Doom Bar Viewpoint

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gin & Tonic Cocktails

DRINKS BOUTIQUE HOTEL, RESTAURANT & BAR Organically grown from humble beginnings GIN & TONIC Tarquins Cornish Dry Gin Cornwall 6.75 Distilled in Wadebridge, incredibly fresh and delicate. Garnished with pink grapefruit and Fever Tree Mediterranean Tonic water. Tarquins Blackberry Gin Cornwall 7.05 Delicately sweet Cornish Gin, infused with blackberries and Cornish wildflower honey. Served with Fever Tree Lemon Tonic water. Tanqueray Gin London 6.15 A classic, London dry gin. Smooth with notes of citrus and juniper. Served with Fever Tree Tonic water and fresh lime. Hendricks Gin Scotland 6.45 Made from juniper, cubeb berries, chamomile, angelica, orange peel and an infusion of cucumber and rose petal. Garnished with cucumber and served with Fever Tree Elderflower Tonic water. Malfy Blood Orange Gin Italy 7.00 Distilled in Italy with Italian oranges, Sicilian blood oranges and juniper. Served with Fever Tree Mediterranean Tonic Water. Jynevra Rhubarb & Vanilla Gin Cornwall 7.05 Wonderfully rich and slightly tart. Served with fresh lime and Fever Tree Mediterranean Tonic water. Tarquins The Sea Dog Navy Strength Gin Cornwall 7.70 Bottled at 57% ABV! Made from 12 different botanicals sourced locally and from distant and exotic locations around the world. Garnished with orange and served with Fever Tree Mediterranean Tonic water. Salcombe Gin Devon 7.30 Distilled to the exacting one-shot London Dry method, this classic citrus led gin is elegantly smooth, distinct and complex yet extremely versatile. Served with Fever Tree Tonic water, garnished with juniper berries. Seedlip Spiced Non Alcoholic Gin England 6.95 A non-alcoholic spirit made from carefully selected botanicals. -

St Ives Real Ale Pub Guide

St Ives Real Ale Guide 1 Sloop Inn The Wharf, TR26 1LP (01736) 796584 Open 11-11 Sun 12-10.30 St Ives oldest pub. Serving Sharp’s Doom Bar and 2 other ales. Seafood Menu Of Town Centre Pubs 2 Rum & Crab Shack Wharf Road, TR26 1LG (01736) 796584 Open 12-11 Fri-Sat 12-12 Waterfront themed bar. Up to 3 ales from Cornish microbreweries. Crab menu. Every effort has been made to ensure that the 3 Lifeboat inn Wharf Road, TR26 1LF (01736) 794123 Open 11-11 information in this guide is correct. St Austell pub with harbourside views. 3 Regular St Austell ales. Live Music. The Cornwall Campaign for Real Ale cannot 4 Union Inn Fore Street, TR26 1AB accept responsibility for errors or inaccuracies. (01736) 796486 Open 11-12 Sun 12-11 Inclusion in this guide does not guarantee Small friendly character pub. Sharp’s Doom Bar & Skinner Betty Stogs. beer quality. 5 Castle Inn Fore Street, TR26 1AB Please Drink Responsibly. (01736) 796833 Open 11-11 Winter 12 –11 Sun 12-11 Friendly town centre pub Est. 1841. Up to 6 ales in summer and real cider. 6 Queen’s Hotel High Street, TR26 1RR (01736) 796468 Open 11-11 Sun 12-10.30 Large modern St Austell bar. Serving St Austell ales. Live music at weekends. 7 Golden Lion High Street, TR26 1RS (01736) 793679 Open 11-11 A thriving locals pub. Skinner’s Betty Stogs, 3 guest ales & real cider. Live music. 8 Sheaf of Wheat Chapel Street, TR26 2LR (01736) 797130 Open 9-12 Winter 11-12 Roomy St Austell pub, popular with tourists and locals. -

