Green Island Cement (Holdings) Ltd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2015 Annual Report

Ports and Related Services Retail Infrastructure Energy Telecommunications 2015 Annual Report 22nd Floor, Hutchison House, 10 Harcourt Hutchison House, Hong Kong Road, 22nd Floor, Telephone: +852 2128 1188 Facsimile: www.ckh.com.hk +852 2128 1705 Corporate Information CK Hutchison Holdings Limited Board of dIreCtors eXeCUtIVe dIreCtors NoN-eXeCUtIVe dIreCtors Chairman CHOW Kun Chee, Roland, LLM LI Ka-shing, GBM, KBE, LLD (Hon), DSSc (Hon) LEE Yeh Kwong, Charles, GBM, GBS, OBE, JP Commandeur de la Légion d’Honneur Grand Officer of the Order Vasco Nunez de Balboa LEUNG Siu Hon, BA (Law) (Hons), Hon LL.D. Commandeur de l’Ordre de Léopold George Colin MAGNUS, OBE, BBS, MA Group Co-Managing director and INdepeNdeNt NoN-eXeCUtIVe dIreCtors Deputy Chairman KWOK Tun-li, Stanley, BSc (Arch), AA Dipl, LLD (Hon), ARIBA, MRAIC LI Tzar Kuoi, Victor, BSc, MSc, LLD (Hon) CHENG Hoi Chuen, Vincent, GBS, OBE, JP Group Co-Managing director The Hon Sir Michael David KADOORIE, GBS, LLD (Hon), DSc (Hon) FOK Kin Ning, Canning, BA, DFM, FCA (ANZ) Commandeur de la Légion d’Honneur Commandeur de l’Ordre des Arts et des Lettres Commandeur de l’Ordre de la Couronne CHOW WOO Mo Fong, Susan, BSc Commandeur de l’Ordre de Leopold II Group Deputy Managing Director LEE Wai Mun, Rose, JP, BBA Frank John SIXT, MA, LLL Group Finance Director and Deputy Managing Director William Elkin MOCATTA, FCA Alternate to Michael David Kadoorie IP Tak Chuen, Edmond, BA, MSc Deputy Managing Director William SHURNIAK, SOM, LLD (Hon) KAM Hing Lam, BSc, MBA WONG Chung Hin, CBE, JP Deputy -

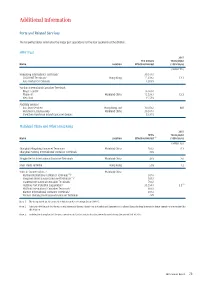

Additional Information

additional Information ports and related services The following tables summarise the major port operations for the four segments of the division. HpH trust 2015 The Group’s Throughput Name Location Effective Interest (100% basis) (million TEU) Hongkong International Terminals/ 30.07% / COSCO-HIT Terminals/ Hong Kong 15.03% / 12.1 Asia Container Terminals 12.03% Yantian International Container Terminals - Phase I and II/ 16.96% / Phase III/ Mainland China 15.53% / 12.2 West Port 15.53% Ancillary Services - Asia Port Services/ Hong Kong and 30.07% / N/A Hutchison Logistics (HK)/ Mainland China 30.07% / Shenzhen Hutchison Inland Container Depots 23.35% Mainland China and other Hong Kong 2015 HPH’s Throughput Name Location Effective Interest (1) (100% basis) (million TEU) Shanghai Mingdong Container Terminals/ Mainland China 50% / 8.3 Shanghai Pudong International Container Terminals 30% Ningbo Beilun International Container Terminals Mainland China 49% 2.0 River Trade Terminal Hong Kong 50% 1.2 Ports in Southern China - Mainland China (2) Nanhai International Container Terminals / 50% / (2) Jiangmen International Container Terminals / 50% / Shantou International Container Terminals/ 70% / (3) Huizhou Port Industrial Corporation/ 33.59% / 2.5 Huizhou International Container Terminals/ 80% / Xiamen International Container Terminals/ 49% / Xiamen Haicang International Container Terminals 49% Note 1: The Group holds an 80% interest in Hutchison Ports Holdings Group (“HPH”). Note 2: Although HPH Trust holds the economic interest in the two River Ports in Nanhai and Jiangmen in Southern China, the legal interests in these operations are retained by this division. Note 3: Includes the throughput of the port operations in Gaolan and Jiuzhou that were disposed during the second half of 2015. -

