'Like an American, but Without a Gun'?: Canadian National Identity

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

90S TV Superbonus

America’s Favorite TV Shows (America has bad taste) Friends Which character had a twin? Phoebe Which of the friends dated Rachel? Ross, Joey Who of the following did not guest star on the show? Circle your answers. Ralph Lauren Winona Ryder Sarah Jessica Parker Ben Stiller RuPaul Brad Pitt Why did Ross get divorced from his first wife? She is a lesbian Where does Phoebe’s boyfriend David move to in the first season? Minsk Who was Rachel’s prom date? Chip On which daytime drama does Joey star as Dr. Drake Remoray? Days of our Lives Why is Joey written out of the daytime drama? He says in an interview he writes his own lines At which job does Monica have to wear fake breasts? The 50s diner Who does Rachel convince to shave their head? Bonnie, Ross’s girlfriend In one episode, Joey buys a pet chick. What does Chandler buy? A duck Who plays Phoebe’s half-brother Frank? Giovani Ribisi What favor does Phoebe do for Frank and his wife Alice? She is a surrogate mother for triplets What other tv show that started in the 90s did the actress playing Alice star on? That 70s Show When Joey and Chandler switch apartments with Monica and Rachel, what do Rachel and Monica offer to get their apartment back? Season tickets to the Knicks In Season 5, whose apartment does Ross move into? Ugly Naked Guy Who is first to figure out that Chandler and Monica are dating? Joey Who gets married in Las Vegas? Ross and Rachel Who plays Rachel’s sister Jill? Reese Witherspoon What causes the fire in Rachel and Phoebe’s apartment? Rachel’s hair straightener -

Press Kit Falling Angels

Falling Angels A film by Scott Smith Based on the novel by Barbara Gowdy With Miranda Richardson Callum Keith Rennie Katherine Isabelle RT : 101 minutes 1 Short Synopsis It is 1969 and seventeen year old Lou Field and her sisters are ready for change. Tired of enduring kiddie games to humour a Dad desperate for the occasional shred of family normalcy, the Field house is a place where their Mom’s semi-catatonic state is the result of a tragic event years before they were born. But as the autumn unfolds, life is about to take a turn. This is the year that Lou and her sisters are torn between the lure of the world outside and the claustrophobic world of the Field house that can no longer contain the girls’ restless adolescence. A story of a calamitous family trying to function, Falling Angels is a story populated by beautiful youthful rebels and ill-equipped parents coping with the draw of a world in turmoil beyond the boundaries of home and a manicured lawn. 2 Long Synopsis Treading the fine line between adolescence and adulthood, the Field sisters have all but declared war on their domineering father. Though Jim Field (Genie and Gemini winner Callum Keith Rennie ) runs the family house like a military camp, it’s the three teenaged daughters who really run the show and baby-sit their fragile mother Mary, (Two-time Oscar ® nominee Miranda Richardson) as she quietly sits on the couch and quells her anxiety with whiskey. It’s 1969 and beneath suburbia’s veneer of manicured lawns and rows of bungalows, the world faces explosive social change. -

Film Reference Guide

REFERENCE GUIDE THIS LIST IS FOR YOUR REFERENCE ONLY. WE CANNOT PROVIDE DVDs OF THESE FILMS, AS THEY ARE NOT PART OF OUR OFFICIAL PROGRAMME. HOWEVER, WE HOPE YOU’LL EXPLORE THESE PAGES AND CHECK THEM OUT ON YOUR OWN. DRAMA 1:54 AVOIR 16 ANS / TO BE SIXTEEN 2016 / Director-Writer: Yan England / 106 min / 1979 / Director: Jean Pierre Lefebvre / Writers: Claude French / 14A Paquette, Jean Pierre Lefebvre / 125 min / French / NR Tim (Antoine Olivier Pilon) is a smart and athletic 16-year- An austere and moving study of youthful dissent and old dealing with personal tragedy and a school bully in this institutional repression told from the point of view of a honest coming-of-age sports movie from actor-turned- rebellious 16-year-old (Yves Benoît). filmmaker England. Also starring Sophie Nélisse. BACKROADS (BEARWALKER) 1:54 ACROSS THE LINE 2000 / Director-Writer: Shirley Cheechoo / 83 min / 2016 / Director: Director X / Writer: Floyd Kane / 87 min / English / NR English / 14A On a fictional Canadian reserve, a mysterious evil known as A hockey player in Atlantic Canada considers going pro, but “the Bearwalker” begins stalking the community. Meanwhile, the colour of his skin and the racial strife in his community police prejudice and racial injustice strike fear in the hearts become a sticking point for his hopes and dreams. Starring of four sisters. Stephan James, Sarah Jeffery and Shamier Anderson. BEEBA BOYS ACT OF THE HEART 2015 / Director-Writer: Deepa Mehta / 103 min / 1970 / Director-Writer: Paul Almond / 103 min / English / 14A English / PG Gang violence and a maelstrom of crime rock Vancouver ADORATION A deeply religious woman’s piety is tested when a in this flashy, dangerous thriller about the Indo-Canadian charismatic Augustinian monk becomes the guest underworld. -

