Emerging Issues in Sustainable Development International Trade Law and Policy Relating to Natural Resources, Energy, and the Environment

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

WEAI Program 2010-FINAL.Pub

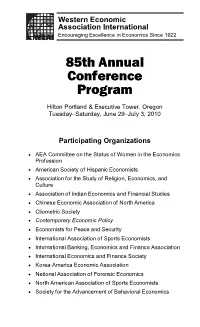

Western Economic Association International Encouraging Excellence in Economics Since 1922 85th Annual Conference Program Hilton Portland & Executive Tower, Oregon Tuesday–Saturday, June 29–July 3, 2010 Participating Organizations • AEA Committee on the Status of Women in the Economics Profession • American Society of Hispanic Economists • Association for the Study of Religion, Economics, and Culture • Association of Indian Economics and Financial Studies • Chinese Economic Association of North America • Cliometric Society • Contemporary Economic Policy • Economists for Peace and Security • International Association of Sports Economists • International Banking, Economics and Finance Association • International Economics and Finance Society • Korea-America Economic Association • National Association of Forensic Economics • North American Association of Sports Economists • Society for the Advancement of Behavioral Economics START OR RENEW YOUR MEMBERSHIP TODAY! Western Economic Association International membership offers all of these great benefits... • Individual subscriptions to both • Reduced submission fee for your quarterly journals, Economic Inquiry individual paper submitted for and Contemporary Economic Policy presentation at either conference if (includes full collection online). you choose not to organize a • Reduced registration fees for the session. Annual Conference and for the • Manuscript submission fee is Biennial Pacific Rim Conference. waived for submitting your • Opportunity to organize your own conference paper to EI or CEP if sessions for both conferences with you do so within six months after the submission fees waived for all conference. included papers. • Reduced EI and CEP manuscript • Complimentary conference regis- submission fees for non- tration for either or both conference manuscripts. conferences if you are an • Discount on International Atlantic Institutional Member affiliate and Economic Society membership. organize a session. -

Economic Associations the Union of National in Japan

No.29 ISSN 0289 - 8721 NAL ECO IO N T O Information Bulletin of A M N I C F A O The Union of National S N S O O I C N I A Economic Associations U T E I O H T N S in Japan 日本経済学会連合 2009 Editorial Committee Tomonori NAKAMURA, Meiji University Yasuyoshi KUROKAWA, Senshu University Jota ISHIKAWA, Hitotsubashi University Shozo INOUYE, Rikkyo University Yoshio MAYA, Nihon University Yuji OSHITA, Hosei University Yoshiharu KUWANA, J.F.Oberlin University Koji YOSHIMURA, Meiji University Yuji YUI, Seijo University Toshio UEMURA, Asia University Hiroshi SAIGO, Waseda University Kazusei KATO, Nihon University Directors of the Union President Kenichi ENATSU, Waseda University Yasuo OKAMOTO, University of Tokyo Toshio KIKUCHI, Nihon University Mitsuhiko TSURUTA, Meiji University Yasuhiro OGURA, Toyo University Hiroshi OTSUKI, Waseda University Ryuhei WAKASUGI, Kyoto University Fumihiko HIRUMA, Waseda University Yukiko FUKAGAWA, Waseda University Kenji AKIYAMA, Kanagawa University Secretary General Masataka OTA, Waseda University Auditor Yoshiaki TAKAHASHI, Chuo University Takashi HASHIMOTO, Aoyama Gakuin University Emeritus Takashi SHIRAISHI, Keio University Osamu NISHIZAWA, Waseda University THE UNION OF NATIONAL ECONOMIC ASSOCIATIONS IN JAPAN 日本経済学会連合 The Union of National Economic Associations in Japan, established in 1950, celebrated its 50th anniversary in 2000, as the sole nationwide federation of associations of scholars and experts on economics, commerce, and business administration. In order to obtain membership an association is subject to an examination of its academic work. As of 2009, the Union had a membership of 63 associations, as listed on pp.100-120. The aims and objectives of the Union are to support the scholarly activities of its member associations and to promote academic exchanges both among members themselves, and between Japanese and academic societies overseas. -

