Engineering Composite Materials

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Polymer Processing and Manufacturing Engineer Nushores

Polymer Processing and Manufacturing Engineer NuShores’ mission is to improve the quality of life for people globally while competing successfully by applying its licensed and internally developed advanced materials portfolio to the Biomaterials industry. NuShores has exclusive global license to patented bone and tissue regeneration technologies developed at University of Arkansas – Little Rock from over $12M in research. We are seeking a Polymer Processing and Manufacturing Engineer to Join our growing team to launch NuCress™ scaffold product family, our award-winning bone void filler line of medical device products. If working with a smart and creative team that designs and builds products that improve quality of life interests you, then consider a career with us. Job Type. Full-time professional employee. Reports To. The Polymer Process and Manufacturing Engineer will report to Chief Technical Officer, Chief Scientist or Product Manager. Salary. Competitive, with benefits. Job Overview. The Polymer Processing and Manufacturing Engineer will be the technical lead for new and existing processes that involve the integration of polymeric biomaterials to biological systems and products such as artificial bone and tissue medical devices. This role is responsible for concept development, equipment design and installation, vendor management, and process development and optimization for small to large-scale manufacturing readiness. A key focus for the Polymer Processing and Manufacturing Engineer is to lead process engineering to create and maintain a manufacturing line/facility. Additionally he/she will provide technical subject matter expertise in polymer structure-property relationships, catalyst, polymerization and to develop and maintain know-how and intellectual property within their relevant area of expertise to support regulatory and business objectives and sustain future growth. -

Investigating the Durability of Structures by Dana Saba Bachelor of Engineering, Mcgill University, Montréal, 2011

Investigating the Durability of Structures by Dana Saba Bachelor of Engineering, McGill University, Montréal, 2011 Submitted to the Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Engineering in Civil and Environmental Engineering at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology June 2013 © 2013 Massachusetts Institute of Technology. All rights reserved. Signature of Author: Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering May 10th, 2013 Certified by: Jerome J. Connor Professor of Civil and Environmental Engineering Thesis Supervisor Certified by: Rory Clune Massachusetts Institute of Technology Thesis Reader Accepted by: Heidi Nepf Chair, Departmental Committee for Graduate Students 2 Investigating the Durability of Structures by Dana Saba Submitted to the Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering in May 10, 2013, in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Engineering in Civil and Environmental Engineering Abstract The durability of structures is one of primary concerns in the engineering industry. Poor durability in design may result in a structure losing its performance to the extent where structural integrity is no longer satisfied and human lives are at stake. Moreover, the associated costs of maintenance and repair due to inadequate design considerations are high. Thus, designing for durable structures not only helps sustain our infrastructure, it also reduces future costs. This thesis identifies the key factors that define and impact durability, with particular attention paid to the effect of material choice on overall durability. This follows a study of the different deteriorating mechanisms that wood, steel and reinforced concrete undergo over time, and the different enhancement techniques used to reduce the adverse effects of these mechanisms. -

Material Quantities in Building Structures and Their Environmental Impact

Material quantities in building structures and their environmental impact by Catherine De Wolf B.Sc., M.Sc. in Civil Architectural Engineering Vrije Universiteit Brussel and Université Libre de Bruxelles, 2012 Submitted to the Department of Architecture in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science in Building Technology at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology June 2014 © 2014 Massachusetts Institute of Technology. All rights reserved. Signature of Author: Department of Architecture May 9, 2014 Certified by: John A. Ochsendorf Professor of Architecture and Civil and Environmental Engineering Thesis Supervisor Accepted by: Takehiko Nagakura Associate Professor of Design and Computation Chair of the Department Committee on Graduate Students John E. Fernández Professor of Architecture, Building Technology, and Engineering Systems Head, Building Technology Program Co-director, International Design Center, MIT Thesis Reader Frances Yang Structures and Sustainability Specialist at Arup Thesis Reader “It is […] important to remember that unlike operational carbon emissions the embodied carbon cannot be reversed” Craig Jones, Circular Ecology Material quantities in building structures and their environmental impact by Catherine De Wolf Submitted to the Department of Architecture in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science in Building Technology on May 9, 2014. Thesis Supervisor: John Ochsendorf Title Supervisor: Professor of Architecture and Civil and Environmental Engineering -

