Yale Law School 2012–2013

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Yale Law School 2010–2011

BULLETIN OF YALE UNIVERSITY BULLETIN OF YALE UNIVERSITY Periodicals postage paid New Haven ct 06520-8227 New Haven, Connecticut Yale Law School 2010–2011 Yale Law School Yale 2010–2011 BULLETIN OF YALE UNIVERSITY Series 106 Number 10 August 10, 2010 BULLETIN OF YALE UNIVERSITY Series 106 Number 10 August 10, 2010 (USPS 078-500) The University is committed to basing judgments concerning the admission, education, is published seventeen times a year (one time in May and October; three times in June and employment of individuals upon their qualifications and abilities and a∞rmatively and September; four times in July; five times in August) by Yale University, 2 Whitney seeks to attract to its faculty, sta≠, and student body qualified persons of diverse back- Avenue, New Haven CT 0651o. Periodicals postage paid at New Haven, Connecticut. grounds. In accordance with this policy and as delineated by federal and Connecticut law, Yale does not discriminate in admissions, educational programs, or employment against Postmaster: Send address changes to Bulletin of Yale University, any individual on account of that individual’s sex, race, color, religion, age, disability, PO Box 208227, New Haven CT 06520-8227 status as a special disabled veteran, veteran of the Vietnam era, or other covered veteran, or national or ethnic origin; nor does Yale discriminate on the basis of sexual orientation Managing Editor: Linda Koch Lorimer or gender identity or expression. Editor: Lesley K. Baier University policy is committed to a∞rmative action under law in employment of PO Box 208230, New Haven CT 06520-8230 women, minority group members, individuals with disabilities, special disabled veterans, veterans of the Vietnam era, and other covered veterans. -

City of Elk Grove City Council Staff Report

AGENDA ITEM NO. 10.1 CITY OF ELK GROVE CITY COUNCIL STAFF REPORT AGENDA TITLE: Consider a resolution dispensing with the formal request for proposal procedures pursuant to Elk Grove Municipal Code section 3.42.188(B)(3) and authorizing the City Manager to execute a contract with Sacramento Regional Transit District (SacRT) to provide the City’s fixed-route local and commuter transit services, Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) paratransit services, and supporting transit maintenance operations; and execute a Second Amendment to the Service Agreement between SacRT and the City of Elk Grove (C-17-290) modifying the proportionate share payment requirements upon execution of the contract with SacRT to provide the City’s transit services and maintenance operations MEETING DATE: February 27, 2019 PREPARED BY: Michael Costa, Transit System Manager DEPARTMENT HEAD: Robert Murdoch, P.E., Public Works Director/ City Engineer RECOMMENDED ACTION: Staff recommends that the City Council adopt a resolution: 1. Dispensing with the formal request for proposal procedures pursuant to Elk Grove Municipal Code section 3.42.188(B)(3) and authorizing the City Manager to execute a contract with Sacramento Regional Transit District (SacRT) to provide the City’s fixed-route local and commuter transit services, Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) paratransit services, and supporting transit maintenance operations; and 1 Elk Grove City Council February 27, 2019 Page 2 of 6 2. Authorizing the City Manager to execute a Second Amendment to the Service Agreement between SacRT and the City of Elk Grove (C-17- 290), modifying the proportionate share payment requirements upon execution of the contract with SacRT to provide the City’s transit services and maintenance operations. -

Living Simultaneity

Living Simultaneity Simultaneity Living Semi-secular individuals, those who are neither religious nor unreligious, seldom get the attention of scholars of religion. Here, however, they stand at the center. Th e interviewees live in the same Stockholm neighborhood and it is their ways of talking about and relating to religion that is analyzed and described. Simultaneity is one particular feature in the material. Th is concept emphazises a ‘both and’ approach in: the way the respon- dents ascribe meaning to the term religion; how they talk about themselves in relation to diff erent religious designations and how they interpret experiences that they single out as ‘out-of-the- ordinary’. Th ese simultaneities are explained and theorized through analyses focusing on intersubjective and discursive processes. Th is work adds to a critical discussion on the supposedly far-reaching secularity in Sweden on the one hand and on the incongruence and inconsistency of lived religion on the other. In relation to theorizing on religion and religious people, this study off ers empirical material that nuance a dichotomous under- standing of ‘the religious’ and ‘the secular’. In relation to method- ology it is argued that the salience of simultaneity in the material shows that when patterns of religiosity among semisecular Swedes are studied there is a need to be attentive to expressions of com- plexity, contradiction and incongruity. Ann af Burén Living Simultaneity On religion among semi-secular Swedes Södertörns högskola SE-141 89 Huddinge Ann af Burén -