Getting a on Transmedia

® A PUBLICATION OF BRUNICO COMMUNICATIONS LTD. SPRING 2014 Getting a STATE OF SYN MAKES THE LEAP GRIon transmediaP + NEW RIVALRIES AT THE CSAs MUCH TURNS 30 | EXIT INTERVIEW: TOM PERLMUTTER | ACCT’S BIG BIRTHDAY PB.24462.CMPA.Ad.indd 1 2014-02-05 1:17 PM SPRING 2014 table of contents Behind-the-scenes on-set of Global’s new drama series Remedy with Dillon Casey shooting on location in Hamilton, ON (Photo: Jan Thijs) 8 Upfront 26 Unconventional and on the rise 34 Cultivating cult Brilliant biz ideas, Fort McMoney, Blue Changing media trends drive new rivalries How superfans build buzz and drive Ant’s Vanessa Case, and an exit interview at the 2014 CSAs international appeal for TV series with the NFB’s Tom Perlmutter 28 Indie and Indigenous 36 (Still) intimate & interactive 20 Transmedia: Bloody good business? Aboriginal-created content’s big year at A look back at MuchMusic’s three Canadian producers and mediacos are the Canadian Screen Awards decades of innovation building business strategies around multi- platform entertainment 30 Best picture, better box offi ce? 40 The ACCT celebrates its legacy Do the new CSA fi lm guidelines affect A tribute to the Academy of Canadian 24 Synful business marketing impact? Cinema and Television and 65 years of Going inside Smokebomb’s new Canadian screen achievements transmedia property State of Syn 32 The awards effect From books to music to TV and fi lm, 46 The Back Page a look at what cultural awards Got an idea for a transmedia project? mean for the business bottom line Arcana’s Sean Patrick O’Reilly charts a course for success Cover note: This issue’s cover features Smokebomb Entertainment’s State of Syn. -

Mongrel Media Presents

Mongrel Media Presents Language: English Distribution Publicity Bonne Smith Star PR 1028 Queen Street West Tel: 416-488-4436 Toronto, Ontario, Canada, M6J 1H6 Fax: 416-488-8438 Tel: 416-516-9775 Fax: 416-516-0651 E-mail: [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] www.mongrelmedia.com High res stills may be downloaded from http://www.mongrelmedia.com/preggoland LOGLINE A 35 year-old woman pretends to be pregnant to fit in with her friends. SHORT SYNOPSIS When 35-year-old Ruth ruins a baby shower with her juvenile antics, her old high school cronies- who are all mothers now-promptly de-friend her. But when she is later mistakenly thought to be ‘with child’ she is inexplicably welcomed back into the group. Although she initially tries to come clean, the many perks of pregnancy are far too seductive to ignore. Preggoland is a comedy about our societal obsession with babies and the lengths we’ll go to be part of a club. SYNOPSIS At 35, Ruth (Sonja Bennett) hasn’t changed much since high school. She’s still partying in parking lots, working as a cashier in a supermarket, and living in her father’s basement. When Ruth gets drunk at a friend’s baby shower and ruins it with her juvenile antics, her old high school cronies – who are now all married with children – suggest she might want to find some friends her own mental age. Ruth is devastated. Just when Ruth hits rock bottom, she runs into her friends who mistakenly think she’s pregnant. -

