Speed of Person Perception Affects Immediate and Ongoing Aesthetic

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

3"T *T CONVERSATIONS with the MASTER: PICASSO's DIALOGUES

3"t *t #8t CONVERSATIONS WITH THE MASTER: PICASSO'S DIALOGUES WITH VELAZQUEZ THESIS Presented to the Graduate Council of the University of North Texas in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS By Joan C. McKinzey, B.F.A., M.F.A. Denton, Texas August 1997 N VM*B McKinzey, Joan C., Conversations with the master: Picasso's dialogues with Velazquez. Master of Arts (Art History), August 1997,177 pp., 112 illustrations, 63 titles. This thesis investigates the significance of Pablo Picasso's lifelong appropriation of formal elements from paintings by Diego Velazquez. Selected paintings and drawings by Picasso are examined and shown to refer to works by the seventeenth-century Spanish master. Throughout his career Picasso was influenced by Velazquez, as is demonstrated by analysis of works from the Blue and Rose periods, portraits of his children, wives and mistresses, and the musketeers of his last years. Picasso's masterwork of High Analytical Cubism, Man with a Pipe (Fort Worth, Texas, Kimbell Art Museum), is shown to contain references to Velazquez's masterpiece Las Meninas (Madrid, Prado). 3"t *t #8t CONVERSATIONS WITH THE MASTER: PICASSO'S DIALOGUES WITH VELAZQUEZ THESIS Presented to the Graduate Council of the University of North Texas in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS By Joan C. McKinzey, B.F.A., M.F.A. Denton, Texas August 1997 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The author would like to acknowledge Kurt Bakken for his artist's eye and for his kind permission to develop his original insight into a thesis. -

![Modern Art University of Texas at Arlington, Fall 2013 Fine Arts Building [FA] 2102A, Monday, Wednesday, Friday 9:00-9:50Am](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/9060/modern-art-university-of-texas-at-arlington-fall-2013-fine-arts-building-fa-2102a-monday-wednesday-friday-9-00-9-50am-1319060.webp)

Modern Art University of Texas at Arlington, Fall 2013 Fine Arts Building [FA] 2102A, Monday, Wednesday, Friday 9:00-9:50Am

UPDATED AUGUST 23 Art 3314: Modern Art University of Texas at Arlington, Fall 2013 Fine Arts Building [FA] 2102A, Monday, Wednesday, Friday 9:00-9:50am Description: This course provides an introduction to the art of the first half of the twentieth century. It is concerned with both the formal analysis of artworks and their historical context. The lectures and readings are integrated with important works from the collections of art museums in Dallas and Fort Worth. Instructor: Dr. Benjamin Lima, Fine Arts 2101, (214) 517-8733 [email protected] Office hours: Mondays and Wednesdays 11:00 to noon. Sign up here for appointments http://goo.gl/ozd2j Student Learning Outcomes: 1. To become familiar with the major artists, themes and movements in European art between 1900 and 1945. 2. To gain experience with close firsthand observation of art in museums, developing observational and analytical skills. 3. To be able to interpret works of modern art both through visual analysis of a work itself, and in light of historically important interpretations given to works by artists, critics, and scholars. 4. To develop research, observational and organizational skills in preparing a written assignment. 5. To develop communication and analytical skills in presenting the results of research and study. Textbooks: The two textbooks for the course are available at the UTA bookstore (817-272-5757), as well as in the Visual Resource Commons (Fine Arts 2109, open Monday-Friday 8:30am-5:00pm). They will also be on reserve in the Architecture & Fine Arts Library. 1. Art Since 1900, Volume 1: 1900 to 1944, second edition [ASN] (Thames and Hudson, 2011; ISBN 0500289522) 2. -

