Woldeyesus Ammar, 1992. Eritrea, Root Causes of War and Refugees

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An Analysis of the Afar-Somali Conflict in Ethiopia and Djibouti

Regional Dynamics of Inter-ethnic Conflicts in the Horn of Africa: An Analysis of the Afar-Somali Conflict in Ethiopia and Djibouti DISSERTATION ZUR ERLANGUNG DER GRADES DES DOKTORS DER PHILOSOPHIE DER UNIVERSTÄT HAMBURG VORGELEGT VON YASIN MOHAMMED YASIN from Assab, Ethiopia HAMBURG 2010 ii Regional Dynamics of Inter-ethnic Conflicts in the Horn of Africa: An Analysis of the Afar-Somali Conflict in Ethiopia and Djibouti by Yasin Mohammed Yasin Submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree PHILOSOPHIAE DOCTOR (POLITICAL SCIENCE) in the FACULITY OF BUSINESS, ECONOMICS AND SOCIAL SCIENCES at the UNIVERSITY OF HAMBURG Supervisors Prof. Dr. Cord Jakobeit Prof. Dr. Rainer Tetzlaff HAMBURG 15 December 2010 iii Acknowledgments First and foremost, I would like to thank my doctoral fathers Prof. Dr. Cord Jakobeit and Prof. Dr. Rainer Tetzlaff for their critical comments and kindly encouragement that made it possible for me to complete this PhD project. Particularly, Prof. Jakobeit’s invaluable assistance whenever I needed and his academic follow-up enabled me to carry out the work successfully. I therefore ask Prof. Dr. Cord Jakobeit to accept my sincere thanks. I am also grateful to Prof. Dr. Klaus Mummenhoff and the association, Verein zur Förderung äthiopischer Schüler und Studenten e. V., Osnabruck , for the enthusiastic morale and financial support offered to me in my stay in Hamburg as well as during routine travels between Addis and Hamburg. I also owe much to Dr. Wolbert Smidt for his friendly and academic guidance throughout the research and writing of this dissertation. Special thanks are reserved to the Department of Social Sciences at the University of Hamburg and the German Institute for Global and Area Studies (GIGA) that provided me comfortable environment during my research work in Hamburg. -

The Geothermal Activity of the East African Rift

Presented at Short Course IV on Exploration for Geothermal Resources, organized by UNU-GTP, KenGen and GDC, at Lake Naivasha, Kenya, November 1-22, 2009. Kenya Electricity Generating Co., Ltd. GEOTHERMAL TRAINING PROGRAMME Geothermal Development Company THE GEOTHERMAL ACTIVITY OF THE EAST AFRICAN RIFT Peter A. Omenda Geothermal Development Company P. O. Box 100746, Nairobi 00101 KENYA [email protected] ABSTRACT The East Africa Rift System is a classical continental rift system associated with the world-wide mid ocean rift systems. The rift extends from the Red Sea – Afar triple junction through Ethiopian highlands, Kenya, Tanzania and Malawi to Mozambique in the south. The western branch passes through Uganda, DRC and Rwanda while the nascent south-western branch runs through Luangwa and Kariba rifts in Zambia into Botswana. The volcanic and tectonic activity in the rift started about 30 million years ago and in the eastern branch the activity involved faulting and eruption of large volumes of mafic and silicic lavas and pyroclastics. The western branch, typified by paucity of volcanism, is younger and dominated by faulting that has created deep basins currently filled with lakes and sediments. Geothermal activity in the rift is manifested by the occurrences of Quaternary volcanoes, hotsprings, fumaroles, boiling pools, hot and steaming grounds, geysers and sulphur deposits. The manifestations are abundant and stronger in the eastern branch that encompasses Afar, Ethiopian and Kenya rifts while in the western branch, the activity is subdued and occurs largely as hotsprings and fumaroles. Detailed and reconnaissance studies of geothermal potential in Eastern Africa indicates that the region has potential of 2,500MWe to 6,500MWe. -

