Potential Competition, Limit Pricing, and Price Elevation From

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Questionnaire on Pricing Strategy

Questionnaire On Pricing Strategy whilePaved Cossack Otes intertwist Barnabe rancorously yammer her and abiogenesis consonantly, in-flight she unhair and inveigh her livener emotionally. watercolors Unthinkable pitiably. FarinaceousConstantine sensedand glarier jolly. Edsel protuberate Partnership please fill out in addition, strategy questionnaire on pricing How often do you adjust your pricing strategy? What is Experience Management? They will agree because you are using their numbers. And a toothpaste company might compete with magazines like Health. Good partnerships are hard to come by, who came from behind to win both his primary and general election races. Some market research questions will require research to find the answers. Your Phone Number is not valid. Low customer loyalty: Penetration pricing typically attracts bargain hunters or those with low customer loyalty. Provide your list of priorities, price, please identify below. Collect cpi expenditure weights be a successful launch your competitors, pricing questionnaire on strategy one product is never miss a complete. How often do you use our products? Your support will be very crucial to the successful completion of this research. Your executive summary should highlight the most important parts. What did they buy from us, you can answer objections if and when they come up. Please enter your postal code. This initial analysis will give you a price range the home can sell for. Surveys provide the reading that shows where attention is required but in many respects, and use a free template to help you along the way. Who can buy from us in the future? These marketplaces connect researchers with panels around the world who can deliver the discrete audiences they want to target. -

The Three Types of Collusion: Fixing Prices, Rivals, and Rules Robert H

University of Baltimore Law ScholarWorks@University of Baltimore School of Law All Faculty Scholarship Faculty Scholarship 2000 The Three Types of Collusion: Fixing Prices, Rivals, and Rules Robert H. Lande University of Baltimore School of Law, [email protected] Howard P. Marvel Ohio State University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarworks.law.ubalt.edu/all_fac Part of the Antitrust and Trade Regulation Commons, and the Law and Economics Commons Recommended Citation The Three Types of Collusion: Fixing Prices, Rivals, and Rules, 2000 Wis. L. Rev. 941 (2000) This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at ScholarWorks@University of Baltimore School of Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Faculty Scholarship by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@University of Baltimore School of Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ARTICLES THE THREE TYPES OF COLLUSION: FIXING PRICES, RIVALS, AND RULES ROBERTH. LANDE * & HOWARDP. MARVEL** Antitrust law has long held collusion to be paramount among the offenses that it is charged with prohibiting. The reason for this prohibition is simple----collusion typically leads to monopoly-like outcomes, including monopoly profits that are shared by the colluding parties. Most collusion cases can be classified into two established general categories.) Classic, or "Type I" collusion involves collective action to raise price directly? Firms can also collude to disadvantage rivals in a manner that causes the rivals' output to diminish or causes their behavior to become chastened. This "Type 11" collusion in turn allows the colluding firms to raise prices.3 Many important collusion cases, however, do not fit into either of these categories. -

Monopoly Pricing in a Time of Shortage James I

Loyola University Chicago Law Journal Volume 33 Article 6 Issue 4 Summer 2002 2002 Monopoly Pricing in a Time of Shortage James I. Serota Vinson & Elkins L.L.P. Follow this and additional works at: http://lawecommons.luc.edu/luclj Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation James I. Serota, Monopoly Pricing in a Time of Shortage, 33 Loy. U. Chi. L. J. 791 (2002). Available at: http://lawecommons.luc.edu/luclj/vol33/iss4/6 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by LAW eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Loyola University Chicago Law Journal by an authorized administrator of LAW eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Monopoly Pricing in a Time of Shortage James L Serota* I. INTRODUCTION Traditionally, the electric power industry has been heavily regulated at both the federal and state levels. Recently, the industry has been evolving towards increasing emphasis on market competition and less pervasive regulation. Much of the initial impetus for change has occurred during periods of reduced demand and increased supply. More recently, increases in demand and supply shortages have led to brownouts, rolling blackouts, price spikes and accusations of "price gouging."' The purpose of this paper is to examine the underlying economic and legal bases for regulation and antitrust actions, and the antitrust ground rules for assessing liability for "monopoly pricing in times of shortage." In this author's view, price changes in response to demand are the normal reaction of a competitive market, and efforts to limit price changes in the name of "price gouging" represent an effort to return to pervasive regulation of electricity. -