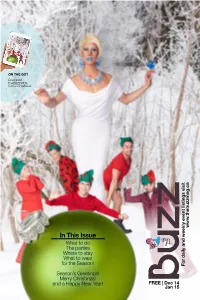

In This Issue What to Do the Parties Where to Stay What to Wear

ON THE GO? Download theBUZZ PDF from our website www.thebuzzmag.ca In This Issue What to do The parties Where to stay What to wear for the Season! For daily and weekly event listings visit Season’s Greetings! Merry Christmas! and a Happy New Year! FREE | Dec 14 Jan 15 THE ARTISTS HAVE CHECKED IN. At the centre of Toronto’s Art and Design District, the Gladstone Hotel has 37 different artist designed hotel rooms to check in to, 3 gallery spaces dedicated to supporting local Canadian art and a buzzing cultural community for you to check out. WWW.GLADSTONEHOTEL.COM | @GLADSTONEHOTEL 2 December 2014/January 2015 theBUZZmag.ca theBUZZmag.ca December 2014/January 2015 3 Issue #004 DEC 2014 /JAN 2015 VOLUME 4 PRESENTED BY PINKPLAY MAGS Our Cover Models with our Publisher & Creatve Director Antoine Elhashem The Publisher/Creative Director: Antoine Elhashem Editor-in-Chief: Brandon Bent Editor Art Director: Martin Whelan General Manager: Kim Dobie Supervising Art Director: Chris Trubela Sales Reps: Carolyn Burtch, Eric Lahey and Casey Robertson. Assistant to the Editor: Ninsen Lo On the Cover: Winter Wonderland Events Editor: Ninsen Lo, Lara Thompson Regular Columnists: As Pictured from Left to Right: Paul Bellini, Donnaramma, Cat Grant, Boyd Kodak, Owen Sheppard Brandon Bent Yes, we dragged Brandon onto the cover of this sleeping. We will be having a few holiday gatherings at Feature Writers: It is that time of year when we look back on the past issue. He was not expecting it but we couldn’t resist home; filling our heads with laughter, our mouths with Bryen Dunn, Lara Thompson 12 months and also look forward to the New Year. -

The Last Comedy

v*? - at \ The Banff Centre for Continuing Education T h e B a n f f C e n t r e As The Banff Centre embarks on its seventh decade, it carries with it a new image as an internationally renowned centre of creativity. presents The Centre continues to stress the imagina tion's role in a vibrant and prosperous soci ety. It champions artists, business leaders and their gift of creativity. It brings profes The Last sionals face to face with new ideas, catalyses achievement, experiments with disciplinary boundaries. It takes Canadians and others to the cutting edge - and beyond. Comedy The Banff Centre operates under the authority of The Banff Centre Act, Revised by Michael Mackenzie Statutes of Alberta. For more information call: Arts Programs 762-6180 Gallery Information 762-6281 Management Programs 762-6129 Directed by - Jean Asselin Conference Services 762-6204 Set and Costume Design by - Patrick Clark Lighting Design by - Harry Frehner Set and Costume Design Assistant - Julie Fox* Lighting Design Assistant - Susann Hudson* Arts Focus Stage Manager - Winston Morgan+ Our Centre is a place for artists. The Assistant Stage Manager - Jeanne LeSage*+ Banff Centre is dedicated to lifelong Production Assistant - David Fuller * learning and professional career develop ment for artists in all their diversity. * A resident in training in the Theatre Production, We are committed to being a place that Design and Stage Management programs. really works as a catalyst for creative +Appearing through the courtesy of the Canadian activity — a place where artistic practices Actors' Equity Association are broadened and invigorated. There will be one fifteen minute intermission Interaction with a live audience is an important part of many artists’ profession al development. -

Jaskaran Gill

Jaskaran Gill 62 Honeywood Road Toronto, ON M3N 1B2 (647) 521-6720 | [email protected] An enthusiastic and creative screenwriter and independent film producer committed and passionate about telling stories from underrepresented voices. Excellent organization and communication skills; strong budgeting skills to improve productivity and efficiency while cutting costs. Knowledge of film projects from inception to completion. Ability to write and edit scripts. Experience Screenwriter and Producer / The English Teacher – Short Film 2019 – 2020 Currently in post-production Screenwriter and Producer / Losing It All – Short Film 2019 – 2020 Currently in post-production Screenwriter and Producer / A Close Eye – Short Film 2019 – 2020 Official Selection at BronzeLens Film Festival 2020, Rapport Festival 2020, The Life Off Sessions Screenwriter and Producer / Terms of Agreement – Short Film 2018 – 2019 Official Selection at the Toronto International Nollywood Film Festival, Finalist in the 'Best Canadian Short Film' category. Screenwriter and Producer / Affirmative (Re)action – Short Film 2017 – 2018 Official Selection at the Atlanta Comedy Film Festival Education Immigration and Settlement Studies MA / Ryerson University 2019 – PRESENT Write and Sell the Hot Script / Raindance 2016 Taught by Elliot Grove, film producer and founder of the Raindance Film Festival and the British Independent Film Awards. Screenwriting I - Write Your Own Screenplay / George Brown College 2016 Received mentorship from Paul Bellini, writer on The Kids in the Hall and This Hour Has 22 Minutes. Arts and Contemporary Studies Program / Ryerson University 2015 Majored in Global Studies. Achievements Screenwriter / From Far and Wide -Semifinalist, 2019 ScreenCraft Shorts Competition -Quarterfinalist, 2019 WeScreenPlay Shorts Contest . -

Comedy: Stand-Up, Gay Male by Tina Gianoulis Actor and Comic Jason Stuart

Comedy: Stand-Up, Gay Male by Tina Gianoulis Actor and comic Jason Stuart. Encyclopedia Copyright © 2015, glbtq, Inc. Courtesy JasonStuart. Entry Copyright © 2002, glbtq, Inc. com. Reprinted from http://www.glbtq.com Stand-up comedy is a form of entertainment where one performer stands in front of an audience and tries to make common cause with that audience by pointing out the ridiculous and humorous in the universal problems of everyday life. Stand-up comics balance on a fine edge between the funny and the offensive. They can be social critics, prodding audiences to look at the unfairness and inequality in life and to rise above them with a laugh. They can also be part of that unfairness by using humor to make fun of women, gays, and ethnic groups, allowing some members of their audiences to feel superior to those who are the butts of the joke. The dilemma is well expressed by Henry Machtey on the Gay Comedy Links website: "Stand-up comedy. Cracking jokes. Are you going to aim those jokes at people who are less powerful? or people who are more powerful?" Too often, gay men have been the objects of hostile humor. Queer jokes, like female jokes and ethnic jokes, have long been a staple of straight stand-up comics looking for an easy laugh from audiences eager to assert their own heterosexuality in a world where it is often dangerous to be gay. At the same time, however, perhaps long before the all-male Greek theater of the fourth century B.C.E., audiences have also had a fascination with gender-bending. -

Wes Carpenter's Foreign Movies

This Issue’s Extravaganza: Wes Carpenter’s Foreign Movies November/December 2015 • Issue 58 • $10 USD pandamagazine.com From the Editor Issue 57 Completists #AAA Aardvarks (Rich Bragg, Jonathan McCue) • A Seer Who We’ve lost a number of prominent puzzle people this Argues (Adrian, Casey, Catherine, David, Eli, Rob) • Alison year. Henry Hook is one of the constructors, along with Muratore, Audrey Muratore, Eric Suess • J.H. Andersson • Mike Selinker and Patrick Berry, that helped inspire Ben Lowenstein • Black Fedora Group (Herman Chau, Lennart P&A Puzzle Magazine. Their work in Games Magazine Jansson, Nick Wu, Moor Xu, Eric Yu) • Joe Bohanon • Robert and Henry Hook’s $10,000 Trivia Contest gave me the Bosch • Nick Brady • Buzz Lime Pi (Jay Lorch, Jonathan desire to write interconnected puzzle suites. Henry Hook Anderson, Josie Naylor, Michelle Teague, Robb Effinger, Sarah passed away in October at 60, far too young. Caley, Sean McCarthy, Sean Osborn) • Jeremy Conner • Dan Katz, Jackie Anderson, & Steve Katz • Das Zauberboot (Mike, Big thanks to Joe Cabrera for the cover, and for the new Catherine, Dan, Donna, Becky) • DelphiRune (Steve & Anita) cover layout. • Joseph DeVincentis • Martin Doublesin • Doug Orleans & Paula Wing • david edwards • Joe Fendel • Dustin Foley • Foggy Brume Nathan Fung • Lily Geller • GUToL (Angel Bourgoin, Keith Bourgoin, Dan Moren, Evan Ritt) • Mark Halpin • Chris Harris Issue 57 Top Ten • David Harris • Paul Hlebowitsh • Brent Holman • Illegal Phlogizote (Ben Smith, Brie Frame, Joe Cabrera, Jenny Gutbezahl, -

