Full Report Title in Title Case

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Jamie's $ Foods Carol and James Robertson Box 38 Milo, AB.T0L1L0

_ o / Ad Rates Subscription Rates Business Directory $ 5.00 . Milo $ 16.00 Quarter Page 6.00 (- pickup,delivery or mailed) Half Page 8.00 Mailed (outside Milo) 24.00 Full Pages 15.00 Single Copies 2.00 Classifieds 2.00 Please note that those who paid for a Milo subscription by mail ($24) on our previous rates have payed $8 too much. Your subscription The followinq items are free of charae renewal date will be extended by 6 months. Notices Please sign them, no letters will be Announcements printed if not signed. ( Wedding, Anniversary, Births, Showers, etc.) Requests to remain anonymous Cards of Thanks will not be honoured. News items Articles Please send items to the followinq volunteer staff Layout Editors - Barb Godkin - 599 -2213, 485-8389 Carol Robertson Production - Colleen Deitz 599-2306 Betty A Subscriptions -Iris Gough - ............................. 599 - 2377 Notices - Julie Nelson - ................................. .... 599-2175 Charlotte Nelson - .......................... 59 9 -2 2 5 3 Cartoons & “Kids Say” - Marina Vannatta -... ..... 381 -6389 Milo Can Opener Box 12, Milo, Alberta, TOL 1L0 Please note the new fax Fax# 599 - 2457 number! (fax shares line with phone so you will get the answering machine sometimes. You can also fax to Milo Municipal Library at 599-3850) Email: [email protected] Items may be left at Jamie’s Foods in the Can Opener box at back of store or at Milo Municipal Library. Please Note: The deadline for articles that need typing, etc. to be submitted is the Monday before the last Friday of each month. If your article is ready for press, we can accept it until Wednesday. -

The High Costs of For-Pro T Health Services in Alberta

$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$ $$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$ $$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$ $$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$ $$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$ $$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$ $$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$ $$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$ $$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$ $$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$ $$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$ $$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$ DELIVERY MATTERS The High Costs of For-Prot Health Services in Alberta $$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$ $$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$ $$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$ $$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$ $$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$ $$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$ $$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$ $$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$ $$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$ $$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$ $$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$ $$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$ A PARKLAND REPORT | APRIL 2012 delivery matters: t h e h i g h c o s t s o f fo r - p ro f i t h e a l t h s e r v i c e s i n a l b e r t a Published by the Parkland Institute April, 2012 contents a b o u t t h e a u t h o r 3 acknowledgements 3 a b o u t t h e p a r k l a n d i n s t i t u t e 4 introduction 5 c o n t e x t 6 1. h rc c a s e s t u d y – a d e e p e r l o o k 6 a s p e c i a l relationship : h rc a n d a l b e r t a h e a l t h s e r v i c e s ( a h s ) 7 h rc e x p a n d s a n d g o e s b a n k r u p t 10 t h e g o ve r n m e n t i n t e r ve n e s 10 2. t h e a l b e r t a h i p a n d k n e e replacement p ro j e c t 11 3. -

Calgary - Upper NW Health Data and Summary

Alberta Health Primary Health Care - Community Profiles Community Profile: Calgary - Upper NW Health Data and Summary Primary Health Care Division February 2013 Alberta Health, Primary Health Care Division February 2013 Community Profile: Calgary - Upper NW Table of Contents Introduction .................................................................................................................................................. i Community Profile Summary .............................................................................................................. iii Zone Level Information .......................................................................................................................... 1 Map of Alberta Health Services Calgary Zone ......................................................................................... 2 Population Health Indicators ..................................................................................................................... 3 Table 1.1 Zone versus Alberta Population Covered as at March 31, 2012 ........................................... 3 Table 1.2 Health Status Indicators for Zone versus Alberta Residents, 2010 and 2011 (BMI, Physical Activity, Smoking, Self-Perceived Mental Health) ............................................................................................... 3 Table 1.3 Zone versus Alberta Infant Mortality Rates (per 1,000 live births), Fiscal Years 2008/2009 to 2010/2011 .................................................................................. -