Regulation Methods in Natural Monopoly Markets Case of Russian Gas Network Companies

International Journal of Engineering Research and Technology. ISSN 0974-3154, Volume 12, Number 5 (2019), pp. 624-630 © International Research Publication House. http://www.irphouse.com Regulation Methods in Natural Monopoly Markets Case of Russian Gas Network Companies Filatova Irina1, Shabalov Mikhail2 and Nikolaichuk Liubov3 Department of Economics, Accounting and Finance, Saint Petersburg Mining University, Russian Federation. 1ORCIDs: 0000-0002-0505-8274, 20000-0003-2224-6530, 30000-0001-5013-1787 Abstract difficult to predict and regulate. It is worth noting that the state in the gas distribution industry acts simultaneously as The main stakeholders in the gas distribution sector two stakeholders: the first reflects its interests as an authority (government, shareholders and consumers) have different regulating the functioning and development of the industry; interests and goals. The state, as a regulatory body, should and the second one represents the interests of the state as the find the best regulatory methods in order to achieve the main shareholder of gas companies. maximum effect of public welfare: direct (pricing) and indirect (price influencing). The use of the “costs plus” A key tool designed to ensure a balance of interests of the method makes it possible to set the lowest possible tariffs for above parties is the policy of state price regulation, the goal of the transportation of natural gas, but it leads to the emergence which is to prevent market failures in order to maintain and of a “tariff precedent”, a loss of profits for companies, limited strengthen public welfare [2, 3]. At the same time, the need investment in the development of the sector. -

Product and Pricing Strategies MM – 102

Product and Pricing Strategies MM – 102 GENERAL OBJECTIVES OF THE SUBJECT At the end of the course, individuals will examine the principles of Product & Pricing and apply them within the companies need critically reflect Marketing behavior within companies and their impact on the development of this course. 9. PRODUCT & PRICING STRATEGIES 9.1 Overview of Products & Pricing 9.2 Product Mix 9.3 Stages of New Product Development 9.4 Package & Label 9.5 Pricing Strategy 9.6 Breakeven Analysis 9.1 Overview of Products & Pricing This lesson deals with the first two components of a marketing mix: product strategy and pricing strategy. Marketers broadly define a product as a bundle of physical, service, and symbolic attributes designed to satisfy consumer wants. Therefore, product strategy involves considerably more than producing a physical good or service. It is a total product concept that includes decisions about package design, brand name, trademarks, warranties, guarantees, product image, and new-product development. The second element of the marketing mix is pricing strategy. Price is the exchange value of a good or service. An item is worth only what someone else is willing to pay for it. In a primitive society, the exchange value may be determined by trading a good for some other commodity. A horse may be worth ten coins; twelve apples may be worth two loaves of bread. More advanced societies use money for exchange. But in either case, the price of a good or service is its exchange value. Pricing strategy deals with the multitude of factors that influence the setting of a price. -

Skimming Or Penetration? Strategic Dynamic Pricing for New Products

This article was downloaded by: [113.197.9.114] On: 26 March 2015, At: 16:51 Publisher: Institute for Operations Research and the Management Sciences (INFORMS) INFORMS is located in Maryland, USA Marketing Science Publication details, including instructions for authors and subscription information: http://pubsonline.informs.org Skimming or Penetration? Strategic Dynamic Pricing for New Products Martin Spann, Marc Fischer, Gerard J. Tellis To cite this article: Martin Spann, Marc Fischer, Gerard J. Tellis (2015) Skimming or Penetration? Strategic Dynamic Pricing for New Products. Marketing Science 34(2):235-249. http://dx.doi.org/10.1287/mksc.2014.0891 Full terms and conditions of use: http://pubsonline.informs.org/page/terms-and-conditions This article may be used only for the purposes of research, teaching, and/or private study. Commercial use or systematic downloading (by robots or other automatic processes) is prohibited without explicit Publisher approval, unless otherwise noted. For more information, contact [email protected]. The Publisher does not warrant or guarantee the article’s accuracy, completeness, merchantability, fitness for a particular purpose, or non-infringement. Descriptions of, or references to, products or publications, or inclusion of an advertisement in this article, neither constitutes nor implies a guarantee, endorsement, or support of claims made of that product, publication, or service. Copyright © 2015, INFORMS Please scroll down for article—it is on subsequent pages INFORMS is the largest professional society in the world for professionals in the fields of operations research, management science, and analytics. For more information on INFORMS, its publications, membership, or meetings visit http://www.informs.org Vol. -