The Competitive Strategy of an Ethnic Chinese Corporate Group Under the Hong Kong Economic Development, with Special Emphasis on the Cheung Kong Group

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Ritsumeikan Research Repository © Institute of lnternational Relations and Area Studies, Ritsumeikan University The Competitive Strategy of an Ethnic Chinese Corporate Group under the Hong Kong Economic Development — With Special Emphasis on the Cheung Kong Group — Mori, Masaki* Abstract This paper discusses about the competitive strategy of an ethnic Chinese corporate group under the Hong Kong economic development, with special emphasis on the Cheung Kong group. First, Hong Kong economy, its industrial development and the economic relationship between Hong Kong and the mainland China is historically examined. Second, the growth strategy of a Hong Kong corporate group, the Cheung Kong group, is discussed how to diversify its business in adapting to Hong Kong economic environment. Third, the characteristics of its corporate governance and accounting management are discussed as a family-owned corporate group. Keywords: Competitive Strategy, Ethnic Chinese Corporate Group, the Hong Kong Economic Development, the Cheung Kong Group Ritsumeikan International Affairs Vol.12, pp.21–38 (2014). * Associate Professor, College of Business Administration, Ritsumeikan University, Japan. E-mail: [email protected] 22 Ritsumeikan International Affairs 【Vol. 12 1. Introduction This paper examines the Competitive Strategy of an ethnic Chinese corporate group under the Hong Kong economic development, through a case study of the Cheung Kong Group. The focus herein is on corporate governance and accounting management within family enterprises. You Zhongxun (1998) proposes that “The reason for the economic prosperity of ethnic Chinese…is largely attributable to Asia’s economic development. -

Hutchison Whampoa Limited

Hutchison Whampoa Limited Hutchison House, 22nd Floor 10 Harcourt Road, Hong Kong Telephone: (852) 2128 1188 Facsimile: (852) 2128 1705 www.hutchison-whampoa.com Hutchison Whampoa Limited Whampoa Hutchison ANNUAL REPORT 2000 REPORT ANNUAL Ports and Related Services Telecommunications and e-commerce Property and Hotels Retail and Manufacturing Energy, Infrastructure, Finance and Investments ANNUAL REPORT 2000 Hutchison Whampoa Limited Hutchison House, 22nd Floor 10 Harcourt Road, Hong Kong Telephone: (852) 2128 1188 Facsimile: (852) 2128 1705 www.hutchison-whampoa.com Hutchison Whampoa Limited Whampoa Hutchison ANNUAL REPORT 2000 REPORT ANNUAL Ports and Related Services Telecommunications and e-commerce Property and Hotels Retail and Manufacturing Energy, Infrastructure, Finance and Investments ANNUAL REPORT 2000 Business Highlights The Group’s hotels generally reported improved occupancy as the number of international Husky Energy, renamed after travellers has steadily the merger of Husky Oil with increased with the recovering Renaissance Energy, is listed on The Group formed a strategic economies in Asia. the Toronto Stock Exchange. alliance with NTT DoCoMo and KPN Mobile whereby the two The Group formed a joint companies have a 20% and venture with CSFBdirect named 15% interest in Hutchison 3G Hutchison CSFBdirect to provide UK respectively. online securities services. HPH expanded its Asian port interests by acquiring an aggregate 31.5% interest in Kelang Multi Terminal in Malaysia, and also a 47.9% The Group established stake in Koja Terminal in BigboXX.com, an online Jakarta, Indonesia. office supplies and procurement operation. Hutchison Telecommunications (Australia) successfully bid for 1800 MHz licences covering five major cities in Australia which will be used to provide 3G network services. -

