Top Left-Hand Corner

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Case Study on the Two Turkısh Translatıons of Paul Auster's Cıty Of

Hacettepe University Graduate School of Social Sciences Department of Translation and Interpretation A CASE STUDY ON THE TWO TURKISH TRANSLATIONS OF PAUL AUSTER’S CITY OF GLASS İpek HÜYÜKLÜ Master’s Thesis Ankara, 2015 A CASE STUDY ON THE TWO TURKISH TRANSLATIONS OF PAUL AUSTER’S CITY OF GLASS İpek HÜYÜKLÜ Hacettepe University Graduate School of Social Sciences Department of Translation and Interpretation Master’s Thesis Ankara, 2015 iii ÖZET HÜYÜKLÜ, İpek. Paul Auster’ın Cam Kent adlı Eserinin İki Çevirisi üzerine bir Çalışma. Yüksek Lisans Tezi, Ankara, 2015. Bu çalışmanın amacı, Paul Auster’ın Cam Kent romanının iki farklı çevirisinde çevirmene zorluk yaratacak öğelerin çevirmenler tarafından nasıl çevrildiğini Venuti’nin yerlileştirme ve yabancılaştırma kavramları ışığı altında analiz ederek çevirmenlerin uyguladıkları stratejileri tespit etmektir. Bunun yanı sıra Venuti’nin çevirmenin görünürlüğü ve görünmezliği yaklaşımları temel alınarak hangi çevirmenin daha görünür ya da görünmez olduğunu ortaya koymak amaçlanmıştır. Bu amaç doğrultusunda, çevirmenler için zorluk yaratan öğelerin sıklıkla kullanıldığı ve postmodern biçemiyle bilinen Paul Auster’a ait Cam Kent adlı eserin Yusuf Eradam (1993) ve İlknur Özdemir (2004) tarafından Türkçe’ye yapılan iki farklı çevirisi analiz edilmiştir. Bu eserin çevirisini zorlaştıran faktörler; özel isimler, kelime oyunları, bireydil, dilbilgisel normlar, tipografi, gönderme ve yabancı sözcükler olmak üzere yedi başlık altında toplanmış olup Cam Kent romanının iki farklı çevirisinde tercih edilen çeviri stratejileri karşılaştırılmıştır. Bu karşılaştırma, Venuti’nin çevirmenin görünmezliği yaklaşımı temel alınarak hangi çevirmenin daha görünür ya da görünmez olduğunu incelemek üzere yapılmıştır. İki çevirinin karşılaştırmalı analizinin ardından, iki çevirmenin de farklı öğeler için yerlileştirme ve yabancılaştırma yaklaşımlarını bir çeviri stratejisi olarak kullandığı sonucuna varılmıştır. -

Pastiche in Paul Auster's the New York Trilogy

qw Advances in Language and Literary Studies ISSN: 2203-4714 Vol. 7 No. 5; October 2016 Australian International Academic Centre, Australia Flourishing Creativity & Literacy Pastiche in Paul Auster’s The New York Trilogy Maedeh Zare’e (Corresponding author) Islamic Azad University, Tehran Central Branch, Iran E-mail: [email protected] Razieh Eslamieh Islamic Azad University, Parand Branch, Iran Doi:10.7575/aiac.alls.v.7n.5p.197 Received: 17/06/2016 URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.7575/aiac.alls.v.7n.5p.197 Accepted: 28/08/2016 Abstract This article is a Jamesonian study of Auster’s The New York Trilogy in which one of Fredric Jameson’s notions of postmodernism, pastiche, has been applied on three stories of the novel. This novel is one of Auster’s outstanding postmodern works to which Jameson’s theories of postmodernism, in particular, pastiche can be applicable. Pastiche has been defined by Fredric Jameson as an imitation of a strange style and contrasted to the concept of postmodern parody. This article indicates that theory of pastiche can be applied on both the form and content of three stories of the above mentioned novel. Keywords: Pastiche, Parody, Depthlessness, Historicity 1. Introduction Paul Benjamin Auster (1947) is one of the most influential American postmodern authors, whose works mostly mix realism, experimentation, sociology, absurdism, existentialism and crime fiction. Pastiche, intertextuality, aesthetic dignity and Auster’s own appearance in his works, such as City of Glass (1985), are also some of the features of his works. The search for identity and self-discovery can be found in his works such as The New York Trilogy (2015)1, Moon Palace (1989), The Music of Chance (1990), The Book of Illusions (2002), and The Brooklyn Follies (2005). -