Applications of Aluminium Alloys in Civil Engineering

T. Dokšanović i dr. Primjene aluminijskih legura u građevinarstvu ISSN 1330-3651 (Print), ISSN 1848-6339 (Online) https://doi.org/10.17559/TV-20151213105944 APPLICATIONS OF ALUMINIUM ALLOYS IN CIVIL ENGINEERING Tihomir Dokšanović, Ivica Džeba, Damir Markulak Subject review Although aluminium is a long known structural material, its use is not in accordance with the benefits achieved by its implementation. There are several reasons for such an adverse state. Those that stand out are the late development of a regulative framework for the design of structures, and still the need for improvement, lack of knowledge on application examples and not stressed enough potential areas of use. However, positive trends are present and aluminium alloys are competitive, especially if their positive properties can be utilized and negative properties diminished through purpose oriented design approach. Given examples present good application utilization of aluminium alloys characteristics, and shown new application research can provide directions for further expansion of competitiveness. Structural uses are grouped in suitable areas of application and put into local and global context. Keywords: bridge; façade; refurbishment; roof system; seismic Primjene aluminijskih legura u građevinarstvu Pregledni članak Iako je aluminij već dugo prisutan konstrukcijski materijal, uporaba mu nije u skladu s dobrobitima koji se ostvaruju njegovom primjenom. Nekoliko je uzročnika takvog stanja. Ističu se relativno kasni razvoj normativnog okvira za dimenzioniranje konstrukcija, i još uvijek potreba za poboljšanjem, nedovoljna raširenost saznanja o primjenama te nedostatno naglašena potencijalna područja primjene. Međutim, pozitivni trendovi su prisutni, a legure aluminija su konkurentne, posebno ako se njegova pozitivna svojstva mogu iskoristiti, a negativna umanjiti kroz proračunski pristup orijentiran prema namjeni. -

Designing for Durability CONTINUING EDUCATION Strategies for Achieving Maximum Durability with Wood-Frame Construction Sponsored by Rethink Wood

EDUCATIONAL-ADVERTISEMENT Designing for Durability EDUCATION CONTINUING Strategies for achieving maximum durability with wood-frame construction Sponsored by reThink Wood rchitects specify wood for many Examples of wood buildings that have (glulam), cross laminated timber (CLT), and reasons, including cost, ease and stood for centuries exist all over the world, nail-laminated timber, along with a variety A efficiency of construction, design including the Horyu-ji temple in Ikaruga, of structural composite lumber products, are versatility, and sustainability—as well as Japan, built in the eighth century, stave enabling increased dimensional stability and its beauty and the innate appeal of nature churches in Norway, including one in Urnes strength, and greater long-span capabilities. and natural materials. Innovative new built in 1150, and many more. Today, wood These innovations are leading to taller, technologies and building systems are also is being used in a wider range of buildings highly innovative wood buildings. Examples leading to the increased use of wood as a than would have been possible even 20 years include (among others) a 10-story CLT structural material, not only in houses, ago. Next-generation lumber and mass timber apartment building in Australia, a 14-story schools, and other traditional applications, products, such as glue-laminated timber timber-frame apartment in Norway, but in larger, taller, and more visionary wood buildings. But even as the use of wood is expanding, one significant characteristic of wood buildings is often underestimated: their durability. Misperceptions still exist that buildings made of materials such as concrete or steel last longer than buildings made of wood. -