Solid Foundation Fosters Long-Term Development

20 1 7 Annual Report Solid Foundation Fosters Long-term Development 22nd Floor, Hutchison House, 10 Harcourt Road, Hong Kong Telephone: +852 2128 1188 2017 Annual Report Facsimile: +852 2128 1705 www.ckh.com.hk WorldReginfo - 7a0610cc-4251-4d12-8195-61d40b71508e Corporate Information CK Hutchison Holdings Limited BOARD OF DIRECTORS EXECUTIVE DIRECTORS NON-EXECUTIVE DIRECTORS Chairman CHOW Kun Chee, Roland, LLM LI Ka-shing, GBM, KBE, LLD (Hon), DSSc (Hon) CHOW WOO Mo Fong, Susan, BSc Commandeur de la Légion d’Honneur Grand Officer of the Order Vasco Nunez de Balboa LEE Yeh Kwong, Charles, GBM, GBS, OBE, JP Commandeur de l’Ordre de Léopold LEUNG Siu Hon, BA (Law) (Hons), LL.D. (Hon) Group Co-Managing Director and George Colin MAGNUS, OBE, BBS, MA Deputy Chairman LI Tzar Kuoi, Victor, BSc, MSc, LLD (Hon) INDEPENDENT NON-EXECUTIVE DIRECTORS Group Co-Managing Director KWOK Tun-li, Stanley, BSc (Arch), AA Dipl, LLD (Hon), ARIBA, MRAIC FOK Kin Ning, Canning, BA, DFM, FCA (ANZ) CHENG Hoi Chuen, Vincent, GBS, OBE, JP Frank John SIXT, MA, LLL The Hon Sir Michael David KADOORIE, GBS, LLD (Hon), DSc (Hon) Group Finance Director and Deputy Managing Director Commandeur de la Légion d’Honneur Commandeur de l’Ordre des Arts et des Lettres IP Tak Chuen, Edmond, BA, MSc Commandeur de l’Ordre de la Couronne Deputy Managing Director Commandeur de l’Ordre de Leopold II (William Elkin MOCATTA, FCA as his alternate) KAM Hing Lam, BSc, MBA Deputy Managing Director LEE Wai Mun, Rose, JP, BBA LAI Kai Ming, Dominic, BSc, MBA William SHURNIAK, S.O.M., M.S.M., LLD -

Subsidiary and Associated Companies and Jointly Controlled Entities at 31 December 2002

Hutchison Whampoa Limited Annual Report 2002 135 Principal Subsidiary and Associated Companies and Jointly Controlled Entities at 31 December 2002 Place of incorporation / Nominal value of Percentage Subsidiary and principal issued ordinary of equity associated companies and place of share capital / attributable jointly controlled entities operations registered capital to the Group Principal activities Ports and related services Buenos Aires Container Terminal Argentina ARS 10,000,000 100 Container terminal operating Services S.A. ✡ COSCO-HIT Terminals (Hong Kong) Hong Kong HK$ 40 43 Container terminal operating Limited Ensenada International Terminal, Mexico MXP 160,195,000 100 Container terminal operating S.A. de C.V. Europe Container Terminals B.V. Netherlands Euro 45,378,021 76 Container terminal operating Freeport Container Port Limited Bahamas B$ 2,000 95 Container terminal operating Harwich International Port Limited United Kingdom GBP 16,812,002 90 Container terminal operating Hongkong International Terminals Limited Hong Kong HK$ 20 87 Holding company & container terminal operating ✡ The Hongkong Salvage and Towage Hong Kong HK$ 20,000,000 50 Tug fleet operating Company, Limited ✡ Hongkong United Dockyards Limited Hong Kong HK$ 76,000,000 50 Ship repairing & general engineering Hutchison Delta Ports Limited Cayman US$ 2 100 Holding company Islands / Hong Kong Hutchison Port Holdings Limited British Virgin US$ 1 100 Holding company Islands / Hong Kong Hutchison Korea Terminals Limited South Korea Won 4,107,500,000 100 Container terminal operating Hutchison Ports (UK) Finance Plc United Kingdom GBP 50,000 90 Finance Hutchison Westports Limited United Kingdom GBP 50,000,000 90 Holding company Internacional de Contenedores Mexico MXP 138,623,200 100 Container terminal operating Asociados de Veracruz, S.A. -