Download Article (PDF)

Advances in Social Science, Education and Humanities Research, volume 289 5th International Conference on Education, Language, Art and Inter-cultural Communication (ICELAIC 2018) A Review of Paul Auster Studies* Long Shi Qingwei Zhu College of Foreign Language College of Foreign Language Pingdingshan University Pingdingshan University Pingdingshan, China Pingdingshan, China Abstract—Paul Benjamin Auster is a famous contemporary Médaille Grand Vermeil de la Ville de Paris in 2010, American writer. His works have won recognition from all IMPAC Award Longlist for Man in the Dark in 2010, over the world. So far, the Critical Community contributes IMPAC Award long list for Invisible in 2011, IMPAC different criticism to his works from varied perspectives in the Award long list for Sunset Park in 2012, NYC Literary West and China. This paper tries to make a review of Paul Honors for Fiction in 2012. Auster studies, pointing out the achievement which has been made and others need to be made. II. A REVIEW OF PAUL AUSTER‘S LITERARY CREATION Keywords—a review; Paul Auster; studies In 1982, Paul Auster published The Invention of Solitude which reflected a literary mind that was to be reckoned with. I. INTRODUCTION It consists of two sections. Portrait of an Invisible Man, the first part, is mainly about his childhood in which there is an Paul Benjamin Auster (born February 3, 1947) is a absence of fatherly love and care. His memory of his growth talented contemporary American writer with great is full of lack of fatherly attention: ―for the first years of my abundance of voluminous works. -

An Analysis Of" City of Glass" by Paul Auster in Terms of Postmodernism

International Journal of Languages’ Education and Teaching Volume 5, Issue 1, April 2017, p. 478-486 Received Reviewed Published Doi Number 17.01.2017 16.02.2017 24.04.2017 10.18298/ijlet.1659 AN ANALYSIS OF CITY OF GLASS BY PAUL AUSTER FROM A POSTMODERNIST PERSPECTIVE1 Mehmet Cem ODACIOĞLU 2 & Chek Kim LOI3 & Fadime ÇOBAN4 ABSTRACT This study analyzes City of Glass, a postmodernist detective novella (or anti-detective) of the New York Trilogy by Paul Auster in terms of postmodernist elements and techniques such as metafiction, parody, intertextuality, irony. In doing so, some information about Auster’s life and the plot of the work are also offered to the reader to make the analysis more concrete. Last but not least, this study is also thought to be useful for students enrolled in English Language and Literary Departments for them to understand the movement of postmodernism. Key Words: City of Class, postmodernist detective fiction, anti-detective, metafiction, parody, irony, intertextuality, pastiche. 1.Short Biography of Paul Auster Paul Auster is an American-Jewish essayist, novelist, translator, poet, screenwriter and memoirist, who was born in Newark, New Jersey on February 3, 1947. Auster lived in a middle class family and spent some of his childhood in the Newark suburbs of South Orange and Maplewood. However, in 1959, his family moved into a large Tudor house. Auster's uncle, Allen Mandelbaum was a translator and left his books for him to read there when he decided to make a journey to Europe. Auster read all of these books which encouraged him to be interested in writing and in literature. -

