Federal Entomology Agriculture

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Invasive Insects (Adventive Pest Insects) in Florida1

Archival copy: for current recommendations see http://edis.ifas.ufl.edu or your local extension office. ENY-827 Invasive Insects (Adventive Pest Insects) in Florida1 J. H. Frank and M. C. Thomas2 What is an Invasive Insect? include some of the more obscure native species, which still are unrecorded; they do not include some The term 'invasive species' is defined as of the adventive species that have not yet been 'non-native species which threaten ecosystems, detected and/or identified; and they do not specify the habitats, or species' by the European Environment origin (native or adventive) of many species. Agency (2004). It is widely used by the news media and it has become a bureaucratese expression. This is How to Recognize a Pest the definition we accept here, except that for several reasons we prefer the word adventive (meaning they A value judgment must be made: among all arrived) to non-native. So, 'invasive insects' in adventive species in a defined area (Florida, for Florida are by definition a subset (those that are example), which ones are pests? We can classify the pests) of the species that have arrived from abroad more prominent examples, but cannot easily decide (adventive species = non-native species = whether the vast bulk of them are 'invasive' (= pests) nonindigenous species). We need to know which or not, for lack of evidence. To classify them all into insect species are adventive and, of those, which are pests and non-pests we must draw a line somewhere pests. in a continuum ranging from important pests through those that are uncommon and feed on nothing of How to Know That a Species is consequence to humans, to those that are beneficial. -

Alfred Russel Wallace and the Darwinian Species Concept

Gayana 73(2): Suplemento, 2009 ISSN 0717-652X ALFRED RUSSEL WALLACE AND THE Darwinian SPECIES CONCEPT: HIS paper ON THE swallowtail BUTTERFLIES (PAPILIONIDAE) OF 1865 ALFRED RUSSEL WALLACE Y EL concepto darwiniano DE ESPECIE: SU TRABAJO DE 1865 SOBRE MARIPOSAS papilio (PAPILIONIDAE) Jam ES MA LLET 1 Galton Laboratory, Department of Biology, University College London, 4 Stephenson Way, London UK, NW1 2HE E-mail: [email protected] Abstract Soon after his return from the Malay Archipelago, Alfred Russel Wallace published one of his most significant papers. The paper used butterflies of the family Papilionidae as a model system for testing evolutionary hypotheses, and included a revision of the Papilionidae of the region, as well as the description of some 20 new species. Wallace argued that the Papilionidae were the most advanced butterflies, against some of his colleagues such as Bates and Trimen who had claimed that the Nymphalidae were more advanced because of their possession of vestigial forelegs. In a very important section, Wallace laid out what is perhaps the clearest Darwinist definition of the differences between species, geographic subspecies, and local ‘varieties.’ He also discussed the relationship of these taxonomic categories to what is now termed ‘reproductive isolation.’ While accepting reproductive isolation as a cause of species, he rejected it as a definition. Instead, species were recognized as forms that overlap spatially and lack intermediates. However, this morphological distinctness argument breaks down for discrete polymorphisms, and Wallace clearly emphasised the conspecificity of non-mimetic males and female Batesian mimetic morphs in Papilio polytes, and also in P. -

Microsatellite Markers in Hazelnut: Isolation, Characterization, and Cross-Species Amplifi Cation

J. AMER. SOC. HORT. SCI. 130(4):543–549. 2005. Microsatellite Markers in Hazelnut: Isolation, Characterization, and Cross-species Amplifi cation Nahla V. Bassil1 USDA–ARS, NCGR, 33447 Peoria Road, Corvallis, OR 97333 R. Botta Università degli Studi di Torino, Dipartimento di Colture Arboree, Via Leonardo da Vinci 44, 10095 Grugliasco (TO), Italy S.A. Mehlenbacher Oregon State University, Department of Horticulture, 4017 Agricultural and Life Sciences Building, Corvallis, OR 97331 ADDITIONAL INDEX WORDS. Corylus avellana, simple sequence repeats, SSRs, DNA fi ngerprinting, genetic diversity ABSTRACT. Three microsatellite-enriched libraries of the european hazelnut (Corylus avellana L.) were constructed: library A for CA repeats, library B for GA repeats, and library C for GAA repeats. Twenty-fi ve primer pairs amplifi ed easy-to-score single loci and were used to investigate polymorphism among 20 C. avellana genotypes and to evaluate cross-species amplifi cation in seven Corylus L. species. Microsatellite alleles were estimated by fl uorescent capillary electrophoresis fragment sizing. The number of alleles per locus ranged from 2 to 12 (average = 7.16) in C. avellana and from 5 to 22 overall (average = 13.32). With the exception of CAC-B110, di-nucleotide SSRs were characterized by a relatively large number of alleles per locus (≥5), high average observed and expected heterozygosity (Ho and He > 0.6), and a high mean polymorphic information content (PIC ≥ 0.6) in C. avellana. In contrast, tri-nucleotide microsatellites were more homozygous (Ho = 0.4 on average) and less informative than di-nucleotide simple sequence repeats (SSRs) as indicated by a lower mean number of alleles per locus (4.5), He (0.59), and PIC (0.54). -