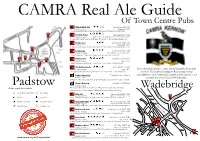

Padstow and Wadebridge Real Ale Pub Guide

CAMRA Real Ale Guide Of Town Centre Pubs 1 Shipwrights Inn North Quay, Pl28 8AF (01841) 532451 Open daily 11-11. Wooden panelled harbourside bar and restaurant. Serving 3 St Austell ales. 2 Old Ship Hotel Mill Square, PL28 8AE (01841) 532357 10.30-11 Sun 10-10.30 Summer 10-11.30 Sun 10-11 Comfortable family run hotel. Regular live music. 3 ales including Brain’s SA. 3 Golden Lion Lanadwell St, PL28 8AN (01841) 532797 Open daily 11-11 Padstow’s oldest pub, home of the Red ‘oss. Doom Bar, Betty Stogs & guest ale. 4 London Inn Lanadwell St, PL28 8AN (01841) 532554 Open daily 11-11.30 Sun 12-11 Welcoming and friendly cosy village local. Serving 5 St Austell ales. 5 Harbour Inn Strand Street, PL28 8BU (01841) 532575 Open 11-11 Small Fisherman’s pub home of the .Peace ‘oss. Serving 3 St Austell ales. Old Custom House South Quay, PL28 8BL 6 Every effort has been made to ensure that the information in this guide (01841) 532359 Open 10-11 The bistro style spacious original Custom. & Excise house. 4 St Austell ales. is correct. The Cornwall Campaign for Real Ale cannot accept responsibility for errors or inaccuracies. Inclusion in this guide does not A Padstow Brewery Established 2013. Padstow (01841) 532169 guarantee beer quality. Please Drink Responsibly. 5 Regular Ales. Pilot, Pale, IPA, Pride & Mayday. Tours & brewing day available. B Sharp’s Brewery Established 1994. Rock Padstow (01208) 862121 Guide to pub list symbols: The largest brewer in the south west. 5 Regular ales, craft cider and many Wadebridge specials. -

CASK-CONDITIONED to Place Your Order Please Call 0845 345 1076

CORNWALL To place your order please call 0845 345 1076 CASK-CONDITIONED www.lwc-drinks.co.uk BEER LWC Cornwall · Wilson Way · Pool Industrial Estate · Redruth · Cornwall · TR15 3JD CORNWALL Who We Are and What We Do Cornwall Depot LWC Cornwall · Wilson Way · Pool Industrial Estate · Redruth · Cornwall · TR15 3JD Service Product Knowledge LWC was established in 1979 and is the fastest-growing privately owned drinks company in the UK. With over 7000 different product lines and over 6000 on-trade customers, we provide the broadest range and greatest service available in the UK drinks industry. With our fantastic support services we provide our customers with a higher-quality experience and enable them to maximise their sales. Over 100 Account Managers are dedicated to bolstering your business potential whilst also eradicating any issues you may face. What makes us different, you ask? Well, there are a few things, really. We have zero listing fees, giving us complete impartiality and helping to increase the depth of our range. We are also 100% demand driven: we only buy on behalf of our customers in relation to their needs and are able to provide the best balance of price, range and service. As an independent company, we're able to act quickly and decisively, a benefit mirrored in our depots, all of which are empowered to make their own decisions, meaning you can get what you want, when you want it. Speaking of 'when you want it', one of the biggest differences from our competitors is that we offer same day delivery*, seven days a week. -

