Second Language Reading and Instruction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Similarities and Differences Between Simultaneous and Successive Bilingual Children: Acquisition of Japanese Morphology

International Journal of Applied Linguistics & English Literature E-ISSN: 2200-3452 & P-ISSN: 2200-3592 www.ijalel.aiac.org.au Similarities and Differences between Simultaneous and Successive Bilingual Children: Acquisition of Japanese Morphology Yuki Itani-Adams1, Junko Iwasaki2, Satomi Kawaguchi3* 1ANU College of Asia & the Pacific, The Australian National University, Canberra, ACT, 2601, Australia 2School of Arts and Humanities, Edith Cowan University, 2 Bradford Street, Mt Lawley WA 6050, Australia 3School of Humanities and Communication Arts, Western Sydney University, Bullecourt Ave, Milperra NSW 2214, Australia Corresponding Author: Satomi Kawaguchi , E-mail: [email protected] ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Article history This paper compares the acquisition of Japanese morphology of two bilingual children who had Received: June 14, 2017 different types of exposure to Japanese language in Australia: a simultaneous bilingual child Accepted: August 14, 2017 who had exposure to both Japanese and English from birth, and a successive bilingual child Published: December 01, 2017 who did not have regular exposure to Japanese until he was six years and three months old. The comparison is carried out using Processability Theory (PT) (Pienemann 1998, 2005) as a Volume: 6 Issue: 7 common framework, and the corpus for this study consists of the naturally spoken production Special Issue on Language & Literature of these two Australian children. The results show that both children went through the same Advance access: September 2017 developmental path in their acquisition of the Japanese morphological structures, indicating that the same processing mechanisms are at work for both types of language acquisition. However, Conflicts of interest: None the results indicate that there are some differences between the two children, including the rate Funding: None of acquisition, and the kinds of verbal morphemes acquired. -

Part 1: Introduction to The

PREVIEW OF THE IPA HANDBOOK Handbook of the International Phonetic Association: A guide to the use of the International Phonetic Alphabet PARTI Introduction to the IPA 1. What is the International Phonetic Alphabet? The aim of the International Phonetic Association is to promote the scientific study of phonetics and the various practical applications of that science. For both these it is necessary to have a consistent way of representing the sounds of language in written form. From its foundation in 1886 the Association has been concerned to develop a system of notation which would be convenient to use, but comprehensive enough to cope with the wide variety of sounds found in the languages of the world; and to encourage the use of thjs notation as widely as possible among those concerned with language. The system is generally known as the International Phonetic Alphabet. Both the Association and its Alphabet are widely referred to by the abbreviation IPA, but here 'IPA' will be used only for the Alphabet. The IPA is based on the Roman alphabet, which has the advantage of being widely familiar, but also includes letters and additional symbols from a variety of other sources. These additions are necessary because the variety of sounds in languages is much greater than the number of letters in the Roman alphabet. The use of sequences of phonetic symbols to represent speech is known as transcription. The IPA can be used for many different purposes. For instance, it can be used as a way to show pronunciation in a dictionary, to record a language in linguistic fieldwork, to form the basis of a writing system for a language, or to annotate acoustic and other displays in the analysis of speech. -

Whole Language Instruction Vs. Phonics Instruction: Effect on Reading Fluency and Spelling Accuracy of First Grade Students

Whole Language Instruction vs. Phonics Instruction: Effect on Reading Fluency and Spelling Accuracy of First Grade Students Krissy Maddox Jay Feng Presentation at Georgia Educational Research Association Annual Conference, October 18, 2013. Savannah, Georgia 1 Abstract The purpose of this study is to investigate the efficacy of whole language instruction versus phonics instruction for improving reading fluency and spelling accuracy. The participants were the first grade students in the researcher’s general education classroom of a non-Title I school. Stratified sampling was used to randomly divide twenty-two participants into two instructional groups. One group was instructed using whole language principles, where the children only read words in the context of a story, without any phonics instruction. The other group was instructed using explicit phonics instruction, without a story or any contextual influence. After four weeks of treatment, results indicate that there were no statistical differences between the two literacy approaches in the effect on students’ reading fluency or spelling accuracy; however, there were notable changes in the post test results that are worth further investigation. In reading fluency, both groups improved, but the phonics group made greater gains. In spelling accuracy, the phonics group showed slight growth, while the whole language scores decreased. Overall, the phonics group demonstrated greater growth in both reading fluency and spelling accuracy. It is recommended that a literacy approach should combine phonics and whole language into one curriculum, but place greater emphasis on phonics development. 2 Introduction Literacy is the fundamental cornerstone of a student’s academic success. Without the skill of reading, children will almost certainly have limited academic, economic, social, and even emotional success in school and in later life (Pikulski, 2002). -