The Study of Language This Best-Selling Textbook Provides an Engaging and User-Friendly Introduction to the Study of Language

This page intentionally left blank The Study of Language This best-selling textbook provides an engaging and user-friendly introduction to the study of language. Assuming no prior knowledge of the subject, Yule presents information in short, bite-sized sections, introducing the major concepts in language study – from how children learn language to why men and women speak differently, through all the key elements of language. This fourth edition has been revised and updated with twenty new sections, covering new accounts of language origins, the key properties of language, text messaging, kinship terms and more than twenty new word etymologies. To increase student engagement with the text, Yule has also included more than fifty new tasks, including thirty involving data analysis, enabling students to apply what they have learned. The online study guide offers students further resources when working on the tasks, while encouraging lively and proactive learning. This is the most fundamental and easy-to-use introduction to the study of language. George Yule has taught Linguistics at the Universities of Edinburgh, Hawai’i, Louisiana State and Minnesota. He is the author of a number of books, including Discourse Analysis (with Gillian Brown, 1983) and Pragmatics (1996). “A genuinely introductory linguistics text, well suited for undergraduates who have little prior experience thinking descriptively about language. Yule’s crisp and thought-provoking presentation of key issues works well for a wide range of students.” Elise Morse-Gagne, Tougaloo College “The Study of Language is one of the most accessible and entertaining introductions to linguistics available. Newly updated with a wealth of material for practice and discussion, it will continue to inspire new generations of students.” Stephen Matthews, University of Hong Kong ‘Its strength is in providing a general survey of mainstream linguistics in palatable, easily manageable and logically organised chunks. -

Creating a Better Way to Live

CREATING A BETTER WAY TO LIVE 2019 CORPORATE RESPONSIBILITY REPORT AT AVALONBAY COMMUNITIES, OUR PURPOSE IS CREATING A BETTER WAY TO LIVE — FOR OUR RESIDENTS, OUR ASSOCIATES, OUR SHAREHOLDERS, THE COMMUNITIES IN WHICH WE DO BUSINESS AND OUR PLANET AT LARGE. Achieving this purpose means being aware of the full impact of our activities and managing our business with an eye on the future. It means remaining true to the long-term wellbeing of all of our stakeholders, broadly defined. As a real estate investment trust (REIT), we are owners and investors for the long term, allowing us to consider the full life cycle impact of the decisions we make every day. With this in mind, our goal is to build and operate much more than buildings. The cities and suburbs in our core markets across the country are reinventing themselves through higher density, amenity-rich living. They are offering residents more options for sustainable ways to live, from green buildings and walkable neighborhoods to better transit and commuting alternatives, and they are moving to a low-carbon emission future. We’re proud to be at the forefront of this reinvention, creating communities that achieve long-term environmental efficiency and foster better living far beyond their walls. Communities through which we make our core values visible: a commitment to integrity, a spirit of caring and a focus on continuous improvement. Realizing this vision is an ongoing journey and is not always easy. But for us, it’s always right. 1 FROM THE CEO 2019 was another productive year for AvalonBay and our stakeholders — investors, residents, associates and the communities where we do business. -