The Perfect Weekendin

the PerfeCt weekend T he perfect weekend in... PADSTOW the route: Padstow, Newquay, Rock village, River Camel, Port Isaac, Port Gaverne Fresh fish and fishermen fill the award-winning the waters around Newquay Padstow lifeboat house In quiet summer weather the north Cornish coast is a boating Saturday afternoon paradise few of us from the English Channel ever experience. Within two hours of HW you can nudge into Newquay just for a 2 Saturday afternoon Spectacular cliffs, long sandy beaches and picturesque fishing look-see, its traditional seaside houses perched above the harbour harbours create a nostalgic atmosphere of long summer hols far from beach. With luck you might stop briefly alongside the quay to buy fish metropolitan clamour. Time turns slowly as the tide uncovers rocky and chips for lunch. Then move out to a splendid anchorage known pools or creeps up old stone breakwaters. Yet there are also pockets of as The Gazzle, with stunning views past Watergate Bay whose wide chic – Newquay is one of Europe’s finest surfing centres and Padstow sands give such exhilarating surfing runs. a Mecca of seafood excellence. What better place to start a perfect Cruising back north in the afternoon, tuck around Trevose Head to weekend than Padstow’s charming locked basin, with lively bistros anchor in Polventon Bay near the dramatic modern lifeboat house. and salty pubs all around. Here you can swim in clear water over a sandy bottom. Soon after half-flood enter the Camel again, anchoring in the river if the weather Saturday MornInG is quiet, either off St George’s Cove or further up in the Pool. -

Jack Clemo 1916-55: the Rise and Fall of the 'Clay Phoenix'

1 Jack Clemo 1916-55: The Rise and Fall of the ‘Clay Phoenix’ Submitted by Luke Thompson to the University of Exeter as a thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English In September 2015 This thesis is available for Library use on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement. I certify that all material in this thesis which is not my own work has been identified and that no material has previously been submitted and approved for the award of a degree by this or any other University. Signature: ………………………………………………………….. 2 Abstract Jack Clemo was a poet, novelist, autobiographer, short story writer and Christian witness, whose life spanned much of the twentieth century (1916- 1994). He composed some of the most extraordinary landscape poetry of the twentieth century, much of it set in his native China Clay mining region around St Austell in Cornwall, where he lived for the majority of his life. Clemo’s upbringing was one of privation and poverty and he was famously deaf and blind for much of his adult life. In spite of Clemo’s popularity as a poet, there has been very little written about him, and his confessional self-interpretation in his autobiographical works has remained unchallenged. This thesis looks at Clemo’s life and writing until the mid-1950s, holding the vast, newly available and (to date) unstudied archive of manuscripts up against the published material and exploring the contrary narratives of progressive disease and literary development and success. -

Mains Sides Starters Puddings

Welcome to We love to host parties — big or small — The Point at Polzeath from birthday celebrations to weddings. Please ask one of our team for our sample Restaurant & Bar menus. Don’t forget to leave us with your We are proud to be a Cornish business feedback at the end of the meal on that celebrates local Cornish food and our comment cards, together with your produce. We are passionate about contact details so we can keep you up providing fresh food at affordable prices. to date with the latest news and offers. STARTERS BREAKFAST Soup of the day (v) 3.95 ½ or 1 pint 8am - 11am Crispy crispy squid, homemade of Atlantic prawns 6.95 / 12.95 Selection of croissants garlic mayonnaise 5.95 Chicken liver parfait, red onion and pastries from 1.95 Mixed mushrooms with lemon and chutney and granary toast 5.95 Thick cut toast, thyme on wholegrain toast (v) 5.95 Smashed peo and broadbean butter and jam 2.50 Port Isaac crab and leek tart 6.95 bruschetta, with olive oil (v) 4.95 Outdoor reared bacon bap 3.50 MAINS Bacon and Doom Bar battered Slow roasted pork belly with a honey free-range egg bap 3.95 and mustard sauce, mashed potato fish and chips 9.95 Pork sausage and seasonal vegetables 11.95 Grilled fish of the day market price and onion bap 3.95 Newlyn landed fish pie with Porthilly mussels in a Cornish Orchard Yoghurt with home made mash and cheesy breadcrumb Cider broth with chips 8.95 granola 3.50 topping 10.50 6oz beef burger served with home Fruit salad with yoghurt 3.50 Courgette, pinenut and lemon made coleslaw, caramelised linguine -

