UNIVERSITY of CINCINNATI July 26, 2005 Susan Streeter Carpenter

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ABSTRACT “Our Grand Narrative of Women and War”: Writing, And

ABSTRACT “Our Grand Narrative of Women and War”: Writing, and Writing Past, a Gendered Understanding of War Front and Home Front in the War Writing of Hemingway, O’Brien, Plath, and Salinger Julie Ooms, Ph.D. Mentor: Luke Ferretter, Ph.D. Scholars and theorists who discuss the relationship between gender and war agree that the divide between the war front and the home front is gendered. This boundary is also a cause of pain, of misunderstanding, and of the breakdown of community. One way that soldiers and citizens, men and women, on either side of the boundary can rebuild community and find peace after war is to think—and write—past this gendered understanding of the divide between home front and war front. In their war writing, the four authors this dissertation explores—Ernest Hemingway, Tim O’Brien, Sylvia Plath, and J.D. Salinger—display evidence of this boundary, as well as its destructive effects on persons on both sides of it. They also, in different ways, and with different levels of success, write or begin to write past this boundary and its gendered understanding of home front and war front. Through my exploration of these four authors’ work, I conclude that the war writers of the twentieth century have a problem to solve: they still write within an understanding of war that very clearly genders combatants and noncombatants, warriors and home front helpers. However, they also live and write within a historical and political era that opens up a greater possibility to think and write past this gendered understanding. -

Loretta Lynn the Pill / Will You Be There Mp3, Flac, Wma

Loretta Lynn The Pill / Will You Be There mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Folk, World, & Country Album: The Pill / Will You Be There Country: UK Released: 1975 Style: Country MP3 version RAR size: 1318 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1326 mb WMA version RAR size: 1349 mb Rating: 4.8 Votes: 230 Other Formats: AHX AAC AUD APE AIFF DMF MMF Tracklist A The Pill 2:35 B Will You Be There 2:19 Other versions Category Artist Title (Format) Label Category Country Year The Pill / Will You Be MCA-40358 Loretta Lynn MCA Records MCA-40358 US 1975 There (7") The Pill (7", Single, MCA 193 Loretta Lynn MCA Records MCA 193 UK 1975 Promo) The Pill / Will You Be MCA1431 Loretta Lynn MCA Records MCA1431 Australia 1975 There (7") The Pill / Will You Be MCA 193 Loretta Lynn MCA Records MCA 193 UK 1975 There (7") MCA-40358 Loretta Lynn The Pill (7", Single) MCA Records MCA-40358 US 1975 Related Music albums to The Pill / Will You Be There by Loretta Lynn Loretta Lynn - I Lie / If I Ain't Got It ( You Don't Need It ) Loretta Lynn - Heart Don't Do This To Me Loretta Lynn - Coal Miner's Daughter Loretta Lynn - Loretta Lynn's Greatest Hits Loretta Lynn - The Darkest Day Loretta Lynn - The Country Music Hall Of Fame Loretta Lynn - One's On The Way Loretta Lynn - Loretta Lynn's Greatest Hits Vol. II Loretta Lynn=Promo - RARE DJ/PROMO COPY- Loretta Lynn-Dear Uncle Sam-DEC-31893-rare color Loretta Lynn - The Coal Miner's Daughter Loretta Lynn - Greatest Hits Live Loretta Lynn Conway Twitty - As Soon As I Hang Up The Phone. -

Jane the Virgin”

Culture, ethnicity, religion, and stereotyping in the American TV show “Jane the Virgin” Fares 2 Contents Introduction………………………………………………………………………..…………….….3 1. Theory & Methodology……………………………………………..………..……………….…4 2. Cultural theory……………………………………………………………..…………………….6 2.1 stereotypes and their Functions: ‘othering’, ‘alterity’, ‘us’ and ‘them’ dichotomy……………………………………………………………...…..…6 2.2 race and ethnicity………………….……..…………………….......….16 2.3 religion………………………………………………………………......18 2.4 virginity and ‘marianismo’..……………………………………….…...19 2.5 identity…………………….………………………...….……………….20 3. Media Context….…………………….……………………...…………………………………24 3.1 postmodernism and television..………………...………………..…24 3.2 Latin American soap operas…………………………………….…..27 3.3 American soap operas ………………………………………..….….31 4. Genre Analysis Context…….…………………………………………………………………33 4.1 genre theory and concepts...…………………………………..……34 4.2 comedy..………………………………………………………...….…38 5. Cultural Analysis oF “Jane The Virgin”……………………………………………………….42 6. Genre Analysis oF “Jane the Virgin”…………………………………………………….……61 7. Comparison & Discussion………………………………………………...…………….…….72 8. Conclusion…………………………………………………………………..………………….75 9. Works Cited…………………..……………………………………………..………………….77 Fares 3 Adalat Lena Fares Bent Sørensen Master’s Thesis 2. June 2020 Culture, ethnicity, religion, and stereotyping in the American TV show "Jane the Virgin" "Jane the Virgin" is an American television show on The CW, that parodies the Latin American soap opera format, while also depicting and handling real-life issues. The -