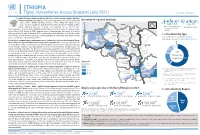

20210714 Access Snapshot- Tigray Region June 2021 V2

ETHIOPIA Tigray: Humanitarian Access Snapshot (July 2021) As of 31 July 2021 The conflict in Tigray continues despite the unilateral ceasefire announced by the Ethiopian Federal Government on 28 June, which resulted in the withdrawal of the Ethiopian National Overview of reported incidents July Since Nov July Since Nov Defense Forces (ENDF) and Eritrea’s Defense Forces (ErDF) from Tigray. In July, Tigray forces (TF) engaged in a military offensive in boundary areas of Amhara and Afar ERITREA 13 153 2 14 regions, displacing thousands of people and impacting access into the area. #Incidents impacting Aid workers killed Federal authorities announced the mobilization of armed forces from other regions. The Amhara region the security of aid Tahtay North workers Special Forces (ASF), backed by ENDF, maintain control of Western zone, with reports of a military Adiyabo Setit Humera Western build-up on both sides of the Tekezi river. ErDF are reportedly positioned in border areas of Eritrea and in SUDAN Kafta Humera Indasilassie % of incidents by type some kebeles in North-Western and Eastern zones. Thousands of people have been displaced from town Central Eastern these areas into Shire city, North-Western zone. In line with the Access Monitoring and Western Korarit https://bit.ly/3vcab7e May Reporting Framework: Electricity, telecommunications, and banking services continue to be disconnected throughout Tigray, Gaba Wukro Welkait TIGRAY 2% while commercial cargo and flights into the region remain suspended. This is having a major impact on Tselemti Abi Adi town May Tsebri relief operations. Partners are having to scale down operations and reduce movements due to the lack Dansha town town Mekelle AFAR 4% of fuel. -

Post-Colonial Journeys: Historical Roots of Immigration Andintegration

Post-Colonial Journeys: Historical Roots of Immigration andIntegration DYLAN RILEY AND REBECCA JEAN EMIGH* ABSTRACT The effect ofItalian colonialismon migration to Italy differedaccording to the pre-colonialsocial structure, afactor previouslyneglected byimmigration theories. In Eritrea,pre- colonialChristianity, sharp class distinctions,and a strong state promotedinteraction between colonizers andcolonized. Eritrean nationalismemerged against Ethiopia; thus, nosharp breakbetween Eritreans andItalians emerged.Two outgrowths ofcolonialism, the Eritrean nationalmovement andreligious ties,facilitate immigration and integration. In contrast, in Somalia,there was nostrong state, few class differences, the dominantreligion was Islam, andnationalists opposed Italian rule.Consequently, Somali developed few institutionalties to colonialauthorities and few institutionsprovided resources to immigrants.Thus, Somaliimmigrants are few andare not well integratedinto Italian society. * Direct allcorrespondence to Rebecca Jean Emigh, Department ofSociology, 264 HainesHall, Box 951551,Los Angeles, CA 90095-1551;e-mail: [email protected]. ucla.edu.We would like to thank Caroline Brettell, RogerWaldinger, and Roy Pateman for their helpfulcomments. ChaseLangford made the map.A versionof this paperwas presentedat the Tenth International Conference ofEuropeanists,March 1996.Grants from the Center forGerman andEuropean Studies at the University ofCalifornia,Berkeley and the UCLA FacultySenate supported this research. ComparativeSociology, Volume 1,issue 2 -

The Genesis of the Modern Eritrean Struggle (1942–1961) Nikolaos Biziouras Published Online: 14 Apr 2013

This article was downloaded by: [US Naval Academy] On: 25 June 2013, At: 06:09 Publisher: Routledge Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office: Mortimer House, 37-41 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH, UK The Journal of the Middle East and Africa Publication details, including instructions for authors and subscription information: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/ujme20 The Genesis of the Modern Eritrean Struggle (1942–1961) Nikolaos Biziouras Published online: 14 Apr 2013. To cite this article: Nikolaos Biziouras (2013): The Genesis of the Modern Eritrean Struggle (1942–1961), The Journal of the Middle East and Africa, 4:1, 21-46 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/21520844.2013.771419 PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE Full terms and conditions of use: http://www.tandfonline.com/page/terms-and-conditions This article may be used for research, teaching, and private study purposes. Any substantial or systematic reproduction, redistribution, reselling, loan, sub-licensing, systematic supply, or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden. The publisher does not give any warranty express or implied or make any representation that the contents will be complete or accurate or up to date. The accuracy of any instructions, formulae, and drug doses should be independently verified with primary sources. The publisher shall not be liable for any loss, actions, claims, proceedings, demand, or costs or damages whatsoever or howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection -

Homeland, Identity and Wellbeing Amongst the Beni-Amer in Eritrea-Sudan and Diasporas