BIC-1954.Pdf

CONTENTS PAGE Preamble ... ... ... ... ... ... 3 The Weather of 1954 ... ... ... ... ... 4 List of Contributors ... ... ... ... ... 6 Cornish Notes ... ... ... ... ... ... 8 Recoveries of Ringed Birds ... ... ... ... 26 Arrival and Departure of Cornish-breeding Migrants ... 26 The Walmsley Sanctuary and Camel Estuary ... ... 28 The Isles of Scilly ... ... ... ... ... 30 Arrival and Departure of Migrants in the Isles of Scilly ... 35 The Tamar Lake ... ... ... ... ... 36 The Macmillan Library ... ... ... ... ... 38 The Society's Rules ... ... ... ... ... 39 Balance Sheet ... ... ... ... ... ... 40 List of Members for 1954 ... ... ... ... 41 Committee for 1954 ... ... ... ... ... 53 Index ... ... ... ... ... ... ... 54 TWENTY-FOURTH REPORT OP The Cornwall Bird Watching and Preservation Society 1954 Edited by B. H. RYVES, H. M. QUICK and A. G. PARSONS (kindly assisted by Dr. R. H. BLAIR) Forty-nine new members joined the Society during 1954. We regret the loss by death of seven members; thirteen have resigned, and the resignation of twelve more assumed by reason of non payment of subscription. This makes the total of ordinary mem bers 607. Mr. Hayman (M.P. for Camborne-Falmouth) was elected an Honorary member at the Annual Meeting, in recognition of his services during the passage through Parliament of the Bird Protec tion Act. The Twenty-third Annual Meeting was held in the Museum, Truro, on May 1st. Mr. Hurrell showed his films of Birds of Prey at the nest, and of Flamingoes in the Camargue. At the Autumn meeting on November 6th, Mr. Parsons spoke of his visit to Swedish Lapland, showing some of his own films and photographs. One Executive Committee meeting was held during the year. Our thanks are due to Mr. S. F. -

Seascape Character Assessment Report

Seascape Character Assessment for the South West Inshore and Offshore marine plan areas MMO 1134: Seascape Character Assessment for the South West Inshore and Offshore marine plan areas September 2018 Report prepared by: Land Use Consultants (LUC) Project funded by: European Maritime Fisheries Fund (ENG1595) and the Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs Version Author Note 0.1 Sally First draft desk-based report completed May 2016 Marshall Maria Grant 1.0 Sally Updated draft final report following stakeholder Marshall/ consultation, August 2018 Kate Ahern 1.1 Chris MMO Comments Graham, David Hutchinson 2.0 Kate Ahern Final Report, September 2018 2.1 Chris Independent QA Sweeting © Marine Management Organisation 2018 You may use and re-use the information featured on this website (not including logos) free of charge in any format or medium, under the terms of the Open Government Licence. Visit www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/doc/open-government- licence/ to view the licence or write to: Information Policy Team The National Archives Kew London TW9 4DU Email: [email protected] Information about this publication and further copies are available from: Marine Management Organisation Lancaster House Hampshire Court Newcastle upon Tyne NE4 7YH Tel: 0300 123 1032 Email: [email protected] Website: www.gov.uk/mmo Disclaimer This report contributes to the Marine Management Organisation (MMO) evidence base which is a resource developed through a large range of research activity and methods carried out by both MMO and external experts. The opinions expressed in this report do not necessarily reflect the views of MMO nor are they intended to indicate how MMO will act on a given set of facts or signify any preference for one research activity or method over another. -

Padstow and Stepper Point Boom That Tells of Caves in Nearest Toilet: Rock Quarry Car Park and South Quay, the Rock Below Your Feet