![[E:] 09 a Second Face.Mp3=2129222 ACDC Whole Lotta Rosie (Rare Live](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/7220/e-09-a-second-face-mp3-2129222-acdc-whole-lotta-rosie-rare-live-217220.webp)

[E:] 09 a Second Face.Mp3=2129222 ACDC Whole Lotta Rosie (Rare Live

mTad [E:] 09 A Second face.mp3=2129222 ACDC Whole Lotta Rosie (rare live Bon Scott).mp3=4874280 Damnation of Adam Blessing - Second Damnation - 05 - Back to the River.mp3=5113856 Eddie Van Halen - Eruption (live, rare).mp3=2748544 metallica - CreepingDeath (live).mp3=4129152 [E:\1959 - Miles Davis - Kind Of Blue] 01 So What.mp3=13560814 02 Freddie Freeloader.mp3=14138851 03 Blue In Green.mp3=8102685 04 All Blues.mp3=16674264 05 Flamenco Sketches.mp3=13561792 06 Flamenco Sketches (Alternate Take).mp3=13707024 B000002ADT.01.LZZZZZZZ.jpg=19294 Thumbs.db=5632 [E:\1965 - The Yardbirds & Sonny Boy Williamson] 01 - Bye Bye Bird.mp3=2689034 02 - Mister Downchild.mp3=4091914 03 - 23 Hours Too Long.mp3=5113866 04 - Out Of The Water Coast.mp3=3123210 05 - Baby Don't Worry.mp3=4472842 06 - Pontiac Blues.mp3=3864586 07 - Take It Easy Baby (Ver 1).mp3=4153354 08 - I Don't Care No More.mp3=3166218 09 - Do The Weston.mp3=4065290 10 - The River Rhine.mp3=5095434 11 - A Lost Care.mp3=2060298 12 - Western Arizona.mp3=2924554 13 - Take It Easy Baby (Ver 2).mp3=5455882 14 - Slow Walk.mp3=1058826 15 - Highway 69.mp3=3102730 albumart_large.jpg=11186 [E:\1971 Nazareth] 01 - Witchdoctor Woman.mp3=3994574 02 - Dear John.mp3=3659789 03 - Empty Arms, Empty Heart.mp3=3137758 04 - I Had A Dream.mp3=3255194 05 - Red Light Lady.mp3=5769636 06 - Fat Man.mp3=3292392 07 - Country Girl.mp3=3933959 08 - Morning Dew.mp3=6829163 09 - The King Is Dead.mp3=4603112 10 - Friends (B-side).mp3=3289466 11 - Spinning Top (alternate edit).mp3=2700144 12 - Dear John (alternate edit).mp3=2628673 -

Reimagining the Mac Practicum Signal Mtn

THEFriday, December 5, 2014 - Vol. 61.11 14049 Scenic Highway,BAGPIPE Lookout Mountain, GA 30750 www.bagpipeonline.com The Real Cost Reimagining the Mac Practicum Signal Mtn. of Covenant Cameras BY EMMETT GIENAPP BY CAROLYN WALTERS While the thought of just dropping On Nov. 21, the Signal Mountain out may become more appealing town council met to discuss to some students as final exams the installation of license plate approach, there is at least one cameras as a response to a recent piece of good news to keep in string of home burglaries in the mind—Covenant College is still area. Nineteen burglaries have cheaper than most of its four-year occurred in the town over the competitors in the regional south. course of the past year, the majority U.S. News and World Report of which took place during a period recently showed in their annual that began in late August. report on higher education costs By the first week of September, that the average total indebtedness police were investigating the of Covenant students was $22,790. robberies of six separate homes. While that number is daunting in This prompted town manager Boyd its own right, it’s still below the Veal to issue a warning to residents national average of $29,400. via email, encouraging homeowners The upfront cost and total debt to be observant and to routinely use BY KRISTIE JAYA that students carry with them has Additionally, the internship will space for it. “While the practicum their alarm systems. become more of a concern not Mac Practicum, a project required be for academic credit and will has some very beneficial pieces, According to Signal Mountain’s just at Covenant, but at colleges for all Maclellan Scholars require approval by the college. -

