B824: Turner—A Study in Persistence and Change Louis A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

State of Maine

MAINE STATE LEGISLATURE The following document is provided by the LAW AND LEGISLATIVE DIGITAL LIBRARY at the Maine State Law and Legislative Reference Library http://legislature.maine.gov/lawlib Reproduced from scanned originals with text recognition applied (searchable text may contain some errors and/or omissions) • a " , Ii DOCUMENTS I'lllNTED BY ORDl!R 01' THE LEGISLATUR!r~ OF THE STA'rE OF MAINE, " DURING ITS SBSSIONS A. D. 1 8 5 1-- 2-. att!Jttt;ta: WILLIAM T. JOHNSON, PRINTER TO THE STATE. I 852. LIS T OF STOCKHOLDERS, (With the amonnt of Stock held by each Jan. 1, 1851,) IN THE BANKS OF MAINE. Prepared and published agreeably to a Resolve of the Legislature, approved March 21, 1839 ; By JOHN G. SAWYER. Secretary of State. ~u1lusta: WILLIAM T. JOHNSON, PRINTER TO THE STATE. 1 851 . STATE OF MAINE. Resolve requzrzng the Secretary of State to publislt a List of the Stockholders of the Banks in this State. RESOLVED, That the Secretary of State be and hereby is required annually to publish a List of the Stockholders in each Bank in this State, with the amount of Stock owned by each Stockholder agreeably to the returns made by law to the Legislature of this State; and it shall be the duty of the Secretary of State to distribute to each town in this State, and also to each Bank in this State one copy of such printed list; and it shall be the duty of the Secretary of State to require any Bank, which may neglect to make the returns required by law to the Legislature, to furnish him forthwith with a List of the Stockholders of such Bank, and also the amount of Stock owned by each Stockholder. -

EXTENSIONS of REMARKS July 16, 1991 EXTENSIONS of REMARKS LET's EASE the SUFFERING of in Iraq

18548 EXTENSIONS OF REMARKS July 16, 1991 EXTENSIONS OF REMARKS LET'S EASE THE SUFFERING OF in Iraq. As a result, Saddam is free to per Emaciated pets now prowl Baghdad alleys, THE PEOPLE OF IRAQ secute his own people just as he persecuted set loose by owners who can no longer afford the people of Kuwait. to feed them. International aid has thus far HON. WM. S. BROOMREID We may not be able to remove Saddam, but staved off the apocalyptic rates of disease we can certainly ensure that his people, and and malnutrition feared a few months ago, OF MICHIGAN but conditions remain ripe for an epidemic. not he and his cronies, are in a position to IN THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES On a back street of Saddam City, the Mosan benefit from the country's financial assets and family spent a recent day bailing raw sewage Tuesday, July 16, 1991 its great wealth of natural resources. from the front room of their mud brick Mr. BROOMFIELD. Mr. Speaker, yester In the recent war in the gulf, America's great home. With Iraq's water system crippled by day's Wall Street Journal brought a fresh re scientific minds and military strategists were bomb damage and lack of spare parts, pipes minder of the pain and suffering being en able to wage a war of terrific ferocity but lim often burst, flooding streets with fetid green dured by the people of Iraq. ited scope. Many Iraqi civilians died, but I'd sludge. The Mosans' three-room hovel, home to 13 In the words of the Journal's reporter, Tony like to think that many more survived because America was intent on aiming its precision people, has no furniture and only one appli Horwitz, who is in Saddam City, "Iraq's econ ance: a creaking refrigerator cooling crusts omy is in a free fall, and so are most of its weapons against Saddam and his military and of bread and chunks of fat, the poor Iraqi's people. -

The Granite Monthly, a New Hampshire Magazine, Devoted to Literature, History, and State Progress. Vol. 37