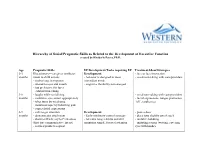

Hierarchy of Social/Pragmatic Skills As Related to the Development of Executive Function Created by Kimberly Peters, Ph.D

Hierarchy of Social/Pragmatic Skills as Related to the Development of Executive Function created by Kimberly Peters, Ph.D. Age Pragmatic Skills EF Development/Tasks requiring EF Treatment Ideas/Strategies 0-3 Illocutionary—caregiver attributes Development: - face to face interaction months intent to child actions - behavior is designed to meet - vocal-turn-taking with care-providers - smiles/coos in response immediate needs - attends to eyes and mouth - cognitive flexibility not emerged - has preference for faces - exhibits turn-taking 3-6 - laughs while socializing - vocal turn-taking with care-providers months - maintains eye contact appropriately - facial expressions: tongue protrusion, - takes turns by vocalizing “oh”, raspberries. - maintains topic by following gaze - copies facial expressions 6-9 - calls to get attention Development: - peek-a-boo months - demonstrates attachment - Early inhibitory control emerges - place toys slightly out of reach - shows self/acts coy to Peek-a-boo - tolerates longer delays and still - imitative babbling (first true communicative intent) maintains simple, focused attention - imitating actions (waving, covering - reaches/points to request eyes with hands). 9-12 - begins directing others Development: - singing/finger plays/nursery rhymes months - participates in verbal routines - Early inhibitory control emerges - routines (so big! where is baby?), - repeats actions that are laughed at - tolerates longer delays and still peek-a-boo, patta-cake, this little piggy - tries to restart play maintain simple, -

Linguistic Scaffolds for Writing Effective Language Objectives

Linguistic Scaffolds for Writing Effective Language Objectives An effectively written language objective: • Stems form the linguistic demands of a standards-based lesson task • Focuses on high-leverage language that will serve students in other contexts • Uses active verbs to name functions/purposes for using language in a specific student task • Specifies target language necessary to complete the task • Emphasizes development of expressive language skills, speaking and writing, without neglecting listening and reading Sample language objectives: Students will articulate main idea and details using target vocabulary: topic, main idea, detail. Students will describe a character’s emotions using precise adjectives. Students will revise a paragraph using correct present tense and conditional verbs. Students will report a group consensus using past tense citation verbs: determined, concluded. Students will use present tense persuasive verbs to defend a position: maintain, contend. Language Objective Frames: Students will (function: active verb phrase) using (language target) . Students will use (language target) to (function: active verb phrase) . Active Verb Bank to Name Functions for Expressive Language Tasks articulate defend express narrate share ask define identify predict state compose describe justify react to summarize compare discuss label read rephrase contrast elaborate list recite revise debate explain name respond write Language objectives are most effectively communicated with verb phrases such as the following: Students will point out similarities between… Students will express agreement… Students will articulate events in sequence… Students will state opinions about…. Sample Noun Phrases Specifying Language Targets academic vocabulary complete sentences subject verb agreement precise adjectives complex sentences personal pronouns citation verbs clarifying questions past-tense verbs noun phrases prepositional phrases gerunds (verb + ing) 2011 Kate Kinsella, Ed.D. -

Linguistics As a Resouvce in Language Planning. 16P

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 095 698 FL 005 720 AUTHOR Garvin, Paul L. TITLE' Linguistics as a Resouvce in Language Planning. PUB DATE Jun 73 NOTE 16p.; PaFPr presented at the Symposium on Sociolinguistics and Language Planning (Mexico City, Mexico, June-July, 1973) EPRS PPICE MF-$0.75 HC-$1.50 PLUS POSTAGE DESCRIPTORS *Applied Linguistics; Language Development; *Language Planning; Language Role; Language Standardization; Linguistics; Linguistic Theory; Official Languages; Social Planning; *Sociolinguistics ABSTPACT Language planning involves decisions of two basic types: those pertaining to language choice and those pertaining to language development. linguistic theory is needed to evaluate the structural suitability of candidate languages, since both official and national languages mast have a high level of standardizaticn as a cultural necessity. On the other hand, only a braodly conceived and functionally oriented linguistics can serve as a basis for choosiag one language rather than another. The role of linguistics in the area of language development differs somewhat depending on whether development is geared in a technological and scientific or a literary, artistic direction. In the first case, emphasis is on the development of terminologies, and in the second case, on that of grammatical devices and styles. Linguistics can provide realistic and practical arguments in favor of language development, and a detailed, technical understanding of such development, as well as methodological skills. Linguists can and must function as consultants to those who actually make decisions about language planning. For too long linguists have pursued only those aims generated within their own field. They must now broaden their scope to achieve the kind of understanding of language that is necessary for a productive approach to concrete language problems. -

