The Dead in the Memory Palace: the Detective Work of Memory and Mourning in the Mentalist (Cbs, 2008-)1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

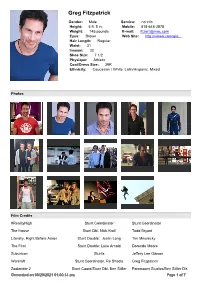

Greg Fitzpatrick

Greg Fitzpatrick Gender: Male Service: no info Height: 5 ft. 8 in. Mobile: 818-648-2878 Weight: 145 pounds E-mail: [email protected] Eyes: Brown Web Site: http://vimeo.com/gre... Hair Length: Regular Waist: 31 Inseam: 32 Shoe Size: 7 1/2 Physique: Athletic Coat/Dress Size: 39R Ethnicity: Caucasian / White, Latin/Hispanic, Mixed Photos Film Credits #RealityHigh Stunt Coordinator Stunt Coordinator The House Stunt Dbl. Nick Kroll Todd Bryant Literally, Right Before Aaron Stunt Double: Justin Long Tim Mikulecky The First Stunt Double: Luke Arnold Dorenda Moore Suburicon Stunts Jeffery Lee Gibson Warcraft Stunt Coordinator, Re Shoots Greg Fitzpatrick Zoolander 2 Stunt Coord/Stunt Dbl. Ben Stiller Paramount Studios/Ben Stiller Dir. Generated on 09/29/2021 01:00:14 pm Page 1 of 7 Luke Lafontaine Night At The Museum 3-The Stunt Dbl. Ben Stiller/Asst. Brad Martin Secret Of The Tomb Coordinator Expelled Stunt Dbl.: Cameron Dallas Kim Koski/Tony Snegoff Godzilla Stunts John Stoneham Jr. The Secret Life Of Walter Mitty Dbl. Ben Stiller Tim Trella The Watch Dbl. Ben Stiller Jack Gill African Gothic Stunt Coordinator The Beautiful Ones Stunts Luke LaFontaine For The Love Of Money Dbl. Hal Ozan Jesse V. Johnson Project Five Stunt Double: David Eigenberg Charlie Brewer Tower Heist Stunt Double: Ben Stiller Jerry Hewitt Real Steel Atom Fight Double Garrett Warren Little Fockers Stunt Double: Ben Stiller Garrett Warren Green Hornet Acting Role / Stunts Andy Armstrong Hawthorne Stunts Kerry Rossal Ironman 2 Stunt Double: Robert Downey Jr. Tom Harper Night At The Museum 2 Stunt Double: Ben Stiller JJ Makaro Angels & Demons Stunts Brad Martin The Soloist Stunt Double: Robert Downey Jr. -

Peter Xifo • SAG-AFTRA

PETER XIFO • Theatrical: Across The Board Talent AgencySAG-AFTRA Inc., ROXANNE CLARK: 323.761.0282 Commercial/Print: The Osbrink Agency, MAUREEN ROSE: 818.760.2488 Voice Over: DPN Talent Agency, JEFF DANIS: 310.432.7800 5’ 8” • Brown Eyes • Salt & Pepper Hair • 185 lbs. WWW.XIFO.NET • PETE @ XIFO.NET • 818.842.5985 FILM: Secret Agent Dingledorf Museum Curator Billy Dickson Miniature The Janitor Samuel Gonzalez Jr. Final Frequency Vic the Vet Tim Lowry Hickok Sam Needham Timothy Woodward Jr. The Gate of Oaks Gabriel Bert Thomas Tolkien’s Road The Wizard Nye Green As Long As You Both Shall Live Peter Peter Macaluso TELEVISION: The Mentalist Guest Star John Showalter Side Quest (reoccurring) Wizard Rob Nelson To Tell the Truth Imposter ABC Television This Giant Beast That is the Global Economy Is Money (Amazon Prime) Ship Captain Lee Farber General Hospital Supporting Larry Carpenter Titanic, Sinking the Myths - Docudrama Capt. Edward J. Smith, RNR Ryan Katzenbach Jimmy Kimmel Live! Principal ABC Studios Tosh.0 Principal Comedy Central The Mona Lisa Myth (on camera & VO) Elder Leonardo da Vinci Jean-Pierre Isbouts COMMERCIALS: Four nationals and multiple regionals as a Principle. Conflicts upon request. VOICE OVER: Journey To Royal (Trailer) Narrator Christopher Johnson Ararat Armenian Brandy - Image Promo Narrator Alexandra Vasilieva Battlestar Galactica (Reoccuring - Video Game) Sinon Quade Dan Bewick Earthquake (VO Dubbing) Erem Monique Carmona Takeda Corporate - Image Promo (3 Spots) Narrator Aki Mizutani Chef’s Table (UN style dubbing) -