Board and Senior Management

SEVEN-YEAR MANAGEMENT BOARD AND CHAIRMAN’S LETTER REPORT OF FINANCIAL SUMMARY DISCUSSION AND ANALYSIS SENIOR MANAGEMENT THE DIRECTORS Board and Senior Management KAM Hing Lam aged 56, has been the Group Managing Director of the Company since its incorporation in May 1996. He has also been the Deputy Managing Director of Cheung Kong (Holdings) Limited since February 1993. He is also the President and Chief Executive Officer of CK Life Sciences Int’l., (Holdings) Inc., an executive director of Hutchison Whampoa Limited and Hongkong Electric Holdings Limited. He holds a Bachelor of Science degree in Engineering and a Master’s degree in Business Administration. George Colin MAGNUS Victor Li, H.L. Kam (from left to right) aged 67, has been Deputy Chairman of the Company since its incorporation in May 1996. He has also been an executive director of Cheung Kong (Holdings) Limited Directors’ Biographical Information since 1980 and Deputy Chairman of Cheung Kong (Holdings) Limited since 1985. He is also the Chairman of LI Tzar Kuoi, Victor Hongkong Electric Holdings Limited and an executive aged 38, has been the Chairman of the Company since director of Hutchison Whampoa Limited. He holds a its incorporation in May 1996. He is also the Chairman of Master’s degree in Economics. CK Life Sciences Int’l., (Holdings) Inc., the Managing Director and Deputy Chairman of Cheung Kong (Holdings) Limited, Deputy Chairman of Hutchison Whampoa Limited, an executive director of Hongkong Electric Holdings Limited, the Co-Chairman of Husky Energy Inc. and a director of The Hongkong and Shanghai Banking Corporation Limited. -

Additional Information

Additional Information Ports and Related Services The following tables summarise the port operations for the four segments of the division. HPH Trust 2017 The Group’s Throughput Name Location Effective Interest (100% basis) (million TEU) Hongkong International Terminals/ 30.07% / COSCO-HIT Terminals/ Hong Kong 15.03% / 11.7 Asia Container Terminals 12.03% Yantian International Container Terminals - Phase I and II/ 16.96% / Phase III/ Mainland China 15.53% / 12.7 West Port 15.53% Huizhou International Container Terminals Mainland China 12.42% 0.2 Ancillary Services - Asia Port Services/ Hong Kong and 30.07% / N/A Hutchison Logistics (HK)/ Mainland China 30.07% / Shenzhen Hutchison Inland Container Depots 23.35% Mainland China and Other Hong Kong 2017 Hutchison Ports’ Throughput Name Location Effective Interest (1) (100% basis) (million TEU) Shanghai Mingdong Container Terminals/ Mainland China 50% / 9.3 Shanghai Pudong International Container Terminals 30% Ningbo Beilun International Container Terminals Mainland China 49% 2.1 River Trade Terminal Hong Kong 50% 1.0 Ports in Southern China - (2) Nanhai International Container Terminals / 50% / (2) Jiangmen International Container Terminals / 50% / Shantou International Container Terminals/ Mainland China 70% / Huizhou Port Industrial Corporation/ 33.59% / 2.0 Xiamen International Container Terminals/ 49% / Xiamen Haicang International Container Terminals 49% Note 1: The Group holds an 80% interest in Hutchison Ports Holdings Group (“Hutchison Ports”). Note 2: Although HPH Trust holds the -

