American Indians in the House Beautiful, 1896-1906

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Entertainment & Syndication Fitch Group Hearst Health Hearst Television Magazines Newspapers Ventures Real Estate & O

hearst properties WPBF-TV, West Palm Beach, FL SPAIN Friendswood Journal (TX) WYFF-TV, Greenville/Spartanburg, SC Hardin County News (TX) entertainment Hearst España, S.L. KOCO-TV, Oklahoma City, OK Herald Review (MI) & syndication WVTM-TV, Birmingham, AL Humble Observer (TX) WGAL-TV, Lancaster/Harrisburg, PA SWITZERLAND Jasper Newsboy (TX) CABLE TELEVISION NETWORKS & SERVICES KOAT-TV, Albuquerque, NM Hearst Digital SA Kingwood Observer (TX) WXII-TV, Greensboro/High Point/ La Voz de Houston (TX) A+E Networks Winston-Salem, NC TAIWAN Lake Houston Observer (TX) (including A&E, HISTORY, Lifetime, LMN WCWG-TV, Greensboro/High Point/ Local First (NY) & FYI—50% owned by Hearst) Winston-Salem, NC Hearst Magazines Taiwan Local Values (NY) Canal Cosmopolitan Iberia, S.L. WLKY-TV, Louisville, KY Magnolia Potpourri (TX) Cosmopolitan Television WDSU-TV, New Orleans, LA UNITED KINGDOM Memorial Examiner (TX) Canada Company KCCI-TV, Des Moines, IA Handbag.com Limited Milford-Orange Bulletin (CT) (46% owned by Hearst) KETV, Omaha, NE Muleshoe Journal (TX) ESPN, Inc. Hearst UK Limited WMTW-TV, Portland/Auburn, ME The National Magazine Company Limited New Canaan Advertiser (CT) (20% owned by Hearst) WPXT-TV, Portland/Auburn, ME New Canaan News (CT) VICE Media WJCL-TV, Savannah, GA News Advocate (TX) HEARST MAGAZINES UK (A+E Networks is a 17.8% investor in VICE) WAPT-TV, Jackson, MS Northeast Herald (TX) VICELAND WPTZ-TV, Burlington, VT/Plattsburgh, NY Best Pasadena Citizen (TX) (A+E Networks is a 50.1% investor in VICELAND) WNNE-TV, Burlington, VT/Plattsburgh, -

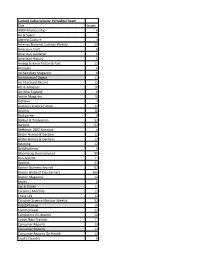

Current Subscriptions: Periodical Room Title Issues AARP

Current Subscriptions: Periodical Room Title Issues AARP Membership 6 Air & Space 7 Altered Couture 4 America National Catholic Weekly 29 American Craft 6 American Gardener 6 American History 6 Analog Science Fiction & Fact 12 Antiques 6 Archaeology Magazine 6 Architectural Digest 12 Architectural Record 12 Art & Antiques 10 Art New England 6 Artists Magazine 10 ArtNews 4 Asimov's Science Fiction 12 Atlantic 10 Backpacker 9 Banker & Tradesman 52 Barrons 52 Beekman 1802 Almanac 4 Better Homes & Gardens 12 Better Homes & Gardens 12 Bicycling 12 BirdWatching 6 Bloomberg Businessweek 50 Bon Appetit 11 Booklist 22 Boston Business Journal 52 Boston Globe (7 Day Carrier) 365 Boston Magazine 12 Brides 6 Car & Driver 12 Ceramics Monthly 12 Chess Life 12 Christian Science Monitor Weekly 52 Coastal Living 10 Commonweal 22 Computers In Libraries 10 Conde Nast Traveler 11 Consumer Reports 13 Consumer Reports 13 Consumer Reports On Health 12 Cook's Country 6 Cook's Illustrated 6 Cooking Light 12 Cosmopolitan 12 Country Living 10 Discover 10 Domino 4 Down East Magazine 12 Dwell Magazine 6 Easy English News 10 Eating Well 6 Economist 51 Elle 12 Entertainment Weekly 46 Entrepreneur 10 Esquire 10 Family Handyman 8 Fast Company 10 Financial Times 312 Fine Cooking 6 Fine Gardening 6 Fine Homebuilding 8 Fine Woodworking 7 Food & Wine 12 Food Network Magazine 10 Forbes 18 Foreign Affairs 6 Fortune 14 France-Amerique 11 Glamour 16 Good Housekeeping 12 GQ - Gentlemens Quarterly 12 Guardian Weekly 52 Harper's Bazaar 10 Harper's Magazine 12 Harvard Health Letter 12 Harvard Women's Health Watch 12 Health 10 HGTV 10 History Today 12 House Beautiful 10 Inc. -