Asthma Care in the Calgary Zone

COMMENTARY The Community Pediatric Asthma Service—Together We’re Better: Asthma care in the Calgary zone Ambris Ford, BHSc, RRT, CRE, Cinde Little, RRT, CRE, CTE, Cindy Bronconnier RRT, CRE, CTE, Kathy Courtney, RRT, CRE, CTE, Val Olson, RRT, CRE, CTE, Shirley van de Wetering, BSc MBA, Mary Noseworthy, MD FRCPC, Brenda Dueck, Terri Humphries, Debbie Desrosiers A Ford, C Little, C Bronconnier, K Courtney, V Olson, S van de Wetering, M Noseworthy, B Dueck, T Humphries, D Desrosiers. The Community Pediatric Asthma Service—Together we’re better: Asthma care in the Calgary zone. Can J Respir Ther 2018;54(4):1–6. doi: 10.29390/cjrt-2018-015. INTRODUCTION Every HIF required independent evaluation. One of the key find- The Community Pediatric Asthma Service in Calgary, Alberta, ings of the Final Evaluation Report was the reduction in emergency and focuses on improving asthma self-management skills for patients and hospital utilization: “There was a 65.1% reduction in emergency visits families through one-on-one education sessions in the Calgary Zone. and a 61.9% reduction in hospital days over an 18-month period We also aim to increase physician confidence to diagnose and manage among the first 112 patients seen by the iCAN educator” [9]. The asthma by sharing medically accurate, consistent information in inno- Belfield Evaluation formed the basis for a business case that resulted vative ways. in permanent funding for a community focused asthma education ser- The Public Health Agency of Canada estimates the national preva- vice in June 2005, which is today’s Community Pediatric Asthma lence of asthma to be 15.3% for the 1–19-year-old age group [1] and, Service. -

ALBERTA FOOTHILLS INVESTMENT && BUSINESS Site Selection Guide

ALBERTA FOOTHILLS INVESTMENT && BUSINESS Site Selection Guide Town of Black Diamond • M.D. of Foothills • Town of High River • Town of Okotoks • Town of Turner Valley • A Business Development Initiative of the Alberta Foothills Region www.albertafoothills.ca Welcome to the Foothills Region In the quiet of the dawn of new days, the first light paints itself across the snowpack clinging to the face of the Rocky Table of Contents Mountains to the west. The green grasses bend away from the breeze, Welcome 2 over a washboard of rolling hills as far as the The Foothills Region 3-5 eye can see. Our at a Glance common geography - the Foothills Region of The Calgary Region 6-7 Southern Alberta - is inspired and inspiring. Investment Targets 8-11 From artist to entrepreneur to movie The Foothills Region: industry to new resident drawn by its beauty, a Industry Profile 12 vibrant, growing and prosperous economy Business 13 has emerged. The Resources bounds of opportunity live on imagination’s Real Estate 14 terms. Finance 15 Today, 65,000 people live in our five Tourism 16-17 communities - the M.D. Infrastructure of Foothills #31 and the towns of Okotoks, High River, Turner Valley and Black M.D. of Foothills 18-20 Diamond. Population growth exceeds the Alberta average. Investment opportunity abounds. Town of Okotoks 21-24 The Foothills Region has come together to embolden pursuit of Town of 25-27 opportunity sympathetic to the physical endurance of a High River geography that counts among the world’s special places. Our common goal is to promote responsible, innovative, Town of 28-30 prosperous, and sustainable development of our region. -

View Report, the Calgary Health Region Began Several New Initiatives Designed to Improve Performance in the Region’S Emergency and Urgent Care Services

TABLE OF CONTENTS FOREWORD........................................................................................................................................................................................3 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY .................................................................................................................................................................4 BACKGROUND..................................................................................................................................................................................5 PURPOSE.............................................................................................................................................................................................6 APPROACH.........................................................................................................................................................................................7 Identification of Calgary Health Region Processes and Practices................................................................................................8 Identification of Leading Processes and Practices.........................................................................................................................9 FINDINGS AND RECOMMENDATIONS ....................................................................................................................................10 Patient Perspective.........................................................................................................................................................................10 -