/ T 4 s DURHAM Library Association* Book -r-t=x-^f-^. Volume —-?rf^ Source Received Cost Accession No- . »*v>V THE GRANITE MONTHLY A New Hampshire Magazine DEVOTED TO HISTORY, BIOGRAPHY, LITERATURE, AND STATE PROGRESS VOLUME XXXVll CONCORD, N. H. PUBLISHED BY THE GRANITE MONTHLY COMPANY 1904 N V.37 Published, 1904 By the Granite Monthly Company Concord, N. H. Printed and Illustrated by the Rumford Printing Company (Rum/ord Press) Concord, AVtc Hn>n.fishire, U. S. A. The Granite Monthly. CONTENTS OF VOLUME XXXVIl. yiily—December, igo^. Ayres, Philip W., Thk Poorest Situation in New Hampshire and How to Change It ......... 65 Baynes, Ernest Harold, George I. Putnam .... 49 Beede, Eva J., Midsu.mmer {poem) ...... 87 Blake, Amos J., Sketch of the Life and Character of Col. Amos A. Parker 104 Boody, Louis Milton, The Front Fence ..... 43 Brown, Gilbert Patten, John Stark, the Hero of Bennington 73 Buflfum, Jesse H.. Dempsey's Trick ...... 68 Carr, Laura Garland, A Fact {poem) . 72 Chesley, Charles Henry, On the Tide {poetn) .... 17 Clough, William O., Crayon Portrait of Abraham Lincoln . lOI Colby, H. B., A Glass of Ale ....... 3 Charles C. Hayes ........ 15 Dempsey's Trick, Jesse H. BuiTum ...... 68 Editorial Notes : An Automobile Law ....... 88 Road Improvements under State Supervision . 89 Some Lessons from the Berlin, N. H., Fire . 133 Road Improvement in So.me of Our Smaller Towns 134 Fact, A {poem) , Laura Garland Carr ...... 72 Farr, Ellen Burpee, Our "Old Home Week"' {poem) 57 Forest Situation in New Hampshire, The, and I low to Change W. Ayres ......... -

Stalin Revolutionary in an Era of War 1St Edition Pdf, Epub, Ebook

STALIN REVOLUTIONARY IN AN ERA OF WAR 1ST EDITION PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Kevin McDermott | 9780333711224 | | | | | Stalin Revolutionary in an Era of War 1st edition PDF Book It was under this name that he went to Switzerland in the winter of , where he met with Lenin and collaborated on a theoretical work, Marxism and the National and Colonial Question. They argue that in the article On the Slogan for a United States of Europe the expression "triumph of socialism [ Seller Rating:. Vladimir Lenin died in January and by the end of that year in the second edition of the book Stalin's position started to turn around as he claimed that "the proletariat can and must build the socialist society in one country". Modern History Review. Refresh and try again. Tucker's subject, however, which isn't Mont I have admired Robert Tucker's work for decades now, and I am glad at long last to take up the first of his two volume study of Stalin. Brazil United Kingdom United States. Retrieved August 27, Egan The major difficulty is a lack of agreement about what should constitute Stalinism. Stalin and Lenin were close friends, judging from this photograph. He wrote that the concept of Stalinism was developed after by Western intellectuals so as to be able to keep alive the communist ideal. Retrieved September 20, Palgrave Macmillan UK. Antonio rated it it was amazing Jun 04, Retrieved 7 October During the quarter of a century preceding his death, the Soviet dictator Joseph Stalin probably exercised greater political power than any other figure in history. -