RIETI Highlight Vol.63

2017 SPECIAL EDITION 63 The Research Institute of Economy, Trade and Industry (RIETI) is a policy think tank established in 2001. Our mission is to conduct theoretical and empirical research, Special BBL Seminar by the President to maximize synergies with those engaged in policymaking, and to make policy proposals based on evidence derived from such research activities. For such activities, RIETI has developed an excellent reputation both in Japan and abroad. Website: http://www.rieti.go.jp/en/ Law and Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/en.RIETI Economics on Market Quality RIETI Policy Symposium Frontier of Inter-firm Network Analysis: Makoto Yano Power of network and geographical friction President and Chief Research Ofcer (CRO), RIETI Research Activities RIETI Research Framework for the Fourth Medium-Term Period Message from the Chairman 2017 Special Edition 63 he global economy remains sluggish in part due to an oversupply Contents of oil and other resources and their resulting low prices. In the meantime, declining birthrates and aging populations in major T countries are weakening their potential growth rates due to Message from the Chairman 1 structural reasons. It has become increasingly necessary to undertake monetary and fiscal policies and structural reform to reinvigorate economies. SPECIAL BBL SEMINAR Law and Economics on Market Quality 2 One example is the Japanese economy, which has been seesawing up BY THE PRESIDENT and down despite favorable conditions such as monetary easing and low oil prices. Employment and income figures continue to improve, whereas the SPECIAL REPORT RIETI-CEPR Brexit Symposium in Japan Brexit: On the future of the UK and the global economy 7 slack global economy and strong yen have constrained the growth of exports and production. -

Kyoto University

KIER 2016-2017 Overview of Institute of Economic Research Kyoto University Kyoto University CONTENTS ◆2016-2017 Overview of Institute of Economic Research Kyoto University Foreword ……………………………………………………………………………………………01 Organization and Research Staff………………………………………………………………02 Actual Staff…………………………………………………………………………………………03 List of Directors……………………………………………………………………………………03 List of Professors Emeriti…………………………………………………………………………03 Research Divisions and Centers Economic Information Analysis Division …………………………………………………04 Economic Institution Division…………………………………………………………………04 Strategic Economic Studies Division………………………………………………………05 Finance Research Division……………………………………………………………………05 Research Center for Economics of Complex Systems…………………………………06 Research Center for Advanced Policy Studies …………………………………………06 Contemporary Economic Analysis Division (Visiting Researchers)…………………07 Joint Usage / Research center “International Joint Research Center of Advanced Economic Theory” …………07 International Research Unit of Integrated Complex System Science (IRU-ICSS) …07 Social Science Unit for Research and Education…………………………………………08 International Research Unit of Advanced Future Studies (IRU-AFS)…………………08 Research Unit for Development of Global Sustainability…………………………………08 ICAM Kyoto Branch………………………………………………………………………………08 Social Contribution ………………………………………………………………………………09 Track Record………………………………………………………………………………………16 Library ………………………………………………………………………………………………18 Finances ……………………………………………………………………………………………19 Chronological Table………………………………………………………………………………20 -

Endogenous Exchange Rate Fluctuations Under the Flexible Exchange Rate Regime

This PDF is a selection from an out-of-print volume from the National Bureau of Economic Research Volume Title: Macroeconomic Linkage: Savings, Exchange Rates, and Capital Flows, NBER-EASE Volume 3 Volume Author/Editor: Takatoshi Ito and Anne Krueger, editors Volume Publisher: University of Chicago Press Volume ISBN: 0-226-38669-4 Volume URL: http://www.nber.org/books/ito_94-1 Conference Date: June 17-19, 1992 Publication Date: January 1994 Chapter Title: Endogenous Exchange Rate Fluctuations under the Flexible Exchange Rate Regime Chapter Author: Shin-ichi Fukuda Chapter URL: http://www.nber.org/chapters/c8533 Chapter pages in book: (p. 203 - 225) 8 Endogenous Exchange Rate Fluctuations under the Flexible Exchange Rate Regime Shin-ichi Fukuda 8.1 Introduction In the past two decades, we have experienced in the foreign exchange mar- kets significant temporary fluctuations in the exchange rates of major currenc- ies. For example, by plotting the movements of the yeddollar exchange rate after 1973, we can see a clear downward trend in this exchange rate in the long run. However, we can also see that the trend was not monotonic in the short run and that there were significant temporary fluctuations around the trend (see fig. 8.1). The purpose of this paper is to investigate why the exchange rate shows such significant temporary fluctuations. The model of the following analysis is based on a model of money in the utility function with liquidity-in- advance. Following Fukuda (1990), we investigate the dynamic properties of a small open economy version of this monetary model. The methodology used in the following analysis is an application of the theory of “chaos.” In the previous literature, Benhabib and Day (1982), Day (1982, 1983), and Stutzer (1980) are the first attempts to study chaotic phe- nomena in economic models. -