Notes On/In Paul Auster's Oracle Night

RSA Journal 14/2003 PIA MASIERO MARCOLIN Notes on/in Paul Auster's Oracle Night Encountering a footnote is like going downstairs to answer the doorbell while making love. Noel Coward I tried to use certain genre conventions to get to another place, another place altogether. Paul Auster Paul Auster's twelfth novel, Oracle Night, is the account of nine days in the life of Sidney Orr told by himself twenty years later. The nine days, starting "on the morning in question — September 18, 1982— " (189) span a (retrospectively) crucial moment in the life of the protagonist/narrator who, while recovering from a near-fatal illness is won back to his job — writing — by a close friend of his, the acclaimed writer John Trause, and by the spellbinding power of a newly acquired blue Portuguese notebook. John Trause (and the new notebook) intrigues him into trying to write a variation of an episode in Hammett's The Maltese Falcon in which a man walks away from his wife and disappears after going through a near-death experience. Almost halfway through the book, the novel progresses on a double track: on the one hand, Sidney Orr's therapeutic walks, his everyday life with his beloved wife Grace and his friend John, and on the other, Nick Bowen's story, his flight to Kansas City, his friendship with a retired taxi-driver, Ed, whom he helps in the heavy 182 Pia Masiero Marcolin job of reorganizing his collection of phone-books in a deserted underground warehouse in which he eventually gets trapped. -

Prophecy and Ontology in Paul Auster's Oracle

The Burden of Proof: Prophecy and Ontology in Paul Auster’s Oracle Night A thesis submitted to the faculty of San Francisco State University In partial fulfillment of The requirements for The degree Master of Arts in English: Literature by Maximilian Rankenburg San Francisco, California May, 2005 The Burden of Proof: Prophecy and Ontology in Paul Auster’s Oracle Night Maximilian Rankenburg San Francisco State University 2005 The Burden of Proof: Prophecy and Ontology in Paul Auster’s Oracle Night is a structuralist reading of Auster's text. By examining the relationship between the structures of the text, and of its protagonist-narrator, I reveal, primarily and specifically, the complex narrative surrounding the question of identity, and formally, the strange border between structuralist and post-structuralist approaches to literature. The essay is in three parts. I begin my investigation with analysis of the concept of an oracle. What does the idea of prophecy do to a normal definition of narrative? I use throughout my essay, more as a heuristic and test-site for my investigation than analogy, the figure from Delphi in Oedipus the King. The second theme, rising from Oedipus's difference with Jocasta – meaning is ab extra; meaning is ab intra – concerns structuralism, or the reassemblage of narrative-parts in an effort at revealing the intelligible function of the whole. The third theme concerns the shortfall of a structuralist view. I do not go so far as to compare my approach to a post-structuralist one; but I make it clear that Sidney Orr's project at memoir, and Oracle Night, indict a form of structuralism. -

The Embodied Author: Problems of Authorship in the Work of Paul Auster

The Embodied Author: Problems of Authorship in the Work of Paul Auster 1 Larissa Schortinghuis 3602249 1 Drawing by M.C. Escher, Drawing Hands (1948). 1 Acknowledgments It took quite a lot of effort to work out the ideas for this thesis and I would like to credit the people who have helped me enormously while I was working on it. First I would like to thank my thesis supervisor, Susanne Knittel, for making this a fun experience and being just as excited about the ideas as I was. Secondly, I would like to thank Marloes Hoogendoorn for the idea of putting Escher’s drawing on my front page and general support. Thirdly, I want to thank Victor Louwerse heartily for putting up with all my ranting and excitement when I figured out all the arguments and for giving me the final criticism when I needed it. Lastly, I would like to thank Japke van Uffelen, Annemarie Sint Jago and Laura Kaai for being my personal cheerleaders when things didn’t go so well. 2 The Embodied Author: Problems of Authorship in the Work of Paul Auster In 1968 Roland Barthes declared that the Author was dead. No longer was there one overruling interpretation that critics could find by going on a scholarly treasure hunt (Barthes, The Death of the Author 1325). The figure called the Author, that was presented as the God of his work and whose intentions were the key to deciphering his text, had now lost his authority. The reader was empowered and the author’s reign was over. -