The Department of Medicine and the Calgary Health Region Invite

Respirologist – Clinical Epidemiology Department of Medicine, University of Calgary – Alberta Health Services The Department of Medicine, University of Calgary and Alberta Health Services (AHS), Calgary Zone, invite applications for a position as a clinician researcher in the Division of Respiratory Medicine as a Clinical Assistant or Clinical Associate Professor, based on qualifications and experience. A candidate with a proven research track record as an independent investigator will be considered for appointment at a Clinical Associate Professor level. The successful candidate should have research experience in health economics, administrative databases, and/or clinical epidemiology. They must have a proven record of excellence in research as demonstrated by scholarly publications; and the ability to compete successfully for peer-review funding. Consideration will also be given to candidates with a research track record in sleep or exercise physiology. Preference will be given to candidates with an MSc, and interest in graduate student supervision. This position provides 50% protected time for research. Qualifications include an MD, FRCPC Respirology, and eligibility for licensure in the Province of Alberta. It is expected that the incumbent will be appointed to a major clinical Faculty position within the Division of Respiratory Medicine, Department of Medicine at the University of Calgary. The candidate will be based at the Rockyview General Hospital, Calgary, Alberta and will participate in respirology call coverage, rounds, and local clinical programs. Our clinical focus is in COPD management, specialized pulmonary diagnostics, and cardiopulmonary exercise testing/pulmonary rehabilitation. Our area of academic interest is in epidemiology and health services research, with many members holding cross-appointments in the Department of Community Health Sciences. -

Information and Privacy Commissioner of Alberta

INFORMATION AND PRIVACY COMMISSIONER OF ALBERTA Investigation Report Concerning Collection and Use of Health Information and the Destruction of Personal Information Investigation Report H2011-IR-001 & F2011-IR-001 May 25, 2011 Alberta Health Services (Investigations H3184 and F5360) Introduction [1] On November 24, 2009, the Information and Privacy Commissioner (the “Commissioner”) received a complaint from an individual (the “Complainant”) alleging that his health information had been collected and used by employees of the former Calgary Health Region (CHR), now Alberta Health Services (AHS), in contravention of the Health Information Act (HIA). [2] The Complainant was admitted to the Foothills Medical Centre (FMC) in January 2006 pursuant to an admission certificate under the Mental Health Act (MHA). The Complainant states that his father was contacted by a nurse from the FMC without his permission and against his wishes on the day on which he was admitted to the hospital. He also states that a physician at the FMC obtained his consent to collect limited information about him from his father, his friend and his general practitioner (GP) on the second day of his stay in the hospital, but that the information collected went beyond the scope of the consent he provided. The Complainant raised the issue that video recordings that could have substantiated complaints about his care were destroyed after 30 days. The Complainant was also involuntarily admitted to the Peter Lougheed Centre (PLC) in March 2006 under the MHA after going there to “get a second opinion”. He states that staff at the PLC obtained and used his records from the FMC without his consent while he was a patient at the PLC. -

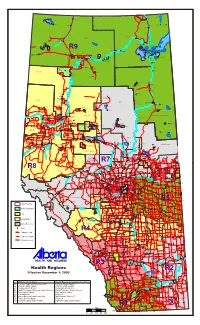

R9 R7 R8 R3 R1 R2 R4 R5 R6

Charles Lake I.R. 225 Fitzgerald Indian Cabins Jackfish Point I.R. 214 Bistcho Lake Cornwall Lake Collin Lake I.R. 213 I.R. 224 I.R. 223 Steen River Hay Camp I.D. 24 M.D. 23 Peace Point Upper Hay River Meander River I.R. 212 Carlson Landing Amber River I.R. 211 Sand Point Sweet Grass Landing I.R. 221 Habay Devil’s Gate I.R. 220 Zama Lake Allison Bay Hay Lake I.R. 210 I.R. 219 I.R. 209 R9 Dog Head I.R. 218 Fort Chipewyan Chateh Chipewyan I.R. 201A Garden Creek Quatre Fourches Little Fishery Chipewyan I.R. 201B Fifth Meridian Jean D’Or Prairie Child Lake Beaver Ranch High Level I.R. 215 Chipewyan Rainbow Lake I.R. 164A Rocky Lane I.R. 163B I.R. 201 Boyer Beaver Ranch Chipewyan I.R. 201C I.R. 163A Fox Lake Jackfish I.R. 164 Fox Lake Old Fort Chipewyan I.R. 201D Beaver Ranch I.R. 162 I.R. 217 Chipewyan I.R. 201E Bushe River North Vermilion Settlement I.R. 163 I.R. 207 Fort Vermilion Little Red River I.R. 173B Fort Vermilion Vermilion Chutes Embarras La Crete Buffalo Head Prairie Tall Cree Chipewyan I.R. 173A I.R. 201F Paddle Prairie Metis Settlement Chipewyan Paddle Prairie I.R. 201G M.D. 22 Tall Cree I.R. 173 Carcajou I.R. 187 Keg River Carcajou Wadlin Lake I.R. 173C Namur River I.R. 174A Bitumount Namur River I.R. 174B Fort MacKay Fort McKay I.R. 174 Hotchkiss Mildred Lake Notikewin Chipewyan Lake Manning M.D. -