Global Infrastructure Player Annual Report 2017

CK INFRASTRUCTURE HOLDINGS LIMITED Annual Report 2017 Stock Code: 1038 GLOBAL INFRASTRUCTURE PLAYER ANNUAL REPORT 2017 ANNUAL REPORT CK INFRASTRUCTURE HOLDINGS LIMITED 12th Floor, Cheung Kong Center, 2 Queen’s Road Central, Hong Kong Tel: (852) 2122 3133 Fax: (852) 2501 4550 www.cki.com.hk CKI A Leading Player in the Global Infrastructure Arena CKI is a global infrastructure company that aims to make the world a better place through a variety of infrastructure investments and developments in different parts of the world. The Group has diversified investments in Energy Infrastructure, Transportation Infrastructure, Water Infrastructure, Waste Management, Waste-to-energy, Household Infrastructure and Infrastructure Related Businesses. Its investments and operations span Hong Kong, Mainland China, the United Kingdom, Continental Europe, Australia, New Zealand and North America. CONTENTS 008 Ten-year Financial Summary 010 Chairman’s Letter 016 Group Managing Director’s Report 021 Long Term Development Strategy 022 Awards 026 Business Review 028 Investment in Power Assets 030 Infrastructure Investments in United Kingdom 036 Infrastructure Investments in Australia 044 Infrastructure Investments in New Zealand 046 Infrastructure Investments in Continental Europe 049 Infrastructure Investments in Canada 052 Infrastructure Investments in Mainland China 054 Investments in Infrastructure Related Businesses 056 Financial Review 058 Board and Key Personnel 073 Report of the Directors 088 Independent Auditor’s Report 094 Consolidated Income Statement -

Awardee List 2018-19 獲嘉許僱主名單2018-19

Awardee List 2018-19 獲嘉許僱主名單 2018-19 MPF Excellent Employer 卓越積金好僱主 「電子供款獎」 「積金推廣獎」 e-Contribution Award MPF Support Award 安達臣瀝青有限公司 Anderson Asphalt Limited 嘉靈科技亞太有限公司 Carling Technologies Asia-Pacific Ltd 中原集團管理有限公司 Centaline Group Management Limited China Cement Company (International) 中國水泥(國際)有限公司 Limited 青洲英坭(集團)有限公司 Green Island Cement (Holdings) Limited 青洲英坭有限公司 Green Island Cement Company Limited 青洲國際有限公司 Green Island International (BVI) Limited 青洲船務代理有限公司 Green Island Shipping Agency Limited Molex Hong Kong/China Limited Schenker International (H.K.) Ltd. 全球國際貨運有限公司 Page | 1 Good MPF Employer 5 Years 積金好僱主 5 年 「電子供款獎」 「積金推廣獎」 e-Contribution Award MPF Support Award 303 科技有限公司 303 Technology Limited 科文實業有限公司 4M Industrial Development Limited 八端國際有限公司 8D International Limited ACCO Asia Limited 精英製模有限公司 Ace Mold Company Limited 安輝機械工程有限公司 Aegis Engineering Co., Ltd. 國際機場協會 Airports Council International Alpha Start Limited AmMed Cancer Center (Central) Limited 近利(香港)有限公司 Antalis (Hong Kong) Limited Anway Limited 康瑋有限公司 Arrium Mining Services Asia Limited 亞洲貨櫃碼頭有限公司 Asia Container Terminals Limited 智邁企業有限公司 Atico International Ltd Australia and New Zealand Banking Group 澳新銀行集團有限公司 Limited Page | 2 Good MPF Employer 5 Years 積金好僱主 5 年 「電子供款獎」 「積金推廣獎」 e-Contribution Award MPF Support Award 銀聯信託有限公司 Bank Consortium Trust Company Limited Bank of Communications Co., Ltd. Hong 交通銀行股份有限公司香港分行 Kong Branch 香港暢道科技有限公司 Barrier Free Access (HK) Limited Bauer Equipment Hong Kong Limited Baynard Limited 銀聯金融有限公司 BCT Financial Limited 德豪財務顧問有限公司 -

