Intersections

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CHARM 2019 Program

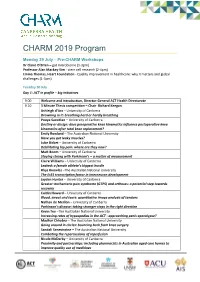

CHARM 2019 Program Monday 29 July – Pre-CHARM Workshops Dr Claire O’Brien – gut microbiome (1-3pm) Professor Alan Mackay-Sim - stem cell research (2-4pm) Emma Thomas, Heart Foundation - Quality improvement in healthcare: why it matters and global challenges (1-3pm) Tuesday 30 July Day 1: ACT in profile – big initiatives 9.00 Welcome and introduction, Director-General ACT Health Directorate 9.10 3 Minute Thesis competition – Chair Richard Keegan Ashleigh d’Arx – University of Canberra Drowning in it: breathing hard or hardly breathing Pouya Saeedian – University of Canberra Destiny or design: does preoperative knee kinematics influence postoperative knee kinematics after total knee replacement? Emily Rowland – The Australian National University Have you got leaky muscles? Luke Bicket – University of Canberra Debilitating hip pain: where are they now? Matt Boom – University of Canberra Staying strong with Parkinson’s – a matter of measurement Claire Williams – University of Canberra Leaked: a female athlete’s biggest hurdle Rhys Knowles –The Australian National University The Er81 transcription factor in interneuron development Jayden Hunter – University of Canberra Greater trochanteric pain syndrome (GTPS) and orthoses: a potential step towards recovery Caitlin Howard – University of Canberra Blood, sweat and tears: quantitative image analysis of tendons Nathan de Meillon – University of Canberra Parkinson’s disease: taking stronger steps in the right direction Kevin Tee –The Australian National University Increasing rates of hypospadias -

Chapter 5 Analysis

Copyright by Fanny Macé 2019 The Dissertation Committee for Fanny Macé certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: #PRÉSIDENTIELLE2017 A CRITICAL DISCOURSE ANALYSIS OF THE 2017 FRENCH PRESIDENTIAL CAMPAIGN ON TWITTER Committee: Carl S. Blyth, Supervisor David P. Birdsong Barbara E. Bullock Elizabeth L. Keating #PRÉSIDENTIELLE2017 A CRITICAL DISCOURSE ANALYSIS OF THE 2017 FRENCH PRESIDENTIAL CAMPAIGN ON TWITTER by Fanny Macé Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin May 2019 Dedication To the memory of my father, Pascal Macé (1957-1997) Acknowledgements Thank you to my advisor, Carl Blyth, for placing his faith in me and in my ability to complete this project. Thank you to my committee, Elizabeth Keating, Barbara Bullock and David Birdsong, for accompanying me along this journey. Thank you to Jessica Luhn, for being always helpful and supportive. Thank you to my students, for brightening my days and perpetuating my love for teaching. Thank you to my friends, in Austin and all around the world, for believing in me even when I didn’t. Thank you to my family, for their love and support, even from thousands of miles away. Thank you to my fiancé, Justin Gannon, for keeping me sane and for being so patient with me, even during my daily rants about politics. Special thanks to our two cats, Zumi and Willow, for their adorableness and comforting presence. Finally, thank you to coffee, for keeping me alive and awake. -

Department of the Arts, Sport and Recreation Annual Report 2005–06

Department of the Arts, Sport and Recreation Annual Report 2005-06 Cover image The Grand Cricket Match, attributed to ST Gill, 1862. Courtesy of State Library of NSW, www.atmitchell.com The Hon R J Debus, MP Attorney General Contents Minister for the Environment Minister for the Arts Overview 2 Level 36, Governor Macquarie Tower Who we are 2 1 Farrer Place SYDNEY NSW 2000 What we do 2 Our stakeholders 2 The Hon G A McBride, MP Minister for Gaming and Racing Framework 3 Minister for the Central Coast Director-General’s report – highlights Level 35, Governor Macquarie Tower 2005-06 and the year ahead 4 1 Farrer Place SYDNEY NSW 2000 Financial position 8 Corporate governance 9 The Hon S C Nori, MP Minister for Tourism and Sport and Recreation Review of operations Minister for Women Arts NSW 12 Minister Assisting the Minister for State Development Level 34, Governor Macquarie Tower Operating environment 12 1 Farrer Place Performance review 15 SYDNEY NSW 2000 Review of operations NSW Office of Liquor, Gaming and Racing 28 Dear Ministers Operating environment 28 Performance review 28 It is my pleasure to submit to you, for presentation to Parliament, the Department of the Arts, Sport and Recreation’s Review of operations Annual Report for the year ended 30 June, 2006. NSW Sport and Recreation 42 The annual report, in my opinion, has been prepared in full Operating environment 42 compliance with the requirements of the Annual Reports (Departments) Act 1985, the Annual Reports (Departments) Performance review 44 Regulation 2005 and the Public Finance and Audit Act 1983. -

