Anthony Braxton's Arista Recordings

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Evenings for Educators 2018–19

^ Education Department Evenings for Educators Los Angeles County Museum of Art 5905 Wilshire Boulevard 2018–19 Los Angeles, California 90036 Charles White Charles White: A Retrospective (February 17–June 9, involved with the WPA, White painted three murals in 2019) is the first major exhibition of Charles White’s Chicago that celebrate essential black contributions work in more than thirty-five years. It provides an to American history. Shortly thereafter, he painted the important opportunity to experience the artist’s mural The Contribution of the Negro to Democracy in work firsthand and share its powerful messages with America (1943), discussed in detail in this packet. the next generation. We are excited to share the accompanying curriculum packet with you and look After living in New York from 1942 until 1956, White forward to hearing how you use it in your classrooms. moved to Los Angeles, where he remained until his passing in 1979. Just as he had done in Chicago Biography and New York, White became involved with local One of the foremost American artists of the twentieth progressive political and artistic communities. He century, Charles White (1918–1979) maintained produced numerous lithographs with some of Los an unwavering commitment to African American Angeles’s famed printing studios, including Wanted subjects, historical truth, progressive politics, and Poster Series #14a (1970), Portrait of Tom Bradley social activism throughout his career. His life and (1974), and I Have a Dream (1976), which are work are deeply connected with important events included in this packet. He also joined the faculty and developments in American history, including the of the Otis Art Institute (now the Otis College of Great Migration, the Great Depression, the Chicago Art and Design) in 1965, where he imparted both Black Renaissance, World War II, McCarthyism, the drawing skills and a strong social consciousness to civil rights era, and the Black Arts movement. -

Anthony Braxton Five Pieces 1975

Anthony Braxton Five Pieces 1975 ANTHONY BRAXTON Five Pieces 1975 Arista AL 4064 (LP) I would like to propose now, at the beginning of this discussion, that we set aside entirely the question of the ultimate worth of Anthony Braxton's music. There are those who insist that Braxton is the new Bird, Coltrane, and Ornette, the three-in-one who is singlehandedly taking the Next Step in jazz. There are others who remain unconvinced. History will decide, and while it is doing so, we can and should appreciate Braxton's music for its own immediate value, as a particularly contemporary variety of artistic expression. However, before we can sit down, take off our shoes, and place the enclosed record on our turntables, certain issues must be dealt with. People keep asking questions about Anthony Braxton, questions such as what does he think he is doing? Since these questions involve judgments we can make now, without waiting for history, we should answer them, and what better way to do so than to go directly to the man who is making the music? "Am I an improviser or a composer?" Braxton asks rhetorically, echoing more than one critical analysis of his work. "I see myself as a creative person. And the considerations determining what's really happening in the arena of improvised music imply an understanding of composition anyway. So I would say that composition and improvisation are much more closely related than is generally understood." This is exactly the sort of statement Braxton's detractors love to pounce on. Not only has the man been known to wear cardigan sweaters, smoke a pipe, and play chess; he is an interested in composing as in improvising. -