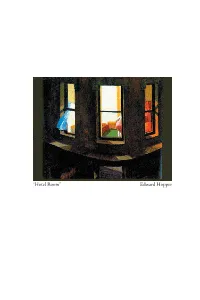

Edward Hopper the Light and the Fogg: Edward Hopper and Paul Auster

“Hotel Room” Edward Hopper The Light and the Fogg: Edward Hopper and Paul Auster James Peacock University of Edinburgh Auster contributed an extract from Moon Palace to the collection “Edward Hopper and the American Imagination,” and it is clear that Hopper’s images of alienated individuals have had a profound resonance for him. This paper employs two main ideas to compare them. First, a pivotal moment in American literature: the hotel room drama watched by Coverdale in Hawthorne’s Blithedale Romance. Secondly, Aby Warburg’s concept of the “pathos formula” in art, which bypasses the problematic issue of influence, choosing instead to posit sets of inherited cultural memories. It therefore allows discussion of the re-emergence of Hawthorne’s puritan tropes of paranoid specularity and transcendence in the work of Hopper and Auster. I was never able to paint what I set out to paint. (Edward Hopper, quoted in O’Doherty 77) Words are transparent for him, great windows that stand between him and the world, and until now they have never impeded his view, have never even seemed to be there. (G 146) Somewhere in New England in the nineteenth century, a man resumes his “post” (Hawthorne 168) at his hotel room window, there to observe the boarding house opposite. Before long, a “knot of characters” enters one of the rooms, appearing before our observer as if projected onto the physi- cal stage, having been “kept so long upon my mental stage, as actors in a drama.” Longing for “a catastrophe,” some moment of high theatre to fill the epistemological void of his own soul, our voyeur gazes with increasing intensity, fabricating scenarios which, he admits, “might have been alto- gether the result of fancy and prejudice in me.” When, in one of the most compelling and influential moments in all American literature, he is spot- ted by the female protagonist and barred from the scene by the dropping of a curtain, his appetite for narrative resolution remains unsated and he is condemned to brood on his isolation once more. -

“Then Catastrophe Strikes:” Reading Disaster in Paul Auster's Novels and Autobiographies « Then Catastrophe Strikes

Université Paris-Est Northwestern University École doctorale CS – Cultures et Sociétés Weinberg College of Arts & Sciences Laboratoire d’accueil : IMAGER Institut des Comparative Literary Studies Mondes Anglophone, Germanique et Roman, EA 3958 “T HEN CATASTROPHE STRIKES :” READING DISASTER IN PAUL AUSTER ’S NOVELS AND AUTOBIOGRAPHIES « THEN CATASTROPHE STRIKES » : LIRE LE DÉSASTRE DANS L’ŒUVRE ROMANESQUE ET AUTOBIOGRAPHIQUE DE PAUL AUSTER Thèse en cotutelle présentée en vue de l’obtention du grade de Docteur de l’Université de Paris- Est, et de Doctor of Philosophy in Comparative Literature de Northwestern University, par Priyanka DESHMUKH Sous la direction de Mme le Professeur Isabelle ALFANDARY et de M. le Professeur Samuel WEBER Jury Mme Isabelle ALFANDARY , Professeur à l’Université Paris-3 Sorbonne Nouvelle (Directrice de thèse) Mme Sylvie BAUER , Professeur à l’Université Rennes-2 (Rapporteur) Mme Christine FROULA , Professeur à Northwestern University (Examinatrice) Mme Michal GINSBURG , Professeur à Northwestern University (Examinatrice) M. Jean-Paul ROCCHI , Professeur à l’Université Paris-Est (Examinateur) Mme Sophie VALLAS , Professeur à l’Université d’Aix-Marseille (Rapporteur) M. Samuel WEBER , Professeur à Northwestern University (Co-directeur de thèse) In memory of Matt Acknowledgements I wish I had a more gracious thank-you for: Mme Isabelle Alfandary , who, over the years has allowed me to experience untold academic privileges; whose constant and consistently nurturing presence, intellectual rigor, patience, enthusiasm and invaluable advice are the sine qua non of my growth and, as a consequence, of this work. M. Samuel Weber , whose intellectual generosity, patience and understanding are unparalleled, whose Paris Program in Critical Theory was critical in more ways than one, and without whose participation, the co-tutelle would have been impossible. -