United Kingdom Distribution Points

United Kingdom Distribution to national, regional and trade media, including national and regional newspapers, radio and television stations, through proprietary and news agency network of The Press Association (PA). In addition, the circuit features the following complimentary added-value services: . Posting to online services and portals with a complimentary ReleaseWatch report. Coverage on PR Newswire for Journalists, PR Newswire's media-only website and custom push email service reaching over 100,000 registered journalists from 140 countries and in 17 different languages. Distribution of listed company news to financial professionals around the world via Thomson Reuters, Bloomberg and proprietary networks. Releases are translated and distributed in English via PA. 3,298 Points Country Media Point Media Type United Adones Blogger Kingdom United Airlines Angel Blogger Kingdom United Alien Prequel News Blog Blogger Kingdom United Beauty & Fashion World Blogger Kingdom United BellaBacchante Blogger Kingdom United Blog Me Beautiful Blogger Kingdom United BrandFixion Blogger Kingdom United Car Design News Blogger Kingdom United Corp Websites Blogger Kingdom United Create MILK Blogger Kingdom United Diamond Lounge Blogger Kingdom United Drink Brands.com Blogger Kingdom United English News Blogger Kingdom United ExchangeWire.com Blogger Kingdom United Finacial Times Blogger Kingdom United gabrielleteare.com/blog Blogger Kingdom United girlsngadgets.com Blogger Kingdom United Gizable Blogger Kingdom United http://clashcityrocker.blogg.no Blogger -

Strawberry Festivals a Wilk Ropaleag Caasky Find Out.” of Rur-Mil Multialamont Rayon Crapa, If Comas Camels Suit Me Quarter of a Century Ago

TUESDAY, JUNE *0, W M Avarsga Daily Nat Preoa Run m l Wl ■ ^ A, ^ A A 1 ^ m a d — ^ J1 B A A- .a A- 1 TIm ■awaa jHanrlfieBtfr lEnpning For the Month of May, I960 Today cleody with shswaf aad dally nawapapar baatdaa aattliiff up Toung people of the North Thomaa J. taw la o( Middla Uialr campialgiia and eourta. Prao- ■eattered thoadenitonaai taolght Tumpika, caat, who accompanlad ^,9 2 4 2 /ltlaU i'JjF ju i'F r i l u u F u i U ^ J l r r a i l l Methodist church will serve a Receives Degree Six from Here tical Idaala ara Uia baala o f all olMdy, some ehowetei teosorrsw, About Town *nd itrawberry shortcake Dr. David H. Nelson and William Member of the Audit E. Hill, who are now in Loa An Boya’ State oparationa roundid scattered ehowem. supper tomorrow evening from out with auparvlaad athlatic, mual- Bnreaa of Clreulations Manchester^A CUy of Vittage Charm ■ • n m tlo a a wOl doa* thla cvt- 5:30 to T:30. ____ geles attending the national con At Boys State vention of the Ancient Arabic Or cal and entertainment programa. lo r tba fourth onnual deo* DisUngulahed Connactirat ciU- M t rtT*T ot tho Bolton Oongro- Members of the Women’a Polish der, Nobles of the Mystic Shrine, reports a fine trip to the Pacific sans will visit Boya* State dally MANCHESTER, CONN„ WEDNESDAY, JUNE 21,1950 (TWENTY PAGES) n t t o S chnioh. Ttiurodoy e v ^ Alliance, Group 246, ere requested Youth Government Pro to give Inapirlng talks to the boys (Claaslfled Aiverttalng oa Page IS) PRICE FOUR CBNIB oiz to eight o’clock. -