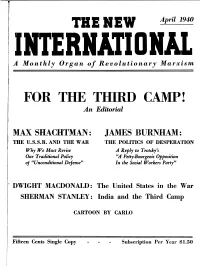

FOR the THIRD CAMP! an Editorial

TBElfEW April 1940 A Monthly Organ of Revolutionary Marxism FOR THE THIRD CAMP! An Editorial MAX SHACHTMAN: JAMES BURNHAM: THE U.S.S.R. AND THE WAR THE POLITICS OF DESPERATION Why We Must Re"ise A Reply to Trotsky's Our Traditional Policy t:~ Petty-Bourgeois Opposition oj t:t:Unconditional Defense" In the Social Workers Party" ( DWIGHT MACDONALD: The United States in the War SHERMAN STANLEY: India and the Third Camp CARTOON BY CARLO Fifteen Cents Single Copy Subscription Per Year $1.50 The Voice of the Third Camp Must Be Heard! Statement by the Editors THE CONVENTION of the Socialist Workers Party, held at as the organized movement of the Fourth International in this the end of several months of internal discussion, has just been con~ country, the Opposition constitutes a clear majority of the total eluded in New York. A majority of the delegates elected to the membership. convention voted for the resolutions on the Russian and organiza Under these conditions, to continue to remain silent inside the tional questions presented by the Majority faction, and which can ranks of the party would be unforgivable in a revolutionist. Under be read in the post-convention issue of the Socialist Appeal. these conditions, to place confidence in the democratic guarantees How deep-going and vigorous was the discussion in the S.W.P. offered by the official party leadership which has given the minority may be judged by the fact that it has brought the party to the no cause to place confidence in it during the course of the internal brink of a split, the danger of which is by no means dispelled. -

Bio-Bibliographical Sketch of Max Shachtman

The Lubitz' TrotskyanaNet Max Shachtman Bio-Bibliographical Sketch Contents: • Basic biographical data • Biographical sketch • Selective bibliography • Notes on archives Basic biographical data Name: Max Shachtman Other names (by-names, pseud. etc.): Cousin John * Marty Dworkin * M.S. * Max Marsh * Max * Michaels * Pedro * S. * Max Schachtman * Sh * Maks Shakhtman * S-n * Tr * Trent * M.N. Trent Date and place of birth: September 10, 1904, Warsaw (Russia [Poland]) Date and place of death: November 4, 1972, Floral Park, NY (USA) Nationality: Russian, American Occupations, careers, etc.: Editor, writer, party leader Time of activity in Trotskyist movement: 1928 - ca. 1948 Biographical sketch Max Shachtman was a renowned writer, editor, polemicist and agitator who, together with James P. Cannon and Martin Abern, in 1928/29 founded the Trotskyist movement in the United States and for some 12 years func tioned as one of its main leaders and chief theoreticians. He was a close collaborator of Leon Trotsky and translated some of his major works. Nicknamed Trotsky's commissar for foreign affairs, he held key positions in the leading bodies of Trotsky's international movement before, in 1940, he split from the Socialist Workers Party (SWP), founded the Workers Party (WP) and in 1948 definitively dissociated from the Fourth International. Shachtman's name was closely webbed with the theory of bureaucratic collectivism and with what was described as Third Campism ('Neither Washington nor Moscow'). His thought had some lasting influence on a consider able number of contemporaneous intellectuals, writers, and socialist youth, both American and abroad. Once a key figure in the history and struggles of the American and international Trotskyist movement, Shachtman, from the late 1940s to his death in 1972, made a remarkable journey from the left margin of American society to the right, thus having been an inspirer of both Anti-Stalinist Marxists and of neo-conservative hard-liners. -

Helen Schiff Papers

Helen Schiff Collection Papers, 1940-1967 .5 linear feet 1 manuscript box Accession #1172 OCLC # The papers of Helen Schiff were placed in the Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs in 1970 by Helen Schiff and were opened for research in May of 1984. In 1940 the Socialist Workers Party split into majority and minority factions over the Hitler-Stalin Pact. The majority faction followed Leon Trotsky's unconditional defense of the Soviet Union's policies; the minority condemned the Hitler-Stalin Pact as an unjustifiable alliance. These differences led the minority faction to leave the Party and to form the Workers Party. In 1957 young members of the Socialist Workers Party joined with left-wing members of the independent Young Socialist League, who were in opposition to their organization's proposed merger with the Socialist Party-Social Democratic Federation, and members of the Labor Youth League, youth section of the Communist Party-USA, to form the Young Socialist Supporters and to publish Young Socialist. In April 1960 the Supporters held a convention and reorganized themselves into the Young Socialist Alliance, youth section of the Socialist Workers Party. In 1965 Young Socialists (Canada) was founded as the youth section of the League for Socialist Action, a fraternal organization of the SWP. The Helen Schiff Collection consists of materials documenting the 1940 split in the Socialist Workers Party and the founding of the Young Socialist Alliance and the Young Socialists (Canada) in the early 1960's. In addition, it contains miscellaneous reports, bulletins, and newsletters of the Socialist Workers Party and the Fourth International. -