Picasso and Braque First Exhibition to Unite Works from Pivotal Years of 1910-12

Contact: Katrina Carl (805) 884-6430 [email protected] Left image: Pablo Picasso, Portrait of a Woman, 1910. Oil on canvas. Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. Right image: Georges Braque, Girl with a Cross, 1911. Oil on canvas. Kimbell Art Museum. Picasso and Braque First Exhibition to Unite Works from Pivotal Years of 1910-12 On View September 17, 2011 – January 8, 2012 April 4, 2011 - Picasso and Braque: The Cubist Experiment, 1910–1912, the first exhibition to unite many of the paintings and nearly all of the prints created by Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque during these two exhilarating years of their artistic dialogue, goes on view at the Santa Barbara Museum of Art (SBMA) on September 17. The international loan exhibition, featuring 16 paintings and 20 etchings and drypoints, is organized by the Santa Barbara Museum of Art and the Kimbell Art Museum, with its debut in Fort Worth, TX May 29 – August 21, 2011. “This will be the first presentation ever held on the West Coast devoted to this seminal and fascinating phase of modern art, and it will forever change our understanding of the experimental link between these great masters,” states Larry Feinberg, SBMA Director. During the years 1910 through 1912, Picasso and Braque invented a new style that took the basics of traditional European art—modeling in light and shade to suggest roundedness, perspective lines to suggest space, indeed the very idea of making a recognizable description of the real world—and toyed with them irreverently. Eik Kahng, organizing curator and SBMA Chief Curator notes, “The works that these two artists produced during this two year period remain some of the most difficult and enigmatic in all of the history of art. -

Picasso's Masterpiece

This script was freely downloaded from the (re)making project, (charlesmee.org). We hope you'll consider supporting the project by making a donation so that we can keep it free. Please click here to make a donation. Picasso’s Masterpiece by C H A R L E S L . M E E Picasso's studio in Montmartre, filled with dozens of canvases on easels, scattered chairs, canvases everywhere on the floor, leaning against the walls, lots of plates and bowls—ceramics— a rocking chair, a couple of couches, a potbellied stove, pedestals with busts and ceramic vases on them. This piece can be done in a proscenium theatre or in a big black box—as an immersive event, with the audience sitting among the easels and chairs and bowls on the floor— and/or as a completely immersive experience with all of Picasso's paintings projected on the floors and walls and ceilings, constantly changing in ultra slow motion— like the Picasso show that was done in the Cathedral d'Images in Les Baux de Provence. We hear music by Satie and then Picasso enters and, taking his time, starts to paint. Satie music Satie music Satie music Satie music Satie music Satie music Satie music Satie music Satie music Satie music Satie music Satie music Satie music Satie music Satie music Satie music Satie music Satie music A man enters silently, looks at what Picasso is painting and then starts speaking/singing to Satie's music: SOLO grapes in profile on the swarming blues the blue striped t-shirt and the greenish blue the sugared blue slapped on the pink the purple diaper of the lilac bunched -

Imogen Racz Volume 1

HENRI LAURENS AND THE PARISIAN AVANT-GARDE IMOGEN RACZ NEWCASTLE UNIVERSITY LIBRARY 099 19778 0 -' ,Nesis L6 VOLUME 1 Thesis submitted for the degree of PhD. The University of Newcastle. 2000. Abstract This dissertation examines the development of Henri Laurens' artistic work from 1915 to his death in 1954. It is divided into four sections: from 1915 to 1922, 1924 to 1929, 1930 to 1939 and 1939 to 1954. There are several threads that run through the dissertation. Where relevant, the influence of poetry on his work is discussed. His work is also analyzed in relation to that of the Parisian avant-garde. The first section discusses his early Cubist work. Initially it reflected the cosmopolitan influences in Paris. With the continuation of the war, his work showed the influence both of Leonce Rosenberg's 'school' of Cubism and the literary subject of contemporary Paris. The second section considers Laurens' work in relation to the expanding art market. Laurens gained a number of public commissions as well as many ones for private clients. Being site specific, all the works were different. The different needs of architectural sculpture as opposed to studio sculpture are discussed, as is his use of materials. Although the situation was not easy for avant-garde sculptors, Laurens became well respected through exposure in magazines and exhibitions. The third section considers Laurens in relation to the depression and the changing political scene. Like many of the avant-garde, he had left wing tendencies, which found form in various projects, including producing a sculpture for the Ecole Karl Marx at Villejuif. -