2006 City Park Jazz Schedule

2017 FREE & CHEAP HAPPENINGS IN METRO DENVER Contact email: [email protected] Created By: Deahna Visscher Created on: May 25, 2017 This list is created manually each year by me gathering information on every website that is included in this document. I create this list annually, as a form of community service and as a way of paying it forward so that as many people as possible can benefit from the information and enjoy what our cities have to offer. Please feel free to pass this on to all your family, friends, co-workers, and customers. Also, please feel free to post this at your work, churches, community centers, etc. If you are on Facebook check out the Free & Cheap Happenings in Metro Denver group page. This group page contains the full free list document as well as events that I discover throughout the year that aren’t yet on the list: https://www.facebook.com/groups/1572112826421872/ I hope you have a wonderful summer full of FREE and CHEAP HAPPENINGS IN METRO DENVER! P.S. If you are an event organizer I did my best to find all the events posted on the web for your city or event. For next year, please feel free to send me your event listings by May 1 and I will gladly add them to my list. Thanks! Also, if you know of an event that was not listed, please send it to me in an email so that I can post it on the Free & Cheap Happening in Metro Denver Facebook group and so I can add it to next years list. -

JULY—1977 TNNSYLVANIA The

JULY—1977 TNNSYLVANIA the KeystoneH State's / * Official FISHING BOATING Magazine... ^J 30c il agw. Single Copy ITS UPHILL... ALL THE WAY! ifty years ago Lindbergh made his solo flight across the Atlantic and those F of us who were boys at the time remember the thrill we felt over his ac complishment . how, for several years afterward, we wore "Lindy" leather helmets (with goggles on the forehead!) to school and wished for the same op portunity for glory and accomplishment. Less than two years later our families were knocked to their knees by the Great Depression. Only the necessities of life took on any real value and everybody in the family earned his own way. If you wanted something, you earned the money to pay for it; if you didn't earn it, you went without. A generation later, despite having what are now called "recessions," Americans have, in many ways and for one reason or another, turned around 180 degrees, determining that their children will never have to suffer the deprivations they endured. This is a tragic turnaround, in a number of ways. One- third of our state budget is dedicated to welfare and other giveaways. And, significant among the giveaways — it seems that every time someone thinks of giving something free, they think of fishing! When the Fish Commission asked the General Assembly in early March for an increase in its license fee, the enlightened members of that body required that the bill include a juvenile license, one just as we had asked for in 1973. It is amazing how much negative reaction can be generated by this small request. -

(Pdf) Download

Artist Song 2 Unlimited Maximum Overdrive 2 Unlimited Twilight Zone 2Pac All Eyez On Me 3 Doors Down When I'm Gone 3 Doors Down Away From The Sun 3 Doors Down Let Me Go 3 Doors Down Behind Those Eyes 3 Doors Down Here By Me 3 Doors Down Live For Today 3 Doors Down Citizen Soldier 3 Doors Down Train 3 Doors Down Let Me Be Myself 3 Doors Down Here Without You 3 Doors Down Be Like That 3 Doors Down The Road I'm On 3 Doors Down It's Not My Time (I Won't Go) 3 Doors Down Featuring Bob Seger Landing In London 38 Special If I'd Been The One 4him The Basics Of Life 98 Degrees Because Of You 98 Degrees This Gift 98 Degrees I Do (Cherish You) 98 Degrees Feat. Stevie Wonder True To Your Heart A Flock Of Seagulls The More You Live The More You Love A Flock Of Seagulls Wishing (If I Had A Photograph Of You) A Flock Of Seagulls I Ran (So Far Away) A Great Big World Say Something A Great Big World ft Chritina Aguilara Say Something A Great Big World ftg. Christina Aguilera Say Something A Taste Of Honey Boogie Oogie Oogie A.R. Rahman And The Pussycat Dolls Jai Ho Aaliyah Age Ain't Nothing But A Number Aaliyah I Can Be Aaliyah I Refuse Aaliyah Never No More Aaliyah Read Between The Lines Aaliyah What If Aaron Carter Oh Aaron Aaron Carter Aaron's Party (Come And Get It) Aaron Carter How I Beat Shaq Aaron Lines Love Changes Everything Aaron Neville Don't Take Away My Heaven Aaron Neville Everybody Plays The Fool Aaron Tippin Her Aaron Watson Outta Style ABC All Of My Heart ABC Poison Arrow Ad Libs The Boy From New York City Afroman Because I Got High Air -