New Paradigm for the Study of Simultaneous V. Sequential Bilingualism

New Paradigm for the Study of Simultaneous v. Sequential Bilingualism Suzanne Flynn1, Claire Foley1 and Inna Vinnitskaya2 1MIT and 2University of Ottawa 1. Introduction Mastering multiple languages is a commonplace linguistic achievement for most of the world’s population. Chomsky (in Mukherji et al. 2000) notes that “In most of human history and in most parts of the world today, children grow up speaking a variety of languages…” Clearly, multilingualism “is just a natural state of the human mind.” Notably, most of this language learning occurs in untutored, naturalistic settings and throughout the lifespan of an individual. The false sense of language homogeneity and monolingualism that is often heralded in the United States, at least in certain regional sections, is clearly a historical artifact. As Chomsky notes: Even in the United States the idea that people speak one language is not true. Everyone grows up hearing many different languages. Sometimes they are called “dialects or stylistic variants or whatever” but they are really different languages. It is just that they are so close to each other that we don’t bother calling them different languages (Chomsky, in Mukherji et al., 2000:19 ) A conclusion is that every individual, by virtue of living within a community, is bilingual1 in some sense. Further, this means that in the same sense there is essentially universal multilingualism in the world. Despite the centrality of multilingualism to the human experience, however, questions persist concerning how learners construct new language -

Thieves' Cant: a Primer for the Language of Larceny

Thieves Cant: A primer for the language of larceny by Aurelio Locsin INTRODUCTION As with nouns, modifiers may be doubled. This indicates an This work is made possible through the efforts of several increase in quality or intensity. For example, sio kal means “big linguists, many of whom have lost their lives in their attempts to box”; siosio kal means “very big box”; and siosio kalkal means learn as much as they could about Thieves’ Cant. Although this “very big boxes.” primer and the accompanying translation dictionary are admit- tedly incomplete, this is believed to be the most extensive NUMBERS compilation to date of the language. Many numbers, including 0 through 10 and some higher numbers, are included in the accompanying dictionary as se- PRONUNCIATION AND WRITING parate entries. To create other numbers, simply “add” two or Vowel sounds in Cant are sounded the same way as in these more “number words” together. For example, “seventeen” is English words: “a” as in bad; “e” as in bed; “i” as in bid; “o” as in imboula, or “10” (imbo) plus “7” (ula); and “seventy” is ulaimbo, lone; “u” as in suit; and “y” as in sly. Optionally, for easier which translates as “seven tens.” pronunciation by those accustomed to English, “i” can be Ordinal numbers, to show the order of an item in a succes- sounded like the “e” in see when the “i” appears in the middle or sion of items, are formed by adding the suffix “nk” to the at the end of a word, and the “y” sound is shortened to sound cardinal number (or “ink,” if the number ends in a consonant). -

Why Major in Linguistics (And What Does a Linguist Do)? by Monica Macaulay and Kristen Syrett

1 Why Major in Linguistics (and what does a linguist do)? by Monica Macaulay and Kristen Syrett What is linguistics? Speakers of all languages know a lot about their languages, usually without knowing that they know If you are considering becoming a linguistics it. For example, as a speaker of English, you major, you probably know something about the possess knowledge about English word order. field of linguistics already. However, you may find Perhaps without even knowing it, you understand it hard to answer people who ask you, "What that Sarah admires the teacher is grammatical, exactly is linguistics, and what does a linguist do?" while Admires Sarah teacher the is not, and also They might assume that it means you speak a lot of that The teacher admires Sarah means something languages. And they may be right: you may, in entirely different. You know that when you ask a fact, be a polyglot! But while many linguists do yes-no question, you may reverse the order of speak multiple languages—or at least know a fair words at the beginning of the sentence and that the bit about multiple languages—the study of pitch of your voice goes up at the end of the linguistics means much more than this. sentence (for example, in Are you going?). Linguistics is the scientific study of language, and However, if you speak French, you might add est- many topics are studied under this umbrella. At the ce que at the beginning, and if you know American heart of linguistics is the search for the unconscious knowledge that humans have about language and how it is that children acquire it, an understanding of the structure of language in general and of particular languages, knowledge about how languages vary, and how language influences the way in which we interact with each other and think about the world. -