Language Use and Translation a Festschrift for Erich Steiner This Book Celebrates Erich Steiner’S Scholarly Work

caught in the middle cover_Layout 1 04.04.2014 11:42 Seite 1 Caught in the Middle – Language Use and Translation A Festschrift for Erich Steiner This book celebrates Erich Steiner’s scholarly work. In 25 th contributions, colleagues and friends take up issues on the Occasion of his 60 Birthday closely related to his research interests in linguistics and translation studies. The result is a colourful kaleidoscope reflecting the many strands of research questions that Erich Steiner helped advance in the past decades and the Edited by cheerful, inspiring atmosphere he continues to create. n o i t Kerstin Kunz a l s n a Elke Teich r T d n Silvia Hansen Schirra a - e s U Stella Neumann e g a u Peggy Daut g n a L – e l d d i M e h t n i t h g u a C universaar Universitätsverlag des Saarlandes Saarland University Press Presses Universitaires de la Sarre Kerstin Kunz, Elke Teich, Silvia Hansen -Schirra, Stella Neumann, Peggy Daut (eds.) Caught in the Middle – Language Use and Translation A Festschrift for Erich Steiner on the Occasion of his 60th Birthday universaar Universitätsverlag des Saarlandes Saarland University Press Presses Universitaires de la Sarre © 2014 universaar Universitätsverlag des Saarlandes Saarland University Press Presses Universitaires de la Sarre Postfach 151150, 66041 Saarbrücken ISBN 978-3-86223-144-7 gedruckte Ausgabe ISBN 978-3-86223-145-4 Online-Ausgabe URN urn:nbn:de:bsz:291-universaar-1225 Projektbetreuung universaar : Susanne Alt, Matthias Müller Satz: Waldemar Kasdorf Umschlaggestaltung: Julian Wichert Gedruckt auf säurefreiem Papier von Monsenstein & Vannerdat Bibliografische Information der Deutschen Nationalbibliothek: Die Deutsche Nationalbibliothek verzeichnet diese Publikation in der Deutschen National bibliografie; detaillierte bibliografische Daten sind im Internet über <http://dnb.d-nb.de> abrufbar. -

“Linguistic Perspectives on Humour”

COLLOQUIUM OF THE AUSTRALASIAN HUMOUR SCHOLARS NETWORK AT UNSW, SYDNEY “LINGUISTIC PERSPECTIVES ON HUMOUR” Saturday 6th April 2002 (9.00 a.m. – 4.30 p.m.) Australian Graduate School of Management Building (AGSM), UNSW (Tel: (02) 9931 9200. Entry: Gate 11, Botany St, Randwick; collect parking voucher if needed from the AGSM Front Desk on arrival and proceed to Parking Station’s upper floors for parking) CONVENOR AND CHAIR: JESSICA MILNER DAVIS PROGRAMME AND ABSTRACTS OF PRESENTATIONS 1 TIMETABLE 9.00 – 9.25 Registration Tea and Coffee 9.25 – 10.15 Dr Graeme Ritchie, Division of Informatics, University of Edinburgh; “The Linguistic Analysis of Jokes” 10.15 – 11.05 Meredith Marra, Language in the Workplace Project, Victoria University of Wellington, N.Z.; “Punch-lines, Jab lines and Workplace Anecdotes” 11.05 – 11.30 Morning Refreshments 11.30 – 12.20 Dr Suzanne Eggins, Head, School of English, UNSW; “Analysing and Theorizing Humour in Children’s Prize-winning Creative Writing Texts” 12.20 – 1.10 Dr Marguerite Wells, Author, Japanese Humour; “Linguistic Concepts and Terms for Humour in Japanese and English” 1.10 – 2.00 Lunch 2.00 – 2.15 Moses Bainy, Author, Why Do We Laugh and Cry?; “Humour and Laughter and the Theory of Values” 2.15 – 2.30 Dr Graeme Ritchie; “Commentary on Linguistic Theories of Humour” 2.30 – 3.30 Plenary Discussion 3.30 Close ABSTRACTS “The Linguistic Analysis of Jokes” Graeme Ritchie Leverhulme Research Fellow Division of Informatics University of Edinburgh To tackle the vast and complex task of devising a theory of humour, it is methodologically desirable to find manageably small problems which are substantial enough to be of theoretical interest. -