Touring Biz Awaits Rap Boom

Y2,500 (JAPAN) $6.95 (U.S.), $8.95 (CAN.), £5.50 (U.K.), 8.95 (EUROPE), II1I11 111111111111 IIIIILlll I !Lull #BXNCCVR 3 -DIGIT 908 #90807GEE374EM002# BLBD 863 A06 B0116 001 MAR 04 2 MONTY GREENLY 3740 ELM AVE # A LONG BEACH CA 90807 -3402 HOME ENTERTAINMENT THE INTERNATIONAL NEWSWEEKLY OF MUSIC, VIDEO, AND Labels Hitching Stars To Clive Greeted As New RCA Chief Global Consumer Brands Artists, Managers Heap Praise On Davis, But Some Just Want Stability given five -year contracts, according BY MELINDA NEWMAN BY BRIAN GARRITY Goldstuck had been pres- While managers of acts signed to to Davis. NEW YORK -In the latest sign of J Records. Richard RCA Records are quick to praise out- ident/C00 that the marketing of music is will continue as executive going RCA Music Group (RMG) Sanders undergoing a sea change, the RCA Records. chairman Bob Jamieson, they are also VP /GM of major labels are forging closer ties "We absolutely loved and have heralding the news that J Records with global consumer brands in with Bob Jamieson head Clive Davis will now control enjoyed working an effort to gain exposure for their and hope our paths will cross with him both the J label and RCA Records. acts. As the deals become more says artist manager Irving BMG announced Nov. 19 that it is again," pervasive, they raise questions for whose client Christina Aguilera buying out Davis' 50 %, stake in J Azoff, artists, who have typically cut on RCA Oct. 29. "I've Records -the label he formed in released Stripped their own sponsorship deals. -

CASS CITY CHRONICLE I

CASS CITY CHRONICLE d tTI [ • ' Ul=: ~ I I ir i H~-~_ .... VOLUME 29,' NUMBER 2. CASS CITY, MICHIGAN, FRIDAY, APRIL 20, 1934. EIGHT PAGES. ] I Prayer and offering 4-H ACHIEVEMENT DAYS. COUNCIL NAMED MAY 14-15 March, "Adoration"....H.C. Miller AS CLEAN-UP DAYS HERE LOU H A [ iS Andante, "The Old Church Or~ 50TH ANN!WR R ' gan'. ................... W. P. Chambers 4-11 achiev¢.~nen~ days will bc The Band observed in Tuscola county at the At the council meeting Monday AI iED 81RGUITJUDE"Soft Shadows Falling"..Flemming following places next week: U RISE [ OLO Y evening, the trustees set aside May i FV FLli AL [ HURI H Boys' Glee Club Mayville , Monday evening, Apr. 14 and 15 as clean-up days in Cass , ,, "March Romaine". .............F. Beyer 23, at high school. T City. Trucks will be furnished by Serenade, "The Twilight Hour" Delegates Coming Here from Millington, Tuesday afternoon the village to cart away tin cans Lapeer Attorney Fills Vacan- ..........................Francis A. Myers L. D. Randall Speaks on Ag- ~Large Numbers Attended the Apr. 24, at M. E. church. t and other rubbish which are ,to be cy Caused bY Death of The Band Fifty Parishes in Thumb Akron, Tuesday evening, April ricultural Experiment placed at a convenient spot for Banquet and Two Sunday "Go Where the Water Glideth" Judge Smith. on May 5. 2~, at community hall. Near Chesaning. loading. Ash hauling will not be ..............................................Wilson Caro, Wednesday afternoon, Apr. done b:~ the village trucks. Services. Girls' Glee Club 25, at high school auditorium. -