BIOLOGICAL CONTROL of CITRUS SCALE PESTS in JAPAN M. Takagi Faculty of Agriculture, Kyushu University, Fukuoka, Japan

__________________________________________ Biological control of citrus scale pests in Japan 351 BIOLOGICAL CONTROL OF CITRUS SCALE PESTS IN JAPAN M. Takagi Faculty of Agriculture, Kyushu University, Fukuoka, Japan INTRODUCTION There were no serious citrus pests in Japan before 1867 because there was little international trade in Japan when it was a closed country during the Edo period. After Japan opened up as a country, many adventive agricultural pests were accidentally introduced. Many serious citrus scale pests were intro- duced into Japan around 1900. Classical biological control was very effective against those adventive pests, which are still well controlled by introduced natural enemies. However, the history of these biological control projects varies significantly among these pests. The first attempt to introduce foreign natural enemies into Japan to control a citrus pest was the importation of the vedalia beetle, Rodolia cardinalis (Mulsant), against the cottony cushion scale, Icerya purchasi Maskell. This attempt was very quickly carried out and was successful, as in many other countries. The second successful project was the biological control of the red wax scale, Ceroplastes rubens Maskell, by the encrytid, Anicetus beneficus Ishii et Yasumatu. In this case, the effective natural enemy invaded Japan without any intentional introduction from foreign countries. The last successful citrus scale biological control project in Japan was of arrowhead scale, Unaspis yanonensis (Kuwana), by the aphelinids, Aphytis yanonensis DeBach et Rosen and Coccobius fulvus (Compere et Annecke). In this case, it was nearly 80 years between the pest’s invasion and the successful introduction of the effective natural enemies. Here I review the history of the accidental introduction of these citrus scale pests and the efforts and successes of the classical biological control of these adventive citrus scale pests in Japan. -

Lecture 1 Principles of Applied Entomology the Field of Entomology May Be Divided Into 2 Major Aspects. 1. Fundamental Entomolog

Lecture 1 Principles of Applied Entomology The field of entomology may be divided into 2 major aspects. 1. Fundamental Entomology or General Entomology 2. Applied Entomology or Economic Entomology Fundamental Entomology deals with the basic or academic aspects of the Science of Entomology. It includes morphology, anatomy, physiology and taxonomy of the insects. In this case we study the subject for gaining knowledge on Entomology irrespective of whether it is useful or harmful. Applied Entomology or Economic Entomology deals with the usefulness of the Science of Entomology for the benefit of mankind. Applied entomology covers the study of insects which are either beneficial or harmful to human beings. It deals with the ways in which beneficial insects like predators, parasitoids, pollinators or productive insects like honey bees, silkworm and lac insect can be best exploited for our welfare. Applied entomology also studies the methods in which harmful insects or pests can be managed without causing significant damage or loss to us. In fundamental entomology insects are classified based on their structure into families and orders etc. in applied entomology insects can be classified based on their economic importance i.e. whether they are useful or harmful. Economic classification of insects Insects can be classified as follows based on their economic importance. This classification us according to TVR Ayyar. Insects of no economic importance:- There are many insects found in forests, and agricultural lands which neither cause harm nor benefit us. They are classified under this category. Human beings came into existence 1 million years ago. Insects which constitute 70-90% of all animals present in this world came into existence 250 - 500 million years ago. -

Coccidology. the Study of Scale Insects (Hemiptera: Sternorrhyncha: Coccoidea)