Ent Lab Resume

MIKE PEEBLER SAG-AFTRA, AEA TELEVISION Chicago Med Guest Star NBC Perfect Harmony Co-Star NBC Elemental (Pilot) Lead NatGeo Hawaii 5-0 Guest Star CBS The Infamous (Pilot) Guest Star A&E Chicago PD Guest Star NBC Masters of Sex Guest Star Showtime 2 Broke Girls Co-Star CBS NCIS: Los Angeles Co-Star CBS The Young and the Restless Recurring Guest Star CBS Mad Men Co-Star AMC The Mentalist Guest Star CBS Wendell and Vinnie Guest Star Nickelodeon American Horror Story Co-Star FX Medium Co-Star NBC ER Co-Star NBC NUMB3RS Co-Star CBS Las Vegas Co-Star NBC Scrubs Co-Star NBC/Touchstone Television Talk Show with Spike Feresten Co-Star Fox Best Damn Sports Show Period Recurring Sketch Comedy Player Fox Sports Network FILM Hot Bath Stiff Drink William Dillinger Dir: Matthew Gratzner Valkyrie Lieutenant Dir: Bryan Singer A Lonely Place For Dying Lieutenant Roy Hill Dir: Justin Evans Yellow Brook Randy (Supporting) The Vine Studios The New Twenty Mike (Supporting) The Vine Studios Perception James (Featured) Porch Light Pictures Honeyrun Matt (Lead) Sady Productions, LLP Rape of Nia Miles (Lead) Oz Productions THEATER (Partial Listing) Macbeth MacDuff Shakespeare Orange County Hamlet Hamlet Theatricum Botanicum Richard III Duke of Buckingham Shakespeare Orange County Julius Caesar Brutus Theatricum Botanicum Grapes of Wrath Tom Joad Will and Company As You Like It Orlando Theatricum Botanicum Dracula(World Premiere Adaptation) Dr. Seward Theatricum Botanicum Omnium Gatherum (West Coast Premiere) Jeff Theatricum Botanicum The Odyssey Tiresias, Eurylochus Will and Company Pebble In My Shoe (World Premiere) 29 Characters Will and Company Macbeth Macduff Will and Company Radio Show Sanctimonious Kid/Joe Meddling Kidz Productions A Midsummer Night's Dream Demetrius, Bottom Theatricum Botanicum Mirror of La Mancha Cardenio Will and Company King Lear Edmund Theatricum Botanicum Passions of Shakespeare Romeo/Henry V Geffen Playhouse School for Scandal Joseph Surface Dir. -

