Visitor Motivation and Destinations with Archaeological Significance in the Philippines

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Balikbayan Plus Program Establishment Guide ( May 15, 2017 )

BALIKBAYAN PLUS PROGRAM ESTABLISHMENT GUIDE -+ ( MAY 15, 2017 ) DENTAL CLINIC HOTEL THE SPA CASTILLO-ORTHO DENTAL (Alabang, BGC, Eastwood, APO VIEW HOTEL BEAUTY & WELLNESS CLINIC ( Las Piñas City) (J.Camus St. Davao City) Greenbelt, Promenade, BEAUCHARM DERMA Shangri-la and Trinoma ) - Dr. Jose Castillo * Ms. Jasmin Acuin / FACIAL (Makati City) -Ms. Noemi Pablo-Doce* Ms. Bonadee - Basic Dental Procedures - 25% OFF Ms. Maricar Dimayuga. Ms. Paula - Ms. Cora de Guzman Castro - Orthodontics Treatment - 20% OFF - 20% OFF on hotel rooms - FREE Diamond peel on the -20% OFF on Single The Spa Wellness -Removal and Fixed Prosthesis - 20% -10% OFF on food and beverage OFF cardholder’s Ist visit Service ( on solo visit ) - Until May 31, 2018* +632.935. 6732 - 20% OFF on all major surgical and - 25% OFF on Single The Spa Wellness - Until April 07, 2018* +632.874.5355 +63.943.837.7003 non-surgical treatments Service if visiting with 2 or more companions ( PLUS 5% OFF on ENTERTAINMENT - 10% OFF on hair removal, body scrub, massage and foot treatments companion ) MANILA OCEAN PARK - Until May 31, 2018 *+632.893.0872 * -10% OFF on the New Exclusive (Manila ) ASTORIA GREENBELT +632.579.9610 Membership (Cardholder and - Ms.Mayette Ongsioco / - Ms. Mica Dumayas * companion ) Ms. Nissah Custodio Ms. Marlyn Balete BARRE 3 -Until November 14, 2017 - DISCOUNT on Attraction packages: -Room Accommodations @ 30% - (All Branches except - +632.656.5790 local 202 / 209 a) Corporate SIG -1(Oceanarium, Shark 64% OFF Greenbelt ) & Ray Dry Encounter, Symphony - 10% OFF on F&B -Ms. Noemi Pablo-Doce * SKIN DERMATOLOGY AND Evening Show, Sea Lion Show, Jellies -5% OFF on Social Functions Ms. -

BINONDO FOOD TRIP (4 Hours)

BINONDO FOOD TRIP (4 hours) Eat your way around Binondo, the Philippines’ Chinatown. Located across the Pasig River from the walled city of Intramuros, Binondo was formally established in 1594, and is believed to be the oldest Chinatown in the world. It is the center of commerce and trade for all types of businesses run by Filipino-Chinese merchants, and given the historic reach of Chinese trading in the Pacific, it has been a hub of Chinese commerce in the Philippines since before the first Spanish colonizers arrived in the Philippines in 1521. Before World War II, Binondo was the center of the banking and financial community in the Philippines, housing insurance companies, commercial banks and other financial institutions from Britain and the United States. These banks were located mostly along Escólta, which used to be called the "Wall Street of the Philippines". Binondo remains a center of commerce and trade for all types of businesses run by Filipino- Chinese merchants and is famous for its diverse offerings of Chinese cuisine. Enjoy walking around the streets of Binondo, taking in Tsinoy (Chinese-Filipino) history through various Chinese specialties from its small and cozy restaurants. Have a taste of fried Chinese Lumpia, Kuchay Empanada and Misua Guisado at Quick Snack located along Carvajal Street; Kiampong Rice and Peanut Balls at Café Mezzanine; Kuchay Dumplings at Dong Bei Dumplings and the growing famous Beef Kan Pan of Lan Zhou La Mien. References: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Binondo,_Manila TIME ITINERARY 0800H Pick-up -

Land Use Planning in Metro Manila and the Urban Fringe: Implications on the Land and Real Estate Market Marife Magno-Ballesteros DISCUSSION PAPER SERIES NO