HEARST PROPERTIES HUNGARY HEARST MAGAZINES UK Hearst Central Kft

HEARST PROPERTIES HUNGARY HEARST MAGAZINES UK Hearst Central Kft. (50% owned by Hearst) All About Soap ITALY Best Cosmopolitan NEWSPAPERS MAGAZINES Hearst Magazines Italia S.p.A. Country Living Albany Times Union (NY) H.M.C. Italia S.r.l. (49% owned by Hearst) Car and Driver ELLE Beaumont Enterprise (TX) Cosmopolitan JAPAN ELLE Decoration Connecticut Post (CT) Country Living Hearst Fujingaho Co., Ltd. Esquire Edwardsville Intelligencer (IL) Dr. Oz THE GOOD LIFE Greenwich Time (CT) KOREA Good Housekeeping ELLE Houston Chronicle (TX) Hearst JoongAng Y.H. (49.9% owned by Hearst) Harper’s BAZAAR ELLE DECOR House Beautiful Huron Daily Tribune (MI) MEXICO Laredo Morning Times (TX) Esquire Inside Soap Hearst Expansion S. de R.L. de C.V. Midland Daily News (MI) Food Network Magazine Men’s Health (50.1% owned by Hearst UK) (51% owned by Hearst) Midland Reporter-Telegram (TX) Good Housekeeping Prima Plainview Daily Herald (TX) Harper’s BAZAAR NETHERLANDS Real People San Antonio Express-News (TX) HGTV Magazine Hearst Magazines Netherlands B.V. Red San Francisco Chronicle (CA) House Beautiful Reveal The Advocate, Stamford (CT) NIGERIA Marie Claire Runner’s World (50.1% owned by Hearst UK) The News-Times, Danbury (CT) HMI Africa, LLC O, The Oprah Magazine Town & Country WEBSITES Popular Mechanics NORWAY Triathlete’s World Seattlepi.com Redbook HMI Digital, LLC (50.1% owned by Hearst UK) Road & Track POLAND Women’s Health WEEKLY NEWSPAPERS Seventeen Advertiser North (NY) Hearst-Marquard Publishing Sp.z.o.o. (50.1% owned by Hearst UK) Town & Country Advertiser South (NY) (50% owned by Hearst) VERANDA MAGAZINE DISTRIBUTION Ballston Spa/Malta Pennysaver (NY) Woman’s Day RUSSIA Condé Nast and National Magazine Canyon News (TX) OOO “Fashion Press” (50% owned by Hearst) Distributors Ltd. -

Digital Magazines for Ipads + Android

Digital Magazines For iPads + Android RBdigital App allows you to read complete, full-color magazines on your tablet, computer or smartphone. Sample Titles Architectural Digest Billboard Bon Appetit Car and Driver Chicago Magazine Cook’s Illustrated Discover Cosmopolitan Elle The Economist Entrepreneur ESPN The Magazine Harper’s Bazaar House Beautiful Kiplinger’s Personal Finance Men’s Health National Enquirer National Geographic Newsweek New York Review of Books Page 1 of 6 Note – this guide uses an iPad for its images – you may see a slightly different layout if you are using a different device. For first time users, you must start by using an internet browser such as Internet Explorer, Chrome, Firefox, etc. 1. Visit the library’s RBdigital website: www.rbdigital.com/winnnorthil (that’s three Ns) ↑ 2. Here you will see our available magazines. If this is your first time using the service, click the Create New Account link in the upper right: 3. You will be asked for your library card number – enter it without spaces: Page 2 of 6 4. On the following screen, enter your information, then hit Create Account: You will know that you have successfully created the account when you see your name in the upper right of the screen: 5. You are now ready to select your first magazine. Search in the upper left, or choose a genre to browse in the upper right – or simply scroll down to browse the whole collection alphabetically. Page 3 of 6 6. To check out a magazine, click/tap the icon just beneath its cover, to the right: To read your checked out magazines, you can read from your internet browser or on your smartphone or tablet by downloading the RBdigital app. -