Defending Whole Language: the Limits of Phonics Instruction and the Efficacy of Whole Language Instruction

Defending Whole Language: The Limits of Phonics Instruction and the Efficacy of Whole Language Instruction Stephen Krashen Reading Improvement 39 (1): 32-42, 2002 The Reading Wars show no signs of stopping. There appear to be two factions: Those who support the Skill-Building hypothesis and those who support the Comprehension Hypothesis. The former claim that literacy is developed from the bottom up; the child learns to read by first learning to read outloud, by learning sound-spelling correspondences. This is done through explicit instruction, practice, and correction. This knowledge is first applied to words. Ultimately, the child uses this ability to read larger texts, as the knowledge of sound-spelling correspondences becomes automatic. According to this view, real reading of interesting texts is helpful only to the extent that it helps children "practice their skills." The Comprehension Hypothesis claims that we learn to read by understanding messages on the page; we "learn to read by reading" (Goodman, 1982; Smith, 1994). Reading pedagogy, according to the Comprehension Hypothesis, focuses on providing students with interesting, comprehensible texts, and the job of the teacher is to help children read these texts, that is, help make them comprehensible. The direct teaching of "skills" is helpful only when it makes texts more comprehensible. The Comprehension Hypothesis also claims that reading is the source of much of our vocabulary knowledge, writing style, advanced grammatical competence, and spelling. It is also the source of most of our knowledge of phonics. Whole Language The term "whole language" does not refer only to providing interesting comprehensible texts and helping children understand less comprehensible texts. -

Pragmatic Language

PRAGMATIC LANGUAGE Pragmatics refers to the social language skills we use in our daily interactions with others. Pragmatic language includes the appropriate content of our words, how we say them, and our use of body language. Pragmatic skills are vital for communicating our personal thoughts, ideas and feelings. Children, adolescents and adults with poor pragmatic skills often misinterpret another person’s communicative intent and have difficulty responding appropriately either verbally or non-verbally. Examples of pragmatic language skills: Verbal communication: • Asking for, giving and responding to information • Turn taking • Eye contact • Introducing and maintaining topics • Making relevant and appropriate contributions to a topic • Asking questions • Avoiding repetitious/redundant information • Asking for clarification • Adjusting language based on situation or communication partners • Using language of a given peer group • Using humor • Using appropriate strategies for gaining attention and interrupting • Asking for help or offering help appropriately • Offering/responding to expressions of affection appropriately Non-Verbal Communication: • Facial expression • Body language • Intonation of voice • Body distance and personal space Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder may have particular difficulty with many of these skills due to their deficits with social interactions. Children with language disorders may also have difficulty exhibiting appropriate pragmatic skills. Use of visual supports such as pictures/symbols is one strategy used in supporting students who have difficulties with social skills. These skills often need to be explicitly taught via social stories. Providing good role models and role-playing situations may assist children with poor pragmatic skills and enable them to practice appropriate behaviors. . -

Philosophy of Language in the Twentieth Century Jason Stanley Rutgers University

Philosophy of Language in the Twentieth Century Jason Stanley Rutgers University In the Twentieth Century, Logic and Philosophy of Language are two of the few areas of philosophy in which philosophers made indisputable progress. For example, even now many of the foremost living ethicists present their theories as somewhat more explicit versions of the ideas of Kant, Mill, or Aristotle. In contrast, it would be patently absurd for a contemporary philosopher of language or logician to think of herself as working in the shadow of any figure who died before the Twentieth Century began. Advances in these disciplines make even the most unaccomplished of its practitioners vastly more sophisticated than Kant. There were previous periods in which the problems of language and logic were studied extensively (e.g. the medieval period). But from the perspective of the progress made in the last 120 years, previous work is at most a source of interesting data or occasional insight. All systematic theorizing about content that meets contemporary standards of rigor has been done subsequently. The advances Philosophy of Language has made in the Twentieth Century are of course the result of the remarkable progress made in logic. Few other philosophical disciplines gained as much from the developments in logic as the Philosophy of Language. In the course of presenting the first formal system in the Begriffsscrift , Gottlob Frege developed a formal language. Subsequently, logicians provided rigorous semantics for formal languages, in order to define truth in a model, and thereby characterize logical consequence. Such rigor was required in order to enable logicians to carry out semantic proofs about formal systems in a formal system, thereby providing semantics with the same benefits as increased formalization had provided for other branches of mathematics.