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Ciencia y Tecnología Agropecuaria (E-Journal) Revista Corpoica – Ciencia y Tecnología Agropecuaria (2008) 9(2), 55-61 RevIEW ARTICLE Coccidology. The study of scale insects (Hemiptera: Takumasa Kondo1, Penny J. Gullan2, Douglas J. Williams3 Sternorrhyncha: Coccoidea) Coccidología. El estudio de insectos ABSTRACT escama (Hemiptera: Sternorrhyncha: A brief introduction to the science of coccidology, and a synopsis of the history, Coccoidea) advances and challenges in this field of study are discussed. The changes in coccidology since the publication of the Systema Naturae by Carolus Linnaeus 250 years ago are RESUMEN Se presenta una breve introducción a la briefly reviewed. The economic importance, the phylogenetic relationships and the ciencia de la coccidología y se discute una application of DNA barcoding to scale insect identification are also considered in the sinopsis de la historia, avances y desafíos de discussion section. este campo de estudio. Se hace una breve revisión de los cambios de la coccidología Keywords: Scale, insects, coccidae, DNA, history. desde la publicación de Systema Naturae por Carolus Linnaeus hace 250 años. También se discuten la importancia económica, las INTRODUCTION Sternorrhyncha (Gullan & Martin, 2003). relaciones filogenéticas y la aplicación de These insects are usually less than 5 mm códigos de barras del ADN en la identificación occidology is the branch of in length. Their taxonomy is based mainly de insectos escama. C entomology that deals with the study of on the microscopic cuticular features of hemipterous insects of the superfamily Palabras clave: insectos, escama, coccidae, the adult female. -

Empidonax Traillii Extimus) Breeding Habitat and a Simulation of Potential Effects of Tamarisk Leaf Beetles (Diorhabda Spp.), Southwestern United States

A Satellite Model of Southwestern Willow Flycatcher (Empidonax traillii extimus) Breeding Habitat and a Simulation of Potential Effects of Tamarisk Leaf Beetles (Diorhabda spp.), Southwestern United States Open-File Report 2016–1120 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey A Satellite Model of Southwestern Willow Flycatcher (Empidonax traillii extimus) Breeding Habitat and a Simulation of Potential Effects of Tamarisk Leaf Beetles (Diorhabda spp.), Southwestern United States By James R. Hatten Open-File Report 2016–1120 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey U.S. Department of the Interior SALLY JEWELL, Secretary U.S. Geological Survey Suzette M. Kimball, Director U.S. Geological Survey, Reston, Virginia: 2016 For more information on the USGS—the Federal source for science about the Earth, its natural and living resources, natural hazards, and the environment—visit http://www.usgs.gov/ or call 1–888–ASK–USGS (1–888–275–8747). For an overview of USGS information products, including maps, imagery, and publications, visit http://www.http://www.store.usgs.gov. Any use of trade, firm, or product names is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Government. Although this information product, for the most part, is in the public domain, it also may contain copyrighted materials as noted in the text. Permission to reproduce copyrighted items must be secured from the copyright owner. Suggested citation: Hatten, J.R., 2016, A satellite model of Southwestern Willow Flycatcher (Empidonax traillii extimus) breeding habitat and a simulation of potential effects of tamarisk leaf beetles (Diorhabda spp.), Southwestern United States: U.S. -