Women Breaking Boundaries

WOMEN BREAKING BOUNDARIES Permanent Collection Artwork List A comprehensive list of artworks by artists who identify as female, as well as works that portray strong female subjects, on view throughout the Cincinnati Art Museum’s permanent collection galleries from October 2019 to May 2020. The list is organized by gallery number and artworks in the gallery are identified by theWomen Breaking Boundaries logo. FIRST FLOOR Caroline Wilson (1810–1890), United Pitcher, 1881, Laura Anne Fry (1857– States, The Reverend Lyman A. Beecher, 1943), Cincinnati Pottery Club (estab. Alice Bimel Courtyard designed circa 1842, carved 1860 1879, closed 1890), United States, Harriet Whitney Frishmuth (1880–1980), marble, Gift of the Artist, 1885.12 earthenware, Dull Finish glaze line, United States, The Vine, 1923, bronze, Gift of Women’s Art Museum Centennial Gift of Dwight J. Thomson, Gallery 108 Association, 1881.48 1980.258 Lilly Martin Spencer (1822–1902), United States, Patty Cake, circa 1855, Pocket Vase, 1881, The Rookwood Harriet Whitney Frishmuth (1880–1980), oil on canvas, Museum Purchase: Pottery Company (estab. 1880), United States, The Star, 1923, bronze Bequest of Mr. and Mrs. Walter J. decorator, Maria Longworth Nichols Centennial Gift of Dwight J. Thomson, Wichgar, 1999.214 Storer (1849–1932), decorator, United 1980.259 States, earthenware, Limoges glaze Gallery 110 line, Gift of Women’s Art Museum Gallery 101 Elizabeth Boott Duveneck (1846–1888), Association, 1881.36 Turkey (Mersin), Cypriot Head of a United States, Woman and Children, Umbrella Stand, 1880, Mary Louise Priestess or Goddess, 5th–4th century 1878, oil on canvas, Gift of Frank McLaughlin (1847–1939), Frederick BCE, limestone with traces of paint, Duveneck, 1915.254 Museum Purchase, 2001.321 Dallas Hamilton Road Pottery (estab. -

What Drove Big Gains During a Traditionally Slow Month 2016 Was

January 16, 2017 | Vol. 70 No. 2 Read more at: minonline.com Top Story: What Drove Big Gains During a Traditionally Slow Month Trump’s November surprise, access and Amish cookies were in the mix. Traditionally, November is a struggle for digital content of all kinds as mindshare shifts to e-commerce for the month. This year, however, many of the titles tracked by the Magazine Media 360º Brand Audience Report benefitted from citizens shop- ping for any and all news around the historic election surprise. A range of publishers outside the usual political fold enjoyed some of the most extreme traffic spikes from their takes on pre- and post-Election Day news. But I was also struck by how many magazine digital success stories in November underscored the enduring power of magazine brands themselves. Maga- zines continue to command exclusivity and access that digital natives do not. New York magazine (+9.3% desktop, +114.8% mobile, +58.5% video) broke its personal best unique visitor record, led by its Daily Intelligence brand. Post-mortem pieces drew the most views. It was a similar story at Bloomberg Businessweek (-13.9% desktop, +88.9% mobile, +20.3% video) where its political content led on mobile and especially video. Businessweek is distributing digital and TV clips across both traditional digital and OTT apps, but the brand also launched a new Technology vertical in November. Likewise for Esquire (-5.4% desktop, +80.4% mobile, +177.4% video), which flexed its star columnist muscle with com- mentary from Charles Pierce, enjoyed a record-breaking month. -