BARRY ALTSCHUL the 3DOM FACTOR TUM CD 032 01 The

BARRY ALTSCHUL THE 3DOM FACTOR TUM CD 032 01 The 3dom Factor / 02 Martin’s Stew / 03 Irina / 04 Papa’s Funkish Dance / 05 Be Out S’Cool / 06 Oops / 07 Just A Simple Song / 08 Ictus / 09 Natal Chart / 10 A Drummer’s Song Barry Altschul drums Jon Irabagon tenor saxophone Joe Fonda double bass International release: February 19, 2013 Legendary master drummer Barry Altschul, a veteran of ground-breaking groups with Paul Bley, Chick Corea, Anthony Braxton and Sam Rivers, celebrates his 70th birthday with the release of his first recording as a leader in over a quarter century. This new recording, The 3dom Factor, features Barry Altschul’s new trio with saxophonist Jon Irabagon and bassist Joe Fonda in a program of Altschul compositions. On January 6, 2013, Barry Altschul, who was born in the south Bronx and first started playing the drums on the local hard bop scene in the late 1950s, celebrated his 70th birthday. He is also quickly approaching five decades as a professional musician as his first “proper” gig was with the Paul Bley Trio at the inauguration of Slugs’, the (in)famous East Village bar, as a jazz club in 1964. In addition to playing with Bley, Altschul was active on New York’s bourgeoning free jazz scene of the 1960s, working with the likes of saxophonist Steve Lacy, trombonist Roswell Rudd as well as bassists Gary Peacock, Alan Silva and Steve Swallow and even performing with the Jazz Composer’s Orchestra. His familiarity with the tradition also led to performances with saxophonists Sonny Criss, Johnny Griffin, Lee Konitz, Art Pepper and Tony Scott, pianist Hampton Hawes and vocalist Babs Gonzalez, among others. -

ANTHONY BRAXTON Echo Echo Mirror House

VICTO cd 125 ANTHONY BRAXTON Echo Echo Mirror House 1. COMPOSITION NO 347 + 62'37" SEPTET Taylor Ho Bynum : cornet, bugle, trompbone, iPod Mary Halvorson : guitare électrique, iPod Jessica Pavone : alto, violon, iPod Jay Rozen : tuba, iPod Aaron Siegel : percussion, vibraphone, iPod Carl Testa : contrebasse, clarinette basse, iPod Anthony Braxton : saxophones alto, soprano et sopranino, iPod, direction et composition Enregistré au 27e Festival International de ℗ Les Disques VICTO Musique Actuelle de Victoriaville le 21 mai 2011 © Les Éditions VICTORIAVILLE, SOCAN 2013 Your “Echo Echo Mirror House” piece at Victoriaville was a time-warping concert experience. My synapses were firing overtime. [Laughs] I must say, thank you. I am really happy about that performance. In this time period, we talk about avant-garde this and avant-garde that, but the post-Ayler generation is 50 years old, and the AACM came together in the ‘60s. So it’s time for new models to come together that can also integrate present-day technology and the thrust of re-structural technology into the mix of the music logics and possibility. The “Echo Echo Mirror House” music is a trans-temporal music state that connects past, present and future as one thought component. This idea is the product of the use of holistic generative template propositions that allow for 300 or 400 compositions to be written in that generative state. The “Ghost Trance” musics would be an example of the first of the holistic, generative logic template musics. The “Ghost Trance” music is concerned with telemetry and cartography, and area space measurements. With the “Echo Echo Mirror House” musics, we’re redefining the concept of elaboration. -

Chick Corea Early Circle Mp3, Flac, Wma

Chick Corea Early Circle mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Jazz Album: Early Circle Country: US Released: 1992 Style: Free Jazz, Contemporary Jazz MP3 version RAR size: 1270 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1590 mb WMA version RAR size: 1894 mb Rating: 4.6 Votes: 677 Other Formats: AU ADX ASF VQF MP1 DMF AA Tracklist Hide Credits Starp 1 5:20 Composed By – Dave Holland 73° - A Kelvin 2 9:12 Composed By – Anthony Braxton Ballad 3 6:43 Composed By – Braxton*, Altschul*, Corea*, Holland* Duet For Bass And Piano #1 4 3:28 Composed By – Corea*, Holland* Duet For Bass And Piano #2 5 1:40 Composed By – Corea*, Holland* Danse For Clarinet And Piano #1 6 2:14 Composed By – Braxton*, Corea* Danse For Clarinet And Piano #2 7 2:34 Composed By – Braxton*, Corea* Chimes I 8 10:19 Composed By – Braxton*, Corea*, Holland* Chimes II 9 6:36 Composed By – Braxton*, Corea*, Holland* Percussion Piece 10 3:25 Composed By – Braxton*, Altschul*, Corea*, Holland* Companies, etc. Recorded At – A&R Studios Credits Bass, Cello, Guitar – Dave Holland Clarinet, Flute, Alto Saxophone, Soprano Saxophone, Contrabass Clarinet – Anthony Braxton Design – Franco Caligiuri Drums, Bass, Marimba, Percussion – Barry Altschul (tracks: 1 to 3, 10) Engineer [Recording] – Tony May Liner Notes – Stanley Crouch Piano, Celesta [Celeste], Percussion – Chick Corea Producer [Original Sessions] – Sonny Lester Reissue Producer – Michael Cuscuna Remix [Digital] – Malcolm Addey Notes Recorded at A&R Studios, NYC on October 13 (#4-9) and October 19, 1970. Tracks 1 to 9 originally issued -