Making Myths Contents

TEACHERS’ RESOURCE MAKING MYTHS CONTENTS 1: MAKING MYTHS: THE STORIES TOLD BY ARTISTS, CURATORS, COLLECTORS AND CONSERVATORS 2: COLLECTING GAUGUIN: CURATOR’S QUESTIONS 3: RE-INVENTING MYTH: FORM AND FUNCTION IN SOME EARLY MODERN ‘MYTHOLOGICAL’ WORKS FROM THE COURTAULD GALLERY 4: MANET, DEGAS, RENOIR AND THE THEATRE OF EVERYDAY LIFE 5: TAKEN AT FACE VALUE? SELF-STAGING AND MYTH-MAKING IN THE WORK OF GAUGUIN AND VAN GOGH 6: THE MATERIAL LANGUAGE OF PAINTINGS: CONSERVATION AND TECHNICAL ART HISTORY 7: REGARDE! FRENCH LANGUAGE RESOURCE: GAUGUIN ET LA POLYNÉSIE 8: GLOSSARY 9: SUGGESTIONS FOR RESEARCH AND PRACTICAL ACTIVITIES IN THE CLASSROOM 10: TEACHING RESOURCE IMAGE CD Compiled and produced by Carolin Levitt and Sarah Green Design by JWDesigns SUGGESTED CURRICULUM LINKS FOR EACH ESSAY ARE MARKED IN RED TERMS REFERRED TO IN THE GLOSSARY ARE MARKED IN BLUE To book a visit to the gallery or to discuss any of the education projects at The Courtauld Gallery please contact: e: [email protected] t: 0207 848 1058 WELCOME The Courtauld Institute of Art runs an exceptional programme of activities suitable for young people, school teachers and members of the public, whatever their age or background. We offer resources which contribute to the understanding, knowledge and enjoyment of art history based upon the world-renowned art collection and the expertise of our students and scholars. I hope the material will prove to be both useful and inspiring. Henrietta Hine Head of Public Programmes The Courtauld Institute of Art This resource offers teachers and their students an opportunity to explore the wealth of The Courtauld Gallery’s permanent collection by expanding on a key idea drawn from our exhibition programme. -

Untitled», 36X34", Oil on Canvas

(AZEM) Azerbaljani Fellow Countrymen Community The New York Azerbaljani Association The US Caucasus Jews Culture Association Supported by: The State CommJttee on Diaspora Issues of the Republic of .Azerba.(/an Republic and the Permanent Mission of .Azerba.(/an to The United Nations TH£ FlRST £XHlB1TlON of tl1� Az�rbaif atti Diaspora Artists itt tl1� VSA March 2009, New York CURATOR: Nobert YEVDAYEV CATALOGUE DESIGN: Ismail MAMMADOV COMPUTER DESIGN: Mikhail KUROV LIST OF PARTICIPANTS: Nahum TSCHACBASOV Nobert YEVDAYEV lsmayil MAMMADOV Boris RAKHAMIMOV Elnur BABAYEV Aga OUSSEINOV Emin GULIYEV Adil VEZIROV EXHIBITION ORG ANIZERS: Nobert YEVDAYEV Yakov ABRAMOV Ali NASIBOV lsmayil MAMMADOV 2 Azerbaijan Culture Sprats in America t's not a secret that the huge number of people during the period of social instability of the last decade of XX 3century in the territory of Azerbaijan appeared to be cut from their homeland. Those people-Azerbaijanis, Russians, Jews or identifying themselves with Azerbaijan by birth or anyhow suffered the tragic breach with Azerbaijan culture. Eventually creating Diaspora, though not yet completed, these people have a tendency to stay as close as possible to Azerbaijan and they are panicky afraid of assimilation. It is known that Azer baijan Diaspora, no matter of what national origin, when among strangers, wittingly tries to live in a way they used to live before. Diaspora becomes not only a way of physical survival, but also a certain cultural currier of spiritual mission, which includes the tendency to keep values and traditions of the Azerbaijan culture and continue their creative life for the sake of spiritual progress of their homeland independently of its members' intentions: wheth er they should've stay forever or leave. -