Philippine Institute for Development Studies Land Use Planning in Metro Manila and the Urban Fringe: Implications on the Land and Real Estate Market Marife Magno-Ballesteros DISCUSSION PAPER SERIES NO. 2000-20 The PIDS Discussion Paper Series constitutes studies that are preliminary and subject to further revisions. They are be- ing circulated in a limited number of cop- ies only for purposes of soliciting com- ments and suggestions for further refine- ments. The studies under the Series are unedited and unreviewed. The views and opinions expressed are those of the author(s) and do not neces- sarily reflect those of the Institute. Not for quotation without permission from the author(s) and the Institute. June 2000 For comments, suggestions or further inquiries please contact: The Research Information Staff, Philippine Institute for Development Studies 3rd Floor, NEDA sa Makati Building, 106 Amorsolo Street, Legaspi Village, Makati City, Philippines Tel Nos: 8924059 and 8935705; Fax No: 8939589; E-mail: [email protected] Or visit our website at http://www.pids.gov.ph TABLE of CONTENTS Page 1. Introduction 1 2. The Urban Landscape: Metro Manila and its 2 Peripheral Areas The Physical Environment 2 Pattern of Urban Settlement 4 Pattern of Land Ownership 9 3. The Institutional Environment: Urban Management and Land Use Planning 11 The Historical Precedents 11 Government Efforts Toward Comprehensive 14 Urban Planning The Development Control Process: 17 Centralization vs. Decentralization 4. Institutional Arrangements: 28 Procedural Short-cuts and Relational Contracting Sources of Transaction Costs in the Urban 28 Real Estate Market Grease/Speed Money 33 Procedural Short-cuts 36 5. -

DINING MERCHANT PARTICIPATING BRANCHE/S OFFER Wooden Horse Steakhouse G/F Molito Complex, Madrigal Ave., Cor Alabang Zapote Road

DINING MERCHANT PARTICIPATING BRANCHE/S OFFER G/F Molito Complex, Madrigal Ave., cor Alabang Zapote Road Wooden Horse Steakhouse 10% OFF on total bill Muntinlupa City SM Megamall - 2/F Mega Atruim, Julia Vargas Ave., Wack Wack 15% OFF on total bill Kichitora Mandaluyong BCG - 3/F BGC Central Sqaure, BGC Taguig City Greenbelt 3 - 3/F Greenbelt 3, Makati City 15% OFF on total bill Motorino BGC - G/F Netlima Bldg. BGC Taguig City Tappella Greenbelt 5 - G/4 Greenbelt 5 Ayala Center Makati City 10% OFF on total bill La Cabrera Glorieta Complex - 6750 Building Glorieta Complex Makati City 15% OFF on total bill Nikkei No. 111 Frabelle Bldg. Rada Street Legaspi Village Makati City 15% OFF on total bill Alimall – Araneta Centre Cubao Quezon City Alabang – Festival Mall Alabang Antipolo – Sumulong Hills Antipolo Antipolo – Robinsons Place Antipolo Baguio – SM City Baguio Cebu – SM City Cebu Congressional – Barrington Place, Congressional Ave. QC Katipunan – Katipunan Ave, Loyola Heights QC Manila – SM City Manila The Old Spaghetti House 10% OFF on total bill Market! Market! – Bonifacio Global City, Taguig Marikina – SM City Marikina – Midtown – Robinsons Place Ermita Midtown MOA – SM Mall of Asia Otis – Robinsons Place Otis Pioneer – Robinsons Place Forum SM The Block – SM City North Edsa The Block Sta Rosa – Solenad 3, Sta Rosa Laguna Valero – Paseo De Roxas Valero Street Makati Antipolo – Robinsons Place Antipolo MOA – SM City Mall of Asia Market! Market! – Bonifacio Global City, Taguig The Shrimp Shack 10% OFF on total bill Midtown – Robinsons Place Ermita Midtown SM The Block – SM North Edsa The Block Pioneer – Robinsons Place Forum Pioneer Greenhills San Juan Greenbelt 5 Diliman Torch Trinoma Mall 10% OFF on total bill BGC Alabang Olympia Venice Grand Canal Mall, McKinley Hill, Taguig Rice & Dough 10% OFF on total bill Eastwood Mall Ayala Fairview Terraces Gateway Mall Robinsons Galleria Rockwell SM City Marikina SM City North EDSA- The Block Burgoo SM Mall of Asia 10% OFF on total bill SM South Mall Solenad 3, Nuvali, Sta. -