Fun Halloween Events and Fall Fests Planned In

DAYLIGHT SAVING TIME ENDS SUNDAY; HALLOWEEN IS TUESDAY Ozark COunTy ¢ Times 75 GAINESVILLE, Mo. www.ozArkcouNtytimes.coM wEdNESdAy, octobEr 25, 2017 Gainesville man charged with parking lot stabbing incident Kevin Robinson, 28, of Gainesville is being held in the Ozark County Jail on a $25,000 cash- only bond, charged in connection with the Oct. 21 stabbing of 24-year-old Robert Chambers in Gainesville’s Town & Country Super- market parking lot. Robinson Robinson, who was arraigned Tuesday before Associate Judge Cynthia MacPherson, is scheduled to return to court for a criminal set- ting on Nov. 14. If convicted, he could face 10 to 30 years in prison for the class A felony assault charge. Robinson was arrested Monday night; how- ever, Monday morning, Ozark County Sheriff Darrin Reed told the Times that Chambers, the victim, was not cooperative with officers, mak- Darla Sullivan and her grandkids, from left Jese Landry, Claire Turner, Jayce Turner and Jack ing the investigation challenging. Landry, enjoyed the 2016 Ozark County Trunk-or-Treat event on the Gainesville square. This “We’re still investigating, but it’s kind of year’s event is scheduled for 6 to 8 p.m. Tuesday, Oct. 31. hard to put a case together in a situation like this without cooperation from the victim,” Reed said Monday. However, according to a probable cause statement filed in the case, another wit- ness at Town & Country spoke with Ozark County Deputy Nick Jones and told the officer More fun Halloween events and he saw Robinson stab Chambers. Reed said Jones was dispatched to Town & Country at 5:16 p.m. -

Revise Income Tax Laws, Morgenthau Advises Committee

w m m A ie m b a i l t cnooLAxicHf i V Mr th» MMrtfe «< 5,341 Mwmbrr «f Ike AoAt Pufiien o f CWrwiletloM, ilmtrhfatfr VOL. LIIL, NO. 64. (Oaeatfled AdrertiilBg oa Page 16.). MANCHESTER, CONN., FRIDAY, DECEMBER ^5, 1933. (EIGHTEEN PAGES) i>---------------- IJEATH ANSWERS ■■■< > FOUR M U O N MOTHER’S APPEAL A Roosevelt Conference Wilii Santa Claus UNDYS REACH REVISE INCOME TAX Doctors Not Allowed To End IDLE ARE NOW the Sufferinsrs of Deformed SAN PEDRO ON M A m WAGES Nine Months Old Child. H O M E m H O P LAWS, MORGENTHAU Toronto, Dec. 16.—(AP)-r Nlne months of suffering was ended today with the death of a Toronto baby whose mother ADVISES COMMITTEE Goal Set by President b had appealed to doctors to end Reach D(Mniiiicaii Repoblic its life. Reached — May Carry 'N^ctim o f hydracepbalus in Short Flight from Puer which caused its head to grow ACCDENTAL DEATH Treasory Head Fa?ort Low to three times normal size, the die C. W. A. Plan Into the Infant became unconscious to Rico— To Continoe early this week. Pressure on er Tax on Earned Income Spring Months. the brain piaraljrzed all the vital Trip Tomorrow. THEORY IS PROBED centers. and from Income on b - Dr. Luke Testey,, surgeon, said it was “fortunate the par WuhlngtoD, Dec. 16,— (A P )—The ents are sensible about it; that San Pedro, Dominican Republic, State Police Not Satisfied Testments— Also WonU Civil Work* Adminiftratlon eald to* the mother Is bearing up well Dec. -

An Exhibition of Works by Recipients of the Annual Awards in the Visual Arts

AWARDS IN THE VISUAL ARTS AWARDS I N THE VISUAL ARTS 1)1 :he AEiXiQiiOiQd ib^i^ttatOi/iln-tlpcPtr^dQt AlilQlTJiX^los Alfonzo. in 2015 https://archive.org/details/awardsinvisualar10sout AWARDS IN THE VISUAL ARTS lO CARLOS ALFONZO STEVE BARRY PETAH COYNE T"^' 11 LABAT C/ ' :^>. LEfl^.^ AITZ ADRIAN PAPER A. _ . _.HE-F.^ ^„^^LL JESSICA S EXHIBITION TOUR 12 June through 2 September, 1991 Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden Smithsonian Institution Washington, DC 14 September through 1 December, 1991 Albuquerque Museum of Art, History and Science Albuquerque, New Mexico 15 December, 1991 through 26 January, 1992 The Toledo Museum of Art Toledo, Ohio Spring of 1992 The BMW Gallery New York, New York Selections of AVA 10 Exhibition FUNDERS The Awards in the Visual Arts program is funded by BMW of North America, Inc. Woodcliff Lake, New Jersey The Rockefeller Foundation New York, New York AVA is funded in part by a grant from the National Endowment for the Arts, a federal agency, Washington, D.C. The program was founded and is administered by the Southeastern Center for Contemporary Art Winston-Salem, North Carolina I I I I I"- CONTENTS FOREWORD 8 by Ted Potter CATALOG ESSAY 9 by Kathryn Hixson CARLOS ALFONZO 24 STEVE BARRY 32 PETAH COYNE 40 JAMES HAYWARD 50 TONY LABAT 56 CARY S. LEIBOWITZ 66 ADRIAN PIPER 74 ARNALDO ROCHE-RABELL 86 KAY ROSEN 92 JESSICA STOCKHOLDER 102 EXHIBITION CHECKLIST no AVA GUIDELINES/PROCEDURES 114 AVA RECIPIENTS 1981 90 116 AVA lO JURY 118 AVA EXECUTIVE COMMITTEE 119 AVA NATIONAL PROFESSIONAL COUNCIL 120 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS 122 FOREWORD The Awards in the Visual Arts tenth annual exhibition will open at the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden. -