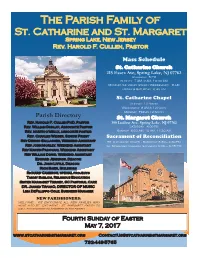

Bulletin May 7, 2017

The Parish Family of St. Catharine and St. Margaret Spring Lake, New Jersey Rev. Harold F. Cullen, Pastor Mass Schedule St. Catharine Church 215 Essex Ave, Spring Lake, NJ 07762 Saturday: 5 PM Sunday: 7 AM, 9 AM, 10:30 AM Monday- Saturday (except Wednesday): 8 AM Friday & Saturday: 6:45 AM St. Catharine Chapel Sunday: 12 Noon Wednesday: 8 AM & 12 Noon Monday - Friday 12 Noon Parish Directory St. Margaret Church Rev. Harold F. Cullen PhD, Pastor 300 Ludlow Ave. Spring Lake, NJ 07762 Rev. William Dunlap, Associate Pastor Saturday: 4.00PM Rev. martin o’reilly, associate pastor Sunday: 8:30 AM, 10 AM, 11:30 AM Rev. Charles Weiser, Senior Priest Sacrament of Reconciliation Rev Dennis Gallagher, Weekend Assistant St. Catharine Chapel, Saturday 3:30– 4:30PM Rev John Morley, Weekend Assistant St. Margaret Church, Saturday 3:00 – 3:45 PM Rev Martin Padovani, Weekend Assistant Rev William Dowd, Weekend Assistant Edward Jennings, Deacon Dr. John Little, Deacon Rich Baier, Buildings Richard Cambron, special projects Tammy Sablom, Religious Education Sister Margaret Tierney, SC Pastoral Care DR. Jarred TAfarO, DIRECTOR OF MUSIC Lisa DeFillippo Cole, Business Manager NEW PARISHIONERS: Welcome! We encourage all new families who move into St. Catharine - St. Margaret Parish to call the rectory to register in the parish. Fourth Sunday of Easter May 7, 2017 www.stcatharine-stmargaret.org [email protected] 732-449-5765 Please remember our sick: Albert Weirman, Nancy Fittin, Baby Bernadette Mariam, Bob Patrignelli, Nick Costantini, Fr. Dennis Gallagher, Scott Nokes, Helen Reh, Charles Williams, Jill Heck, Msgr. James J. -

'Nothing but the Truth': Genre, Gender and Knowledge in the US

‘Nothing but the Truth’: Genre, Gender and Knowledge in the US Television Crime Drama 2005-2010 Hannah Ellison Submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (PhD) University of East Anglia School of Film, Television and Media Studies Submitted January 2014 ©This copy of the thesis has been supplied on condition that anyone who consults it is understood to recognise that its copyright rests with the author and that no quotation from the thesis, nor any information derived therefrom, may be published without the author's prior, written consent. 2 | Page Hannah Ellison Abstract Over the five year period 2005-2010 the crime drama became one of the most produced genres on American prime-time television and also one of the most routinely ignored academically. This particular cyclical genre influx was notable for the resurgence and reformulating of the amateur sleuth; this time remerging as the gifted police consultant, a figure capable of insights that the police could not manage. I term these new shows ‘consultant procedurals’. Consequently, the genre moved away from dealing with the ills of society and instead focused on the mystery of crime. Refocusing the genre gave rise to new issues. Questions are raised about how knowledge is gained and who has the right to it. With the individual consultant spearheading criminal investigation, without official standing, the genre is re-inflected with issues around legitimacy and power. The genre also reengages with age-old questions about the role gender plays in the performance of investigation. With the aim of answering these questions one of the jobs of this thesis is to find a way of analysing genre that accounts for both its larger cyclical, shifting nature and its simultaneously rigid construction of particular conventions. -