PHILIPPINES Manila GLT Site Profile

PHILIPPINES Manila GLT Site Profile AZUSA PACIFIC UNIVERSITY GLOBAL LEARNING TERM 626.857.2753 | www.apu.edu/glt 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION TO MANILA ................................................... 3 GENERAL INFORMATION ........................................................ 5 CLIMATE AND GEOGRAPHY .................................................... 5 DIET ............................................................................................ 5 MONEY ........................................................................................ 6 TRANSPORTATION ................................................................... 7 GETTING THERE ....................................................................... 7 VISA ............................................................................................. 8 IMMUNIZATIONS ...................................................................... 9 LANGUAGE LEARNING ............................................................. 9 HOST FAMILY .......................................................................... 10 EXCURSIONS ............................................................................ 10 VISITORS .................................................................................. 10 ACCOMODATIONS ................................................................... 11 SITE FACILITATOR- GLT PHILIPPINES ................................ 11 RESOURCES ............................................................................... 13 NOTE: Information is subject to -

Jcb Unique Dining Experience Merchants

JCB UNIQUE DINING EXPERIENCE MERCHANTS 7107 Culture + Cuisine Restaurant • G/F, Treston Bldg., BGC Alba Restaurante Espaǹol • Bel-Air, Makati City • Tomas Morato Quezon City • Westgate Center,Muntinlupa City • Prism Plaza, TwoEcom Center Building Mall of Asia Complex, Pasay City • Estancia Mall Capitol Commons, Pasig City Alchemy - Bistro • 4893 Durban St. Poblacion Makati Bari Uma Ramen • Ground Floor Serendra, Bonifacio High Street, BGC • Ayala Center Cebu Burgoo • The Block, North Edsa • SM City Marikina • The District Imus • Solenad 3, Nuvali • Robinsons Galleria • SM Mall of Asia • Gateway Mall • SM Southmall • Fairview Terraces • Vista Mall, Taguig Butamaru • West Gate Center, Alabang, Muntinlupa City • Technopoint Bldg, Pasig Chairman Wang's • Molito Lifestyle Bldg, Alabang Chotto Matte • Net Park, 5th Avenue, Bonifacio Global City, Taguig City Gumbo • SM Mall of Asia • Mega Atrium, Megamall • Robinsons Magnolia Hatsu Hana Tei • Herald Suites, Don Chino Roces Avenue, Makati City Ikomai & Tochi • ACI Group Building Makati City Izakaya Sensu • Net Park Building Bonifacio, Global City Kichitora • Bonifacio Highstreet Central, Bonifacio Global City • SM Megamall La Cabrera • Ayala Business Center, 6750 Ayala Avenue Mireio • 1 Raffles Drive Makati Avenue, Makati City Motto Motto • Ground Floor, Serendra, Bonifacio Global City, Taguig City Txanton • Alegria Alta Building,Makati City Wooden Horse Steakhouse • Molito Complex Alabang Yanagi • Midas Hotel Roxas Blvd, Pasay Yoshinoya • Glorietta Mall • SMCity Cebu North • Robinsons, Cybergate -

Vigía: the Network of Lookout Points in Spanish Guam

Vigía: The Network of Lookout Points in Spanish Guam Carlos Madrid Richard Flores Taitano Micronesian Area Research Center There are indications of the existence of a network of lookout points around Guam during the 18th and 19th centuries. This is suggested by passing references and few explicit allusions in Spanish colonial records such as early 19th Century military reports. In an attempt to identify the sites where those lookout points might have been located, this paper surveys some of those references and matches them with existing toponymy. It is hoped that the results will be of some help to archaeologists, historic preservation staff, or anyone interested in the history of Guam and Micronesia. While the need of using historic records is instrumental for the abovementioned purposes of this paper, focus will be given to the Chamorro place name Bijia. Historical evolution of toponymy, an area of study in need of attention, offers clues about the use or significance that a given location had in the past. The word Vigía today means “sentinel” in Spanish - the person who is responsible for surveying an area and warn of possible dangers. But its first dictionary definition is still "high tower elevated on the horizon, to register and give notice of what is discovered". Vigía also means an "eminence or height from which a significant area of land or sea can be seen".1 Holding on to the latter definition, it is noticeable that in the Hispanic world, in large coastal territories that were subjected to frequent attacks from the sea, the place name Vigía is relatively common. -