A Place We Now Call “Home” the New Raider Athletic Field

CENTRAL CATHOLIC HIGH SCHOOL | FALL 2014 Emblem–––––––––––––––––– a publication for alumni, students, parents & friends –––––––––––––––––– A PLACE WE NOW CALL “Home” The New Raider Athletic Field MEMORABLE HIGHLIGHTS Graduation 2014 CROWD APPEAL Brad Damphousse ’00 Our 2014 SHINING STARS 2014 Annual Report of PHILANTHROPY EmblemCENTRAL CATHOLIC HIGH SCHOOL Accredited by the New England Association of Schools & Colleges. Central Catholic High School is an independent, Catholic co-educational college preparatory secondary school in Lawrence, Massachusetts. It has been under the direction of the Marist Brothers since its founding in 1935. Central Catholic admits academically qualified students without regard to race, color, orientation, ethnic origin or faith tradition. PRESIDENT PRINCIPAL Inside this Issue Br. Richard Carey, FMS Doreen A. Keller BOARD OF DIRECTORS PROVINCIAL SUPERIOR Br. Benjamin Consigli, FMS Commencement: Class of 2014 2 EXECUTIVE COMMITTEE/OFFICERS Every Moment, Every Day – Always Together Michael T. Torrisi ’92, Chairman Gary J. Gallant ’75, Past Chairman Joseph P. Faro ’87, Vice Chairman Shining Stars 2014 4 Terence F. Sanz, Secretary-Clerk Margaret G. Ward, Treasurer 8 Alumni Spotlight: Atty. Laurence J. Rossi ’64, Executive Committee, Member-at-Large Jeffrey D. Sheehy, Executive Committee, Member-at-Large Brad M. Damphousse '00 – All About Crowd Appeal MEMBERS-AT-LARGE Matthew W. Fitzgerald ’02 Br. James McKnight, FMS Measuring Excellence – The A.P. Studies Program 11 Gerald Kent, Jr. Peter J. Rayno ’78 Steven A. Lindsay Ann Regan 12 Alumni Joseph Malarney Br. Sean Sammon, FMS Patrick B. Maraghy ’64 Michael J. Tangney ’63 16 Thank You – Giving Br. Joseph Matthews, FMS James B. Zenevitch ’80 Raider “Field of Dreams” Becomes a Reality The Emblem is a publication of the Office of Institutional Advancement. -

The Historical and International Foundations of the Socialist Equality Party

The Historical and International Foundations of the Socialist Equality Party Adopted by the SEP Founding Congress August 3-9, 2008 © 2008 Socialist Equality Party Contents The Principled Foundations of the Socialist Equality Party ......................................................................................................................1 The Origins and Development of Marxism .................................................................................................................................................2 The Origins of Bolshevism ..........................................................................................................................................................................3 The Theory of Permanent Revolution ........................................................................................................................................................4 Lenin’s Defense of Materialism ...................................................................................................................................................................5 Imperialist War and the Collapse of the Second International ..................................................................................................................6 The Russian Revolution and the Vindication of Permanent Revolution ..................................................................................................8 The Communist International ..................................................................................................................................................................10 -