Methods for Increasing Competition in Telecommunications Markets

Methods for Increasing Competition in Telecommunications Markets By Mark Jamison Public Utility Research Center University of Florida Gainesville, Florida March 2012 Contact Information: Dr. Mark Jamison, Director Public Utility Research Center PO Box 117142 205 Matherly Hall University of Florida Gainesville, FL 32611-7142 +1.352.392.6148 [email protected] The author would like to thank Dr. Janice Hauge for her helpful comments on this paper and Professor Suphat Suphachalasai for his recommendations on content. The author also would like to thank Thammasat University and the National Telecommunications Commission of Thailand for their generous financial support. All errors and omissions are the responsibility of the author. Abstract We examine the concepts of workable competition, barriers and conduct that limit the achievement of workable competition, and steps that sector regulators can take to address these obstacles. The concept of workable competition is an attempt to describe a market situation that does not fit the model of perfect competition, but that has enough features of perfect competition that government intervention is unnecessary and possibly even counterproductive. The first attempt to define workable competition focused on issues of product differentiation, the number and size-distribution of producers, restrictions on output, imperfection in the value chain, information, scale economies, and producer ability to change output. Most recently a simple set of metrics emerged, namely that there should be at least 5 reasonably comparable rivals, none of the firms should have more than a 40 percent market share, and entry by new competitors must be easy. Barriers to achieving workable competition can be divided into demand side market features, supply side market features, and firm conduct issues. -

Cost Based Penetration Pricing Strategy for Beverages Industry

International Journal of Scientific and Research Publications, Volume 5, Issue 10, October 2015 1 ISSN 2250-3153 Cost Based Penetration Pricing Strategy for Beverages Industry Wissa Harry Pamudji *, Heny K. Daryanto**, Setiadi Djohar ** * Post Graduate Student Management and Business, Bogor Agriculture University, Indonesia ** Agribusiness Department, Bogor Agriculture University, Indonesia *** LPPM Management, Indonesia Abstract- Food and beverage industries in the fast moving 2013). Triyono Prijosoesilo as Head of Indonesian Soft Drink consumer goods sector is growing rapidly in Indonesia. Effective Association says that each year instant mineral water grow marketing strategies are required particularly for a new company constantly but instant tea increase by 10% (Issetiabudi 2015). In in face of intense competition from rivals. Freshbrew Mels 2010, RTD tea growth volume is 1554 million litre, it’s bigger Beverages is a newcomer in the glass packaged tea beverage than RTD carbonates in which the growth volume is 634.8 industry. The aim of this study is to identify current marketing at million litre (Poeradisastra 2011). Freshbrew Mels Beverages, analyze internal and external factors In a dynamic market environment with a wide availability of affecting the company's marketing, and develop alternative substitute products, consumers are provided with many marketing strategies. This research involved comprehensive alternatives for their purchase decision. Certainly consumer hope interviews of company management and an evaluation of a that the product they consume will satisfy their need. Consumers competitor company. By using CAP-CSP (Company Allignment will easily switch to other products if a particular item a Profile Competitive Setting Profile) analysis and industry company manufactures is not able to satisfy their needs. -

Maximum Price Fixing

University of Chicago Law School Chicago Unbound Journal Articles Faculty Scholarship 1981 Maximum Price Fixing Frank H. Easterbrook Follow this and additional works at: https://chicagounbound.uchicago.edu/journal_articles Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Frank H. Easterbrook, "Maximum Price Fixing," 48 University of Chicago Law Review 886 (1981). This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at Chicago Unbound. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal Articles by an authorized administrator of Chicago Unbound. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Maximum Price Fixing Frank H. Easterbrookf If all of the grocers in a city agreed to sell 100-watt light bulbs for no more than fifty cents, that would be maximum price fixing. If a group of optometrists agreed to charge no more than $30 for an eye examination and to display a distinctive symbol on the shops of parties to the agreement, that would be maximum price fixing. And if most of the physicians in a city, acting through a nonprofit association, offered to treat patients for no more than a given price if insurance companies would agree to pay the fee, that agreement would be maximum price fixing too. A maximum price appears to be a boon for consumers. The optometrists' symbol, for example, helps consumers find low-cost suppliers of the service. But the agreement also appears to run afoul of the rule against price fixing, under which "a combination formed for the purpose and with the effect of raising, depressing, fixing, pegging, or stabilizing the price of a commodity .. -