Literariness.Org-Mareike-Jenner-Auth

Crime Files Series General Editor: Clive Bloom Since its invention in the nineteenth century, detective fiction has never been more pop- ular. In novels, short stories, films, radio, television and now in computer games, private detectives and psychopaths, prim poisoners and overworked cops, tommy gun gangsters and cocaine criminals are the very stuff of modern imagination, and their creators one mainstay of popular consciousness. Crime Files is a ground-breaking series offering scholars, students and discerning readers a comprehensive set of guides to the world of crime and detective fiction. Every aspect of crime writing, detective fiction, gangster movie, true-crime exposé, police procedural and post-colonial investigation is explored through clear and informative texts offering comprehensive coverage and theoretical sophistication. Titles include: Maurizio Ascari A COUNTER-HISTORY OF CRIME FICTION Supernatural, Gothic, Sensational Pamela Bedore DIME NOVELS AND THE ROOTS OF AMERICAN DETECTIVE FICTION Hans Bertens and Theo D’haen CONTEMPORARY AMERICAN CRIME FICTION Anita Biressi CRIME, FEAR AND THE LAW IN TRUE CRIME STORIES Clare Clarke LATE VICTORIAN CRIME FICTION IN THE SHADOWS OF SHERLOCK Paul Cobley THE AMERICAN THRILLER Generic Innovation and Social Change in the 1970s Michael Cook NARRATIVES OF ENCLOSURE IN DETECTIVE FICTION The Locked Room Mystery Michael Cook DETECTIVE FICTION AND THE GHOST STORY The Haunted Text Barry Forshaw DEATH IN A COLD CLIMATE A Guide to Scandinavian Crime Fiction Barry Forshaw BRITISH CRIME FILM Subverting -

GURPS Dungeon Fantasy 14: Psi Is Copyright © 2011 by Steve Jackson Games Incorporated

TM Written by SEAN PUNCH Illustrated by IGOR FIORENTINI, JOYCE MAUREIRA, and NEIL MELVILLE An e23 Sourcebook for GURP S® STEVE JACKSON GAMES ® Stock #37-0324 Version 1.0 – August 2011 CONTENTS I NTRODUCTION . 3 ELDER WEIRDNESS . 26 Publication History . 3 Mentalist Gift Ideas . 27 About the Author . 3 About GURPS . 3 3. PSI IN THE CAMPAIGN . 28 Psi vs. Magic . 28 1. PSIS . 4 KEEPING PSI SANE . 28 Psi Glossary . 4 Opposing Forces . 29 PSIONICS . 4 PSI IN THE DUNGEON . 30 Psionics Abilities . 5 Town . 30 Alternative Abilities . 5 Travel . 31 Things Psi Can’t Do . 7 Exploring the Dungeon . 31 Going Kojak . 8 Task Mastery . 31 But Is It Psi? . 11 Breaking and Entering . 32 Psionic Abilities Table . 11 Traps and Hazards . 32 Advantages . 14 Monsters . 32 Psi Perks . 14 Grimace and Glare . 33 Skills . 15 Combat . 33 PSIONIC DELVERS . 15 After the Battle . 34 Mentalist . 15 Loot . 34 Pside Jobs . 17 Disposing of the Spoils . 35 Going Mental . 19 Dungeon Design . 35 MENTALIST POWER -U PS . 19 Psi What? . 35 Adding and Improving Psi Abilities . 20 What’s the Use? . 36 Beyond the Dungeon . 36 4. PSIONIC THINGS . 37 Psionic Encounters Table . 37 Where there’s psi, The Horrible Truth . 38 Psionic Monsters . 41 there are Elder Things. Aloakasa as-Sharak . 41 Astral Hound . 42 Astral Thing . 42 Chaos Monk . 42 2. PSI -R ELATED GEAR . 23 Flying Squid Monster . 43 Psionic Power Items . 23 Fuzzy . 43 MUNDANE , M ORE OR LESS . 23 Neuroid . 44 Dungeoneering Gear . 23 No-Brainer . 44 Weapons and Armor . 24 Odifier . 44 Concoctions . -

LELAND SEXTON Editor !