A New Look at the Invasion of Eastern Maine, 1814

Maine History Volume 15 Number 1 Article 2 7-1-1875 A New Look at the Invasion of Eastern Maine, 1814 Barry J. Lohnes University of Maine Augusta Ronald Banks University of Maine Orono Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/mainehistoryjournal Part of the Military History Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Lohnes, Barry J., and Ronald Banks. "A New Look at the Invasion of Eastern Maine, 1814." Maine History 15, 1 (1975): 4-29. https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/mainehistoryjournal/vol15/iss1/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UMaine. It has been accepted for inclusion in Maine History by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UMaine. For more information, please contact [email protected]. British - s&w Winter Route --------Between St. John And CanadianFront Northern Bound - Anticost QUEBEC CITY ONTREAL HALIFAX PLATTs LIVERPOOL Vt. Bath 'PORTLAND YARMOUTl SHELBURNE BIDDEFORD KITTERY r PORTSMOUTH SALEM Mass. BOSTON FALMOUTH The Theater & Nantucket Is OF operations NEW YORK A NEW LOOK AT THE INVASION OF EASTERN MAINE, 1814 By Barry J. Lohnes During the last year of the War of 1812 the British launched an invasion of the Maine District of Massachusetts, capturing a large salient between the Penobscot River and the New Brunswick border. Few historians have appraised adequately the inability of the national and state governments to defend the region of eastern New England, nor have they researched carefully the British motivations behind the assault. Only through a closer look at the defensive errors of the Americans is it possible to realize that the British victory, though a tactical success, was a strategic failure. -

Genealogical Dictionary of Maine and New Hampshire, Vol. 2

^7<y,/ kSLct f>1>ï /933 To the binder: these 2 leaves, pp.vil-x are throw-outs in the final binding: GENEALOGICAL DICTIONARY of MAINE and NEW HAMPSHIRE PART II THE SOUTHWORTH PRESS PORTLAND, MAINE 1933 PREFACE TO PART II Although over four years have passed, the promise made in the Preface to Part I, that before Part II should go to press, all of my materials would have been thoroughly worked over for the whole book, is ixnkept. Not only have my minutes from so many years among the records not been fidly uti lized, but people who have studied certain families will often find that au thentic matter in print has escaped notice. Genealogists trained to library work will turn to many such omissions. Yet I do, to console myself, hold to the belief that James Savage himself, had he -in our day- thought of writing his Genealogical Dictionary, would have abandoned it almost before start ing. As it was, he exhausted every printed book from cover to cover (often led into errors thereby). Today such books have multiplied more than a hundred fold. In the interim between Parts I and II, books have gotten into print which fill me with dismay, and worse— books -flung- into print, reckless of errors; and some of these by a genealogist of high reputation. Is there not now enough of such material on the library shelves without increasing it 1 More to the point, shall I add to it? Personally I have reached a conviction that we have arrived at a stage where the desideratum is not the multiplication of genealogical books, nor even the extension of research, but the rescuing of genealogy itself from being brought into public contempt by reckless graspers after high ancestry and their exploiters. -

Albert Glotzer Papers

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/tf1t1n989d No online items Register of the Albert Glotzer papers Finding aid prepared by Dale Reed Hoover Institution Library and Archives © 2010 434 Galvez Mall Stanford University Stanford, CA 94305-6003 [email protected] URL: http://www.hoover.org/library-and-archives Register of the Albert Glotzer 91006 1 papers Title: Albert Glotzer papers Date (inclusive): 1919-1994 Collection Number: 91006 Contributing Institution: Hoover Institution Library and Archives Language of Material: English Physical Description: 67 manuscript boxes, 6 envelopes(27.7 Linear Feet) Abstract: Correspondence, writings, minutes, internal bulletins and other internal party documents, legal documents, and printed matter, relating to Leon Trotsky, the development of American Trotskyism from 1928 until the split in the Socialist Workers Party in 1940, the development of the Workers Party and its successor, the Independent Socialist League, from that time until its merger with the Socialist Party in 1958, Trotskyism abroad, the Dewey Commission hearings of 1937, legal efforts of the Independent Socialist League to secure its removal from the Attorney General's list of subversive organizations, and the political development of the Socialist Party and its successor, Social Democrats, U.S.A., after 1958. Creator: Glotzer, Albert, 1908-1999 Hoover Institution Library & Archives Access The collection is open for research; materials must be requested at least two business days in advance of intended use. Publication Rights For copyright status, please contact the Hoover Institution Library & Archives. Acquisition Information Acquired by the Hoover Institution Library & Archives in 1991. Preferred Citation [Identification of item], Albert Glotzer papers, [Box no., Folder no.