The History of Child Welfare in Louisiana, 1850-1960

This dissertation has been 69- 11,681 microfilmed exactly as received MORAN, Sr., Robert Earl, 1921- THE HISTORY OF CHILD WELFARE IN LOUISIANA, 1850 - 1960. The Ohio State University, Ph.D., 1968 History, modern Social Work University Microfilms, Inc., Ann Arbor, Michigan THE HISTORY OF CHILD WELFARE IN LOUISIANA, 1850 - I960 DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Robert Earl Moran, Sr., B. S., M. A. ******** The Ohio State University 1968 Approved by / / Ba S w . A dviser Department of H is to ry ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The author wishes to express his grateful appreciation to the librarians of the Louisiana Room of Louisiana State Library and the Louisiana State University Library, the Department of Archives of the Louisiana State University Library, and the Howard Memorial Library of Tulane University. Especially does the author thank his adviser, Dr. Robert H. Bremner whose constant guidance and encouragement helped to bring this work to its completion. i i VITA July 24, 1921 Born - Columbus, Ohio 1944 B.S., The Ohio State University 1944-1946 . Teacher at Palmer Memorial Institute, Sedalia, North Carolina 1947 M.S., The Ohio State University 1948-1959 . Instructor, Allen University, Columbia, South Carolina 1959 Instructor, Southern University, Baton Rouge, Louisiana FIELDS OF STUDY Major Field: History Studies in Political and Social History of the United States, 1850-1900. Professor Francis P. Weisenburger Studies in Political and Social History of the United States, 1900-present. Professors Foster Rhea Dulles and Robert H. Bremner Studies in United States Foreign Relations. -

U.S., Soviet to Sell Liquor from Noon to 9 P.M

‘•r, V . .■ * a ' . I ‘ I' ' , ' K ■ : .^ ' : ' - V"., :f ". TVT.DNKSDAY, JULY 20, 19B| Average Oidly Net PreMi Ran 5rWcNTY ^ Par th« W«6k 1B«M V'*'' • ■. ^ •■ ‘ '1 iOanrltPatpr lenfttfng 1$rraUk • X ' :. y Jmix 18, 185$ . sals prditlanct. During ppblic dis 1 1 ^ 4 1 ' , rise ami eng Board Gets, Files cussions over the issua, the Rev. DoD Show TMirght r •< Bm ABdlt : i , ‘W.nMBrBUri lAb^irtTdwn Dr. Edgar then said the church •C OnBlattM Sunday Sale Bid groupe .wt^d bring the question of . l-‘ A doll ahow Will be held at having a "dry” town beford the Mioiekester -«A City o f Vittago ChahS^ Mfurtiiiit ~ rr- ” — '— *~~ all 10 playgTouhda thta'evening f iM it n u n t wt»o mr« i««neet«d - a % , i' . voters. Ktth tti* P «i*h fVdUral O om m ltu; at 6:45 p.m. All children In- A petition cslling fo^ sn-. ordi The church interests do not ap •|| IM I I. r V II' II I)iu ifl|[j i r tereated In entering their dolla HALE’S JULY VOL.LXXIV,NO,J47 hoM • nie«Unr tonicht at • :SQ pear to be pursuing that strate^ (TWENTY PAGB3) should go to the nearest play nance which wilt permit the sslCi MANCHESTER, CONN., THURSDAY, JULY 21,1155 <ClaMUM Aevardiiag oa Pag* 18) PRICE •t tin firehouM at Ui« corner o f' of liquor on Sunday was received now. In any case the town clerk -yrmim and HiUlard 8ta. ground. Awards will be ^ven has said that both quc.xtions can^ to the winners. -