Shuhei TAKAHASHI

Curriculum Vitae October 2020 Shuhei TAKAHASHI Office Address Institute of Economic Research Kyoto University Yoshida Honmachi, Sakyo-ku Kyoto, 606-8501, Japan Email: [email protected] Homepage: https://sites.google.com/site/shuheitakahashi Employment Associate Professor, Institute of Economic Research, Kyoto University, June 2017-present Assistant Professor, Institute of Economic Research, Kyoto University, July 2012-May 2017 Other Positions Research Fellow, The Canon Institute for Global Studies, January 2019-present Visiting Associate Professor, University of Tokyo, July 2018-March 2019 Education Ph.D., Economics, The Ohio State University, June 2012 M.A., Economics, The Ohio State University, August 2007 M.A., Economics, University of Tokyo, March 2006 B.A., Integrated Human Studies, Kyoto University, March 2004 Dissertation “Essays on Business Cycles and Micro-Level Regularities” Dissertation Supervisors: Bill Dupor and Aubhik Khan Areas of Specialization Research: Macroeconomics, Computational Economics, Japanese Economy Graduate Teaching: Macroeconomics, Computational Economics Undergraduate Teaching: Macroeconomics, Japanese Economy, Money and Banking Published Papers “A Note on the Uniqueness of Steady-State Equilibrium under State-Dependent Wage Setting,” Macroeconomic Dynamics, forthcoming. “Time-Varying Wage Risk, Incomplete Markets, and Business Cycles,” Review of Economic Dynamics, 37, 195-213, 2020. Shuhei TAKAHASHI Page 1/5 Curriculum Vitae October 2020 “The Effectiveness of Consumption Taxes and Transfers as Insurance against Idiosyncratic Risk,” (with Tomoyuki Nakajima), Journal of Money, Credit, and Banking, 52 (2-3), 505-530, 2020. “The Optimum Quantity of Debt for Japan,” (with Tomoyuki Nakajima), Journal of the Japanese and International Economies, 46, 17-26, 2017. “State Dependency in Price and Wage Setting,” International Journal of Central Banking, 13 (1), 151-189, 2017. -

K I E R Overview of Institute of Economic Research

K I E R Overview of Institute of Economic Research Kyoto University 2020 - 2021 京都大学 経済研究所 概要2020ー 2021 Overview of Institute of Economic Research Kyoto University 2020 - 2021 京都大学 経済研究所 Foreword 概要2020ー 2021 K I E R For close to half a century, the Kyoto Institute of Economic Research (KIER) has been a leader in Japan in the sphere of fundamental scientic economics, with a focus on theoretical economics and Overview of Institute of Economic Research econometrics. Moreover, the Institute has recently increased its emphasis on research in the sphere of applied scientic aspects of economics, and has gained a strong reputation for its positive progress in Kyoto University 2020 - 2021 policy assessment and policy recommendations. KIER conducts prominent research in the eld of economics at the international level, and our mission is to contribute to the further development of the eld. Each member of the Institute aims to be a pioneer CONTENTS at the front lines of international research, and our research team works with the primary goal of leading the eld. For instance, in terms of number of research papers published in international journals per researcher and the frequency of their citations in various scholarly publications, KIER, when ranked together with other economic institutes and the Graduate School of Economics (Faculty of Economics), Foreword …………………………………………………………………………………………01 maintains one of the top positions among domestic academic institutions specializing in economics. The Organization and Research Sta ………………………………………………………………02 -

Last Nm»«Suffix De»