The daymark tower was along this part of the coast Walks on and around the built, probably in the early were formed in this way; nineteenth century, as a and at Roundhole Point, to maritime navigational aid, the south of this walk, there designed to guide sailors is a tremendous example Olver Photo: Lucy Photo: Julie Horsley into the River Camel. of this. Note the other dramatic rock formations From flint tools found on caused by the wave in North Cornwall the headland it appears erosion here too. that people lived in this part of Stepper Point as far Leave the Coast Path here, Photo: Seb Loram back as 6000 years ago, forking left to the track and possibly even earlier. ahead and turning right on this track, following it Carry on along the around to the left shortly Coast Path as it heads afterwards to join the road south above the sea, at Lellizick. Wildlife: There is plenty of wildlife to see around North dropping downhill, until Cornwall including, Turnstones, Red Admirals and Peregrine you come to the place Turn right on the road Falcons. where it turns sharply left and then pick up the track Other Useful Information around a rocky cove. on your left a moment Photo: Lindsay Philip later, which will lead you Nearest Refreshments: There are numerous restaurants, As you walk along here quickly back to (3), at pubs, teashops and takeaways in Padstow. you will hear the hollow Harbour Cove Padstow and Stepper Point boom that tells of caves in Nearest toilet: Rock Quarry Car Park and South Quay, the rock below your feet. -

The History of NCI Stepper Point

The History of NCI Stepper Point Stepper Point stands high on the north coast of Cornwall. Along with Pentire Point opposite, it guards the entrance to the Camel estuary and the port of Padstow. The lookout commands a spectacular view north to the open sea and Lundy Island, 36 nautical miles away and visible with binoculars on a clear day, west to Trevose lighthouse and the new lifeboat station, taking in the full sweep of the river down to Padstow in the south, and the beaches of Rock, Daymer Bay and Polzeath to the east. At low water the sand of the 'Doom Bar', destroyer of many ships and crew over the centuries, is visible below Stepper and the quarry. The rocks of Greenaway can still prove hazardous to gale- blown vessels. ABOUT OUR STATION The present lookout at Stepper Point was built in the early 1920s to keep a watching brief over the approaches to Padstow and the Camel Estuary with its notorious Doom Bar. The Doom Bar, a huge sandbank extending from Hawkers Cove eastwards to within about 200 yards of Greenaway Rocks and Daymer Bay, has been a hazard to shipping entering the port since time beyond record. In the period 1800 to the early 1900s records show that over two hundred ships have come to grief in this area, needless to say many lives have been lost, not least amongst them many local men who have served on lifeboats stationed at Hawkers Cove. The "Mariners Friend", one of the earliest lifeboats in the British Isles, was stationed at Hawkers Cove in 1823; this was paid for by local townsfolk who were all too aware of the dangers. -

PDZ: 14 Camel Estuary (Stepper Point to Pentire Point)

PDZ: 14 Camel Estuary (Stepper Point Management Area 35 to Pentire Point) Management Area 36 Camel Estuary (Stepper Point to Pentire Point) This area is valued for its natural beauty, with the calm estuary environment contrasting with the small section of rugged open coast at Stepper Point and Pentire Point. Most of this area faces north and is slightly less exposed to the dominant westerly Atlantic conditions that occur more to the south-west. The area is generally rural and undeveloped including within the estuarine area, however a number of significant communities are sited towards the estuary mouth at Padstow and Rock, on the open coast at Polzeath and inland towards the estuary tidal limit at Wadebridge and Sladesbridge. Cornwall and Isles of Scilly SMP2 Final Report Chapter 4 PDZ14 1 February 2011 Cornwall and Isles of Scilly SMP2 Final Report Chapter 4 PDZ14 2 February 2011 General Description Built Environment Agriculture the major land use, with fisheries still significant at Padstow and within the estuary with a designated shell fishery. Padstow retains an active harbour and small fishing fleet. There are a significant number of fixed assets present related to the communities which include flood and coastal defences, commercial and residential properties, sewage treatment works, roads, harbour and sailing infrastructure and other A39 viaduct over the Camel at amenity features such as the Camel Trail. Wadebridge Heritage There are a number of Scheduled Monuments in the area including a churchyard cross in St Michael’s Church. There are numerous Bronze Age barrows on the coastal strip. There is a submerged forest at Daymer Bay, and an important coastguard complex at Hawkers Cove, Padstow harbour.