A Systemic Functional Approach to Applied Linguistic Article Conclusions

A Systemic Functional Approach to Applied Linguistic Article Conclusions by Viktoria Volkova A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate and Postdoctoral Affairs in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Applied Linguistics and Discourse Studies Carleton University Ottawa, Ontario ©2012 Viktoria Volkova Library and Archives Bibliotheque et Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du 1+1 Branch Patrimoine de I'edition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A0N4 Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-93617-7 Our file Notre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-93617-7 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non L'auteur a accorde une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library and permettant a la Bibliotheque et Archives Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par telecommunication ou par I'lnternet, preter, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des theses partout dans le loan, distrbute and sell theses monde, a des fins commerciales ou autres, sur worldwide, for commercial or non support microforme, papier, electronique et/ou commercial purposes, in microform, autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L'auteur conserve la propriete du droit d'auteur ownership and moral rights in this et des droits moraux qui protege cette these. Ni thesis. Neither the thesis nor la these ni des extraits substantiels de celle-ci substantial extracts from it may be ne doivent etre imprimes ou autrement printed or otherwise reproduced reproduits sans son autorisation. -

Analysing Language Use in Work, Education, Medical and Museum Contexts

Iperstoria – Testi Letterature Linguaggi www.iperstoria.it Rivista semestrale ISSN 2281-4582 Language at Work: Analysing Language Use in Work, Education, Medical and Museum Contexts Edited by Helen de Silva Joyce Newcastle upon Tyne, Cambridge Scholar Publishing, 2016, pp. 277 Review by Erik Castello The volume Language at Work explores the language used in a variety of workplace contexts ranging from call centres through secondary schools and hospitals to museums. Written, spoken and/or multimodal texts are analysed, with a view to investigating how professionals communicate with their colleagues, costumers, students, patients or visitors. The majority of the thirteen contributions concern private or public contexts in Australia. Eleven of them draw on the theoretical framework of Systemic Functional Linguistics (SFL) and make extensive reference to Michael Halliday’s work as well as to that of scholars working within the SFL tradition. Two studies adopt altogether different methodological approaches, while others combine SFL with other methods, including Conversation Analysis, Language Testing and Ethnographic and Literacy Studies. The book consists of four parts. Part 1 refers to three different workplace contexts, Part 2 to education contexts, Part 3 to medical contexts and Part 4 to museum contexts. Part 1 starts off with Jane Lockwood’s study of how personnel is recruited by call centres in various parts of Asia to provide services to bank customers who live in English-speaking countries. It reports on the development and revision of the procedures followed to assess the candidates’ level of English and communication skills. The author first describes the Business Performance Language Assessment System (BUPLAS), which incorporates a set of criteria that focus on linguistic, interactional and strategic aspects of communication. -