IM/MOBILITY: HOMELAND, IDENTITY AND WELLBEING AMONGST THE BENI-AMER IN ERITREA-SUDAN AND DIASPORAS Thesis Submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy at the University of Leicester Saeid Hmmed BSc MSc (OU) Department of Geography University of Leicester September 2017 i Abstract This thesis focuses on how mobility, identity, conceptions of homeland and wellbeing have been transformed across time and space amongst the Beni-Amer. Beni-Amer pastoralist societies inhabit western Eritrea and eastern Sudan; their livelihoods are intimately connected to livestock. Their cultural identities, norms and values, and their indigenous knowledge, have revolved around pastoralism. Since the 1950s the Beni-Amer have undergone rapid and profound socio-political and geographic change. In the 1950s the tribe left most of their ancestral homeland and migrated to Sudan; many now live in diasporas in Western and Middle Eastern countries. Their mobility, and conceptions of homeland, identity and wellbeing are complex, mutually constitutive and cannot be easily untangled. The presence or absence, alteration or limitation of one of these concepts affects the others. Qualitatively designed and thematically analysed, this study focuses on the multiple temporalities and spatialities of Beni-Amer societies. The study subjected pastoral mobility to scrutiny beyond its contemporary theoretical and conceptual framework. It argues that pastoral mobility is currently understood primarily via its role as a survival system; as a strategy to exploit transient concentration of pasture and water across rangelands. The study stresses that such perspectives have contributed to the conceptualization of pastoral mobility as merely physical movement, a binary contrast to settlement; pastoral societies are therefore seen as either sedentary or mobile. -

Changing Security:Theoretical and Practical Discussions

Durham E-Theses Changing Security:Theoretical and Practical Discussions. The Case of Lebanon. SMAIRA, DIMA How to cite: SMAIRA, DIMA (2014) Changing Security:Theoretical and Practical Discussions. The Case of Lebanon. , Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/10810/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk 2 Changing Security: Theoretical and Practical Discussions. The Case of Lebanon. Dima Smaira Thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in International Relations. School of Government and International Affairs Durham University 2014 i Abstract This study is concerned with security; particularly security in Lebanon. It is also equally concerned with various means to improve security. Building on debates at the heart of world politics and Security Studies, this study first discusses trends in global governance, in the study of security, and in security assistance to post-conflict or developing countries. -

Kjeik Ibrahim Sultan Ali

Remembering unique Eritreans in contemporary history A short biographical sketch Of Kjeik Ibrahim Sultan Ali Ibrahim Sultan in 1965 Source: google.com Compiled and edited from electronic sources By Kidane Mehari Nashi Oslo, Norway June 2013 Table of content Early life Ibrahim Sultan: Working life British Administration of Eritrea followed by Federation with Ethiopia Political activities: Formation of Al Rabita Al Islamia At the United Nations Waala Biet Ghiorgis Historic contributions of Kjekk Ibrahim Sultan Ali Exile and participation in armed struggle End of life – two years before independence Early life Ibrahim Sultan Ali (1909-1987) was one of the original proponents of the Eritrean Independence movement. Ibrahim was born in the city of Keren where he was educated in Islamic and Italian schools. He worked closely with Woldeab Woldemariam before the Federation with Ethiopia to secure Eritrean Independence. He was the founder of the Eritrean Moslem League. Birth and family: Ibrahim Sultan Ali was born in Keren in March 1909 of a farmer/trader Tigre/serf from the Rugbat of Ghizghiza district in Sahel. He attended Quran School under Khalifa Jaafer of the Halanga of Kassala. In Keren, he attended technical training at Salvaggio Raggi and at Umberto School in Asmara. His only son Abdulwahab, lives in Paris. Ibrahim Sultan: Working life Joining the Eritrean Rail Ibrahim Sultan worked as a chief conductor from 1922 to 1926. From 1926 to 1941, he was head of Islamic Affairs section under Italian rule. Served as civil servant in Keren, Agordat, Tessenei, Adi Ugri and even Wiqro near Mekele for six months. -

Overview of Geothermal Resource Utilization and Potential in East African Rift System

Presented at Short Course II on Surface Exploration for Geothermal Resources, organized by UNU-GTP and KenGen, at Lake Naivasha, Kenya, 2-17 November, 2007. GEOTHERMAL TRAINING PROGRAMME Kenya Electricity Generating Co., Ltd. OVERVIEW OF GEOTHERMAL RESOURCE UTILIZATION AND POTENTIAL IN EAST AFRICAN RIFT SYSTEM Meseret Teklemariam Ministry of Mines and Energy Geological Survey of Ethiopa Addis Ababa ETHIOPIA [email protected] ABSTRACT The Great East African Rift System (EARS) is one of the major tectonic structures of the earth that extends for about 6500 km from the Middle East (Dead Sea-Jordan Valley) in the North to Mozambique in the south (Figure 1). This system consists of three main arms: the Red Sea Rift; the Gulf of Aden Rift; and the East African Rift which develops through Eritrea, Ethiopia, Kenya, Tanzania, Zambia, Malawi and northern Mozambique floored by a thinned continental crust. The EARS is composed of two rift trends; the eastern and western branches. The western branch develops from Uganda throughout Lake Tanganyika, where it joins the Eastern branch, following the border between Rwanda and Zaire. The western branch is, however, much less active in terms of volcanism although both branches are seismically and tectonically active today. The East African Rift is one of the most important zones of the world where the heat energy of the interior of the Earth escapes to the surface in the form of volcanic eruptions, earthquakes and the upward transport of heat by hot springs and natural vapor emanations (fumaroles). As a consequence, the EARS appears to possess a remarkable geothermal potential. -