Structural Composite Materials Tailored for Damping

L Journal of Alloys and Compounds 355 (2003) 216–223 www.elsevier.com/locate/jallcom S tructural composite materials tailored for damping D.D.L. Chung* Composite Materials Research Laboratory, University at Buffalo, State University of New York, Buffalo, NY 14260-4400, USA Abstract This paper reviews the tailoring of structural composite materials for damping. By the use of the interfaces and viscoelasticity provided by appropriate components in a composite material, the damping capacity can be increased with negligible decrease, if any, of the stiffness. In the case of cement–matrix composites, the use of silica fume as an admixture results in increases in both the damping capacity and the storage modulus. In the case of continuous fiber polymer–matrix lightweight composites, the use of submicron-diameter discontinuous carbon filaments as an interlaminar additive is more effective than the use of an interlaminar viscoelastic layer in enhancing the loss modulus when the temperature exceeds 50 8C. Surface treatment of the composite components is important. In the case of steel reinforced concrete, the steel reinforcing bar (rebar) contributes much to the damping, but appropriate surface treatment of the rebar further enhances the damping. 2003 Elsevier Science B.V. All rights reserved. Keywords: Disordered systems; Polymers; Elastomers and plastics; Surfaces and interfaces; Elasticity; Anharmonicity 1 . Introduction [2–4] is the goal of the structural material tailoring described in this review paper. The development of materials for vibration and acoustic Vibrations are undesirable for structures, due to the need damping has been focused on metals and polymers [1]. for structural stability, position control, durability (par- Most of these materials are functional materials rather than ticularly durability against fatigue), performance, and noise practical structural materials due to their high cost, low reduction. -

Research Progress on Conducting Polymer-Based Biomedical Applications

applied sciences Review Research Progress on Conducting Polymer-Based Biomedical Applications Yohan Park 1, Jaehan Jung 2,* and Mincheol Chang 3,4,5,* 1 School of Materials Science and Engineering, Georgia Institute of Technology, Atlanta, GA 30332, USA; [email protected] 2 Department of Materials Science and Engineering, Hongik University, Sejong 30016, Korea 3 Department of Polymer Engineering, Graduate School, Chonnam National University, Gwangju 61186, Korea 4 School of Polymer Science and Engineering, Chonnam National University, Gwangju 61186, Korea 5 Alan G. MacDiarmid Energy Research Institute, Chonnam National University, Gwangju 61186, Korea * Correspondence: [email protected] (J.J.); [email protected] (M.C.); Tel.: +82-62-530-1771 (M.C.) Received: 23 February 2019; Accepted: 10 March 2019; Published: 14 March 2019 Abstract: Conducting polymers (CPs) have attracted significant attention in a variety of research fields, particularly in biomedical engineering, because of the ease in controlling their morphology, their high chemical and environmental stability, and their biocompatibility, as well as their unique optical and electrical properties. In particular, the electrical properties of CPs can be simply tuned over the full range from insulator to metal via a doping process, such as chemical, electrochemical, charge injection, and photo-doping. Over the past few decades, remarkable progress has been made in biomedical research including biosensors, tissue engineering, artificial muscles, and drug delivery, as CPs have been utilized as a key component in these fields. In this article, we review CPs from the perspective of biomedical engineering. Specifically, representative biomedical applications of CPs are briefly summarized: biosensors, tissue engineering, artificial muscles, and drug delivery. -