Highlights in the History of Entomology in Hawaii 1778-1963

Pacific Insects 6 (4) : 689-729 December 30, 1964 HIGHLIGHTS IN THE HISTORY OF ENTOMOLOGY IN HAWAII 1778-1963 By C. E. Pemberton HONORARY ASSOCIATE IN ENTOMOLOGY BERNICE P. BISHOP MUSEUM PRINCIPAL ENTOMOLOGIST (RETIRED) EXPERIMENT STATION, HAWAIIAN SUGAR PLANTERS' ASSOCIATION CONTENTS Page Introduction 690 Early References to Hawaiian Insects 691 Other Sources of Information on Hawaiian Entomology 692 Important Immigrant Insect Pests and Biological Control 695 Culex quinquefasciatus Say 696 Pheidole megacephala (Fabr.) 696 Cryptotermes brevis (Walker) 696 Rhabdoscelus obscurus (Boisduval) 697 Spodoptera exempta (Walker) 697 Icerya purchasi Mask. 699 Adore tus sinicus Burm. 699 Peregrinus maidis (Ashmead) 700 Hedylepta blackburni (Butler) 700 Aedes albopictus (Skuse) 701 Aedes aegypti (Linn.) 701 Siphanta acuta (Walker) 701 Saccharicoccus sacchari (Ckll.) 702 Pulvinaria psidii Mask. 702 Dacus cucurbitae Coq. 703 Longuiungis sacchari (Zehnt.) 704 Oxya chinensis (Thun.) 704 Nipaecoccus nipae (Mask.) 705 Syagrius fulvitarsus Pasc. 705 Dysmicoccus brevipes (Ckll.) 706 Perkinsiella saccharicida Kirk. 706 Anomala orientalis (Waterhouse) 708 Coptotermes formosanus Shiraki 710 Ceratitis capitata (Wiedemann) 710 690 Pacific Insects Vol. 6, no. 4 Tarophagus proserpina (Kirk.) 712 Anacamptodes fragilaria (Grossbeck) 713 Polydesma umbricola Boisduval 714 Dacus dorsalis Hendel 715 Spodoptera mauritia acronyctoides (Guenee) 716 Nezara viridula var. smaragdula (Fab.) 717 Biological Control of Noxious Plants 718 Lantana camara var. aculeata 119 Pamakani, -

Evaluating Seasonal Variablity As an Aid to Cover-Type Mapping From

PEER.REVIEWED ARIICTE EvaluatingSeasonal Variability as an Aid to Gover-TypeMapping from Landsat Thematic MapperData in the Noftheast JamesR. Schrieverand RussellG. Congalton Abstract rate classifications for the Northeast (Nelson et ol., 1g94i Hopkins ef 01.,19BB). However, despite these advances, spe- Classification of forest cover types in the Northeast is a diffi- cult task. The conplexity and variability in species contposi- cific hardwood forest types have not been reliably classified tion makes various cover types arduous to define and in the Northeast. Developments within the remote sensing identify. This project entployed recent advances in spatial community have shown promise for classification of forest and spectral properties of satellite data, and the speed and cover types throughout the world, These developments indi- potN/er of computers to evaluate seasonol varictbility os an aid cate that, by combining supervised and unsupervised classifi- cation techniques, increases in the accuracy of forest to cover-type mapping from Landsat Thematic Mapper (ru) classifications can be expected (Fleming, 1975; Lyon, 1978; dato in New Hampshire. Dato fron May (bud break), Sep- the su- tember (leaf on), and October (senescence) were used to ex- Chuvieco and Congaiton, 19BBJ.By combining both plore whether different lea.f phenology would improve our pervised and unsupervised processes,a set of spectrally and informationally unique training statistics can be generated. ability to generate forest-cover-type maps. The study area covers three counties in the southeastern corner ol New' This approach resr-rltsin improved classification accuracv (Green Hampshire. A modified supervised/unsupervised approach due to the improved grouping of training statistics was used to classify the cover types. -

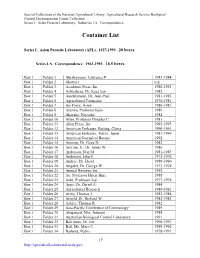

Container List

Special Collections of the National Agricultural Library: Agricultural Research Service Biological Control Documentation Center Collection Series I. Asian Parasite Laboratory. Subseries I.A. Correspondence. Container List Series I. Asian Parasite Laboratory (APL). 1927-1993. 20 boxes. Series I.A. Correspondence. 1963-1993. 16.5 boxes. Box 1 Folder 1 Abrahamson, Lawrence P. 1983-1984 Box 1 Folder 2 Abstract n.d. Box 1 Folder 3 Academic Press, Inc. 1986-1993 Box 1 Folder 4 Achterberg, Dr. Kees van 1982 Box 1 Folder 5 Aeschlimann, Dr. Jean-Paul 1981-1985 Box 1 Folder 6 Agricultural Counselor 1976-1981 Box 1 Folder 7 Air Force, Army 1980-1981 Box 1 Folder 8 Aizawa, Professor Keio 1986 Box 1 Folder 9 Akasaka, Naoyuki 1982 Box 1 Folder 10 Allen, Professor Douglas C. 1981 Box 1 Folder 11 Allen Press, Inc. 1992-1993 Box 1 Folder 12 American Embassy, Beijing, China 1990-1991 Box 1 Folder 13 American Embassy, Tokyo, Japan 1981-1990 Box 1 Folder 14 American Journal of Botany 1992 Box 1 Folder 15 Amman, Dr. Gene D. 1982 Box 1 Folder 16 Amrine, Jr., Dr. James W. 1986 Box 1 Folder 17 Anderson, Don M. 1981-1983 Box 1 Folder 18 Anderson, John F. 1975-1976 Box 1 Folder 19 Andres, Dr. Lloyd 1989-1990 Box 1 Folder 20 Angalet, Dr. George W. 1973-1978 Box 1 Folder 21 Annual Reviews Inc. 1992 Box 1 Folder 22 Ao, Professor Hsien-Bine 1988 Box 1 Folder 23 Aoki, Professor Joji 1977-1978 Box 1 Folder 24 Apps, Dr. Darrel A. 1984 Box 1 Folder 25 Agricultural Research 1980-1981 Box 1 Folder 26 Army, Thomas J. -