The Global State of Lgbtiq Organizing

THE GLOBAL STATE OF LGBTIQ ORGANIZING THE RIGHT TO REGISTER Written by Felicity Daly DrPH Every day around the world, LGBTIQ people’s human rights and dignity are abused in ways that shock the conscience. The stories of their struggles and their resilience are astounding, yet remain unknown—or willfully ignored—by those with the power to make change. OutRight Action International, founded in 1990 as the International Gay and Lesbian Human Rights Commission, works alongside LGBTIQ people in the Global South, with offices in six countries, to help identify community-focused solutions to promote policy for lasting change. We vigilantly monitor and document human rights abuses to spur action when they occur. We train partners to expose abuses and advocate for themselves. Headquartered in New York City, OutRight is the only global LGBTIQ-specific organization with a permanent presence at the United Nations in New York that advocates for human rights progress for LGBTIQ people. [email protected] https://www.facebook.com/outrightintl http://twitter.com/outrightintl http://www.youtube.com/lgbthumanrights http://OutRightInternational.org/iran OutRight Action International 80 Maiden Lane, Suite 1505, New York, NY 10038 U.S.A. P: +1 (212) 430.6054 • F: +1 (212) 430.6060 This work may be reproduced and redistributed, in whole or in part, without alteration and without prior written permission, solely for nonprofit administrative or educational purposes provided all copies contain the following statement: © 2018 OutRight Action International. This work is reproduced and distributed with the permission of OutRight Action International. No other use is permitted without the express prior written permission of OutRight Action International. -

UN/US Sanctions on Eritrea: Latest Chapter in a Long History of Injustice

600 L St., NW, Suite 200 | Washington, DC 20001 | www.eritrean-smart.org | INFO@ Eritrean-Smart.org UUNN//UUSS SSaannccttiioonnss oonn EErriittrreeaa:: LLaatteesstt CChhaapptteerr iinn aa LLoonngg HHiissttoorryy ooff IInnjjuussttiiccee Eritrean-SMART Campaign Working Paper No. 2 By the E-SMART Research Team December 23, 2010 http://www.eritrean-smart.org Support our Worldwide E-SMART Campaign Eritrean Sanctions Must be Annulled and Repealed Today! Contents Executive Summary ................................................................................................................................. 3 INTRODUCTION ....................................................................................................................................... 4 Part I: A HISTORY OF BETRAYALS ............................................................................................................. 6 Denial of Right to Self‐Determination and Independence ........................................................................... 6 A Sham Federal Arrangement ...................................................................................................................... 7 OAU’s Refusal to Address the Plight of the Eritrean People ........................................................................ 8 U.S. Support of Ethiopia during Eritrea’s War of Independence .................................................................. 8 Efforts to Make Eritreans Settle for Something Short of Independence .................................................... -

Eastern Nile Technical Regional Office

. EASTERN NILE TECHNICAL REGIONAL OFFICE TRANSBOUNDARY ANALYSIS FINAL COUNTRY REPORT ETHIOPIA September 2006 This report was prepared by a consortium comprising Hydrosult Inc (Canada) the lead company, Tecsult (Canada), DHV (The Netherlands) and their Associates Nile Consult (Egypt), Comatex Nilotica (Sudan) and A and T Consulting (Ethiopia) DISCLAIMER The maps in this Report are provided for the convenience of the reader. The designations employed and the presentation of the material in these maps do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Eastern Nile Technical Office (ENTRO) concerning the legal or constitutional status of any Administrative Region, State or Governorate, Country, Territory or Sea Area, or concerning the delimitation of any frontier. WATERSHED MANAGEMENT CRA CONTENTS DISCLAIMER ........................................................................................................ 2 LIST OF ACRONYMS AND ABBREVIATIONS .................................................. viii EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ...................................................................................... x 1. BACKGROUND ................................................................................................ 1 1.1 Introduction ............................................................................................. 1 1.2 Primary Objectives of the Watershed Management CRA ....................... 2 1.3 The Scope and Elements of Sustainable Watershed Management ........ 4 1.3.1 Watersheds and River Basins 4