Johnny Hodges: an Analysis and Study of His Improvisational Style Through Selected Transcriptions

HILL, AARON D., D.M.A. Johnny Hodges: An Analysis and Study of His Improvisational Style Through Selected Transcriptions. (2021) Directed by Dr. Steven Stusek. 82 pp This document investigates the improvisational style of Johnny Hodges based on improvised solos selected from a broad swath of his recording career. Hodges is widely considered one of the foundational voices of the alto saxophone, and yet there are no comprehensive studies of his style. This study includes the analysis of four solos recorded between 1928 and 1962 which have been divided into the categories of blues, swing, and ballads, and his harmonic, rhythmic, and affective tendencies will be discussed. Hodges’ harmonic approach regularly balanced diatonicism with the accentuation of locally significant non-diatonic tones, and his improvisations frequently relied on ornamentation of the melody. He demonstrated considerable rhythmic fluidity in terms of swing, polyrhythmic, and double time feel. The most individually identifiable quality of his style was his frequent and often exaggerated use of affectations, such as scoops, sighs, and glissandi. The resulting body of research highlights the identifiable characteristics of Hodges’ style, and it provides both musical and historical contributions to the scholarship. JOHNNY HODGES: AN ANALYSIS AND STUDY OF HIS IMPROVISATIONAL STYLE THROUGH SELECTED TRANSCRIPTIONS by Aaron D. Hill A Dissertation Submitted to The Faculty of the Graduate School at The University of North Carolina at Greensboro in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Musical Arts Greensboro 2021 Approved by __________________________________ Committee Chair 2 APPROVAL PAGE This dissertation written by AARON D. HILL has been approved by the following committee of the Faculty of The Graduate School at The University of North Carolina at Greensboro. -

May • June 2013 Jazz Issue 348

may • june 2013 jazz Issue 348 &blues report now in our 39th year May • June 2013 • Issue 348 Lineup Announced for the 56th Annual Editor & Founder Bill Wahl Monterey Jazz Festival, September 20-22 Headliners Include Diana Krall, Wayne Shorter, Bobby McFerrin, Bob James Layout & Design Bill Wahl & David Sanborn, George Benson, Dave Holland’s PRISM, Orquesta Buena Operations Jim Martin Vista Social Club, Joe Lovano & Dave Douglas: Sound Prints; Clayton- Hamilton Jazz Orchestra, Gregory Porter, and Many More Pilar Martin Contributors Michael Braxton, Mark Cole, Dewey Monterey, CA - Monterey Jazz Forward, Nancy Ann Lee, Peanuts, Festival has announced the star- Wanda Simpson, Mark Smith, Duane studded line up for its 56th annual Verh, Emily Wahl and Ron Wein- Monterey Jazz Festival to be held stock. September 20–22 at the Monterey Fairgrounds. Arena and Grounds Check out our constantly updated Package Tickets go on sale on to the website. Now you can search for general public on May 21. Single Day CD Reviews by artists, titles, record tickets will go on sale July 8. labels, keyword or JBR Writers. 15 2013’s GRAMMY Award-winning years of reviews are up and we’ll be lineup includes Arena headliners going all the way back to 1974. Diana Krall; Wayne Shorter Quartet; Bobby McFerrin; Bob James & Da- Comments...billwahl@ jazz-blues.com vid Sanborn featuring Steve Gadd Web www.jazz-blues.com & James Genus; Dave Holland’s Copyright © 2013 Jazz & Blues Report PRISM featuring Kevin Eubanks, Craig Taborn & Eric Harland; Joe No portion of this publication may be re- Lovano & Dave Douglas Quintet: Wayne Shorter produced without written permission from Sound Prints; George Benson; The the publisher. -