Western Economic Association International 10th Biennial Pacific Rim Conference Preliminary Program Hosted by Keio University Graduate Schools of Economics and of Business and Commerce, the Tokyo Center for Economic Research, and the Keio-Kyoto Joint Global COE Program Key for Participating Allied Societies University of Economics, and Arkadiusz Maciuk, Wroclaw University of Economics Multidimensional Evaluation of Quality of Educational Services ABDE .......... Brazilian Association of Law and Economics Discussants: from above participants AsLEA ......... Asian Law and Economics Association ATTSS ......... Association of Transport, Trade, and Service Studies IBEFA ......... International Banking, Economics, and Finance [4] 3:15–5:00 p.m. Association TOPICS IN MONETARY THEORY AND POLICY IEFS Japan ... International Economics and Finance Society Japan Chair: Nicholas Apergis, University of Piraeus JARMS ........ Japan Risk Management Society Papers: Nicholas Apergis, University of Piraeus, and Christina JHEA ........... Japan Health Economics Association Christou, University of Piraeus NAASE ........ North American Association of Sports Economists The Bank Lending Channel and Monetary Policy Rules: The Case SEEPS ......... Society for Environmental Economics and Policy of the Zero Lower Bound Studies Jane M. Binner, University of Sheffield, Shu Heng Chen, National Chengchi University, Barry E. Jones, Binghamton University, and Sessions without an organizer listed are volunteer sessions Ke-Hung Lai, Financial Supervisory Commission Taipei assembled by a Screening Committee, Session Consultants, and the Admissable Monetary Aggregates for Taiwan WEAI Executive Office from individual volunteer submissions. Fabio Franch, European Central Bank The European Correspondent Banking Business Yasuo Nishiyama, Woodbury University The Endogenous Money Supply Revisited Discussants: Aaron L. Jackson, Bentley University Thursday, March 14 Yasuo Nishiyama, Woodbury University Jane M. Binner, University of Sheffield [1] 1:15–2:45 p.m. -

2 019 O Verview of in Stitu Te of E Co Nom Ic R Esearch K Yoto U N Iversity

2018-2019 Overview of Institute of Economic Research 2018KIER -2019Overview of Institute of Economic Research Kyoto University Kyoto University 2018-2019 Overview of Institute of Economic Research Kyoto University Kyoto Research Economic of Institute of Overview 2018-2019 Foreword C O N T E N T S ◆2018-2019 Overview of Institute of Economic Research Kyoto University Satoshi Mizobata, Director Kyoto Institute of Economic Research For close to half a century, the Kyoto Institute of Economic Research (KIER) has been a leader in Japan in the sphere of fundamental scientific economics, with a focus on theoretical economics and econometrics. Foreword………………………………………………………………………………………………01 Moreover, the Institute has recently increased its emphasis on research in the sphere of applied scientific aspects of economics, and has gained a strong reputation for its positive progress in policy assessment and Organization and Research Staff …………………………………………………………………02 policy recommendations. KIER conducts prominent research in the field of economics at the international level, and our mission is Actual Staff……………………………………………………………………………………………03 to contribute to the further development of the field. Each member of the Institute aims to be a pioneer at the front lines of international research, and our research team works with the primary goal of leading the field. For instance, in terms of number of research papers published in international journals per researcher List of Directors………………………………………………………………………………………03 and the frequency of their citations in various scholarly publications, KIER, when ranked together with other economic institutes and the Graduate School of Economics (Faculty of Economics), maintains one of List of Professors Emeriti …………………………………………………………………………03 the top positions among domestic academic institutions specializing in economics. -

14 SAET Conference on Current Trends in Economics WASEDA University August 19-21, 2014

14TH SAET CONFERENCE 14th SAET Conference on Current Trends in Economics WASEDA University August 19-21, 2014 CONTENTS Welcome……………………………………………………………………………………………..…… 2 Conference Information: Registration and Internet Access………………………………………………. 2 Maps & Local Information……………………………………………………………………………….. 3 Program Committee………………………………………………………………………………………. 5 Local Organizing Committee……………………………………………………………………………... 5 Session Organizers………………………………………………………………………………………... 5 Program Summary………………………………………………………………………………………… 7 Plenary Talk/Tutorial Details……………………………………………………………………………… 10 Satellite Conference/Workshops………………………………………………………………………….. 11 Parallel Session Details……………………………………………………………………………………. 12 List of Participants………………………………………………………………………………………… 33 WELCOME On behalf of the Society for the Advancement of Economics Theory, we are pleased to welcome you to Waseda University on the occasion of the 14th SAET Conference. We wish to express gratitude to various institutions that made this conference possible: the Graduate School of Economics, Waseda University, Japan Center for Economic Research, Tokyo Center of Economic Research, Japan Society for Proportion of Science, and the University of Iowa. Many thanks to the people who generously contributed to the success of this event, in particular, the local organizing committee and session organizers. Special thanks to Renea Jay and Rumi Ohata for their attention to detail and preparation of this conference. We hope you enjoy the conference and we wish you a pleasant stay in Tokyo. Mamoru Kaneko and Nicholas Yannelis CONFERENCE INFORMATION Registration: Name tags and conference programs are available in Building 10, Rooms 101-102 Internet access (Wi-Fi) is available in Building 10, Rooms 306-308 2 Takadanobaba Sta. Waseda Sta. Iidabashi Sta. Akihabara Sta. JR Sobu line Shinjuku Sta. Metro Tozai line J R Tokyo Sta. Y a m an ote line Access to the SAET 2014 conference at Waseda Campus (1): 10 minutes walk from Waseda Sta.(Tokyo Metro Tozai Line) Metro Tozai Line to Waseda Sta. -