Results for the Year Ended 31 December 2019 Highlights

Hong Kong Exchanges and Clearing Limited and The Stock Exchange of Hong Kong Limited take no responsibility for the contents of this document, make no representation as to its accuracy or completeness and expressly disclaim any liability whatsoever for any loss howsoever arising from or in reliance upon the whole or any part of the contents of this document. RESULTS FOR THE YEAR ENDED 31 DECEMBER 2019 HIGHLIGHTS Post-IFRS 16(1) Basis Local Reported 2019 2018 currencies currency HK$ million HK$ million change change Total Revenue (2) 439,856 453,230 +1% -3% Total EBITDA (2) 136,049 113,580 +24% +20% Total EBIT (2) 75,344 72,885 +7% +3% Profit attributable to ordinary shareholders 39,830 39,000 +6% +2% Earnings per share (3) HK$10.33 HK$10.11 +2% Final dividend per share HK$2.30 HK$2.30 — Full year dividend per share HK$3.17 HK$3.17 — Pre-IFRS 16(1) Basis Local Reported 2019 2018 currencies currency HK$ million HK$ million change change Total Revenue (2) 439,856 453,230 +1% -3% Total EBITDA (2) 112,068 113,580 +2% -1% Total EBIT (2) 71,108 72,885 +1% -2% Profit attributable to ordinary shareholders 39,888 39,000 +6% +2% (1) As Hong Kong Financial Reporting Standards are fully converged with International Financial Reporting Standards in the accounting for leases, for ease of reference, International Financial Reporting Standard 16 “Leases” (“IFRS 16”) and the precedent lease accounting standard International Accounting Standard 17 “Leases” (“IAS 17”) are referred to in this results announcement interchangeably with Hong Kong Financial Reporting Standard 16 “Leases” (“HKFRS 16”) and Hong Kong Accounting Standard 17 “Leases” (“HKAS 17”), respectively. -

Hutchison Whampoa Limited

Hutchison Whampoa Limited annual report 2003 annual report shaping the future 2003 Hutchison Whampoa Limited Hutchison House, 22nd Floor, 10 Harcourt Road, Hong Kong Telephone : (852) 2128 1188 Facsimile : (852) 2128 1705 www.hutchison-whampoa.com Corporate Information Shaping the future Chairman Company Secretary Just as technology makes life easier, so it makes LI Ka-shing, KBE, GBM, LLD, DSSc Edith SHIH, MA, EdM businesses at Hutchison Whampoa Limited more Deputy Chairman Auditors efficient and effective. The wide ranging LI Tzar Kuoi, Victor, BSc, MSc PricewaterhouseCoopers applications of technology give management the Group Managing Director Bankers time and flexibility to devise strategies that shape FOK Kin-ning, Canning, BA, DFM, ACA (Aus) The Hongkong and Shanghai the Group’s future by clicking on solutions that Banking Corporation Limited Standard Chartered Bank raise productivity of the Group’s 170,000 Executive Directors J P Morgan Chase CHOW WOO Mo Fong, Susan, BSc employees and by offering greater convenience Deputy Group Managing Director Frank John SIXT, MA, LLL Share Registrars and higher quality service to the Group’s Group Finance Director Computershare Hong Kong Investor Services Limited customers across the globe, every day. LAI Kai Ming, Dominic, BSc, MBA Rooms 1712-1716, 17th Floor George Colin MAGNUS, OBE, MA Hopewell Centre KAM Hing Lam, BSc, MBA 183 Queen’s Road East Hong Kong With the aid of technology, the success story of Directors HWL continued in 2003 on all business fronts. The Hon Michael David KADOORIE, GBS, Registered Office The Group is committed to continue forging Chevalier de la Légion d’Honneur, Hutchison House, 22nd Floor Commandeur de l’Ordre de Leopold II 10 Harcourt Road, Hong Kong ahead on the highway of prosperity to the benefit Simon MURRAY, CBE Telephone : (852) 2128 1188 OR Ching Fai, Raymond Facsimile : (852) 2128 1705 of shareholders, customers, business partners William SHURNIAK, LLD + Peter Alan Lee VINE, OBE, LLD, VRD, JP + and employees everywhere in the world.