Cities Development Initiative for Asia P R O J E C T O V E R V I E W

Cities Development Initiative for Asia P R O J E C T O V E R V I E W Country: P H I L I P P I N E S Status: Key Sector(s): COMPLETED FLOOD AND DRAINAGE MANAGEMENT City: VALENZUELA Application approved: 20/JAN/2014 P R O P O N E N T S Geography and Population Valenzuela City Government Mayor Rex Gatchalian Area: 44.59 km2 City Hall, MacArthur Highway, City Mayor Barangay Karuhatan, Valenzuela City, City Government of Valenzuela Population: 598,968 Metropolitan Manila 1400 The city of Valenzuela is located 14km north of Phone: (+63) 2 352 1000 Phone: (+63) 291 3069 Manila, the capital city of Website: www.valenzuela.gov.ph the Philippines. It is one of the 16 highly urbanized Central State Partner Other Partners cities of Metropolitant National Economic Development DPWH, Maynilad Manila. Due to its strategic Authority (NEDA) location at the northern K E Y C I T Y D E V E L O P M E N T I S S U E S most part of Metro Manila, and the migration of The overall city's development plans focus on the following areas: people, Valenzuela has Valenzuela is located in an area that has 16% frequency of tropical cyclones grown into a major also, a third of the city, particularly the western side is composed of swampy economic and industrial areas that are not only one to five meters above the sea level; this greatly center. makes the city particularly the improverished areas susceptible to flooding. -

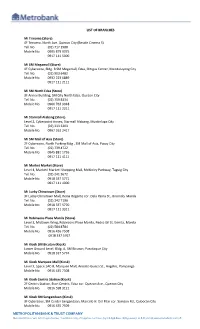

Metropolitan Bank & Trust Company List

LIST OF BRANCHES Mi Trinoma (Store) 4F Trinoma, North Ave. Quezon City (Beside Cinema 5) Tel. No. (02) 717 1980 Mobile No. 0995 879 9075 0917 111 5000 Mi SM Megamall (Store) 4F Cyberzone, Bldg. B SM Megamall, Edsa, Ortigas Center, Mandaluyong City Tel. No. (02) 903 6482 Mobile No. 0932 223 6889 0917 111 2111 Mi SM North Edsa (Store) 3F Annex Building, SM City North Edsa, Quezon City Tel. No. (02) 759 8334 Mobile No. 0966 763 9048 0917 111 2211 Mi Starmall Alabang (Store) Level 2, Cyberpoint Annex, Starmall Alabang, Muntinlupa City Tel. No. (02) 333 3203 Mobile No. 0967 262 2417 Mi SM Mall of Asia (Store) 2F Cyberzone, North Parking Bldg., SM Mall of Asia, Pasay City Tel. No. (02) 739 4722 Mobile No. 0945 881 1726 0917 111 4111 Mi Market Market (Store) Level 4, Market! Market! Shopping Mall, McKinley Parkway, Taguig City Tel. No. (02) 241 3672 Mobile No. 0918 337 5771 0917 111 4000 Mi Lucky Chinatown (Store) 3F Lucky Chinatown Mall, Reina Regente cor. Dela Reina St., Binondo, Manila Tel. No. (02) 242 7190 Mobile No. 0918 337 5770 0917 111 3311 Mi Robinsons Place Manila (Store) Level 3, Midtown Wing, Robinsons Place Manila, Pedro Gil St. Ermita, Manila Tel. No. (02) 584 8784 Mobile No. 0916 436 7508 0918 337 5767 Mi Kiosk SM Bicutan (Kiosk) Lower Ground Level, Bldg. A, SM Bicutan, Parañaque City Mobile No. 0918 337 5774 Mi Kiosk Marquee Mall (Kiosk) Level 3, Space 1AC-8, Marquee Mall, Aniceto Gueco St., Angeles, Pampanga Mobile No. 0916 435 7508 Mi Kiosk Centris Station (Kiosk) 2F Centris Station, Eton Centris, Edsa cor. -