Three Postmodern Detectives Teetering on the Brink of Madness

FACULTY OF EDUCATION AND BUSINESS STUDIES Department of Humanities Three Postmodern Detectives Teetering on the Brink of Madness in Paul Auster´s New York Trilogy A Comparison of the Detectives from a Postmodernist and an Autobiographical Perspective Björn Sondén 2020 Student thesis, Bachelor degree, 15 HE English(literature) Supervisor: Iulian Cananau Examiner: Marko Modiano Abstract • As the title suggests, this essay is a postmodern and autobiographical analysis of the three detectives in Paul Auster´s widely acclaimed 1987 novel The New York Trilogy. The focus of this study is centred on a comparison between the three detectives, but also on tracking when and why the detectives devolve into madness. Moreover, it links their descent into madness to the postmodern condition. In postmodernity with its’ incredulity toward Metanarratives’ lives are shaped by chance rather than by causality. In addition, the traditional reliable tools of analysis and reason widely associated with the well-known literary detectives in the era of enlightenment, such as Sherlock Holmes or Dupin, are of little use. All of this is also aggravated by an unforgiving and painful never- ending postmodern present that leaves the detectives with little chance to catch their breath, recover their balance or sanity while being overwhelmed by their disruptive postmodern objects. Consequently, the three detectives are essentially all humiliated and stripped bare of their professional and personal identities with catastrophic results. Hence, if the three detectives start out with a reasonable confidence in their own abilities, their investigations lead them with no exceptions to a point where they are unable to distinguish reality from their postmodern paranoia and madness. -

Authorial Turns: Sophie Calle, Paul Auster and the Quest for Identity

Authorial Turns: Sophie Calle, Paul Auster and the Quest for Identity © Anna Khimasia, 2007 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. Library and Bibliotheque et Archives Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de I'edition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-36802-2 Our file Notre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-36802-2 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non L'auteur a accorde une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library permettant a la Bibliotheque et Archives and Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par telecommunication ou par I'lnternet, preter, telecommunication or on the Internet,distribuer et vendre des theses partout dans loan, distribute and sell theses le monde, a des fins commerciales ou autres, worldwide, for commercial or non sur support microforme, papier, electronique commercial purposes, in microform, et/ou autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L'auteur conserve la propriete du droit d'auteur ownership and moral rights in et des droits moraux qui protege cette these. this thesis. Neither the thesis Ni la these ni des extraits substantiels de nor substantial extracts from it celle-ci ne doivent etre imprimes ou autrement may be printed or otherwise reproduits sans son autorisation. reproduced without the author's permission. In compliance with the Canadian Conformement a la loi canadienne Privacy Act some supporting sur la protection de la vie privee, forms may have been removed quelques formulaires secondaires from this thesis. -

In Search of Self: Explorations of Identity in the Work of Paul Auster

In Search of Self: Explorations of Identity in the Work of Paul Auster THESIS Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS in the Department of English at Rhodes University, Grahamstown, South Africa by Andrew Edward van der Vlies 1998 II ABSTRACT Paul Auster is regarded by some as an important novelist. He has, in a relatively short space of time, produced an intriguing body of work, which has attracted comparatively little critical attention. This study is based on the premise that Auster's art is the record of an entertaining, intelligent and utterly serious engagement with the possibilities of conceiving of the identity of an individual subject in the contemporary, late-twentieth century moment. This study, focussing on Auster's novels, but also considering selected poetry and critical prose, explores the representation of identity in his work. The short Foreword introduces Paul Auster and sketches in outline the concerns of the study. Chapter One explores the manner in which Auster's early (anti-),detective' fiction develops a concern with identity. It is suggested that Squeeze Play, Auster's pseudonymous 'hard-boiled' detective thriller, provided the author with a testing ground for his subsequent appropriation and subversion of the detective genre in The New York Trilogy. Through a close consideration of City of Glass, and an examination of elements in Ghosts, it is shown how the loss of the traditional detective's immunity, and the problematising of strategies which had previously guaranteed him access to interpretive and narrative closure, precipitates a collapse which initiates an interrogation of the nature and construction of ideas about individual identity.