I See What You Mean Using Spoken Discource in the Classroom

cover 1 10/10/08 10:45 AM Page 1 ‘I mean’ see what you ‘I This practical and accessible handbook encourages teachers of language and literacy to examine why using authentic spoken discourse in the classroom benefits second language learners. It gives them clear guidelines on how do this as part of their own teaching program. see The book derives from the Spoken Discourse Project conducted through NCELTR, whose main aim was to increase knowledge and understanding of how authentic language could be used in teaching. ‘I see what you mean’ contains: what • a useful introduction to current key theoretical approaches to spoken discourse analysis • a study of the implications of ethnographic research into spoken language use • advice on how to collect and transcribe samples of spoken language you comparisons of scripted spoken dialogues with natural samples of language • sample analyses of data as models of how to analyse spoken language data • guidelines for incorporating spoken discourse into teaching frameworks for analysing learner needs and structuring units of work The book is an excellent, accessible introduction to the field, and uses a mean’ practical task and case study approach. Burns, Joyce, Gollin Anne Burns is Senior Lecturer in Linguistics at Macquarie University and Using spoken Coordinator of the Publications Development section at NCELTR. Helen Joyce works in Program Support and Development Services in the discourse in NSW Adult Migrant English Service and lectures at the University of Technology, Sydney the classroom: Sandra Gollin is a lecturer in Linguistics at Macquarie University. Her research interests include spoken and written discourse analysis and English a handbook for academic and professional purposes. -

Canberra Langfest 2011

canberra langfest 2011 Applied Linguistics Association of Australia (ALAA) Applied Linguistics Association of New Zealand (ALANZ) Australian Linguistic Society (ALS) Conferences Handbook November & December 2011, Canberra 1 Events 30 November – 2 December 2011 Applied Linguistics as a Meeting Place 2nd Combined Conference of the Applied Linguistics Association of Australia (ALAA) and Applied Linguistics Association of New Zealand (ALANZ) 29 November 2011 1st ALAA-ALANZ Postgraduate Student Workshop 30 November – 2 December 2011 1st Formal Meeting of the Association for Language Testing and Assessment of Australia and New Zealand (ALTAANZ) 1 and 2 December 2011 Special event: Language and the Law 1–4 December 2011 Australian Linguistics Society (ALS) 2011 Conference 3 December 2011 Canberra Languages Education Mini-Conference 2011 University of Canberra and The Australian National University 3 and 4 December 2011 Gamilaraay Language Teaching and Learning Workshop 5–9 December 2011 ALS Master Classes The Australian National University Kioloa Campus 2 Handbook Overview Part 1 USEFUL INFORMATION FOR ALAA-ALANZ AND ALS DELEGATES > Conference Venues. 7 > Coffee Meeting Places on Both Campuses. 8 > Internet Access for Delegates. 9 > Security . 9 > Smoking Policy. 9 > Langfest Sponsors. 10 > Langfest Exhibits. 10 > Restaurants in Canberra. 11 > What’s on in Canberra. 13 > Transport in Canberra. 14 Part 2 ALAA-ALANZ CONFERENCE(S) 30 November – 2 December 2011 17 Applied Linguistics as a Meeting Place 2nd Combined Conference of the Applied Linguistics -

36Th International Systemic Functional Congress 11Th China Functional

Tsinghua University Challenges to Systemic Functional Linguistics: Theory and Practice 36 th International Systemic Functional Congress 11 th China Functional Linguistics Conference 14-18 July 2009 Tsinghua University Beijing, China http://rwxy.tsinghua.edu.cn/36isfc 1 Contents Conference Welcome Sponsors Program Useful Information Maps Abstracts 2 Welcome and Gratitude The Organization Committee would like to extend our warmest welcome to all the participants of the 36 th International Systemic Functional Congress. Thank you for sending over your papers and for organizing the colloquia. We are certain that all of you will have a new experience and a rewarding time in Beijing. We also wish to express our heartfelt thanks to the members of the Executive Committee of the International Systemic Functional Association, to our collaborator, City University of Hong Kong, and to all the sponsors for their support to the congress, particularly Ministry of Education of the People’s Republic of China and our colleagues of Higher Education Press, who have greatly assisted the convention of the congress. th The members of The 36 ISFC Local Organizing Committee and Local Program Committee are: • The Local Organizing Committee: Chair: Fang Yan, Vice Chair: Li Zuowen; members: Lv Zhongshe, Fan Wenfang, Shu Xiaomei, Liu Nannan, , Li Shuman, Lu Xiuxia • The Local Program Committee: Chair: Luo Lisheng, Vice Chair: Liu Longgen; members: Liu Shisheng, Feng Zongxin, Huang Guowen, Wang Zhenhua, Peng Xuanwei FANG Yan Convenor of the 36 th International Systemic Functional Congress Department of Foreign Languages, Tsinghua University, Beijing, 10084, P.R. China [email protected] 36ISFC Sponsors Ministry of Education of the People’s Republic of China Higher Education Press (Group) under Ministry of Education P.R. -

