the Franco-Flemish style in Italy with the publication of Harmonice Musices Odhecaton in 1501.