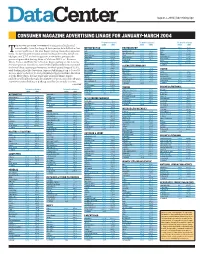

Ad Linage for Jan.-March 2004

Linage 1Q 07-26-04.qxd 7/29/04 3:03 PM Page 1 DataCenter August 2, 2004 | Advertising Age CONSUMER MAGAZINE ADVERTISING LINAGE FOR JANUARY-MARCH 2004 1st-quarter ad pages 1st-quarter ad pages 1st-quarter ad pages he second quarter's numbers for magazines brightened 2004 2003 2004 2003 2004 2003 considerably from the sluggish first quarter detailed below, but METROPOLITAN PHOTOGRAPHY Teen Vogue C. 132.66 80.49 Victoria C. 0.00 70.43 some trendlines of the year began making themselves apparent Boston 269.20 279.50 American Photo (6X) C. 109.02 96.65 T Vogue C. 639.48 715.27 Chicago 263.26 233.15 Outdoor Photographer (10X) 160.59 160.59 early. A near-flat performance at national business titles, which saw W Magazine C. 485.44 438.15 Chicago’s North Shore 126.63 122.37 PC Photo 104.87 120.57 Weight Watchers (6X) C. 148.13 126.18 ad pages sink 2.7% in the first quarter, nonetheless presages the Columbus Monthly 190.65 208.08 Popular Photography C. 380.00 390.76 Woman’s Day (15X) C. 347.02 357.89 Connecticut 136.26 176.50 TOTAL GROUP 754.48 768.57 positive figures that the big-three of McGraw-Hill Cos.' Business YM (11X) C. 108.69 190.16 Diablo 259.11 241.56 % CHANGE -1.83 Week, Forbes, and Time Inc.'s Fortune began putting on the board as TOTAL GROUP 11883.59 12059.13 Indianapolis Monthly 397.00 345.00 % CHANGE -1.46 the year went on. -

2018 Magazine Holdings Main

Magazine Holdings TITLE DATES FOR 16 CURRENT ACORN CURRENT ADVERTISING AGE 5 YEARS AFFIRMATIVE ACTION REGISTER 4 ISSUES AIR FORCE DISCONTINUED ALA WASHINGTON NEWSLETTER 1993-97 AMERICA 1/70- AMERICAN ARTIST 1/56- AMERICAN CRAFT 8/79- AMERICAN DEMOGRAPHICS 1/88- AMERICAN GIRL CURRENT AMERICAN HERITAGE 12/54- 6/72-4/79;4/82-88;3/93- AMERICAN HISTORY 4/94 AMERICAN HISTORY ILLUSTRATED 6/94- AMERICAN LIBRARIES AMERICAN QUILTER 1/71- AMERICAN RIFLEMAN 4 ISSUES AMERICAN SCHOLAR 5 YEARS AMERICANA SPR.'69- AMERICAS 3/73-2/93 ANTIQUE TRADER WEEKLY 12/63- ANTIQUES 4 ISSUES ANTIQUES AND COLLECTING 1/66- ARCHAEOLOGY MAGAZINE 5 YEARS ARCHITECTURAL DIGEST 1 YEAR ARCHITECTURAL RECORD 1/76- ARIZONA HIGHWAYS 1/67- ART IN AMERICA 1 YEAR ATLANTA JOURNAL - CONSTITUTION 1/68- ATLANTIC MONTHLY 2 SUNDAYS Ask at Reference Desk for back issues Magazine Holdings AUDUBON 1/25- AVIATION WEEK & SPACE TECHNOLOGY 1/66- BARRON'S 11/74- BESTS REVIEW LIFE-HEALTH BESTS REVIEW PROPERTY-CASUALTY 5 YEARS BETTER HOMES & GARDENS 2 YEARS BICYCLING 2 YEARS BOATING 1/56- BON APPETIT 5 YEARS BOODLE BOOKLIST BOSTON GLOBE BOTTOM LINE 5 YEARS BOYS' LIFE 1 YEAR BRITISH HERITAGE CURRENT BROADCASTING/CABLE 1/72- BULLETIN OF CENTER FOR CHILDRENS' BOOKS 4 ISSUES BUSINESS AMERICA 5 YEARS BUSINESS BAROMETER OF CENTRAL FLORIDA CURRENT BUSINESS HORIZONS 1 YEAR BUSINESS WEEK 5 YEARS BYTE YS CAR & DRIVER INCOMPLETE CATALOGING & CLASSIFICATION QUARTERLY 2/79-4/88 CATS 5 YEARS CHANGING TIMES 4/39- CHARTCRAFT 9/81-7/98 CHICAGO TRIBUNE 4/79- CHOICE FALL'83- CHRISTIAN CENTURY Ask at Reference Desk -