Transitivity Analysis of Election Coverage in Online Newspapers Of

Asad, S., Mohd Noor, S.N.F., Jaes, L. /Vol. 8 Núm. 21: 168- 176/ Julio - agosto 2019 168 Artículo de investigación Transitivity Analysis of Election Coverage in Online Newspapers of Malaysia & Pakistan: A Study with Critical Discourse Analysis & Systematic Functional Linguistics’ Perspective Análisis de la transitividad de la cobertura electoral en los periódicos en línea de Malasia y Pakistán: un estudio con análisis crítico del discurso y una perspectiva sistemática de la lingüística funcional Análise da Transitividade da Cobertura Eleitoral em Jornais On-line da Malásia e Paquistão: Um Estudo com Análise Crítica do Discurso e Perspectiva da Linguística Sistemática Funcional Recibido: 24 de mayo del 2019 Aceptado: 29 de junio del 2019 Written by: Saira Asad (Corresponding author)55 Siti Noor Fazelah Binti Mohd Noor56 Lutfan Bin Jaes57 Abstract Resumen The language of the newspaper is emerged by El lenguaje del periódico surge de las creencias, beliefs, speech and writing practices (Joseph, el habla y las prácticas de escritura (Joseph, 2006). To analyze the hidden meaning behind the 2006). Para analizar el significado oculto detrás newspapers’ text of election span 2018 in del texto de los periodos electorales de 2018 en Malaysia and Pakistan, Norman Fairclough Malasia y Pakistán, Norman Fairclough (1995) (1995) theory of Critical Discourse Analysis Teoría del análisis crítico del discurso (CDA) se (CDA) is applied on news reports of aplica a los informes de noticias de ‘Malaysiakini’, ‘The New Straits Times’ 'Malaysiakini', 'The New Straits Times' (independent and mainstream online newspapers (independiente y los principales periódicos en from Malaysia), ‘Dawn’ and ‘The News’ (as línea de Malasia), 'Dawn' y 'The News' (como independent and mainstream online newspapers periódicos en línea independientes y from Pakistan). -

LING21505: Discourse Analysis Half Year 2 | Nottingham Trent University

09/26/21 LING21505: Discourse Analysis Half Year 2 | Nottingham Trent University LING21505: Discourse Analysis Half Year View Online 2 124 items Essential Text (1 items) Discourse analysis: an introduction - Brian Paltridge, 2012 Book Core module texts (7 items) Discourse Analysis - Barbara Johnstone, 2008 Book | Core Text Working with spoken discourse - Deborah Cameron, MyiLibrary, 2001 Book | Core Text Analysing discourse: textual analysis for social research - Norman Fairclough, MyiLibrary, 2003 Book | Core Text Methods of critical discourse analysis - Ruth Wodak, Michael Meyer, 2009 Book | Core Text Text and discourse analysis - Raphael Salkie, ebrary, Inc, 1995 Book | Core Text The discourse reader - 2014 Book | Core Text The handbook of discourse analysis - Deborah Schiffrin, Deborah Tannen, Heidi Ehernberger Hamilton, Wiley InterScience (Online service), 2005,2003 Book | Core Text Journals (4 items) You should refer to the following journals regularly Discourse Analysis Online (DAOL) Journal Discourse & Society Journal Critical Discourse Studies 1/9 09/26/21 LING21505: Discourse Analysis Half Year 2 | Nottingham Trent University Journal Discourse studies Journal Weekly Reading (11 items) These are the chapters you should read each week in preparation for lectures and seminars Week 2 - Analysing Written Discourse (1 items) Discourse analysis: an introduction - Brian Paltridge, 2012 Book | Core Text | Read Chapters 4 & 6 - 'Discourse and Genre' and 'Discourse Grammar' Week 3 - Analysing Spoken Discourse (1 items) Discourse analysis: