Introduction Preparation – the Six Ps to Going Faster

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ayc Fleets Rise to the Challenge

AUSTIN YACHT CLUB TELLTALE SEPT 2014 AYC FLEETS RISE TO THE CHALLENGE Photo by Bill Records Dave Grogono w/ Millie and Sonia Cover photo by Bill Records IN THIS ISSUE SAVE THE DATE 4th Annual Fleet Challenge Social Committee News Sep 7 Late Summer #1 Oct 18-19 Governor’s Cup Remebering Terry Smith Ray & Sandra’s Sailing Adventure Sep 13-14 Centerboard Regatta Oct 23 AYC Board Mtg Sep 20-21 ASA 101 Keelboat Class Oct 25-26 ASA 101 Keelboat Class Board of Directors Reports Message from the GM Sep 21 Late Summer #2 Oct 25 Women’s Clinic Fleet Captain Updates Scuttlebutt Sep 25 AYC Board Mtg Oct 26 Fall Series #1 Sep 28 Late Summer #3 Nov 2 Fall Series #2 Sailing Director Report Member Columns Oct 5 Late Summer #4 Nov 8-9 TSA Team Race Oct 10 US Sailing Symposium Nov 9 Fall Series #3 Oct 11 US Sailing Race Mngt Nov 16 Fall Series #4 2014 Perpetual Award Nominations Recognize those that have made a difference this year at AYC! You may nominate a whole slate or a single category – the most important thing is to turn in your nominations. Please return this nomination form to the AYC office by mail, fax (512) 266-9804, or by emailing to awards committee chairperson Jan Thompson at [email protected] in addition to the commodore at [email protected] by October 15, 2014. Feel free to include any additional information that is relevant to your nomination. Jimmy B. Card Memorial Trophy: To the club senior sailor, new to the sport. -

Further Devels'nent Ofthe Tunny

FURTHERDEVELS'NENT OF THETUNNY RIG E M H GIFFORDANO C PALNER Gi f ford and P art ners Carlton House Rlngwood Road Hoodl ands SouthamPton S04 2HT UK 360 1, lNTRODUCTION The idea of using a wing sail is not new, indeed the ancient junk rig is essentially a flat plate wing sail. The two essential characteristics are that the sail is stiffened so that ft does not flap in the wind and attached to the mast in an aerodynamically balanced way. These two features give several important advantages over so called 'soft sails' and have resulted in the junk rig being very successful on traditional craft. and modern short handed-cruising yachts. Unfortunately the standard junk rig is not every efficient in an aer odynamic sense, due to the presence of the mast beside the sai 1 and the flat shapewhich results from the numerousstiffening battens. The first of these problems can be overcomeby usi ng a double ski nned sail; effectively two junk sails, one on either side of the mast. This shields the mast from the airflow and improves efficiency, but it still leaves the problem of a flat sail. To obtain the maximumdrive from a sail it must be curved or cambered!, an effect which can produce over 5 more force than from a flat shape. Whilst the per'formanceadvantages of a cambered shape are obvious, the practical way of achieving it are far more elusive. One line of approach is to build the sail from ri gid componentswith articulated joints that allow the camberto be varied Ref 1!. -

Pyc's Dodge Rees Olympic Hopeful

Pensacola Yacht Club February 2011 PYC’S DODGE REES OLYMPIC HOPEFUL STA--NOTES ON THE HORIZON IN FEBRUARY... FLAG OFFICERS :[LWOLU:\JO`.LULYHS4HUHNLY Tuesday, February 1 ALAN MCMILLAN c 449-3101 h 456-6264 Membership Committee – 6pm Commodore [email protected] Prospective Member Night – 7pm JERE ALLEN c 529-0927 h 916-4480 Wednesday, February 2 Vice Commodore/Facilities [email protected] Club Seminar - 7pm EPA/Community Relations Thursday, February 3 SUSAN MCKINNON c 450-0703 h 477-9951 Hospitality Meeting – 12noon Rear Commodore/Membership [email protected] February 4 – 6 Flying Tigers East Coast Championship JOHN BUZIAK c 291-2115 h 457-4142 Fleet Captain/GYA Coordinator [email protected] Saturday, February 5 PYC Mardi Gras Regatta BERNIE KNIGHT c 516-6218 w 995-1452 Tuesday, February 8 Secretary/By-laws [email protected] Junior Board Meeting - 6pm DAN SMITHSON c 449-7843 h 968-1260 Thursday, February 10 Treasurer/Finance [email protected] Entertainment Committee – 5:30pm FL Commodore’s Association – 6:30pm BOARD OF DIRECTORS February 12-13 SAM FOREMAN c 748-0498 h 470-0866 Raft Up at Pirates Cove Commodore Emeritus/ [email protected] Tuesday, February 15 Endowment Fund Ham Radio Club – 7pm LEE HARGROVE c 292-4783 Wednesday, February 16 Marina & Dry Storage [email protected] PYC Board Meeting - 6:30pm FR. JACK GRAY w 452-2341 ex 3116 c 449-5966 Thursday, February 17 Fleet Chaplain [email protected] General Membership Meeting - 6pm CONRAD HAMILTON c 516-0959 h 934-6625 Saturday, February 19 Development [email protected] PYC Board & Flag Officer Meeting - 1pm Thursday, February 24 BRUCE PARTINGTON h 433-7208 Cooking Demo & Wine Pairing - 6:30pm Junior Sailing [email protected] or Reservations“Promoting Required the Finest Homes in [email protected] Florida” COMING UP IN MARCH. -

Survival Rates of Russian Woodcocks

Proceedings of an International Symposium of the Wetlands International Woodcock and Snipe Specialist Group Survival rates of Russian Woodcocks Isabelle Bauthian, Museum national d’histoire naturelle, Centre de recherches sur la biologie des populations d’oiseaux, 55 rue Buffon, 75005 Paris, France. E-mail: [email protected] Ivan Iljinsky, State University of St Petersburg, Russia. E-mail: [email protected] Sergei Fokin, State Informational-Analytical Center of Game Animals and Environment Group. Woodcock, Teterinsky Lane, 18, build. 8, 109004 Moscow, Russia. E-mail: [email protected] Romain Julliard, Museum national d’histoire naturelle, Centre de recherches sur la biologie des populations d’oiseaux, 55 rue Buffon, 75005 Paris, France. E-mail: [email protected] François Gossmann, Office national de la chasse et de la faune sauvage, 53 rue Russeil, 44 000 Nantes, France. E-mail: [email protected] Yves Ferrand, Office national de la chasse et de la faune sauvage, BP 20 - 78612 Le-Perray-en-Yvelines Cedex, France. E-mail: [email protected] We analysed 324 recoveries from 2,817 Russian Woodcocks ringed as adult or yearling in two areas in Russia (Moscow and St Petersburg). We suspected that birds belonging to these two areas may experience different hunting pressure or climatic conditions, and thus exhibit different demographic parameters. To test this hypothesis, we analysed spatial and temporal distribution of recoveries, and performed a ringing-recovery analysis to estimate possible survival differences between these two areas. We used methods developed by Brownie et al. in 1985. We found differences in temporal variations of the age ratio between the two ringing areas. -

What's So Great About Sailing the Gorge?

What’s So Great About Sailing the Gorge? Bill Symes & Jonathan McKee Seattle native Jonathan McKee was one of the early pioneers of dinghy sailing in the Gorge. His accomplishments include two Olympic medals (Flying Dutchman gold in 1984, and 49er bronze in 2000), seven world championships in various classes, and two Americas Cup challenges. CGRA’s Bill Symes caught up with Jonathan to find out why he likes sailing in the Gorge. What makes the Gorge a special place to sail? It is really one of the legendary venues of the world. But it’s not really in the classic model because the local sailing community created it from scratch. It’s a pretty unique situation; it still has that home-grown feel to it, sort of a low key aspect which is different from sailing in San Francisco or someplace like that. It’s all about having a good time and enjoying the beautiful place that it is. But at the same time, there is consistently a very high level of race management. So even though the vibe is pretty relaxed, that doesn’t mean we don’t have really great racing. The focus is on the sailing. And, of course, getting better at sailing in stronger winds! That’s one thing the Gorge is uniquely suited for. How does this compare to other heavy air venues? It’s a low risk way to get better at strong wind sailing. A lot of the windy places are either not windy all the time or so windy that they’re really intimidating. -

The 48Th 24 Hour Race Special

mastThe THE MAGAZINE FOR THE COMPETITIVE SAILOR THE 48TH 24 HOUR RACE SPONSORED BY SPECIAL THE CREWSAVER 24 HOUR DINGHY RACE WEST LANCASHIRE YACHT CLUB 13th & 14th September 2014 Ian Donaldson Commodore As Commodore of West Lancashire Yacht Club it is a great honour for me to welcome all competitors, sponsors, and many long standing friends and guests to our Club. We truly appreciate your continued support for the Crewsaver 24 Hour Race, an unrivalled event, now in its 48th year. HEN planning for the original race in 1967, although our the Race. We are also indebted to Sefton Metropolitan members were filled with great enthusiasm, I suspect that Borough Council for their support, with parking they never thought that the event would still be going arrangements and waste disposal. strong nearly 50 years later. In fact a number of teams Isaac Marsh & Robin Jones from Scammonden Water Sailing Whave competed in virtually every race since then. Club are aiming to complete the full 24 hours to raise money The race originally grew from a 12 hour race, the "British Universities for the Andrew Simpson Sailing Foundation. This charity will Championship", held on the Marine Lake in 1966 and was initially be familiar to everyone in the sailing community and we competed for by the two fleets of Enterprises and GP's. The basic hope you will support this challenge. idea, which has been retained, was for each team's boat to sail around I must also mention the enthusiasm of members of the Marine Lake for twenty four hours, with the one which sailed the Liverpool Yacht Club. -

0462309X 11 16 4 50 1 0112180E 5 5 50 1 1256657T 5 4 6 42 3 5 4

Championnat de Seine et Marne 2019 Choisy le Roi MELUN Gde Paroisse Montereau Vaires sur Marne Dammarie Les Praillons YCPF Seine Port St Fargeau Classement Dériveurs 10-mars 7-avr. 28-avr. 12-mai 26-mai 1-sept. 8-sept. 15-sept. 22-sept. championnat nbr bateaux participants nbr bateaux participants nbr bateaux participants nbr bateaux participants nbr bateaux participants nbr bateaux participants nbr bateaux participants nbr bateaux participants nbr bateaux participants participants 0 0 12 20 11 19 0 0 14 22 11 17 16 28 8 13 5 9 76 Place nbr licences coureurs / équipage club série pts série pts série pts série pts série pts série pts série pts série pts série pts pts REGATES 0462309X THOMAS JEROME C S MONTERELAIS SNIPE 12 SNIPE 11 SNIPE 11 SNIPE 16 4 50 1 16 0112180E DEPOUX PASCAL C.N DE VAIRES LASER STANDARD 13 LASER STANDARD 10 LASER STANDARD 14 LASER STANDARD 8 LASER STANDARD 5 5 50 1 14 1256657T MORTREUIL CLAIRE YCPF VAURIEN CLASSIQUE 5 VAURIEN CLASSIQUE 9 VAURIEN CLASSIQUE 9 VAURIEN CLASSIQUE 13 VAURIEN CLASSIQUE 2 VAURIEN CLASSIQUE 4 6 42 3 13 0609212W SOLAZZO ARNAUD YCPF VAURIEN CLASSIQUE 5 VAURIEN CLASSIQUE 9 VAURIEN CLASSIQUE 9 VAURIEN CLASSIQUE 13 VAURIEN CLASSIQUE 2 VAURIEN CLASSIQUE 4 6 42 3 13 1411683D THOMAS GABIN C S MONTERELAIS SNIPE 12 SNIPE 11 SNIPE 16 3 39 5 16 1377699D KLIMCZYK GRZEGORZ C S MONTERELAIS SNIPE 10 SNIPE 11 SNIPE 15 3 36 6 15 1316221P THOMAS TITOUAN C S MONTERELAIS SNIPE 11 SNIPE 10 SNIPE 15 3 36 6 15 1124433K BAILLET ALEXIS C N PRAILLONS 505 10 505 6 505 10 505 7 4 33 8 10 1048330L LECLERE EMMANUEL AS -

470 Etimes Issue: Dec Ember 2009

470 Worlds Stats Men‘s 470 Top 10 10 nations/4 continents Women‘s 470 Top 10 9 nations/4 continents :: Page 8 Joe Glanfield: —I love the 470. It‘s a boat that incorporates every aspect of dinghy racing.“ :: Page 4 Photo: Sander van der Borgh 470 ETIMES ISSUE: DEC EMBER 2009 Photo: Getty Images WWW.470.ORG 470 ETIMES The eTimes is the official newsletter of the International 470 Class Association All rights reserved: 470 Internationale© DISTR IBUTION Beijing 2008 Women‘s 470 bronze medallist Isabel Swan and World‘s best - National Class Associations - Sailing Federations soccer player Pele support Rio de Janeiro‘s bid for the 2016 Olympics. - 470 sailors & spectators WHAT THE BEIJING M EDALLISTS DID NEXT? - (Sailing) Sport Media ANDY RICE CAUGHT UP WITH THE 470 OLYMPIC M EDALLISTS FROM BEIJING - ISAF :: P AGE 3-4 The 470 eTimes is distributed 470 ET IMES INDEX through the International 470 WORDS FROM THE PRESIDENT Class emailing list, and through 470 CLASS SAILORS‘ SUPPORT PRORAMMES the official 470 Class web site: ñ WHAT HAPPENNED AFTER BEIJING ? MORE PROGRAMMES, www.470.org ñ SAILOR’S SU PPORT PROGRAMME S ñ CHAMPIONSHIP REVIEW S INCREASING GLOBAL EXPA NSION. P HOTOGRAPHY With many thanks to: ñ MASTERS AND LEGENDS The International 470 Class offers more Support programmes, more knowledge transfer and more support to sailors‘ Olympic campaigns. - Getty Images ñ ISAF WORLD CU P - Sander van der Borgh - Thom Touw ñ ATHLETES’ COMMISSION ñ CALENDAR :: P AGE 5 -6 EDITORIAL: ñ OLYMPIC Q U ALIFICATION Contributions of Luissa Smith ñ 470 ATHLETES Andy Rice Rick van Wijngaarden WOMEN‘S SA ILING - WORLDS‘ FLEET T OP 20 Edward Ramsden Five 420 Ladies‘ World Championship medallists, two 470 ATHLETES Hubert Kirrmann out of three girls who have ever won the overall Top players in the International 470 Nicholas Guichet Class. -

Bootsempfehlung Für Das Heimatrevier Ellerazhofer Weiher Heraus

Der Marine Verein Wangen 1926 e.V. gibt nachstehende Bootsempfehlung für das Heimatrevier Ellerazhofer Weiher heraus. Grundlage der Liste ist die offizielle Yardstick-Liste des Jahres 2013. Ziel ist das gemeinsame, vergleichbare Segeln in den Klassen 1-Hand, 2-Hand und Optimist. Hiermit werden uns Regattaläufe ermöglicht, bei denen ein Zieleinlauf im angestrebten Zeitfenster von max. 15 Minuten erfolgt. Die Zuschauer an Land können die Positionen auf dem Wasser erkennen. Bootstypen, die bereits erfolgreich bei Regatten auf unserem Revier eingesetzt wurden, sind farblich hervorgehoben. Diese haben Vorrang bei der Liegeplatzvergabe. A-Cat XL 73 Topcat F2 SC 93 Nacra Inter 20 74 Flying Dutchman/FD 94 Tornado, olympisch 74 Int. 14-Fuß-Dinghi bis 1995 94 Int. 18-Fuß-Dinghi 76 29er 95 A-Cat 76 505er 95 BIM 18 76 Laser 4000 95 Hobie-Cat 20 76 Z-Jolle (20 qm) 96 Nacra 6.0 76 Hobie-Cat 14 Turbo 96 Prindle 19 77 20qm Jollenkr. Renn. 97 Formel 20 78 H-Jolle alt Bau Nr.766-849 97 Nacra F 18 78 Javelin 97 Nacra Inter 18 78 I C Segel-Kanu 98 Tornado, alt 78 Laser 3000 98 Dart Hawk 79 V-Jolle 99 Formel 18 79 Hobie-Cat 14 99 Hobie-Cat 18 Tiger 79 Topcat F1 Classic 99 Prindle 18/2 79 Topcat F2 Classic 99 Dart 20 80 30qm Jollenkr. Renn. 100 Hobie-Cat 18 Formula 80 J ( 22 qm ) Rennjolle 100 49er - Neues Rigg 81 Supertiki 100 49er 82 15qm Jollenkr. Renn. 101 Hobie-Cat 18 82 Enterprise 102 Prindle 18 82 Jet 102 Spitfire 3 / Topcat K1 82 Windy 102 Nacra 5.2 83 470er 103 Min. -

Download the Digital Version of Our Latest WINDY

Contents 32 58 06 16 Wildest dream 22 Out of the shadows 06 Eating with the fishes A new single-malt whisky. Made of In case you missed it the first time A truly in-your-face seafood experience, seawater. On an island in the Arctic round – a new take on classic courtesy of one of the world’s leading Circle. What could go wrong? Scandinavian furniture design. architecture studios. 24 Stellar cuisine 39 Hide and chic 08 Big idea Heidi Bjerkan’s Stockholm restaurant Hand-crafted, traditional and tanned They don’t get bigger – a state-of-the- had a vintage 2019 – the Michelin star in the old way – beautiful leather art research ship that is also the world’s was only half the story. accessories from England. largest megayacht. 32 Infinite variety 44 Jensen's lasting legacy 60 Staying current There is nowhere on earth quite like it Of all the great names associated with At last, a clean conscience for you and – is Argentina the ultimate adventure Scandinavian jewellery design, one rises a bright green future for your beloved travel destination? above all others. classic automobile. 50 This crazy thing 58 Boats that sink Things are changing among Swiss Craftsman, artist, sculptor, visionary alpine resorts, thanks to an injection – Bertil Vallien is a glassmaker who MONTIS NORDIC AS· T: +47 33 12 50 00 MONTIS NORDIC AS· T: of Middle Eastern cash. transcends description. 14 Scream factory An imposing new home for the work of expressionist Edvard Munch, Oslo’s most famous son. 26 Out of the box News from the 67 It’s 50 years since his first studio date, world of Windy but he did start young – a profile of the guitarist Earl Klugh. -

Governor's Cup in April!

AUSTIN YACHT CLUB TELLTALE April 2017 Governor’s Cup in April! Photo Bill Records IN THIS ISSUE SAVE THE DATE Board of Director Reports Apr 21, 28 Beer Can Races May 6-7 Women’s Sailing Clinic Notes from Your GM Apr 21-23 Sea Scout Sometimes Island Sail Days May 7, 14, 21 Smallboat Intro to Sailing Series Apr 22-23 ASA 101 Course May 7, 21 Summer Series Races New Members Apr 22-23 SEISA Coed Championship Regatta May 12, 19, 26 Beer Can Races Sailing Director Report Apr 22 Scott Young Start Clinic May 12-14 J22 Southwest Circuit Regatta Roadrunner News Apr 23,30 Smallboat Intro to Sailing Series May 13-14 ASA 101 Course ASA Instructor Training Apr 27 AYC Board Meeting May 20 Powerboat Safety Course Governor’s Cup Regatta Apr 29 Keelboat Learn to Sail Clinic May 21 Girl Scout Learn to Sail Optis Apr 30 Summer Series #1 May 25 AYC Board Meeting MoonBurn Regatta May 3, 10, 17, 24, 31 Sunfish/Laser Racing May 27-28 Spring High School Regatta Fleet Captain Updates May 5 MoonBurn Night Race #1 May 27-28 Turnback Canyon Regatta May 6 High School Intro Regatta Turn aB ck Canyon Regatta AYC 2017 ` Memorial Day weekend May 27-28, 2017 Memorial Day Weekend 5/27– 5/28 ` 2 days,Tw 20+o d milesays, 20on Lake+ mi lesTravis on up L aandke backTrav fromis up Austin and bYachtack Club to Lago Vista. ` Open ftoro allm sailboatAustin classes.Yacht C lub to Lago Vista. Overnight ` Awards,an t-shirts,chorag pre/poste, and camping.race parties LagoFestat AYC. -

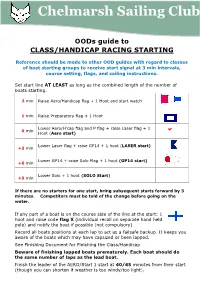

Class Handicap Starting

Chelmarsh Sailing Club OODs guide to CLASS/HANDICAP RACING STARTING Reference should be made to other OOD guides with regard to classes of boat starting groups to receive start signal at 3 min intervals, course setting, flags, and sailing instructions. Set start line AT LEAST as long as the combined length of the number of boats starting. 2 min Raise Aero/Handicap flag + 1 Hoot and start watch 1 min Raise Preparatory flag + 1 Hoot Lower Aero/H’cap flag and P flag + raise Laser flag + 1 0 min Hoot (Aero start) Lower Laser flag + raise GP14 + 1 hoot (LASER start) +3 min Lower GP14 + raise Solo Flag + 1 hoot (GP14 start) +6 min Lower Solo + 1 hoot (SOLO Start) +9 min If there are no starters for one start, bring subsequent starts forward by 3 minutes. Competitors must be told of the change before going on the water. If any part of a boat is on the course side of the line at the start: 1 hoot and raise code flag X (individual recall on separate hand held pole) and notify the boat if possible (not compulsory) Record all boats positions at each lap to act as a failsafe backup. It keeps you aware of the boats which may have capsized or been lapped. See Finishing Document for Finishing the Class/Handicap Beware of finishing lapped boats prematurely. Each boat should do the same number of laps as the lead boat. Finish the leader of the AERO/Start 1 start at 40/45 minutes from their start (though you can shorten if weather is too windy/too light).