Covert Crooners Ken Jeong, Nicole Scherzinger, Nick Cannon, Jenny Mccarthy and Robin Thicke from “The Masked Singer”

VALENTINE’S DAY SPECIAL Select Women’s Rings & Tools off 25% 1600 S. Main St. Ned’s Pawn Laurinburg, NC 28352 February 1 - 7, 2020 JEWELRY • AUDIO (910) 276-5310 Baby, It’s Warm Inside! We Deliver! Pricing Plans Available Covert crooners Ken Jeong, Nicole Scherzinger, Nick Cannon, Jenny McCarthy and Robin Thicke from “The Masked Singer” 910 276 7474 | 877 829 2515 12780 S Caledonia Rd, Laurinburg, NC 28352 serving Scotland County and surrounding areas Joy Locklear, Store Manager 234 E. Church Street, Laurinburg NC 910-277-8588 www.kimbrells.com Page 2 — Saturday, February 1, 2020 — Laurinburg Exchange “Serving Scotland County 38 years” Musical mystery: Season 3 of ‘The Masked Singer’ Danny Caddell, Agent premieres after Super Bowl LIV 915 S Main Street The Oaks Professional Building PageLaurinburg, 2 — Saturday, NC 28352 February 1, 2020 — Laurinburg Exchange Bus: 910-276-3050 [email protected] Musical mystery: Season 3 of ‘The Masked Singer’ premieres after Super Bowl LIV Thank you for your loyalty. We appreciate you. FOR NEW ACCOUNTS UP SAVE TO $100 ON YOUR FIRST IN-STORE PURCHASE* when you open and use a new Lowe’s Advantage Card. Minimum purchase required. Offer ends 2/1/20. *Cannot be combined with any other offer. Coupon required. Lowe's of Laurinburg By Breanna910 HenryUS 15-401 By-Pass |catch Laurinburg, is that the NC celebrities 28352 are TV Media (910) 610-2365wearing elaborate costumes that conceal their identities. Referred to here is an absolute smorgasbord only by the name of their costume, a TBy ofBreanna reality television Henry to choose catchcontestant is that is the not celebrities unmasked are until TVfrom Media these days, and performance wearingthey are votedelaborate off of costumes the show, that and competitions make up a large per- despiteconceal Nicktheir Cannon’s identities. -

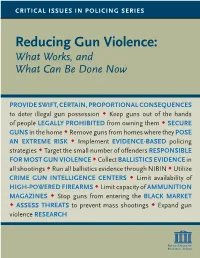

Reducing Gun Violence: What Works, and What Can Be Done Now

CRITICAL ISSUES IN POLICING SERIES Reducing Gun Violence: What Works, and What Can Be Done Now PROVIDE SWIFT, CERTAIN, PROPORTIONAL CONSEQUENCES to deter illegal gun possession Keep guns out of the hands of people LEGALLY PROHIBITED from owning them SECURE GUNS in the home Remove guns from homes where they POSE AN EXTREME RISK Implement EVIDENCE-BASED policing strategies Target the small number of offenders RESPONSIBLE FOR MOST GUN VIOLENCE Collect BALLISTICS EVIDENCE in all shootings Run all ballistics evidence through NIBIN Utilize CRIME GUN INTELLIGENCE CENTERS Limit availability of HIGH-POWERED FIREARMS Limit capacity of AMMUNITION MAGAZINES Stop guns from entering the BLACK MARKET ASSESS THREATS to prevent mass shootings Expand gun violence RESEARCH CRITICAL ISSUES IN POLICING SERIES Reducing Gun Violence: What Works, and What Can Be Done Now March 2019 This publication was supported by the Motorola Solutions Foundation. The points of view expressed herein are the authors’ and do not necessarily represent the opinions of the Motorola Solutions Foundation or all Police Executive Research Forum members. Police Executive Research Forum, Washington, D.C. 20036 Copyright © 2019 by Police Executive Research Forum All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America ISBN: 978-1-934485-49-1 Graphic design by Dave Williams. Text photos by Greg Dohler. Contents Acknowledgments ...................................................... 1 Gun Violence Category #3: Intimate Partner Violence (IPV) ..........35 Executive Summary: