Purcell Manuscripts the Principal Musical Sources

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Daniel Purcell the Judgment of Paris

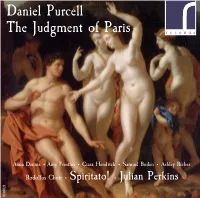

Daniel Purcell The Judgment of Paris Anna Dennis • Amy Freston • Ciara Hendrick • Samuel Boden • Ashley Riches Rodolfus Choir • Spiritato! • Julian Perkins RES10128 Daniel Purcell (c.1664-1717) 1. Symphony [5:40] The Judgment of Paris 2. Mercury: From High Olympus and the Realms Above [4:26] 3. Paris: Symphony for Hoboys to Paris [2:31] 4. Paris: Wherefore dost thou seek [1:26] Venus – Goddess of Love Anna Dennis 5. Mercury: Symphony for Violins (This Radiant fruit behold) [2:12] Amy Freston Pallas – Goddess of War 6. Symphony for Paris [1:46] Ciara Hendricks Juno – Goddess of Marriage Samuel Boden Paris – a shepherd 7. Paris: O Ravishing Delight – Help me Hermes [5:33] Ashley Riches Mercury – Messenger of the Gods 8. Mercury: Symphony for Violins (Fear not Mortal) [2:39] Rodolfus Choir 9. Mercury, Paris & Chorus: Happy thou of Human Race [1:36] Spiritato! 10. Symphony for Juno – Saturnia, Wife of Thundering Jove [2:14] Julian Perkins director 11. Trumpet Sonata for Pallas [2:45] 12. Pallas: This way Mortal, bend thy Eyes [1:49] 13. Venus: Symphony of Fluts for Venus [4:12] 14. Venus, Pallas & Juno: Hither turn thee gentle Swain [1:09] 15. Symphony of all [1:38] 16. Paris: Distracted I turn [1:51] 17. Juno: Symphony for Violins for Juno [1:40] (Let Ambition fire thy Mind) 18. Juno: Let not Toyls of Empire fright [2:17] 19. Chorus: Let Ambition fire thy Mind [0:49] 20. Pallas: Awake, awake! [1:51] 21. Trumpet Flourish – Hark! Hark! The Glorious Voice of War [2:32] 22. -

November 15, 1959 776Th Concert

NATIONAL GALLERY ORCHESTRA Richard Bales, Conductor Violins: Cellos: Mark Ellsworth Ana Drittelle Helmut Braunlich Helen Coffman Henri Sokolov Basses: Raul Da Costa Charles Hamer Dino Cortese Joseph Widens Michael Serber Oboes: THE A. W. MELLON CONCERTS Joel Berman Beth Sears Elinore Tramontana Donald Hefner Eugene Dreyer Bassoon: Isadore Glazer Dorothy Erler Maurice Myers Collin Layton Trumpets: National Gallery of Art Samuel Feldman Richard Smith George Gaul Charles Gallagher, Jr. Washington, D. C. Carmen Parlante Violas: Frank Perricone Leon Feldman T ympani: Barbara Grzesnikowski Walter Howe 776th Concert CHURCH OF THE REFORMATION CANTATA CHOIR Jule Zabawa, Minister of Music Sopranos Altos Tenors Basses Marilyn Krummel Mary Lou Alexander Otto Kundert Harald Strand Eleanor Pressly Mary Forsythe Stephen Beaudry Gerard Siems Handel Bicentennial Program Julia Fromm Blosson Athey Arleigh Green Gilbert Mitchell Julia Green Estella Hyssong Robert Ernst Donald Robinson Patricia Foote Virginia Jones Joseph Agee Richard Foote Dorothy Richardson Marion Kahlert Leslie Polk Glenn Dabbs Ruth Siems Betty Ann Dabbs John Nordberg Edward Bachschmid Sunday Evening Beatrice Shelton Marilyn Smith Charles Kalb Fred Bloch Virginia Mitchell Jane Bennett Donald Krummel Rudolf Michel November 15, 1959 Marion Bradley Barbara Bachschmid John Kjerland John Ramseth Dorothy Moser Jeanne Beaudry Hilman Lund Kay Sisson Mary Bentley Gerald Wolford Norma Grimes Lydia Bloch Austin Vicht Lydia Nordberg Phyllis Wilkes Marion Kalb Ruth Schallert Betty Schulz Lucy Grant AT EIGHT O’CLOCK Hazel Rust Beverly Isaacson Christine Agee Moreen Robinson Bertha Rothe Vivian Schrader Clara Rampendahl lone Holmes IN THE EAST GARDEN COURT Diane Diehl NATIONAL GALLERY ORCHESTRA GEORGE FREDERIC HANDEL CHURCH OF THE REFORMATION CANTATA CHOIR (1685-1759) Concerto Grosso in A Major, Opus 6, No. -

Barockkonzert FR 03.06.2016 SA 04.06.2016 Jan Willem De Vriend Dirigent Iestyn Davies Countertenor

B4 Barockkonzert FR 03.06.2016 SA 04.06.2016 Jan Willem de Vriend Dirigent Iestyn Davies Countertenor 14780_rph1516_b4_16s_PRO_K1.indd 1 10.05.16 15:54 RING BAROCK B4 PAUSE FR 03.06.2016 18 UHR Let Thy Hand Be Strengthened HWV 259 HERRENHAUSEN NDR Radiophilharmonie Coronation Anthem Nr. 2 GALERIEGEBÄUDE Knabenchor Hannover (Erstaufführung 11. Oktober 1727) (Jörg Breiding, Einstudierung) SA 04.06.2016 Jan Willem de Vriend Dirigent 16 UHR Iestyn Davies Countertenor „Cara sposa“ aus „Rinaldo“ HWV 7a ST.-GEORGEN-KIRCHE (Erstaufführung 24. Februar 1711) WISMAR Georg Friedrich Händel | 1685 – 1759 „Venti turbini“ aus „Rinaldo“ HWV 7a (Erstaufführung 24. Februar 1711) Zadok The Priest HWV 258 Coronation Anthem Nr. 1 The King Shall Rejoice HWV 260 (Erstaufführung 11. Oktober 1727) Coronation Anthem Nr. 3 (Erstaufführung 11. Oktober 1727) „Oh Lord, whose mercies numberless“ aus „Saul“ HWV 53 SPIELDAUER: CA. 40 MINUTEN (1738, Erstaufführung 16. Januar 1739) „Despair no more shall wound me“ aus „Semele“ HWV 58 (1743, Erstaufführung 10. Februar 1744) My Heart Is Inditing HWV 261 Coronation Anthem Nr. 4 (Erstaufführung 11. Oktober 1727) SPIELDAUER: CA. 30 MINUTEN Das Konzert wird aufgezeichnet und am 10. Juli 2016 um 11 Uhr auf NDR Kultur gesendet. (Hannover: 98,7 MHz) 14780_rph1516_b4_16s_PRO_K1.indd 2 10.05.16 15:54 14780_rph1516_b4_16s_PRO_K1.indd 3 10.05.16 15:54 Biografie In Kürze Die Dinge verliefen günstig für Georg Friedrich Händel im Jahre 1727. Seit 1712 in London lebend, war er 1723 zum „Composer of Musick for his Majesty’s Chappel Royal“ ernannt worden. Im Februar 1727 nun wurde seinem Antrag auf Einbürgerung stattgegeben, und so wurde aus dem ehemaligen „Caro Sassone“, dem italophilen Sachsen, ein wahrer englischer Komponist. -

Music for Mercer's: an Analysis of Eighteenth-Century Manuscript

Music for Mercer’s: an analysis of eighteenth-century manuscript sources O'Hanlon, T. (2010). Music for Mercer’s: an analysis of eighteenth-century manuscript sources. The Musicology Review, (6), 27-56. https://www.themusicologyreview.com/previous-issues/issue-6-edited-by-majella-boland- and-jennifer-mccay/ Published in: The Musicology Review Document Version: Peer reviewed version Queen's University Belfast - Research Portal: Link to publication record in Queen's University Belfast Research Portal Publisher rights Copyright UCD 2010. General rights Copyright for the publications made accessible via the Queen's University Belfast Research Portal is retained by the author(s) and / or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing these publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Take down policy The Research Portal is Queen's institutional repository that provides access to Queen's research output. Every effort has been made to ensure that content in the Research Portal does not infringe any person's rights, or applicable UK laws. If you discover content in the Research Portal that you believe breaches copyright or violates any law, please contact [email protected]. Download date:03. Oct. 2021 Abstract Music for Mercer’s: an analysis of eighteenth-century manuscript sources The Mercer’s Hospital music collection includes fifty vocal and instrumental manuscript part-books for works by Handel, Greene, Boyce, Purcell, Humfrey and Corelli. Selected works from this collection were performed at the hospital’s annual benefit concerts, the first of which took place on 8 April 1736. Preliminary examination of the part-books raises several questions surrounding the lineage and dating of these sources. -

The Music of Three Dublin Musical Societies of the Late Eighteenth And

t 0 - ^r\b 3 NUI MAYNOOTH Ollscoil na hÉireann Mà Nuad The music of three Dublin musical societies of the late eighteenth and nineteenth centuries: The Anacreontic Society, The Antient Concerts Society and The Sons of Handel. A descriptive catalogue. Catherine Mary Pia Kiely-Ferris Volume III of IV: The Sons of Handel Catalogue and The Antient Concerts Society Main Catalogue Thesis submitted to National University of Ireland, Maynooth for the Degree of Master of Literature in Music. Mead of Department: Professor Gerard Gillen Music Department National University of Ireland, Maynooth Maynooth Co. Kildare Supervisor: Dr Barra Boydell Music Department National University of Ireland, Maynooth Maynooth Co. Kildare July 2005 TABLE OF CONTENTS Volume III of IV 1: Cataloguing procedures and user guide.............................................1 2: The Sons of Handel Catalogue......................................................... 13 3. The Antient Concerts Society Main Catalogue...............................17 Accompanying photographs to Sons of Handel Catalogue: CD 2 Accompanying photographs to The Antient Concerts Society Main Catalogues CD 3a & 4a CATALOGUING PROCEDURES AND USER GUIDE: THE SONS OF HANDEL AND THE ANTIENT CONCERTS SOCIETY This catalogue was produced to fulfill the requirements of the Royal Irish Academy of Music library and to provide researchers with a descriptive and detailed catalogue of each score and manuscript associated with the Sons of Handel and The Antient Concerts Society. For one to be able to utilize the catalogue, one must first understand the methods of cataloguing and the format that the catalogue takes. The format for this catalogue is derived from three sources: the Royal Irish Academy of Music library’s current cataloguing standards, Anne Dempsey’s catalogue of the Armagh Cathedral Collection1, and the Anglo-American Cataloguing Rules. -

19Th Century Writing Activity: Pen &

Lesson Plan: #NoyesArtatHome 19th Century Writing Activity: Pen & Ink Activity based on letters on display in the Noyes Museum’s Estell Empire Exhibition For ages 12 & up Experience with cursive* writing not necessary Assistance from an adult would be helpful. Overview: Round Hand Script: This was the dominant cursive* writing style among 19th century writing “masters,” whose An account book from John Estell’s general store models were engraved on metal. Letters Circa 1836 – 1837 sloped to the right, and thick lines were © Collection of Stockton University produced on the downstrokes using a flexible, straight-edged (not pointed) pen nib (tip). Thin lines were made by using the corner of the nib. Round hand included decorative swirls referred to as “command of hand.” Copperplate: This type of writing was made with a flexible, pointed metal pen. Copperplate script differs from round hand in the gradual swelling of the broad strokes on curved forms and the narrowness of the backstrokes of b, e, and o. Definitions from Britannica.com: https://www.britannica.com/topic/black-letter Project Description: This lesson provides a brief overview of handwriting in the 19th century and a hands-on writing activity. First, paint with a teabag to make “old” looking paper. To write, use a quill** pen with black ink or watered-down paint, or a marker. Try to read and copy the example of 19th century writing. Can you write your own name, or a whole letter to a friend? Supplies: 8.5 x 11” piece of paper A tea bag; preferably a darker tea such as black tea (Lipton, Red Rose) A watercolor brush Your choice of: a quill** pen and black ink, watered-down black paint with a fine-tipped brush, or a black marker (for example: Crayola – “broad line” or Sharpie – “fine point,” the newer, the better) *Cursive writing is a style of writing in which all of the letters in a word are connected. -

LCOM182 Lent & Eastertide

LITURGICAL CHORAL AND ORGAN MUSIC Lent, Holy Week, and Eastertide 2018 GRACE CATHEDRAL 2 LITURGICAL CHORAL AND ORGAN MUSIC GRACE CATHEDRAL SAN FRANCISCO LENT, HOLY WEEK, AND EASTERTIDE 2018 11 MARCH 11AM THE HOLY EUCHARIST • CATHEDRAL CHOIR OF MEN AND BOYS LÆTARE Introit: Psalm 32:1-6 – Samuel Wesley Service: Collegium Regale – Herbert Howells Psalm 107 – Thomas Attwood Walmisley O pray for the peace of Jerusalem - Howells Drop, drop, slow tears – Robert Graham Hymns: 686, 489, 473 3PM CHORAL EVENSONG • CATHEDRAL CAMERATA Responses: Benjamin Bachmann Psalm 107 – Lawrence Thain Canticles: Evening Service in A – Herbert Sumsion Anthem: God so loved the world – John Stainer Hymns: 577, 160 15 MARCH 5:15PM CHORAL EVENSONG • CATHEDRAL CHOIR OF MEN AND BOYS Responses: Thomas Tomkins Psalm 126 – George M. Garrett Canticles: Third Service – Philip Moore Anthem: Salvator mundi – John Blow Hymns: 678, 474 18 MARCH 11AM THE HOLY EUCHARIST • CATHEDRAL CHOIR OF MEN AND BOYS LENT 5 Introit: Psalm 126 – George M. Garrett Service: Missa Brevis – Giovanni Pierluigi da Palestrina Psalm 51 – T. Tertius Noble Anthem: Salvator mundi – John Blow Motet: The crown of roses – Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky Hymns: 471, 443, 439 3PM CHORAL EVENSONG • CATHEDRAL CAMERATA Responses: Thomas Tomkins Psalm 51 – Jeffrey Smith Canticles: Short Service – Orlando Gibbons Anthem: Aus tiefer Not – Felix Mendelssohn Hymns: 141, 151 3 22 MARCH 5:15PM CHORAL EVENSONG • CATHEDRAL CHOIR OF MEN AND BOYS Responses: William Byrd Psalm 103 – H. Walford Davies Canticles: Fauxbourdons – Thomas -

Dr. John Blow (1648-1708) Author(S): F

Dr. John Blow (1648-1708) Author(s): F. G. E. Source: The Musical Times and Singing Class Circular, Vol. 43, No. 708 (Feb. 1, 1902), pp. 81-88 Published by: Musical Times Publications Ltd. Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/3369577 Accessed: 05-12-2015 16:35 UTC Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/page/ info/about/policies/terms.jsp JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Musical Times Publications Ltd. is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to The Musical Times and Singing Class Circular. http://www.jstor.org This content downloaded from 137.189.170.231 on Sat, 05 Dec 2015 16:35:56 UTC All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions THE MUSICAL TIMES.-FEBRUARY I, 1902. 81 THE MUSICAL composerof some fineanthems and known to TIMES everybodyas the authorof the ' Grand chant,'- AND SINGING-CLASS CIRCULAR. and William Turner. These three boys FEBRUARY I, 1902. collaboratedin the productionof an anthem, therebycalled the Club Anthem,a settingof the words ' I will always give thanks,'each young gentlemanbeing responsible for one of its three DR. JOHN BLOW movements. The origin of this anthem is variouslystated; but the juvenile joint pro- (1648-I7O8). -

Quill Pen and Nut Ink

Children of Early Appalachia Quill Pen and Nut Ink Grades 3 and up Early writing tools were made from materials people could find or easily make themselves. Children used a slate with chalk and stone to write lessons at schools. They also practiced drawing and writing with a stick in dirt. Penny pencils for slates were available at general stores. Paper was purchased at stores too. Before the invention of pencils and pens, children used carved twigs or goose-quill pens made by the teacher. Ink was made at home from various ingredients (berries, nuts, roots, and soot) and brought to school. Good penmanship was highly valued but difficult to attain. Objective: Students will make pen and ink from natural materials and try writing with these old- fashioned tools. Materials: Pen: feathers, sharp scissors or a pen knife (Peacock or pheasant feathers make wonderful pens, but any large feather from a goose or turkey works well too.) Ink: 10 walnut shells, water, vinegar, salt, hammer, old cloth, saucepan, small jar with lid, strainer. (After using the homemade ink, students make like to continue practicing writing with the quill, so you may want to provide a bottle of manufactured ink for further quill writings.) Plan: Pen: Cut off the end of the feather at a slant. Then cut a narrow slit at the point of the pen. Ink: 1. Crush the shells in cloth with a hammer. 2. Put shells in saucepan with 1 cup of water. Bring to a boil, and then simmer for 45 minutes or until dark brown. -

Pitt Artist Pen Calligraphy !

Pitt Artist Pen Calligraphy ! A new forest project in Colombia secures the livelihoods of small farmers and the Faber-Castell stands for quality wood supply for Faber-Castell – a unique environment protection programme, Founded in 1761, Faber-Castell is one of the world’s oldest industrial companies and is now in certified by the UN. the hands of the eighth generation of the same family. Today it is represented in more than With a socially exemplary and sustainable reforestation project in Colombia, Faber-Castell con- 120 countries. Faber-Castell has its own production sites in nine countries and sales companies tinues to reinforce its leading role as a climate-neutral company. On almost 2,000 hectares of in 23 countries worldwide. Faber-Castell is the world’s leading manufacturer of wood-cased pencils, grassland along the Rio Magdalena in Colombia, small farmers are planting tree seedlings for fu- producing over 2000 million black-lead and colour pencils per year. Its leading position on the ture pencil production. The fast-growing forests not only provide excellent erosion protection for international market is due to its traditional commitment to the highest quality and also the large this region plagued by overgrazing and flooding, they are also a reliable source of income for the number of product innovations. farmers living in modest circumstances, who are paid for forest maintenance and benefit from the Its Art & Graphic range allows Faber-Castell to enjoy a great reputation among artists and hobby proceeds from the timber. The environmental project was one of the first in the world to be certi- painters. -

The Origins of the Musical Staff

The Origins of the Musical Staff John Haines For Michel Huglo, master and friend Who can blame music historians for frequently claiming that Guido of Arezzo invented the musical staff? Given the medieval period’s unma- nageable length, it must often be reduced to as streamlined a shape as possible, with some select significant heroes along the way to push ahead the plot of musical progress: Gregory invented chant; the trouba- dours, vernacular song; Leoninus and Perotinus, polyphony; Franco of Cologne, measured notation. And Guido invented the staff. To be sure, not all historians put it quite this way. Some, such as Richard Hoppin, write more cautiously that “the completion of the four-line staff ...is generally credited to Guido d’Arezzo,”1 or, in the words of the New Grove Dictionary of Music, that Guido “is remembered today for his development of a system of precise pitch notation through lines and spaces.”2 Such occasional caution aside, however, the legend of Guido as inventor of the staff abides and pervades. In his Notation of Polyphonic Music, Willi Apel writes of “the staff, that ingenious invention of Guido of Arezzo.”3 As Claude Palisca puts it in his biography of Guido, it was that medieval Italian music writer’s prologue to his antiphoner around 1030 that contained one of the “brilliant proposals that launched the Guido legend, the device of staff notation.”4 “Guido’s introduction of a system of four lines and four spaces” is, in Paul Henry Lang’s widely read history, an “achievement” deemed “one of the most significant in -

Restoration Keyboard Music

Restoration Keyboard Music This series of concerts is based on my researches into 17th century English keyboard music, especially that of Matthew Locke and his Restoration colleagues, Albertus Bryne and John Roberts. Concert 1. "Melothesia restored". The keyboard music by Matthew Locke and his contemporaries. Given at the David Josefowitz Recital Hall, Royal Academy of Music on Tuesday SEP 30, 2003 Music by Matthew Locke (c.1622-77), Frescobaldi (1583-1643), Chambonnières (c.1602-72), William Gregory (fl 1651-87), Orlando Gibbons (1583-1625), Froberger (1616-67), Albert Bryne (c.1621-c.1670) This programmes sets a selection of Matthew Locke’s remarkable keyboard music within the wider context of seventeenth century keyboard playing. Although Locke confessed little admiration for foreign musical practitioners, he is clearly endebted to European influences. The un-measued prelude style which we find in the Prelude of the final C Major suite, for example, suggest a French influence, perhaps through the lutenists who came to London with the return of Charles II. Locke’s rhythmic notation belies the subtle inflections and nuances of what we might call the international style which he first met as a young man visiting the Netherlands with his future regal employer. One of the greatest keyboard players of his day, Froberger, visited London before 1653 and, not surprisingly, we find his powerful personality behind several pieces in Locke’s pioneering publication, Melothesia. As for other worthy composers of music for the harpsichord and organ, we have Locke's own testimony in his written reply to Thomas Salmon in 1672, where, in addition to Froberger, he mentions Frescobaldi and Chambonnières with the Englishmen John Bull, Orlando Gibbons, Albertus Bryne (his contemporary and organist of Westminster Abbey) and Benjamin Rogers.