The Twentieth Century / 7:30 Pm the Twentieth Century / 9 Pm

January / February 2020 Canadian & International Features: Canada’s Top Ten Film Festival: CRANKS special Events THE TWENTIETH CABIN FEVER: CENTURY FREE FILMS FOR KIDS! www.winnipegcinematheque.com January 2020 TUESDAY WEDNESDAY THURSDAY FRIDAY SATURDAY SUNDAY 1 2 3 4 5 closed: New Year’s Day Parasite / 7 pm Honeyland / 7 pm Honeyland / 3 pm & 7:30 pm Cabin fever: Honeyland / 9:30 pm Parasite / 9 pm Parasite / 5 pm & 9:15 pm Fantastic Mr. Fox / 3 pm Honeyland / 5 pm Parasite / 7 pm 7 8 9 10 11 12 RESTORATION TUESDAYS: Honeyland / 7 pm UWSA Snowed In: Canada’s Top Ten: Canada’s Top Ten: And the Birds Cabin fever: Quartet / 7 pm Parasite / 9 pm Waves / 7 pm And the Birds Rained Down / 7 pm Rained Down / 2:30 pm Mirai / 3 pm Heater / 9 pm Parasite / 9 pm Honeyland / 9:30 pm Honeyland / 5 pm Canada’s Top Ten: Stages of Beauty: The Short And the Birds Films of Matthew Rankin / 7 pm Rained Down / 5 pm Canada’s Top Ten: The Twentieth Century / 7:30 pm The Twentieth Century / 9 pm 14 15 16 17 18 19 RESTORATION TUESDAYS: Canada’s Top Ten: Hinterland Remixed / 7 pm Cranks / 7 pm Letter from Cabin fever: Heater / 7 pm The Twentieth Century / 7 pm Canada’s Top Ten: Canada’s Top Ten: Masanjia / 3 pm & 7 pm Diary of a Wimpy Kid / 3 pm Quartet / 9 pm Cranks / 9 pm And the Birds The Twentieth Century / 9 pm Cranks / 5 pm Cranks / 5 pm Rained Down / 9 pm Canada’s Top Ten: Canada’s Top Ten: The Twentieth Century / 9 pm The Twentieth Century / 7 pm 21 22 23 24 25 26 RESTORATION TUESDAYS: McDonald at the Movies: Canada’s Top Ten: Canada’s Top Ten: Canada’s -

Tthhheee Tttaaattttttooooo

A9 | Monday, April 11, 2005 The Bristol Press TTHHEE TTAATTTTOOOO BRISTOL PRESS MAKING A PERMANENT IMPRESSION SINCE 1994 VOLUME 11 No. 11 ‘Hollow Men’ fill Iraq War protesters feel lucky By STEVEN DUREL University senior involved with the world, many calling for a and food from various organi- The Tattoo the Progressive Student timetable for the removal of zations. The Tent People even a TV humor void Alliance. American troops from Iraq, a entertained local religious lead- Amidst the ocean of green Marching in front of the nation which now possesses its ers who stopped by to let the By STEFAN KOSKI hats and balloons of St. Capitol at noon, the demon- own multi-ethnic government protesters know that their The Tattoo Patrick’s Day in Hartford last strators chanted and carried and military. Many Coalition efforts were much appreciated. month, there were also banners signs condemning the invasion. countries, most notably Spain, Despite the overall sense of Ever since “Saturday Night Live” premiered on NBC in 1975, a and cries of discontent. Rallying together an hour have removed their forces from solidarity among the anniver- host of other sketch comedy shows have been launched with Gathering around the state later, the protesters denounced Iraq and others, like Italy and sary demonstrations, the pro- mixed success. The most notable of these include Fox’s “Mad TV” Capitol, dozens of dissatisfied the war, making reference to the Ukraine, have recently testers themselves seemed less and Canada’s “The Kids in the Hall.” protesters marked the second the more than 100,000 lives lost made requests to leave the area than optimistic about how the Comedy Central has introduced many of these sketch comedy anniversary of the invasion of in the past two years.