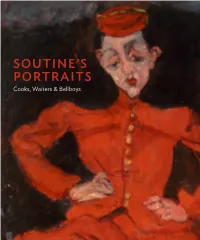

Soutine's Portraits

SOUTINE’S PORTRAITS Cooks, Waiters & Bellboys SOUTINE’S PORTRAITS Cooks, Waiters & Bellboys –– 2 SOUTINE’S PORTRAITS Cooks, Waiters & Bellboys edited by Karen Serres and Barnaby Wright contributors Merlin James, Karen Serres and Barnaby Wright the courtauld gallery in association with paul holberton publishing First published to accompany the exhibition SOUTINE’S PORTRAITS Cooks, Waiters & Bellboys The Courtauld Gallery, London 19 October 2017 – 21 January 2018 The Courtauld Gallery is supported by the Higher Education Funding Council for England (hefce) Copyright © 2017 Texts copyright © the authors All rights reserved. No part of this publicatioan may be transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording or any storage or retrieval system, without the prior permission in writing from the copyright holder and publisher. isbn 978-1-911300-21-2 British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Produced by Paul Holberton Publishing 89 Borough High Street, London se1 1nl www.paulholberton.com Designed by Laura Parker Printing by e-Graphic Spa, Verona Front cover: detail of cat. 8 Back cover: detail of cat. 4 Frontispiece: detail of cat. 4 contents 7 Foreword 8 Exhibition Supporters 9 Samuel Courtauld Society 10 Acknowledgements 14 Introduction Soutine’s Misfits barnaby wright 46 Modern Workers Soutine’s Sitters in Context karen serres 72 Matière and Métier Soutine’s The Little Pastry Cook and Other Personae merlin james 94 CATALOGUE karen serres and barnaby wright 148 Bibliography 152 Photographic Credits Chaïm Soutine (1893–1943) foreword Although I can claim no credit for this wonderful important works in their care. -

André Salmon, Pablo Picasso and the History of Cubism

André Salmon, Pablo Picasso and the History of Cubism André Salmon met Pablo Picasso at the very end of the Spanish artist’s Blue Period (late 1904-early 1905) through their mutual friend the Spanish sculptor Manuel Hugué (known as Manolo). The poet was led to the painter’s studio in a ramshackle building nicknamed the « Bateau Lavoir » at 13 rue Ravignan in Montmartre. The following afternoon Salmon met the poet Max Jacob as they both arrived to pay Picasso a visit. By then Salmon knew the poet Guillaume Apollinaire for almost two years. Apollinaire would meet Picasso shortly afterwards during the winter of 1905. These four men formed the symbiotic relationship known among their peers as « la bande à Picasso ». Salmon and Picasso The significant role these men played in each other lives cannot be overestimated, particularly the friendship between Salmon and Picasso ; for Salmon not only reviewed Picasso’s exhibitions but also inserted incidental references to Picasso’s current activities into his newspaper columns on art. These brief remarks now provide invaluable biographical information which has helped date several of Picasso’s Cubist works. Moreover, from his earliest descriptions of Picasso to his celebrated memoirs, Salmon helped to construct the artist’s reputation as he championed all Picasso’s avant-garde endeavors, regardless of their shockvalue. Most notably, Salmon was the first to praise Les Demoiselles d’Avignon (1907) in his first book on art, La Jeune Peinture française (1912). Although Salmon’s first review of a Picasso exhibition at Ambroise Vollard’s gallery in December 1910 introduces his Paris-Journal readership to the Malaguenian, his short paragraph about a visit to Picasso’s studio at 11 boulevard de Clichy, published on 21 September 1911 tells us more. -