! LELAND SEXTON Editor ! Television PROJECTS DIRECTOR STUDIO/PRODUCTION CO. LANGDON (season 1) Various NBC / Imagine Entertainment Prod: Anna Culp, Samie Kim Falvey, Brian Grazer, Ron Howard GOTHAM (seasons 2-5) Various Fox Prod: Danny Cannon, John Stephens, Bruno Heller ONCE UPON A TIME IN WONDERLAND Various ABC (season 1) Prod: Edward Kitsis, Jane Espenson, Adam Horowitz, Zack Estrin BENCHED (season 1) Various USA Prod: Michaela Watkins, John Enbom, Damon Jones, Andrea Shay WEDDING BAND (season 1, 1 episode) Peter Lauer TBS Prod: Josh Lobis, Mile Tollin, Darin Moiselle, Jon Wallace NTSF:SD:SUV PSA’s (digital series) Curtis Gwinn Funny or Die Prod: Paul Scheer, Jon Stern Assistant Editor PROJECTS DIRECTOR STUDIO/PRODUCTION CO. A MILLION LITTLE THINGS (season 3) Various ABC LIMITLESS (season 1) Various CBS HOME SWEET HELL* Anthony Burns Darko Entertainment / Vertical Entertainment Editor: Robert Hoffman OUTSIDERS (season 1) Various WGN America GOTHAM (pilot/season 1) Various Fox ONCE UPON A TIME IN WONDERLAND Various ABC (season 1) GO ON (season 1) Various NBC WEDDING BAND (season 1) Various TBS FREE AGENTS (season 1) Various NBC NTSF:SD:SUV (season 1) Various Adult Swim / Funny or Die FUNNY OR DIE PRESENTS… (season 2) Various HBO HUMAN TARGET (season 2) Various Fox CHILDRENS HOSPITAL (seasons 1-2) Various Adult Swim PARTY DOWN* (seasons 1-2) Various TBS SECRET GIRLFRIEND (season 1) Various Comedy Central HEAD CASE (season 3) Various Starz CHASING THE LIGHT (documentary) Louie Schwartzberg PBS * 1st Assistant Editor 1645 Vine Street #402, Los Angeles, CA 90028 | p 323.856.3000 | [email protected] | www.easterntalent.net !. -

GSDC Bulletin 38

ISSUE 38 Simon Baker film to boost Denmark TV star’s feature film of Tim Winton novel Funding secured through the GSDC helped to clinch a decision to produce a feature film of Tim Winton’s award-winning novel Breath in the Great Southern. Australian actor and star of The Mentalist Simon Baker visited Denmark on Friday 10 July for the announcement of the project. The production of Breath is supported by $1.5 million in State Government Royalties for Regions funding administered through the GSDC and $800,000 through ScreenWest. Mr Baker will star in and direct the film, and said he was familiar with the book. A location-scouting tour of the South West included a visit to Denmark, and Mr Baker said he and Australian producer Jamie Hilton immediately felt it was the right place to make the film. Culture and Arts Minister John Day (left), actor and director Simon Baker (centre) and Regional Development Minister Terry Redman celebrate “It was just the feel of the place and the the announcement of the Great Southern sense of community environment that rung production of the feature film Breath. out and felt special,” Mr Baker said. “We knew right there. We just looked at each “ScreenWest and the Great Southern other and we knew that we had to somehow Development Commission have worked inside this issue: try to make it work in this particular area.” closely with the film’s producers to sell the State’s attributes as a premier filming Mr Baker said he felt honoured that the destination,” Mr Day said. -

CLAREMONT News

CLAREMONT News The Events Committee has received so many requests for a repeat performance of the mind reader and superb entertainer who wowed us in 2015! We are so pleased to announce that Mark Stone, The Mentalist, has agreed to return for another performance at Claremont on Thursday night, February 21st. This won’t be a repeat of his last performance. He has an entirely new show for us! Registrations for this exciting event will begin mid-January. Seating will be limited so make your reservations early. Details will be in the Registration Book and in the February newsletter. The Claremont Women’s Club Program for Tuesday, February 12th at 6:30 p.m. will be “STIR IT UP”....”LET’S COOK!” With a presentation by Marilyn Herzog, Claremont resident and food columnist for Bethany Living Magazine. Marilyn will be sharing recipes from her eclectic culinary journey and international experiences that have influenced her relationship with food! We will be sampling three of her appetizer recipes. Be sure to sign up at the front office so we know how many to make! We will also feature a themed raffle basket. Bring your $$$ and win something special! The Events Committee wants to let Claremonters know that they have decided not to sponsor a New Year's Eve Dinner Dance on December 31, 2019. They do hope to hold a dinner dance again in 2020, but felt the event needs a year's break since attendance was lower than anticipated on NYE 2018 - a low of 68 attendees. Also, if anyone knows what happened to the twinkling lights that were part of the table decor on NYE, please notify Linda Tracy, NYE Chair. -