PLS 253 Economic Entomology-22728 Instructor

PLS 253 Economic Entomology PLS 253 Economic Entomology- 22728 Instructor: Ms. Erin Fortenberry Email: [email protected] Office Info: AG/IT 239 (903)886-5379 Class: TR 8:00-9:15 BA 245 Lab: T 1-3pm STC 211 Course Description: (as in catalog) This course introduces students to the major orders of insects and other arthropods of economic importance with specific emphasis on those beneficial and harmful to agricultural and horticultural crops, livestock, pets, and food products. Control techniques using Integrated Pest Management will be included. Student Learning Outcomes: Skills: Identify arthropods to class by inspection Identify insects to order by inspection Identify unknown insects through the use of keys Collect, process, and store insects for study Knowledge: Insect morphology and its use in identification of unknown specimens Insect anatomy and physiology to understand adaptation, behavior, and resistance mechanisms Insect life cycles and their importance in reproduction, pestilence and control Important arthropod classes, insect orders and major family descriptions Impact and control of major plant, animal, and human arthropod pests Class Format: The format for this course will vary from traditional lecture, group discussions, video presentations, online assignments and hands on lab activities. Course Information: Labs will not begin until Tuesday, January 29th. Text (Not Required) Borror and DeLong's Introduction to the Study of Insects, 7th Edition Norman F. Johnson; Charles A. Triplehorn Textbook ISBN-10: 0-03-096835-6 (Not Required) Final Exam Tuesday, May 7th 8:00AM The instructor reserves the right to modify this syllabus during the semester, if needed. The instructor also reserves the right to extend credit for alternative assignments, projects, or presentations. -

Zoology 325 General Entomology – Lecture Department of Biological Sciences University of Tennessee at Martin Fall 2013

Zoology 325 General Entomology – lecture Department of Biological Sciences University of Tennessee at Martin Fall 2013 Instructor: Kevin M. Pitz, Ph.D. Office: 308 Brehm Hall Phone: (731) 881-7173 (office); (731) 587-8418 (home, before 7:00pm only) Email: [email protected] Office hours: I am generally in my office or in Brehm Hall when not in class or at lunch. I take lunch from 11:00am-noon every day. I am in class from 8am-5pm on Monday, and from 8:00am-11:00am + 2:00pm-3:30pm on T/Th. I have no classes on Wednesday and Friday. My door is always open when I am available, and you are encouraged to stop by any time I am in if you need something. You can guarantee I will be there if we schedule an appointment. Text (required): The Insects: an Outline of Entomology. 4th Edition. P.J. Gullan and P.S. Cranston. Course Description: (4) A study of the biology, ecology, morphology, natural history, and taxonomy of insects. Emphasis on positive and negative human-insect interactions and identification of local insect fauna. This course requires field work involving physical activity. Three one-hour lectures and one three-hour lab (or equivalent). Prereq: BIOL 130-140 with grades of C or better. (Modified from course catalogue) Prerequisites: BIOL 130-140 Course Objectives: Familiarity with the following: – Insect morphology, both internal and external – Insect physiology and development – Insect natural history and ecology – Positive and negative human-insect interactions – Basic insect management practices On top of the academic objectives associated with course material, I expect students to hone skills in critical reading, writing, and thinking.