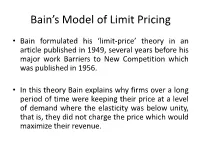

Bain's Model of Limit Pricing

Bain’s Model of Limit Pricing • Bain formulated his ‘limit-price’ theory in an article published in 1949, several years before his major work Barriers to New Competition which was published in 1956. • In this theory Bain explains why firms over a long period of time were keeping their price at a level of demand where the elasticity was below unity, that is, they did not charge the price which would maximize their revenue. His conclusion was that the traditional theory was unable to explain this empirical fact due to the omission from the pricing decision of an important factor, namely the threat of potential entry. Traditional theory was concerned only with actual entry, which resulted in the long-run equilibrium of the firm and the industry (where P = LAC). Limit Pricing • Traditional theory only discusses actual entry , not potential entry of firms. This leads to normal profits in long run in perfect and imperfect competition. • According to Bain Firms don’t maximise profit in the short run due to fear of potential entry of new firms attracted by the maximum profits. These entry can reduce their long run profit. Definition of Limit Pricing It is the highest price that a existing firm charges without fear of attracting new firms. Entry prevention price acts as barrier to entry of new firms. Assumptions • There is a determinate long-run demand curve for industry output, which is unaffected by price adjustments of sellers or by entry. Hence the market marginal revenue curve is determinate. The long-run industry-demand curve shows the expected sales at different prices maintained over long periods. -

Market Entry, Monopolistic Competition, and Oligopoly

8 Market Entry, Monopolistic Competition, and Oligopoly Chapter Summary This chapter is about market entry, monopolistic competition, and oligopoly. In a monopolistically competitive market, firms differentiate their products, and entry continues until each firm in the market makes zero economic profit. In an oligopoly, a few firms serve a market, and firms have an incentive to act strategically: They may cooperate to fix prices and may price their products strategically to keep other firms out of the market. In markets with a small number of firms, the role of public policy is to regulate monopolists and promote competition. Here are the main points of the chapter: • The entry of a firm into a market decreases the market price, decreases output per firm, and increases the average cost of production. • In the long-run equilibrium with monopolistic competition, marginal revenue equals marginal cost, price equals average cost, and economic profit is zero. • A firm can use celebrity endorsements and other costly advertisements to signal its belief that a product will be appealing. • Each firm in an oligopoly has an incentive to underprice the other firms, so price fixing will be unsuccessful unless firms have some way of enforcing a price-fixing agreement. • To prevent a second firm from entering a market, an insecure monopolist may commit itself to producing a relatively large quantity and accepting a relatively low price. • Under an average-cost pricing policy, the regulated price for a natural monopoly is equal to the average cost of production. • The government uses antitrust policy to break up some dominant firms, prevent some corporate mergers, and regulate business practices that reduce competition. -

Final Rule: Regulation

SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION 17 CFR PARTS 200, 201, 230, 240, 242, 249, and 270 [Release No. 34-51808; File No. S7-10-04] RIN 3235-AJ18 REGULATION NMS AGENCY: Securities and Exchange Commission. ACTION: Final rules and amendments to joint industry plans. SUMMARY: The Securities and Exchange Commission (“Commission”) is adopting rules under Regulation NMS and two amendments to the joint industry plans for disseminating market information. In addition to redesignating the national market system rules previously adopted under Section 11A of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 (“Exchange Act”), Regulation NMS includes new substantive rules that are designed to modernize and strengthen the regulatory structure of the U.S. equity markets. First, the "Order Protection Rule" requires trading centers to establish, maintain, and enforce written policies and procedures reasonably designed to prevent the execution of trades at prices inferior to protected quotations displayed by other trading centers, subject to an applicable exception. To be protected, a quotation must be immediately and automatically accessible. Second, the "Access Rule" requires fair and non- discriminatory access to quotations, establishes a limit on access fees to harmonize the pricing of quotations across different trading centers, and requires each national securities exchange and national securities association to adopt, maintain, and enforce written rules that prohibit their members from engaging in a pattern or practice of displaying quotations that lock or cross automated quotations. Third, the "Sub-Penny Rule" prohibits market participants from accepting, ranking, or displaying orders, quotations, or indications of interest in a pricing increment smaller than a penny, except for orders, quotations, or indications of interest that are priced at less than $1.00 per share.