POLYMER-PLASTICS TECHNOLOGY and ENGINEERING June 1999 Aims and Scope

rJ 31 CY Ls dM F4 B cnY 0 cc z=8 OE 0 U POLYMER-PLASTICS TECHNOLOGY AND ENGINEERING June 1999 Aims and Scope. The joumal Polymer-Plastics Technology and Engineering will provide a forum for the prompt publication of peer-reviewed, English lan- guage articles such as state-of-the-art reviews, full research papers, reports, notes/communications, and letters on all aspects of polymer and plastics tech- nology that are industrial, semi-commercial, and/or research oriented. Some ex- amples of the topics covered are specialty polymers (functional polymers, liq- uid crystalline polymers, conducting polymers, thermally stable polymers, and photoactive polymers), engineering polymers (polymer composites, polymer blends, fiber forming polymers, polymer membranes, pre-ceramics, and reac- tive processing), biomaterials (bio-polymers, biodegradable polymers, biomed- ical plastics), applications of polymers (construction plastics materials, elec- tronics and communications, leather and allied areas, surface coatings, packaging, and automobile), and other areas (non-solution based polymerization processes, biodegradable plastics, environmentally friendly polymers, recycling of plastics, advanced materials, polymer plastics degradation and stabilization, natural, synthetic and graft polymerskopolymers, macromolecular metal com- plexes, catalysts for producing ultra-narrow molecular weight distribution poly- mers, structure property relations, reactor design and catalyst technology for compositional control of polymers, advanced manufacturing techniques and equipment, plastics processing, testing and characterization, analytical tools for characterizing molecular properties and other timely subjects). Identification Statement. Polymer-Plastics Technology and Engineering is pub- lished five times a year in the months of February, April, June, September, and November by Marcel Dekker, Inc., P.O. Box 5005, 185 Cimarron Road, Monti- cello, NY 12701-5185. -

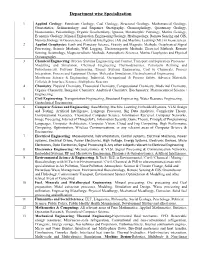

Department Wise Specialization

Department wise Specialization 1 Applied Geology: Petroleum Geology, Coal Geology, Structural Geology, Mathematical Geology, Geostatistics, Sedimentology and Sequence Stratigraphy, Geomorphology, Quaternary Geology, Neotectonics, Paleontology, Organic Geochemistry, Igneous, Metamorphic Petrology, Marine Geology, Economic Geology, Mineral Exploration, Engineering Geology, Hydrogeology, Remote Sensing and GIS, Nanotechnology in Geosciences, Artificial Intelligence (AI) and Machine Learning (ML) in Geosciences. 2 Applied Geophysics: Earth and Planetary Science, Gravity and Magnetic Methods, Geophysical Signal Processing, Seismic Methods, Well Logging, Electromagnetic Methods, Electrical Methods, Remote Sensing, Seismology, Magneto-telluric Methods, Atmospheric Sciences, Marine Geophysics and Physical Oceanography. 3 Chemical Engineering: Process Systems Engineering and Control, Transport and Separation Processes Modelling and Simulation, Chemical Engineering Thermodynamics, Petroleum Refining and Petrochemicals, Polymer Engineering, Energy Systems Engineering, Coal to Chemicals, Process Integration, Process and Equipment Design, Molecular Simulation, Electrochemical Engineering Membrane Science & Engineering, Industrial, Occupational & Process Safety, Advance Materials, Colloids & Interface Science, Multiphase Reactors 4 Chemistry: Physical Chemistry, Theoretical Chemistry, Computational Chemistry, Medicinal Chemistry, Organic Chemistry, Inorganic Chemistry, Analytical Chemistry, Biochemistry, Pharmaceutical Science / Engineering. 5 Civil -

Glossary of Materials Engineering Terminology

Glossary of Materials Engineering Terminology Adapted from: Callister, W. D.; Rethwisch, D. G. Materials Science and Engineering: An Introduction, 8th ed.; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, 2010. McCrum, N. G.; Buckley, C. P.; Bucknall, C. B. Principles of Polymer Engineering, 2nd ed.; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, 1997. Brittle fracture: fracture that occurs by rapid crack formation and propagation through the material, without any appreciable deformation prior to failure. Crazing: a common response of plastics to an applied load, typically involving the formation of an opaque banded region within transparent plastic; at the microscale, the craze region is a collection of nanoscale, stress-induced voids and load-bearing fibrils within the material’s structure; craze regions commonly occur at or near a propagating crack in the material. Ductile fracture: a mode of material failure that is accompanied by extensive permanent deformation of the material. Ductility: a measure of a material’s ability to undergo appreciable permanent deformation before fracture; ductile materials (including many metals and plastics) typically display a greater amount of strain or total elongation before fracture compared to non-ductile materials (such as most ceramics). Elastic modulus: a measure of a material’s stiffness; quantified as a ratio of stress to strain prior to the yield point and reported in units of Pascals (Pa); for a material deformed in tension, this is referred to as a Young’s modulus. Engineering strain: the change in gauge length of a specimen in the direction of the applied load divided by its original gauge length; strain is typically unit-less and frequently reported as a percentage. -