Comment Devenir Mentaliste

Un art de la manipulation l y a deux ans à peine, avant que la série conçue aux États-Unis par Bruno Heller ne devienne un I succès mondial, le mentalisme était uniquement connu des cercles d’initiés, des férus de magie, de communication extrasensorielle ou même de joueurs invétérés de poker, rois du bluff et de l’esbroufe. Mais voilà : avec plus de 10 millions de téléspecta- teurs en moyenne presque toutes les semaines sur les chaînes TPS Star, puis TF1 à chaque épisode, l’engoue- ment pour ces talents de compréhension ont mis au jour les techniques et autres avantages de mener les discus- sions ou la parole d’autrui dans son sens. Plutôt intéressant ! Si, dans la série The Mentalist, Patrick Jane, le sédui- sant consultant du CBI, s’amuse à dévoiler la vérité dans des affaires de meurtre, force est de constater qu’il est tout à fait possible d’utiliser ses techniques d’entour- loupe pour également s’imposer dans la vie quotidienne. Voici quelques pistes de travail, tirées de nombreux ouvrages sur le sujet, mais aussi de la fréquenta- 7 Comment devenir mentaliste tion assidue de la série. Que cela reste un loisir avant tout. Ne vous mettez pas en tête de pouvoir manipu- ler quiconque en fermant ce livre. Que nenni ! On ne cherche à montrer que, bien loin d’être de la pure magie, le mentalisme fait appel à toutes les forces de votre cerveau, de la concentration à la mémoire, en passant par votre sens de l’observation, votre discours et vos talents hypnotiques. -

“Paint It Red” Written by Eoghan Mahony Directed by Dave Barrett

“Paint It Red” Written by Eoghan Mahony Directed by Dave Barrett Episode 112 #3T7812 Warner Bros. Entertainment PRODUCTION DRAFT 4000 Warner Blvd. November 17, 2008 Burbank, CA 91522 FULL BLUE 11/18/08 PINK REVS. 11/21/08 YELLOW REVS. 11/23/08 GREEN REVS. 11/24/08 © 2008 Warner Bros. Entertainment Inc. This script is the property of Warner Bros. Entertainment Inc. No portion of this script may be performed, reproduced or used by any means, or disclosed to, quoted or published in any medium without the prior written consent of Warner Bros. Entertainment Inc. THE MENTALIST “Paint It Red” Episode #112 November 24, 2008 – Green Revisions REVISED PAGES PINK REVISIONS – 11/21/08 14, 20, 21, 30, 37, 37A YELLOW REVISIONS – 11/23/08 *(ADDENDUM – SCENE 47 DIALOGUE – INSERT AT END OF SCRIPT) GREEN REVISIONS – 11/24/08 46, 47, 49, 50, 52 TEASER FADE IN: 1 EXT. A.P. CAID OIL HQ DOWNTOWN SACRAMENTO - NIGHT (N/1) 1 The SIGN outside an imposing edifice of glass and steel proclaims it to be the headquarters of A.P. CAID PETROLEUM. 2 INT. FOYER. EXECUTIVE FLOOR. A.P. CAID OIL HQ - NIGHT 2 FRANK and KEELY are locked in a fervent kiss. He’s late 30s, turned corporate suit. She’s late 20’s, in prim but sexy receptionist kit. They make their way across the luxe foyer with a slightly furtive air, stopping at a set of heavy wooden doors. KEELY Are you sure about this? What if someone sees us? FRANK Relax, baby. I’ve got it all under control.