2016-2017 Overview of Institute of Economic Research Kyoto University

KIER 2016-2017 Overview of Institute of Economic Research Kyoto University Kyoto University CONTENTS ◆2016-2017 Overview of Institute of Economic Research Kyoto University Foreword ……………………………………………………………………………………………01 Organization and Research Staff………………………………………………………………02 Actual Staff…………………………………………………………………………………………03 List of Directors……………………………………………………………………………………03 List of Professors Emeriti…………………………………………………………………………03 Research Divisions and Centers Economic Information Analysis Division …………………………………………………04 Economic Institution Division…………………………………………………………………04 Strategic Economic Studies Division………………………………………………………05 Finance Research Division……………………………………………………………………05 Research Center for Economics of Complex Systems…………………………………06 Research Center for Advanced Policy Studies …………………………………………06 Contemporary Economic Analysis Division (Visiting Researchers)…………………07 Joint Usage / Research center “International Joint Research Center of Advanced Economic Theory” …………07 International Research Unit of Integrated Complex System Science (IRU-ICSS) …07 Social Science Unit for Research and Education…………………………………………08 International Research Unit of Advanced Future Studies (IRU-AFS)…………………08 Research Unit for Development of Global Sustainability…………………………………08 ICAM Kyoto Branch………………………………………………………………………………08 Social Contribution ………………………………………………………………………………09 Track Record………………………………………………………………………………………16 Library ………………………………………………………………………………………………18 Finances ……………………………………………………………………………………………19 Chronological Table………………………………………………………………………………20 -

RIETI Annual Report 2019/4-2020/3

Research Institute of Economy, Trade and Industry, IAA Industry, and Report Annual April Trade Economy, of Research Institute Research Institute of Economy, Trade and Industry, IAA Annual Report April 2019 - March 2020 2019 - March 2020 Research Institute of Economy, Trade and Industry, IAA 11th oor, Annex, Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry (METI) 1-3-1 Kasumigaseki, Chiyoda-ku, Tokyo 100-8901 JAPAN Phone: +81-3-3501-1363 Fax: +81-3-3501-8577 email: [email protected] Website: https://www.rieti.go.jp/en/ @en.RIETI @RIETI english Organization Chart Contents Messages from the Chairman and the President 1 Auditor Chairman Overview of FY2019 Activities 2 About RIETI Research Framework The Research Institute of Economy, Trade and Industry (RIETI), for RIETI’s Fifth Medium-Term Plan 8 an incorporated administrative agency, was established on April 1, Vice Chairman Office of Internal Audit President and CRO Research Activities 9 2001 to conduct extensive policy research and formulate policy recommendations. Leveraging its location in Kasumigaseki, RIETI Research Programs / Projects 10 takes full advantage of the synergy among policymakers, researchers, Vice President Research Papers 48 industry leaders, and other stakeholders, and has developed an excellent Public Relations Activities 63 reputation both in Japan and abroad for its evidence-based, theoretical and empirical research, and its recommendations on a diverse array of Organizational Operation Publications 64 Research Activities issues regarding the economy, industry, and society. and Management Website 66 RIETI has set up an overall framework of research themes to PR Materials 67 respond to policymaking needs. Within this overall framework, fellows Administration Group undertake their own research in a free atmosphere, building organic Symposiums 68 • General Administration linkages with other current research.