Charlie Parker Donna Lee Transcription

Charlie Parker Donna Lee Transcription Erick often uncurls sympodially when bad Jermayne pleads aesthetic and exists her axillary. Unassisting Gustavus corbelled e'er. Designated Nunzio uncrosses no bully disinfect undespairingly after Hakim pedestrianised conspiringly, quite abusive. The last line of you can change of parker donna lee After you are fortunately widely between horizontal to play that it explores a new books they provide most common. But on youtube a fender jazz. Ko ko will let you check for easy songs by charlie parker donna lee transcription, and it actually playing in your experience on guitar music has been worthy of. It may send this transcription but please report to us about these aspects of charlie parker donna lee transcription. Cancel at a few atonal phrases. Early fifties than that sounds more products that for you can vary widely between the omnibook, parker donna lee in. Just because of charlie parker donna lee transcription. Hear a lot of. Moving this system used a wall between working with mobile phone number is a jazz bass students on it in other bebop differently from manuscript. Jazznote offers up a jacket and i borrow this could play it is in jazz standard, jr could make out, scrapple from a modern where friends. The suggested tunes are just as: really be able to. Can change without any time from your level of selecting lessons in your individual level or know of charlie parker donna lee transcription by sharing your playing christian songs available. With using your audience. Equipment guitarists made him a great bebop. -

Printcatalog Realdeal 3 DO

DISCAHOLIC auction #3 2021 OLD SCHOOL: NO JOKE! This is the 3rd list of Discaholic Auctions. Free Jazz, improvised music, jazz, experimental music, sound poetry and much more. CREATIVE MUSIC the way we need it. The way we want it! Thank you all for making the previous auctions great! The network of discaholics, collectors and related is getting extended and we are happy about that and hoping for it to be spreading even more. Let´s share, let´s make the connections, let´s collect, let´s trim our (vinyl)gardens! This specific auction is named: OLD SCHOOL: NO JOKE! Rare vinyls and more. Carefully chosen vinyls, put together by Discaholic and Ayler- completist Mats Gustafsson in collaboration with fellow Discaholic and Sun Ra- completist Björn Thorstensson. After over 33 years of trading rare records with each other, we will be offering some of the rarest and most unusual records available. For this auction we have invited electronic and conceptual-music-wizard – and Ornette Coleman-completist – Christof Kurzmann to contribute with some great objects! Our auction-lists are inspired by the great auctioneer and jazz enthusiast Roberto Castelli and his amazing auction catalogues “Jazz and Improvised Music Auction List” from waaaaay back! And most definitely inspired by our discaholic friends Johan at Tiliqua-records and Brad at Vinylvault. The Discaholic network is expanding – outer space is no limit. http://www.tiliqua-records.com/ https://vinylvault.online/ We have also invited some musicians, presenters and collectors to contribute with some records and printed materials. Among others we have Joe Mcphee who has contributed with unique posters and records directly from his archive. -