Black Diamond Health Data and Summary

Alberta Health Primary, Community and Indigenous Health Community Profile: Black Diamond Health Data and Summary 3rd edition , March 2017 Alberta Health, Primary, Community and Indigenous Health & Analytics and Performance Reporting March 2017 Community Profile: Black Diamond Table of Contents Introduction .................................................................................................................................................. i Community Profile Summary .............................................................................................................. iii Zone Level Information .......................................................................................................................... 1 Map of Alberta Health Services South Zone ............................................................................................ 2 Population Health Indicators ..................................................................................................................... 3 Table 1.1 Zone versus Alberta Population Covered as at March 31, 2016 ............................................ 3 Table 1.2 Health Status Indicators for Zone versus Alberta Residents, 2013 and 2014 (Body Mass Index, Physical Activity, Smoking, Self-Perceived Mental Health) ............................................................................... 3 Table 1.3 Zone versus Alberta Infant Mortality Rates (per 1,000 live births), Years 2013 – 2015 ................................................................................................................ -

Foothills Medical Centre Alberta Children's Hospital

Regional Trauma Service Annual Report April 1, 2003 to March 31, 2004 Regional Trauma Services 2003/2004 Calgary Health Region Annual Regional Trauma Services Report 2003/2004 Table of Contents Organization Structure.....................................................................................................................................ii Vision, Mission, Values, Roles ........................................................................................................................iii Introduction ......................................................................................................................................................iv Executive Summary.........................................................................................................................................2 Regional Trauma Services Activities ...............................................................................................................11 Alberta Children’s Hospital Paediatric Trauma Report....................................................................................21 Trauma Statistics & Outcome Data .................................................................................................................25 Trauma Statistics: Peter Lougheed Centre & Rockyview General Hospital...................................................44 Performance Indicators: Foothills Medical Centre..........................................................................................48 Performance Indicators: Alberta -

Background to Health Technology Assessment

Putting HTA into Practice MODULE 1v3 BACKGROUND TO HEALTH TECHNOLOGY ASSESSMENT Revised: August 2012 Surgery Strategic Clinical Network: Evidence Decision Support Program MODULE 1v3 – Putting HTA into Practice WELCOME Welcome to “Module 1v3: Background to Health Technology Assessment,” which is the first part of an educational series entitled “Putting HTA into Practice.” This module is an up-dated version of a previously developed education module (1) in 2005, which was one of a six-part series on Health Technology Assessment (HTA). The original 2005 Health Technology Assessment Modules were prepared for the Department of Surgery by Elizabeth Oddone Paolucci, PhD, Medical Education & Research Unit, Educational Consultant; Tyrone Donnon, PhD, Medical Education & Research Unit, Assistant Professor, Faculty of Medicine; Paule Poulin, PhD, Associate Director, Office of Surgical Research, Calgary Health Region. (1), with funding provided by the Canadian Coordinating Office for Health Technology Assessment (CCOHTA) now known as the Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health (CADTH). The purpose of this revision is to provide a background to HTA and the HTA framework in Alberta for those undergoing workshops on “Putting HTA into Practice” — a training program for putting HTA Into Practice available for Clinical Networks and other Operation Leaders within Alberta Health Services. This module describes HTA terminology, the principles and purpose of HTA, examples of HTA producers and users, the HTA framework in Alberta, and some of the limitations and challenges when integrating HTA into practice. Your feedback and comments on both the module and training workshops will be greatly appreciated! Please send comments to [email protected].