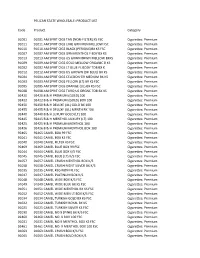

(NON-FILTER) KS FSC Cigarettes: Premiu

PELICAN STATE WHOLESALE: PRODUCT LIST Code Product Category 91001 91001 AM SPRIT CIGS TAN (NON‐FILTER) KS FSC Cigarettes: Premium 91011 91011 AM SPRIT CIGS LIME GRN MEN MELLOW FSC Cigarettes: Premium 91010 91010 AM SPRIT CIGS BLACK (PERIQUE)BX KS FSC Cigarettes: Premium 91007 91007 AM SPRIT CIGS GRN MENTHOL F BDY BX KS Cigarettes: Premium 91013 91013 AM SPRIT CIGS US GRWN BRWN MELLOW BXKS Cigarettes: Premium 91009 91009 AM SPRIT CIGS GOLD MELLOW ORGANIC B KS Cigarettes: Premium 91002 91002 AM SPRIT CIGS LT BLUE FL BODY TOB BX K Cigarettes: Premium 91012 91012 AM SPRIT CIGS US GROWN (DK BLUE) BX KS Cigarettes: Premium 91004 91004 AM SPRIT CIGS CELEDON GR MEDIUM BX KS Cigarettes: Premium 91003 91003 AM SPRIT CIGS YELLOW (LT) BX KS FSC Cigarettes: Premium 91005 91005 AM SPRIT CIGS ORANGE (UL) BX KS FSC Cigarettes: Premium 91008 91008 AM SPRIT CIGS TURQ US ORGNC TOB BX KS Cigarettes: Premium 92420 92420 B & H PREMIUM (GOLD) 100 Cigarettes: Premium 92422 92422 B & H PREMIUM (GOLD) BOX 100 Cigarettes: Premium 92450 92450 B & H DELUXE (UL) GOLD BX 100 Cigarettes: Premium 92455 92455 B & H DELUXE (UL) MENTH BX 100 Cigarettes: Premium 92440 92440 B & H LUXURY GOLD (LT) 100 Cigarettes: Premium 92445 92445 B & H MENTHOL LUXURY (LT) 100 Cigarettes: Premium 92425 92425 B & H PREMIUM MENTHOL 100 Cigarettes: Premium 92426 92426 B & H PREMIUM MENTHOL BOX 100 Cigarettes: Premium 92465 92465 CAMEL BOX 99 FSC Cigarettes: Premium 91041 91041 CAMEL BOX KS FSC Cigarettes: Premium 91040 91040 CAMEL FILTER KS FSC Cigarettes: Premium 92469 92469 CAMEL BLUE BOX -

Q2 2011 Full Announcement

2011 FIRST HALF YEAR RESULTS CONTINUING GOOD PROGRESS DESPITE DIFFICULT MARKETS First Half Highlights • Strong second quarter underlying sales growth 7.1%; first half underlying sales growth 5.7% comprising volume growth 2.2% and price growth 3.5%. • Turnover up 4.1% at €22.8 billion with a negative impact from foreign exchange of 1.6%. • Underlying operating margin down 20bps; impact of high input cost inflation mitigated by pricing and savings. Stepped-up continuous improvement programmes generated efficiencies in advertising and promotions and led to lower indirect costs. • Advertising and promotions expenditure, at around €3 billion, was higher than the second half of 2010 but down 150bps versus the exceptionally high prior year comparator. • Fully diluted earnings per share up 10% at €0.77. • Integration of Sara Lee brands largely complete and Alberto Culver progressing rapidly. The acquisition of the laundry business in Colombia completed. Chief Executive Officer “We are making encouraging progress in the transformation of Unilever to a sustainable growth company. In a tough and volatile environment we have again delivered strong growth. Volumes were robust and in line with the market, despite having taken price increases. This shows the strength of our brands and innovations. Our emerging markets business continues to deliver double digit growth. Performance in Western Europe was also strong in the second quarter so that the half year results reflect the true progress we have been making. Bigger and better innovation rolled out faster and moving our brands into white spaces continue to be the biggest drivers of growth. We are now striving to go further and faster still.