Tour Descriptions Tour: Combination City of Old

TOUR DESCRIPTIONS TOUR: COMBINATION CITY OF OLD & NEW MANILA DURATION: FULL DAY (8 HOURS) This tour is an orientation tour that features the old and new Manila. This tour is designed to let you have a feel of Manila’s old lifestyle and to let you take a peak on Manila’s ultra - modern metropolises. A tour that will have you traversed from Manila’s historic past to the present modern and emerging urban centers. Come! Experience the FUN and friendliness in one of the most hospitable cities in Asia. In the first part of the tour, visit Rizal Park and Monument-One of Manila’s most important landmark and pay homage to our national hero Dr. Jose Rizal. Proceed to Intramuros - walled city of Manila, where the seat of government during the Spanish Colonial Period is situated. Visit Fort Santiago - oldest and most important fortification during the Spanish rule, Manila Cathedral - seat of the archdiocese of Manila, San Agustin Church - Old Catholic Church in the Philippines and UNESCO world heritage site and Casa Manila-museum that features Spanish era ilustrado house. Lunch at local restaurant. After lunch we proceed to the second part of the tour. Visit Manila American Cemetery, pay homage to WWII heroes, pass by Forbes Park - Manila’s millionaires’ row. And proceed on a driving tour of Bonifacio Global City - Manila’s emerging ultra-modern urban center. We then proceed to Ayala Malls in Makati City for free time shopping. Rizal Park and Monument Fort Santiago, Manila TOUR: SCENIC TAGAYTAY RIDGE DURATION: FULL DAY (8-10 HOURS) Only a few hours’ drive from Manila is the refreshing wisp of a city and capture the panoramic & most splendid views of the Taal Volcano – the world’s smallest, while the cool breeze offer a brief escape from the heat of Manila – all from the picturesque city of Tagaytay. -

MANILA BAY AREA SITUATION ATLAS December 2018

Republic of the Philippines National Economic and Development Authority Manila Bay Sustainable Development Master Plan MANILA BAY AREA SITUATION ATLAS December 2018 MANILA BAY AREA SITUATION ATLAS December 2018 i Table of Contents Preface, v Administrative and Institutional Systems, 78 Introduction, 1 Administrative Boundaries, 79 Natural Resources Systems, 6 Stakeholders Profile, 85 Climate, 7 Institutional Setup, 87 Topography, 11 Public-Private Partnership, 89 Geology, 13 Budget and Financing, 91 Pedology, 15 Policy and Legal Frameworks, 94 Hydrology, 17 National Legal Framework, 95 Oceanography, 19 Mandamus Agencies, 105 Land Cover, 21 Infrastructure, 110 Hazard Prone Areas, 23 Transport, 111 Ecosystems, 29 Energy, 115 Socio-Economic Systems, 36 Water Supply, 119 Population and Demography, 37 Sanitation and Sewerage, 121 Settlements, 45 Land Reclamation, 123 Waste, 47 Shoreline Protection, 125 Economics, 51 State of Manila Bay, 128 Livelihood and Income, 55 Water Quality Degradation, 129 Education and Health, 57 Air Quality, 133 Culture and Heritage, 61 Habitat Degradation, 135 Resource Use and Conservation, 64 Biodiversity Loss, 137 Agriculture and Livestock, 65 Vulnerability and Risk, 139 Aquaculture and Fisheries, 67 References, 146 Tourism, 73 Ports and Shipping, 75 ii Acronyms ADB Asian Development Bank ISF Informal Settlers NSSMP National Sewerage and Septage Management Program AHLP Affordable Housing Loan Program IUCN International Union for Conservation of Nature NSWMC National Solid Waste Management Commission AQI Air Quality Index JICA Japan International Cooperation Agency OCL Omnibus Commitment Line ASEAN Association of Southeast Nations KWFR Kaliwa Watershed Forest Reserve OECD Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development BSWM Bureau of Soils and Water Management LGU Local Government Unit OIDCI Orient Integrated Development Consultants, Inc. -

Looking Beyond the Walls

Looking Beyond the Walls It was a sunny morning when Jose Estrella decided to take a walk by the Maestranza plaza in Intramuros, Manila City. Estrella was the administrator of the Intramuros Administration (IA), an organization attached to the Department of Tourism (DOT) of the Philippines. He was walking by the plaza because he wanted to check on the current state of Maestranza in preparation for several meetings he had lined up for the week. A concert had recently been held at the Maestranza plaza, and an exhibit had been held a few weeks ago. A civic organization was currently eying Maestranza as the venue for its annual meeting six months from now. A few years back, however, this portion of Intramuros where the Pasig River can be seen had an unwelcoming sewage-like smell that dominated a person’s senses. It consequently was not a pleasurable place for a walk. There were informal settlers who had made their homes and lives right in the middle of the street, blocking important historical markers and obstructing the view of Pasig River as well as portions of the historic walls of Manila. A few meters from Maestranza were ruins of what used to be the Central Bank of the Philippines. No matter how historic and rich in potential this area was, it was not a prime tourism destination. As the administrator of Intramuros, Estrella was proud that in the two years’ time since he had assumed his position, the plaza had a facelift, allowing it to become a viable venue for different events and an open space good for a morning or afternoon stroll.