Novel PM Tool Steel with Improved Hardness and Toughness Faraz

cycle X XXI Doctoral School in Materials, Mechatronics and Systems Engineering Novel PM Tool Steel with improved hardness and toughness Faraz Deirmina September 2017 NOVEL PM TOOL STEEL WITH IMPROVED HARDNESS AND TOUGHNESS Faraz Deirmina E-mail: [email protected] Approved by: Ph.D. Commission: Prof. Massimo Pellizzari -, Advisor Prof. Alberto Molinari, Department of Industrial Engineering Department of Industrial Engineering University of Trento, Italy. University of Trento, Italy. Prof. Maurizio Vedani, Department of Mechanical Engineering Politecnico di Milano, Italy. Prof. Elena Gordo ODÉRIZ, Department of Materials Science and Engineering and Chemical Engineering University of Carlos III de Madrid, Spain. University of Trento, Department of Industrial Engineering September 2017 University of Trento - Department of - - - - - - - - - Doctoral Thesis Name - 2017 Published in Trento (Italy) – by University of Trento ISBN: - - - - - - - - - III To my wife, my comrade Camellia, and her adorable children Oblomov, Truffaut and Hugo IV Abstract Ultrafine grained (~ 1μm) steels have been the subject of extensive research work during the past years. These steels generally offer interesting perspectives looking for improved mechanical properties. UFG Powder Metallurgy hot work tool steels (HWTS) can be fabricated by high energy mechanical milling (MM) followed by spark plasma sintering (SPS). However, similarly to most UFG and Nano-Crystalline (NC) metals, reduced ductility and toughness result from the early plastic instabilities in these steels. Industrialization of UFG PM Tool Steels requires the application of specific metallurgical tailoring to produce tools with sound mechanical properties or in a more optimistic way, to break the Strength-Toughness “trade-off” in these materials. Among the possible ways proposed to restore ductility and toughness without losing the high strength, “Harmonic microstructure” design seems to be a very promising endeavor in this regard. -

Du Pont Family

GENEALOGY of the DU PONT FAMILY 1739-1949 Copyright 1943 by PIERRE S. DU PONT Designed and Printed by HAMBLETON COMPANY, INC. Wilmington, Delaware 1949 GENEALOGY of the DUPONT FAMILY HIS WORK is one of compilation only. Members of the du Pont family have furnished Tthe information necessary for complete and accurate results and have earned thereby the gratitude of their fellow members. To Henry A. du Pont we are indebted for the greater part of our information con cerning the generations of the family prior to the year 1739. His voluminous work UThe Early Generations of the Du Pont and Allied Families" is of inestimable value. The collection of the genealogical data in chart form was started by Coleman du Pont in cooperation with Ferdinand La Motte, Sr., more than twenty-five years ago. Much in formation was supplied from the photograph album of the du Pont £e,mily compiled by Louisa du Pont Copeland about 1900. This album was republished and brought up to date by William Winder Laird, Jr., in 1935. These workers deserve our thanks for their part in this undertaking. Bessie Gardner du Pont's interest and years of work in examining and translating letters and documents continues to hold fust place in its inspiration for continued study of family history. Much of the _present work is due to her example and to the accuracy of her pen. Much of the credit for securing the information necessary to make this revised edition of the genealogy as complete and up-to-date as possible is due to Miss Aileen du Pont, who has spent much time and effort in obtaining data from various branches of the family.