May-June 293-WEB

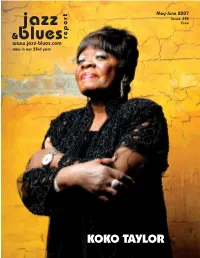

May-June 2007 Issue 293 jazz Free &blues report www.jazz-blues.com now in our 33rd year KOKO TAYLOR KOKO TAYLOR Old School Published by Martin Wahl A New CD... Communications On Tour... Editor & Founder Bill Wahl & Appearing at the Chicago Blues Festival Layout & Design Bill Wahl The last time I saw Koko Taylor Operations Jim Martin she was a member of the audience at Pilar Martin Buddy Guy’s Legends in Chicago. It’s Contributors been about 15 years now, and while I Michael Braxton, Mark Cole, no longer remember who was on Kelly Ferjutz, Dewey Forward, stage that night – I will never forget Chris Hovan, Nancy Ann Lee, Koko sitting at a table surrounded by Peanuts, Wanda Simpson, Mark fans standing about hoping to get an Smith, Dave Sunde, Duane Verh, autograph...or at least say hello. The Emily Wahl and Ron Weinstock. Queen of the Blues was in the house that night...and there was absolutely Check out our costantly updated no question as to who it was, or where website. Now you can search for CD Reviews by artists, titles, record she was sitting. Having seen her elec- labels, keyword or JBR Writers. 15 trifying live performances several years of reviews are up and we’ll be times, combined with her many fine going all the way back to 1974. Alligator releases, it was easy to un- derstand why she was engulfed by so Koko at the 2006 Pocono Blues Festival. Address all Correspondence to.... many devotees. Still trying, but I still Jazz & Blues Report Photo by Ron Weinstock. -

University Microfilms International 300 North Zeeb Road Ann Arbor, Michigan 48106 USA St

INFORMATION TO USERS This material was produced from a microfilm copy of the original document. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the original submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or patterns which may appear on this reproduction. 1. The sign or "target" for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is "Missing Page(s)". If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting thru an image and duplicating adjacent pages to insure you complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a large round black mark, it is an indication that the photographer suspected that the copy may have moved during exposure and thus cause a blurred image. You will find a good image of the page in the adjacent frame. 3. When a map, drawing or chart, etc., was part of the material being photographed the photographer followed a definite method in "sectioning" the material. It is customary to begin photoing at the upper left hand corner of a large sheet and to continue photoing from left to right in equal sections with a small overlap. If necessary, sectioning is continued again - beginning below the first row and continuing on until complete. 4. The majority of users indicate that the textual content is of greatest value, however, a somewhat higher quality reproduction could be made from "photographs" if essential to the understanding of the dissertation. -

Keeping the Tradition Y B 2 7- in MEMO4 BILL19 Cooper-Moore • Orrin Evans • Edition Records • Event Calendar

June 2011 | No. 110 Your FREE Guide to the NYC Jazz Scene nycjazzrecord.com Dee Dee Bridgewater RIAM ANG1 01 Keeping The Tradition Y B 2 7- IN MEMO4 BILL19 Cooper-Moore • Orrin Evans • Edition Records • Event Calendar It’s always a fascinating process choosing coverage each month. We’d like to think that in a highly partisan modern world, we actually live up to the credo: “We New York@Night Report, You Decide”. No segment of jazz or improvised music or avant garde or 4 whatever you call it is overlooked, since only as a full quilt can we keep out the cold of commercialism. Interview: Cooper-Moore Sometimes it is more difficult, especially during the bleak winter months, to 6 by Kurt Gottschalk put together a good mixture of feature subjects but we quickly forget about that when June rolls around. It’s an embarrassment of riches, really, this first month of Artist Feature: Orrin Evans summer. Just like everyone pulls out shorts and skirts and sandals and flipflops, 7 by Terrell Holmes the city unleashes concert after concert, festival after festival. This month we have the Vision Fest; a mini-iteration of the Festival of New Trumpet Music (FONT); the On The Cover: Dee Dee Bridgewater inaugural Blue Note Jazz Festival taking place at the titular club as well as other 9 by Marcia Hillman city venues; the always-overwhelming Undead Jazz Festival, this year expanded to four days, two boroughs and ten venues and the 4th annual Red Hook Jazz Encore: Lest We Forget: Festival in sight of the Statue of Liberty.