Drawings from the Kröller-Müller National Museum, Otterlo Edited by William S

Drawings from the Kröller-Müller National Museum, Otterlo Edited by William S. Lieberman Author Lieberman, William S. (William Slattery), 1924-2005 Date 1973 Publisher The Museum of Modern Art ISBN 0870702971 Exhibition URL www.moma.org/calendar/exhibitions/2541 The Museum of Modern Art's exhibition history— from our founding in 1929 to the present—is available online. It includes exhibition catalogues, primary documents, installation views, and an index of participating artists. MoMA © 2017 The Museum of Modern Art DRAWINGS FROM THE KROLLER-MULLER NATIONAL MUSEUM, OTTERLO DRAWINGS FROM THE KROLLER-MULLER NATIONAL MUSEUM, OTTERLO van Gogh: Man with a Pipe. 1882. Lithographic crayon and pencil, heightened with gouache, ij}4 x 10% inches DRAWINGS FROM THE KROLLER-MULLER NATIONAL MUSEUM, OTTERLO Edited by William S. Lieberman The Museum of Modern Art, New York Copyright © 1973 by The Museum of Modern Art All rights reserved The Museum of Modern Art 11 West 53 Street New York, New York 10019 Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 72-95074 isbn: 0-87070-297-1 Designed by James Wageman Printed in the United States of America COVER van Gogh: Cypresses with Two Women. 1889. Reed pen and ink, chalk, and touches of oil, 12^x9^ inches SCHEDULE This catalogue is published in conjunction with an exhibition sponsored by OF THE the Netherlands Ministry of Cultural Affairs, Recreation, and Social Welfare EXHIBITION and shown in the United States and Canada under the auspices of The Inter national Council of The Museum of Modern Art. The Museum of Modern Art, New York May 24-August 19, 1973 The Art Institute of Chicago September 8-October 21, 1973 The National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa November 9, 1973-January 1, 1974 Marion Koogler McNay Art Institute, January 13-March 3, 1974 San Antonio CONTENTS 6 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS 7 FOREWORD by Rudolf W. -

Agency and Experience

AGENCY AND EXPERIENCE nonsite.org is an online, open access, peer-reviewed quarterly journal of scholarship in the arts and humanities 5 affiliated with Emory College of Arts and Sciences. 2014 all rights reserved. ISSN 2164-1668 EDITORIAL BOARD Bridget Alsdorf Ruth Leys James Welling Jennifer Ashton Walter Benn Michaels Todd Cronan Charles Palermo Lisa Chinn, editorial assistant Rachael DeLue Robert Pippin Michael Fried Adolph Reed, Jr. Oren Izenberg Victoria H.F. Scott Brian Kane Kenneth Warren SUBMISSIONS ARTICLES: SUBMISSION PROCEDURE Please direct all Letters to the Editors, Comments on Articles and Posts, Questions about Submissions to [email protected]. Potential contributors should send submissions electronically via nonsite.submishmash.com/Submit. Applicants for the B-Side Modernism/Danowski Library Fellowship should consult the full proposal guidelines before submitting their applications directly to the nonsite.org submission manager. Please include a title page with the author’s name, title and current affiliation, plus an up-to-date e-mail address to which edited text and correspondence will be sent. Please also provide an abstract of 100-150 words and up to five keywords or tags for searching online (preferably not words already used in the title). Please do not submit a manuscript that is under consideration elsewhere. ARTICLES: MANUSCRIPT FORMAT Accepted essays should be submitted as Microsoft Word documents (either .doc or .rtf), although .pdf documents are acceptable for initial submissions.. Double-space manuscripts throughout; include page numbers and one-inch margins. All notes should be formatted as endnotes. 1 Style and format should be consistent with The Chicago Manual of Style, 15th ed. -

A Finding Aid to the Richard York Gallery Records, Circa 1865-2005, Bulk 1981-2004, in the Archives of American Art

A Finding Aid to the Richard York Gallery Records, circa 1865-2005, bulk 1981-2004, in the Archives of American Art Sarah Haug Funding for the processing of this collection was provided by Smithsonian Institution's Collections Care Fund March 15, 2011 Archives of American Art 750 9th Street, NW Victor Building, Suite 2200 Washington, D.C. 20001 https://www.aaa.si.edu/services/questions https://www.aaa.si.edu/ Table of Contents Collection Overview ........................................................................................................ 1 Administrative Information .............................................................................................. 1 Historical Note.................................................................................................................. 2 Scope and Content Note................................................................................................. 2 Arrangement..................................................................................................................... 3 Names and Subjects ...................................................................................................... 3 Container Listing ............................................................................................................. 5 Series 1: Correspondence, 1975-2005.................................................................... 5 Series 2: Artists' Artwork Files, circa 1865-2004................................................... 10 Series 3: Client Files, 1965,