Title Publisher Subject Simple & Delicious Trusted Media Brands

Title Publisher Subject Simple & Delicious Trusted Media Brands, Inc. Cooking & Food Country Woman Trusted Media Brands, Inc. Home & Garden, Women's Interest Car and Driver Hearst Magazines Automotive Cosmopolitan Hearst Magazines Adult, Fashion, Lifestyle, Women's Interest ELLE Hearst Magazines Fashion, Lifestyle, Women's Interest Elle Decor Hearst Magazines Lifestyle, Women's Interest Esquire Hearst Magazines Lifestyle, Men's Interest Food Network Magazine Hearst Magazines Cooking & Food, Health Harper's BAZAAR Hearst Magazines Fashion, Lifestyle, Women's Interest HGTV Magazine Hearst Magazines Entertainment, Home & Garden, TV Guide House Beautiful Hearst Magazines Home & Garden, Lifestyle Marie Claire Hearst Magazines Fashion, Lifestyle, Women's Interest Popular Mechanics Hearst Magazines Automotive, Science REDBOOK Hearst Magazines Lifestyle, Women's Interest Seventeen Hearst Magazines Fashion, Young Adults O, The Oprah Magazine Hearst Magazines Fashion, Lifestyle, Women's Interest Town & Country Hearst Magazines Fashion, Lifestyle, Women's Interest Woman's Day Hearst Magazines Lifestyle, Women's Interest Fast Company Mansueto Ventures, LLC Business & Finance Inc. Mansueto Ventures, LLC Business & Finance Newsweek Newsweek Business & Finance, News, Politics Muscle & Fitness American Media, Inc. Health, Men's Interest OK! American Media, Inc. Celebrity, Entertainment, News Soap Opera Digest American Media, Inc. Celebrity, Entertainment Star American Media, Inc. Celebrity, Entertainment, News New York Magazine New York Magazine Lifestyle, News, Politics Saveur Bonnier Cooking & Food Guideposts Guideposts Health, Lifestyle The Atlantic Atlantic Media Journals, News, Politics ESPN The Magazine ESPN Magazine Sports Popular Science Bonnier Science, Technology Field & Stream Bonnier Lifestyle, Men's Interest, Sports Motor Trend TEN: The Enthusiast Network Automotive, Men's Interest Taste of Home Trusted Media Brands, Inc. -

Lawrence B. Romaine Trade Catalog Collection

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/tf4w1007j8 No online items Lawrence B. Romaine Trade Catalog Collection Processing Information: Preliminary arrangement and description by Rosanne Barker, Viviana Marsano, and Christopher Husted; latest revision D. Tambo, D. Muralles. Machine-readable finding aid created by Xiuzhi Zhou, latest revision A. Demeter. Department of Special Collections Davidson Library University of California, Santa Barbara Santa Barbara, CA 93106 Phone: (805) 893-3062 Fax: (805) 893-5749 Email: [email protected] URL: http://www.library.ucsb.edu/special-collections/ © 2000-2013 The Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. Lawrence B. Romaine Trade Mss 107 1 Catalog Collection Preliminary Guide to the Lawrence B. Romaine Trade Catalog Collection, ca. 1850-1968 Collection number: Mss 107 Department of Special Collections Davidson Library University of California, Santa Barbara Contact Information: Department of Special Collections Davidson Library University of California, Santa Barbara Santa Barbara, CA 93106 Phone: (805) 893-3062 Fax: (805) 893-5749 Email: [email protected] URL: http://www.library.ucsb.edu/special-collections/ Processing Information: Preliminary arrangement and description by Rosanne Barker, Viviana Marsano, and Christopher Husted; latest revision by D. Tambo and D. Muralles. Date Completed: Dec. 30, 1999 Latest revision: June 11, 2012 Encoded by: Xiuzhi Zhou, A. Demeter © 2000, 2012 The Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. Descriptive Summary Title: Lawrence B. Romaine Trade Catalog Collection Dates: ca. 1850-1968 Collection number: Mss 107 Creator: Romaine, Lawrence B., 1900- Collection Size: ca. 525.4 linear feet (about 1171 boxes and 1 map drawer) Repository: University of California, Santa Barbara.